|

Last Update:

Thursday November 22, 2018

|

| [Home] |

|

Volume 21 Issue 1 Pages 1 - 55 (July 2004) Citation: Carrillo-Rubio, E and Lafón, A. (2004) Neotropical River Otter Micro-Habitat Preference In West-Central Chihuahua, Mexico. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 21(1): 10 - 15 Neotropical River Otter Micro-Habitat Preference In West-Central Chihuahua, Mexico Eduardo Carrillo-Rubio1, Alberto Lafón2 1 Department of Natural Resources, Fernow Hall, Cornell

University, Ithaca, NY, 14853 USA,

e-mail: ec278@cornell.edu (received 24th June 2004, accepted 13th August 2004)

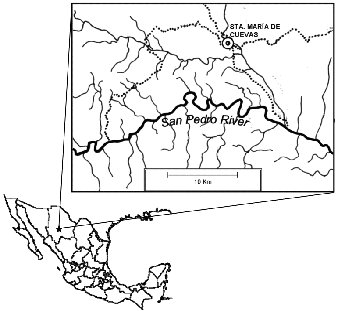

INTRODUCTION The Neotropical river otter (Lontra longicaudis) is currently listed as “Data Deficient” in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. This is because relatively little research effort has been devoted to the study of distribution and abundance of the species throughout its range, and detailed habitat and ecology information is lacking (MEDINA, 1999). In Mexico, the species is listed as endangered (SEMARNAT, 2002), and in the northern states it is estimated that populations are declining due to habitat deterioration (LIST et al., 1999). This represents a serious concern as, in the northernmost part of the distribution range of L. longicaudis (LARIVIÈRE, 1999), populations were never considered abundant (LEOPOLD, 1959). However, habitat preference studies, that assess the behavior of the animal and how they use their habitat, are essential as this information can be used to better comprehend the distribution, abundance, and needs of the species (see MORRISON et al., 1998). In order to describe L. longicaudis micro-habitat preference, we set out to: (1) characterise both used and available habitat; and (2) compare micro-habitat use in relation to availability. STUDY AREA Our study area was located in the west-central part of Chihuahua State in Northern Mexico. The San Pedro River is a mid-order perennial stream and the areas adjacent to the river are relatively undisturbed by humans. The topography is rugged and characterised by steep canyons with elevations ranging from 1650 to 1935 m. The mean annual temperature ranges from 15°C to 18°C and mean annual precipitation averages 500 mm. The riparian vegetation was dominated by an over-story of cottonwood (Populus spp.) and willow (Salix spp.) trees, whilst the surrounding highlands were covered by grasslands (Bouteloua spp.) and oak (Quercus spp.) woodlands. Livestock grazing is the main land use in the region, and fishing is practiced on a subsistence level by local communities.

METHODS We surveyed a 30 km stretch of the river for L. longicaudis sightings and use signs, such as spraints and latrines (SPÍNOLA and VAUGHAN, 1995; DUBUC et al., 1990; NEWMAN and GRIFFIN, 1994; MELQUIST and HORNOCKER, 1983, 1979). We then monitored used sites from June 1999 to October 2001 to investigate and describe habitat use patterns (CARRILLO-RUBIO, 2002). Locations of otter signs were used as the centre of our sampling sites. We measured the rock diameter where the sign was found, stream depth adjacent to the rock, and distance to the waterline (SPÍNOLA and VAUGHAN, 1995); average stream depth and width (GORDON et al., 1992); percent of under-story (>1 m), mid-story (1.0-1.5 m), and over-story (>1.5 m) vegetation using the step-point intercept method (HAYS et al., 1981); as well as distance to the riverbank, talus/rock, and vegetation cover. We randomly established sampling sites to assess available habitat characteristics (SPÍNOLA and VAUGHAN, 1995; STAUFFER and PETERSON, 1985a,b). Mean values and confidence intervals (C.I.) (HAYNES, 1982) were estimated to simplify our data, and the value of α=0.10 was established for all our calculations in order to reduce the probability of Type I error (STEIDL et al., 1997). We tested for micro-habitat characteristic differences between the used and random sites using the t test (HAYNES, 1982). To analyse habitat selection by the otter, all sites were classified into five pool categories using a pool rating system based on vegetation cover, average stream depth, and average stream width (HAMILTON and BERGERSEN, 1984 cited by CUPLIN, 1986). The Chi-square test (HAYNES, 1982; MARCUM and LOFTSGAARDEN, 1980) was performed in order to determine if each pool category was used in proportion to its availability. Finally, we determined otter preference for each pool category by obtaining a C.I. (97%) using the Bonferroni approach (MARCUM and LOFTSGAARDEN, 1980). RESULTS Differences between used (n=21) and random sites (n=25) were significant (P<0.10; Table 1). Habitat used by otters provided abundant and diverse escape cover when compared with random sites. The used sites were located in areas where large pools with average depths of 0.8 to 1.0 m (90% C.I.) and rock/talus cover within 4.8 to 8.1 m (90% C.I.) were present (Figure 2). Under-story vegetation cover in the used areas was abundant, ranging from 46 to 75 % (90% C.I.) and undisturbed by cattle grazing. Areas where under-story vegetation cover was severely affected by grazing were not used by otters.

