|

IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Volume 26 Issue 2 Pages 65 -

131 (October 2009)

Citation: Polechla, P.J. Jr. and Carrillo-Rubio,

E. (2009). Historic and Current Distributions of River

Otters (Lontra canadensis) and (Lontra

longicaudis) in the

Río Grande or Río Bravo del Norte Drainage of

Colorado and New Mexico, USA and of Chihuahua, Mexico and Adjacent

Areas. IUCN

Otter Spec. Group Bull. 26 (2): 82 – 96

Previous | Contents | Next

Historic and Current Distributions

of River Otters (Lontra canadensis) and (Lontra longicaudis)

in the Río Grande or Río Bravo del Norte Drainage

of Colorado and New Mexico, USA and of Chihuahua, Mexico and

Adjacent Areas

Paul J. Polechla Jr.1 and

Eduardo Carrillo-Rubio2,

1Department

of Biology, MSC03 2020, 1 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque,

NM 87131-0001 USA. E-mail:ppolechl@sevilleta.unm.edu

1Department of Natural

Resources, Fernow Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 USA |

|

|

Abstract: The Río

Grande drainage is an important and imperiled wetland of the

US/Mexican border arid lands. There is a desire to restore otter

populations in this river by interested parties. In order to

follow IUCN guidelines for restoration, biologists need learn

more fully the situation prior to implementation of restoration

management. A prerequisite for proper restoration conservation

is to know the organism’s taxonomy (i.e., what taxa or

species and subspecies one is dealing with), distribution, and

relative abundance. The historic and current distribution of

the Nearctic otter (Lontra canadensis) and

Neotropical otter (L. longicaudis) in the borderlands

of US and Mexico are reviewed in this paper. The evidence indicates

that otters were native to the Río Grande valley and has

been recorded in the languages and customs of Native Americans

such as the Pueblo people prior to European settlement of the

area. The first Spanish documents we were able to find whereby

otters were recorded, date to the middle 16th century. Otters

during historical times were probably more numerous than previously

thought and one of the first wildlife laws in the borderlands

revolved around a moratorium on trapping the otter and beaver.

Presently, populations of otters occur in 1) the Río San

Pedro of Chihuahua, a tributary of the Río Conchos entering

the Río Grande from the southeast, 2) the upper Río

Grande near the Colorado/New Mexico border, and 3) the middle

Pecos River in southeastern New Mexico entering the Río

Grande from the west. These observations are corroborated

by multiple observations by competent observers and in the case

of the first population, otter photos and sign. These populations

are centered on areas with macro-habitats characterized by a

river flowing through 1) deep canyons, or 2) ancillary wetlands.

Considerable more detailed survey work is needed to determine

the full extent of the distribution of otters in the Río

Grande drainage. A genetic study is critically needed to determine

the true taxonomic affiliation of these recently discovered populations.

A moratorium on translocations should be put in place for the

Río Grande to conserve the native populations already

existing. |

| Keywords:

Nearctic, Neotropical, river otter, Río Grande, Río

Bravo del Norte, Pecos River, Río Conchos, distribution,

historic, current, USA, Mexico, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas,

Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, Tamaulipas, Spanish, Native

American, Pueblo, habitat, beaver, translocation, stocking, IUCN,

moratorium, genetics. |

| Française | Español |

INTRODUCTION

In his later years when asked by a reporter about rumors of his death,

Samuel Clements or Mark Twain was quoted as saying (Paine

1912): “Just

say the report of my death has been grossly exaggerated.” The

same could be said about the river otter of the Río Grande or

Río Bravo del Norte except for one important distinction; Mark

Twain was a well-known author of the literary world, whereas the river

otter of the Río Grande is a veritably unknown animal in the

scientific world.