Pool categories A and B were the deeper sections of the river with

the most abundant riverbank vegetation cover. Otters showed a preference

(97% C.I.) for pool categories A and B, using each more than in proportion

availability (Table 2). Pool category C, however, was used in proportion

to its availability, whilst categories D and E were avoided. DISCUSSION As reported elsewhere (e.g. SPINOLA and VAUGHAN, 1995), used sites by Neotropical otters (i.e. latrines, nests, rolling areas, holts, feeding sites) were located adjacent to, or within, large, deep pools that provided adequate escape cover. Our findings were also consistent with those reported for L. canadensis by MELQUIST and HORNOCKER (1983), and SPOWART and SAMSON (1986). We presume that the greater availability and diversity of prey species of fish expected to be found in deep pools (CUPLIN, 1986) is an important factor related to the otter’s consistent use of these particular habitat components, as noted also by MELQUIST and HORNOCKER (1983) for L. canadensis. No information regarding the availability of prey species for L. longicaudis was available for comparison with the pool characteristics identified in this study. Rock/talus cover adjacent to the riverbank was a characteristic of all the sites used. Talus cover is known to provide stable, year-long protection for reproduction and shelter for various wildlife species (COOPERRIDER, 1986). And the use of natural cavities, instead of excavating dens, is known to be common in L. canadensis (TESKY, 1993; and MELQUIST and HORNOCKER, 1983). However, we know of no previous information that has been published that analyses the relationship between this specific terrestrial feature and Neotropical otter presence. MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS Our results indicate that Neotropical otters preferred areas with specific habitat features that are dependant on isolation from human activities and healthy riparian vegetation structure. The presence of cattle discourages otter presence, and grazing destroys otter habitat through trampling and vegetation removal, which ultimately disrupts the regeneration process of plant species, including trees and shrubs. Even though we did not measure this variable directly, we were able to notice that during drought years and the low-water season, large pools become popular fishing spots and harassment, and sometimes death, of otters is common. Plans for in-situ conservation of river otters need to consider habitat connectivity and seclusion from human activities in order to provide suitable habitat, and provide educational outreach to local communities that depend on fishing for sustenance in order to reduce conflicts with otters. Acknowledgements - We would like to thank CONACyT, Sonia Nájera and the Mexican Affairs Office of the U.S. National Park Service for their support to carry out this project. Assistance provided by A. Loya and the Loya Family is always appreciated. REFERENCES Carrillo-Rubio, E. 2002. Uso y modelación del hábitat

de la nutria de río (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en el Bajo

Río San Pedro, Chihuahua. Unpublished MS thesis. Universidad Autónoma

de Chihuahua, Chihuahua, México. 80pp. Résumé:

Preference En Matiere De Micro-Habitat, Affichee Par La Loutre A

Longue Queue Dans Le Centre-Ouest Du Chihuahua, Au Mexique Resumen |

| [Copyright © 2006 - 2050 IUCN/SSC OSG] | [Home] | [Contact Us] |