Various authors reviewing the mammalian species of a given geopolitical

area (i.e. country or state) have often neglected the otter. Granted,

writing the “mammals of” type book requires much diligence

to include detailed information such as the distribution for a specific

geopolitical area. This is especially true of areas like the borderlands

of the US and Mexico where there are extremes in altitude and climate

that produce a high floral and faunal diversity. The initial thought

of an otter, a semi-aquatic mammal, totally reliant on the close proximity

to open water, in the midst of a desert seems to be an enigma. Wildlife

biologists in the arid southwestern US and northern Mexico usually

study the desert, grassland, or alpine fauna. Be that as it

may, ignoring a semi-aquatic member of the native fauna of the priceless

wetlands of a sun-parched region is totally irresponsible. Add to the

difficulty of developing an accurate faunal list with the many languages

and cultures (e.g., English, Spanish, Diné, Pueblo, etc.) in

the region, plus the fact that a boundary bordering two countries (USA

and Mexico) and six states (New Mexico, Texas, Chihuahua, Coahuila,

Nuevo Leon, and Tamaulipas) is a river with tributaries on both sides

and this is a challenging situation prone to developing errors of omission.

Mark Twain is also credited for saying “Whiskey is for drinkin’;

water is for fightin’.” It surely applies to the endangered

waters of the American West. The Río Grande headwaters

in southern Colorado and then flows through the San Luis Valley, the

Taos Plateau of New Mexico, the middle Río Grande valley of

New Mexico, the Mesilla Valley, and the lower Río Grande and

along the Texas/Mexican border then out to the Gulf of Mexico between

the neighboring cities of Brownsville, Texas and Matamoros, Tamaulipas.

The Río Grande ranks as the longest river in Mexico, the eighth

longest in the US (US Geological Survey web site), ninth longest in

North America (with 52.1% in the USA and 47.9% in Mexico), and the

26th longest in the world (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_rivers_by_length visited

on 3 December 2007) with 3,057 km of waterways. The Río

Grande with all its drainages (e.g., Pecos River) ranks as the third

largest river system in the US and measures an estimated 4,386-4,547

km long.

In 1997 the US Environmental Protection Agency declared the Río

Grande to be an American Heritage River to further “natural resource

and environmental protection” (Clinton. 1997). Sections of the

river (and the tributaries including the Red River, Río Chama,

East Fork of the Jemez River, and Pecos River) in northern New Mexico

and west Texas have been classified as “Wild and Scenic Rivers” by

the federal government. American Rivers, a non-profit river advocacy

organization, ironically has declared the Río Grande and its

tributaries the Río Chama and the Santa Fe River, one of the

most threatened or endangered rivers in the US, eight times from the

period 1986-2007 (American Rivers, 2007). Furthermore in 1993, the

Río Grande topped the charts and in 2007 the Santa Fe River

was listed as the most endangered. The Santa Fe River is now a dry

ditch but once was a natural flowing stream in 1881. The Río

Costilla, a tributary on the east bank on the Colorado/New Mexico border,

is also dry most of the year (Polechla, 2000). The Río Grande

is truly endangered too since it only occasionally (e.g., 2000, 2001,

and 2006) reaches the Gulf of Mexico like it formerly did. Reasons

cited for its poor condition include intensive agriculture, overgrazing,

plus improper disposal of toxins, industrial pollution, domestic sewage,

and mine wastes. The Environmental Protection Agency

(2000) had proposed

a molybdenum mine on the Red River near Questa, NM as a “Superfund

Site” for cleanup of mine tailings. By far, the largest threat

to the Río Grande remains dewaterization.

New Mexico is the last state in the US to restore river otter populations

(Anonymous 2006). Since river otters in the Río Grande are regarded

as rare and their riverine habitat is also very endangered, this publication

summarizing the current situation with the river otter in the Río

Grande is very timely. This article is an attempt to correct this lack

of attention devoted to the river otter in this drainage. We will take

a historical as well as a contemporary examination of the evidence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We searched for records in English and Spanish at: 1) the special

collections at Center for Southwestern Research (CSWR) at the Zimmerman

Library at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, 2) City of

Chihuahua Archives, CHIHUAHUA, México, and 3) antique maps at

the Map and Geographic Information Center (MAGIC) at the Centennial

Science and Engineering Library (CSEL), University of New Mexico for

place names with otters, and 4) books written on regional fauna of

the borderlands. Wherever possible, we read original primary sources.

We also surveyed sections of the Río Grande and its tributaries

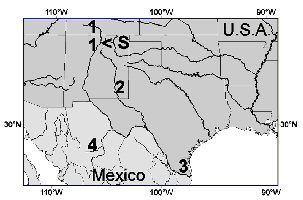

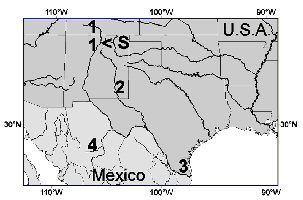

ourselves (Figure 1). While conducting reconnaissance trips we interviewed

local people along the river and its tributaries about otters.

|

| Figure

1. Spatial distribution of recent records of native river

otters (possibly Lontra canadensis lataxina) in the Rio Grande

watershed (upper Rio Grande =1; middle Pecos river =2; lower

Rio Grande Valley =3; upper Rio Conchos =4) and stocked populations

of the exotic L. c. pacifica subspecies in the Rio Pueblo de

Taos at > (S). (click for larger version) |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

USA

Colorado

American Period

Otters are known historically from the so-called San Luis Valley

or the upper Río Grande on the present-day New Mexico/Colorado

border (Coues, 1898). American explorers, such

as the phonetic speller Major Jacob Fowler trapped “bever” [sic

= beaver (Castor

canadensis)] and “aughter” [sic = otter] in 1822 in

the upper Río Grande drainage of present day Colorado. He was

an unusual trapper since he was educated enough to record his daily

catch in a journal and use a sextant and compass to pinpoint his location

all while enduring the rigors of outdoor life.

Twenty-first Century

At the southern part of Alamosa National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), two wildlife

biologists, Kelli Stone and Kristina Crowder, made an interesting observation

while driving to check their mist nets. Kelli had been apart of the Green River,

Utah otter translocation program (she had seen adults and young at Ouray National

Wildlife Refuge, near Green River, Utah, and in a northern Rocky Mountain stream

as well). On 12 September 2001 at about 0630 Mountain Standard Time (MST),

both Kelli and Kristina saw an otter running across a sand bar close to the

far bank of the Río Grande (river width = 18.3 m) above La Jara Creek,

Alamosa County, Colorado. (mentioned briefly in Polechla

2002b, and recorded

fully in the field notes of Paul Polechla, 28 February 2002). It appeared “long,

thin, and dark” with its head and body about 76.2 – 91.4 cm long.

They saw the animal at a distance of 27.4 m for about 3-5 s duration. It had “an

S-shaped crimp” in it’s back displaying an up and down motion.

After there initial observations, it bounded onto the willow bank. It did not

resemble a mink (Neovison vison), weasel (Mustela frenata),

muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus), or beaver in size, shape, and movement.

One of Kelli and Kristina’s colleagues also saw one otter at 1900 MST

at the same site. We regard their sightings as highly credible ones due to

the precision and accuracy of their descriptions of the morphology and behavior

of animal they saw and the match with those of the river otter.

To date, no translocations of otters have been conducted into the Río

Grande (Polechla, 2002a). However, translocations of exotic otter subspecies

were placed in the Piedra River, Dolores River, Gunnison River at Black Canyon,

and headwaters of the Colorado River in Rocky Mountain National Park; all are

apart of the Colorado River drainage. Otters were also translocated to Cheesman

Reservoir along the South Platte (Polechla, 2002a,b; DePue

and Schnurr, 2004)

part of the Missouri/Mississippi River drainage.

Beaver and muskrat both occur at ANWR (Polechla, unpublished data)

and south into New Mexico (Polechla, 2000). Besides the river the

area has a myriad of abundant wetlands including: wet meadows, marshes,

oxbows, sloughs, canals, and small reservoirs.

New Mexico

Native American Period-Pre/Early European Contact

A photo in Dozier (1983) documents Santa Clara

Pueblo men wearing otter fur in braids in their hair. Hill

(1982) tells

of people from Santa Clara Pueblo wearing otter fur headbands and

collars. Bailey (1931) described the Native American knowledge about

the otter along the Río Grande. “The Taos Indians are

familiar with them, and bits of fur were seen on their clothing and

ornaments as well…” He added that the Taos Pueblo people

not only utilized their skins but also had a unique name in their

Tewa language for the otter. An otter effigy pot was excavated from

Pecos Pueblo on Arroyo del Pueblo, a tributary of Glorieta Creek,

a tributary of the upper Pecos River located about 4 km South and

0.8 km East of the village of Pecos, New Mexico (Polechla

2000, Kidder

1932). This site was estimated to be between 1200 and 1838 AD.

Spanish Colonial Period

In 1541, Hernando de Alvarado commented that the “Río Pecos” or

Pecos River “contains very good trout and otters” (Hodge,

1946).

Nicolas de Lafora (Weber, 1971) wrote about the Río Grande in 1767 commenting

that New Mexicans “pay no attention to otter, beaver, ermines, and martin

[sic marten] skins, which they have in abundance, because they do not know their

value.” Fray Morfi (1782 fide Rea 1947) records beaver and otter on the

Río Grande in 1782.

The place called “Las Nutrias” along the “Camino Real” was

named in Spanish after ‘the otters’ and dates back to 1682 (Rivera

and Humboldt, 1807; Julyan, 1998, Polechla,

2000; LoPopolo, 2006; Carlos LoPopolo,

personal communication). This village is located at 34.477 degrees N.106.770

degrees West Longitude on the east bank of the Río Grande in present-day

Socorro County, NM.

There are a number of other place names with nutrias or otters for localities

in New Mexico (Pearce, 1965; Julyan,

1998; Topozone.com) and Colorado (Polechla,

2002a). Often times place names with otter or nutria refer to an abundance

of otters in this region historically (Polechla, 2002c).

The officials in City of Chihuahua, fearing over-trapping of beaver and otter

in the Río Grande, closed the river to trapping these two species (Weber,

1971) publishing the declaration in the official newspaper “El Noticioso

de Chihuahua” in 1838 (Polechla et al., in

prep). This indicates a greater

original abundance than was previously thought by authors such as Bailey

(1931) and Findley et al. (1975).

Early American Period

The military expedition known as the “Army of the West” led

by Lieutenant Colonel W. H. Emory guarded the Mormon Battalion from

Fort Leavenworth, Kansas to San Diego in present day California (Emory,

1848). They came via the Santa Fe Trail’s Mountain Route, passed

from later-day Raton to Santa Fe, NM then to the Río Grande

(on a main trail called the Camino Real) as far south as the Fra Cristobal

Mountains and then exited the Río Grande valley west across

the mountain gap now known as Emory Pass (Julyan,

1998), present-day

NM. On 11 October 1846, Captain A. R. Johnston of the expedition wrote

the following about the east bank of Río Del Norte at the base

of Fra Cristobal Mountains (Emory, 1848). “In passing the river,

I saw the tracks of the otter, the catamount, the wildcat, the bear,

the raccoon, the crane, the duck, the plover, the deer, and the California

[sic probably Gambel’s] quail.” Emory, the namesake of

the Emory oak (Quercus emoryi), summarized the observations

of others in the Mormon Battalion expedition by writing “…for

here we saw for the first time in New Mexico, any considerable “ signs” of

game in the tracks of the bear, the deer, and the beaver. We flushed

several bevies of the blue quail, saw a flock of wild geese, summer

ducks, the avocet, and crows.” It must be noted that the area

north of this region along the “Camino Real” contained

numerous human settlements, which had over harvested the wildlife along

the Río Grande. Just north of Tome, Johnston wrote about the

otter’s commensal partner, the beaver. “Above this camp,

there is on the river a considerable growth of cotton-wood, among which

are found some ‘signs’ of beaver.”

Other observations are known from the upper Río Grande. A “Mr.

Dowell” said that otter were found near the junction of the El

Rito de los Frijoles and the Río Grande between 1910-1911 (Henderson

and Harrington, 1914). The junction of these two waters lies

within present-day Bandelier National Monument, Sandoval County,

NM. Bailey

(1931) cited otter records from the upper Río Grande on the

following localities: “near Espanola, Rinconada, and Cienequilla.” “Cienequilla” or “Cieneguilla”,

meaning small marsh in Spanish, is now known as Pilar, Taos County,

NM (Julyan, 1998).

Bailey (1931) readily admits the conundrum

of not having specimens to properly decide which taxa he is dealing. Writing

about trappers' records of the 1820’s for the Gila River of southwestern

New Mexico in the Colorado River basin he says. “These records

undoubtedly refer to the typical Arizona form [L c. sonora],

but no more records are available in New Mexico except for the upper

Río

Grande and Canadian Rivers in the northeastern part of the state, where

the species is probably different. There is, however, not a specimen

from the State available for study and comparison, and until specimens

are obtained, no definite decision can be arrived at in regard to the

subspecies.” Findley et al. (1975) merely cites Bailey

(1931) and the record of McClellan

(1954) in the Gila River (1 mile [1.6 km]

S Cliff, Grant County) and adds “the species may well be extinct

in the state.” Findley et al. (1975) do

not indicate if any effort was made to survey for otters. They do not

hazard a guess as to what subspecies might be in the Río Grande

or Colorado, or Canadian River drainages of the state.

Modern Period

San Luis Valley

In the 1970’s, Dean Swift saw three to four otters at Eastdale

Reservoir (part of the Río Costilla drainage which winds its

way across the Colorado/New Mexico border and flows into the Río

Grande’s east bank (Polechla, 2000)).

At the mouth of the Río

Costilla, Jim and Peggy Swayback of MacKintosh, NM saw an otter (Polechla,

2000).

Taos Gorge

Dan Wood and Richard Spiegel of Bureau of Land Management (BLM)

were rafting the Río Grande when they saw an otter about 11.7

km S of the Colorado/New Mexico state line (Stahlecker

1986). Doug

Scott Murphy, a pioneer river outfitter on the upper Río Grande

and artist, claims to have seen a river otter at “Razorblades” about

3.2 km upstream of Sheep’s Crossing in 1997 (Polechla,

2000).

Todd Bates who lives on the Río Fernando de Taos (a tributary

on the Río Grande’s east bank) claims to have seen an

otter at the Sunshine Valley section of the Río Grande (Polechla,

2000).

Red River

Red River is a tributary on the east bank of the upper Río

Grande in New Mexico. A New Mexico Environmental Improvement Division

employee on the Red River at Columbine Canyon believed they saw

an otter in 1999 (Polechla, 2000).

Pecos River

Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge (BLNWR), Chaves County,

New Mexico lies on the Pecos River and has been a locality for

several otter observations (Polechla,

in prep. and 2002b, not

cited by Anonymous, 2006). The refuge is

characterized by a myriad of different wetlands next to the river

including: springs seeps, oxbow lakes, marshes, saline lakes,

karst sinkholes, shallow reservoirs, and canals.

The US Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service reported

some sightings at BLNWR (Polechla

2002b). One of their

reports (USDI F&WS 1994) states the following. “A

river otter (Lutra [=Lontra] canadensis)

was reported by a visitor on Unit 6 reservoir in early May [1994].

An otter has never been documented on the refuge, and seems highly

unlikely. However, William R. Radke (refuge manager) found mammal

prints along the Pecos River in October 1993, which he believed

to possibly belong to a river otter. In addition, a fire crew dispatched

from Washington State to aid the refuge during the summer fire

season reported seeing a river otter at Unit 15 reservoir. None

of these sightings were ever confirmed.” On 25 April 1999,

Judy Dane, a volunteer coordinator with the New Mexico Museum

of Natural History saw what she believes to have been an otter

on the N end of Unit 6 impoundment of BLNWR (Radke,

1999, Judy

Dane personal communication to Paul Polechla, 22 June 2004).

This location is on the west side of the refuge and is close

to the Pecos River. Judy is a long time birder and has seen lots

of different species of wildlife on ecotours. She was standing

on the road bird watching in the late afternoon when at a distance

of 91.4 – 183 m, with the aid of her binoculars; she caught

a quick glimpse of an otter. By the “dark color, long dark

tail, size, and way it ran…humping its back and not waddling” she

assured me it was a river otter and contends it was not a muskrat

or a beaver. It was “bounding the weeds at the edge of

the water”. Furthermore she says, “I’ve

seen sea and river otters in Alaska... and beaver and muskrat

in New Mexico and the Eastern US” Her description/observation

is consistent with otter appearance and behavior and seems very

credible. Shy of an actual photo or track cast, etc. this observation

demonstrates the occurrence of river otter here.

Texas

Since the early province of Chihuahua included some of present

day west Texas along the Río Grande, the above-mentioned decree

in the 1838 “El

Noticioso de Chihuahua” also places otter in this part of the state (Polechla

et al., in prep). In their “Mammals of North America”, Hall

and Kelson (1959) do not have a Texas Río Grande location but do

provide a central Texas distribution record on the Colorado River near Austin,

citing

Bailey, 1905. In the next addition of “Mammals of North America”,

Hall (1981) shows the Brownsville, Cameron County, Texas location. This is

based on an actual otter specimen that Van Zyll de Jong (1972) listed and measured

and statically compared to other Lontra specimens including L.

canadensis and L. longicaudis. Van Zyll de Jong identified the

specimen as L. canadensis lataxina. Brownsville lies at the mouth

of the Río Grande across the river from Matamoras, Tamaulipas, Mexico. Davis

and Schmidly (1994) also showed the Río Grande locality but provided

no further information. Earlier versions of this work (Davis

1966, 1974) do

not show this locality. Polechla (1988, 1990) cites Hall

(1981) and Polechla

(1990) adds the rest of the Río Grande based on Weber

(1971). Polechla

(2000, 2002b) and Gallo (1986, 1989) cite this distribution locality in Cameron

County, along the Río Grande (plus one at the mouth of Colorado River).

Mexico

Harris (1968, p. 212) lists the type locality of the

Neotropical otter of México (Lontra longicaudis annectens) Major,

1897 as Terro Tepic, Río de Tepic, Nayarit, Mexico and shows the

trans-Madrean distribution making a slight “U” shape along

the Pacific coast from the Sierra Madre del Sur to a point about even

on the Mexican mainland with the tip of Baja California and on the

Atlantic side of the Gulf of Mexico to Tamaulipas, Mexico (including

an unnamed coastal river). Harris (1968) does not mention the Río

Grande nor is it mapped for distribution for the Nearctic otter of

the Southeastern US (L. c. texensis (now a synonym for L.

c. lataxina)). New Mexico is listed as part of range of L.

c. sonora and the upper part of Río Grande, Pecos, and

Arkansas Rivers (in state of Colorado) shown on the distribution map.

No individual records are shown on any of Harris’s maps however.

Chihuahua

The aforementioned decree in the 1838 “El Noticioso” for

Chihuahua closing the Río Grande to trapping beaver and otter

constitutes one of the first wildlife laws in the state of Chihuahua

(Polechla et al., in prep). Now otter populations are known from other

parts of the Río Grande drainage and western Chihuahua near

the border with Sonora and Sinaloa.

“West”-Central Chihuahua- Río San Pedro,

Río Conchos-Río Bravo Del Norte/Río Grande Drainage.

This region lies on the eastern slope of the Sierra Madre Occidental

of Mexico and has only been recently examined for otters. Carrillo-Rubio

and Lafón

(2004) published on the habitat of the otter in west-central Chihuahua, Mexico.

They found otter scats and tracks plus even took a photograph that the second

author (ECR) showed in a slide show at the 2004 IUCN Otter Specialist Group Colloquium

(Carrillo-Rubio et al., 2004). They emphasized the microhabitat

selection characterizing both the occupied and available habitat. Although this

is an essential aspect of otter biology and conservation, there was an even greater

significance of their work that was not mentioned. They had found otters where

no other scientist had reported them before! Gallo (1986, 1989), Lariviere

(1999), and even Gallo

and Casariego (2005) do not show the west-central Chihuahuan population

just the Chihuahuan/Sonoran border population described in detail in the next

section. The previous population that other biologists had described was in extreme

western Chihuahua near the Sonoran border on the west side of the Continental

Divide running down the Sierra Madre Occidental. The population in west-central

Chihuahua is totally new to science. Furthermore to date, this “new” population

is 1) the only one on the east side of the Sierra Madre Occidental, 2) the eastern

most population in Chihuahua, and 3) the northeastern most otter (Lontra spp.)

population in México.

Not only that but, the species of river otter (Lontra sp.) that they

are actually dealing with is not well understood. Recall that the arid US/Mexico

borderlands are the regions where both the Nearctic otter of the north meets

the Neotropical otter of the south. Prior to translocations (of different subspecies

from other drainages) by the US states of Colorado, Arizona, and Utah, only the

southwestern subspecies of the Nearctic river otter (L. canadensis sonora)

occurred in the Colorado River (Polechla and Walker

2008). When Bailey (1931) wrote his “Mammals of New Mexico”, he summarized a few reports of

otters on the Río Grande. It is unknown whether he searched for them himself,

but he probably was occupied investigating the diversity of mammals since the

state ranks very high in diversity ranking with California and Texas (Caire

1978).

The situation is further complicated since he did not have a specimen from the

state but knew full well that they have long been a part of the native fauna.

Without a specimen and knowing that the next drainage to the arid west was the

Colorado River, he assigned the otters in the entire state; including the Gila,

San Francisco, and San Juan River drainages, plus the Río Grande drainage,

and the Canadian River drainages, to that of the southwestern subspecies based

on geographical proximity.

Carrillo-Rubio and Lafon (2004) and Carrillo-Rubio

et al. (2004) working in Mexico

where the most-abundant otter is the Neotropical otter, assumed that the otter

in Chihuahua must be the Neotropical otter. They were not aware of L. canadensis

lataxina from the mouth of the Rio Grande at Brownsville, Texa that Van

Zyll de Jong (1972) examined and identified. Since they worked in the Río

San Pedro, which flows into the Río Conchos a tributary of the Río

Grande, this might not be the case. Since both Carrillo-Rubio and his associates

and Bailey knew of otters in the Río Grande but had no skin/skull specimens

to examine for identifying characteristics (Polechla,

Gallo, Tovar 1987), the

true identity awaits further study to determine if it is the Nearctic, Neotropical,

or an undescribed species or subspecies. Much study is needed to learn about

this newly discovered population. It should be conserved at all costs.

Chihuahua/Sonora/ Sinaloa Border

This area of Mexico is on the western slope of the Sierra Madre Occidental and

drains into the Sea of Cortez (i.e. Gulf of California) and ultimately into

the Pacific Ocean. Indigenous people are well aware of the Neotropical

otter of this region. The Tarahumara and northern Tepehuan people in the Río

Verde and Río Mayo of Chihuahua were familiar with the otter, using

their meat for food, fat for folk medicine, and skin for a sleeping mat (Sturtevant,

1983).

In 1904, Carl Lumholtz’s (1973) discovered “tracks of many raccoons

and otters…” along the Barranca de San Carlos that drains into the

Río Fuerte west of Nogal, Sinaloa, Mexico. Since Lumholtz’ observations,

the distribution of the Neotropical otter known to science has been moving northward

along the west side of the Sierra Madre Occidental. This is largely attributed

to an increase in mammalogical studies in northern Mexico associated with specimens,

photographs, and sightings of otters.

Leopold (1959) provides records on the Río Gavilán. Cockrum

(1964) reported on a specimen trapped from the Río Mayo near San Bernardo, in

southeastern Sonora in spring of 1963. Anderson (1972) cited two specimens from

northwestern Chihuahua from the Río Tutuaca, 20 km S Yaguarachie. In the

same general region of the state of Chihuahua, Anderson (1972) also gives records

for the Río Papigohi about 40 km down river from Temosahi. Roth

and Cockrum (1976) reported on a specimen from the Río Mayo at Alamos from 1965 plus

further to the north, another one at Los Pilares, 7 miles E [= 11.3 Km] of Yecora,

on the Río Mulatos, a tributary of the Río Yaqui. Caire

(1978) cites Roth and Cockrum (1976) and Anderson

(1972) and states that native people

at Tres Ríos on the Río Negro told him “that otters have

occurred there occasionally”. Brown et al. (1982) photographed three otters

in the Río Yaqui, Sonora about 3 km downstream of the Río Chico

confluence. The Río Yaqui flows into the Gulf of California between Guaymas

and Ciudad Obregon, Sonora, Mexico.

Along the Río Bavispe east of Tres Ríos Mesa in the Sierra Occidental

in Chihuahua, Johnson (2005) cites a Brian [Long] and Alan [last name unknown]

searching for otters. Johnson is probably referring to the reconnaissance trip

planned by Brian Long (2001, personal communication, 2001) of which no published

reports have been produced from this trip. To date, this region may constitute

the northern-most distribution of the Neotropical otter but lies on the west

side of the Continental Divide and is not in the Río Grande drainage.

Coahuila/Nuevo Leon/Tamaulipas Border

Río Salado

These river headwaters on the eastern side of the Sierra Madre Oriental

flow into the Río Grande on the Mexican side. The Río

Salado, a Río Grande tributary in eastern Coahuila, northern

Nuevo Leon, and northern Tamaulipas remains unsurveyed for otter, although Villa (1954) surveyed the river for beaver only. Bernal

(1978) later

surveyed beaver in this drainage in the state of Nuevo Leon.

Tamaulipas

The rivers in this region south of the mouth of the Río Grande,

headwaters on the eastern side of the Sierra Madre Oriental and flow

(albeit now irregularly) directly into the Gulf of Mexico and finally

into the Atlantic Ocean. Gallo-Reynoso

(1997) gave the following record in his review of Neotropical otter in Mexico. “Río

El Salado, afluente del Río Conchos, 2 km O de Paso Hondo (Mpio. De San

Fernándo, 50 m). Se revisó la piel de un individuo macho. Este

registro constituye el más norteño de la nutria neotropical en

la vertiente del Golfo de México (N).” This is translated as follows. “The

river ‘El Salado’, a tributary of the ‘Río Conchos,

2 km west of Paso Hondo (Municipality of San Fernado, 50 m)’. I examined

the pelt of an individual male. This constitutes the most northern record of

the Neotropical otter on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico.” This location

is about 425 km south of the mouth of the Río Grande.

CONCLUSION

In 1541, Spanish explorer Hernando de Alvarado is credited as the

first person to observe otters in the Río Grande drainage and

to write about his observation. Native American tribal knowledge of

otters probably predates the Spanish record. Analysis of the early

historical documents indicates that otters have been recorded in the

Río Grande from the 16th through the 21st centuries. One archaeological

record for an otter effigy pot was found in deposits dated from the

13th to the 19th centuries. Like the Arkansas (Polechla,

1987) and

the Colorado (Polechla, 2002b) Rivers, the historical distribution

of otters was from the headwaters to the mouth.

Unregulated fur trapping on Río Grande beavers and otters began

in earnest in the Mexican Period and continued through the American

Period. Undeniably there are at least three localities in the Río

Grande where otters are currently known to occur (Figure

1): 1) the

Río San Pedro in Chihuahua 2) in the upper Río Grande

around ANWR near the New Mexican border, and 3) the Pecos River at

BLNWR. Reports have come from competent biologists and naturalists

with previous experience with otters. At this time, the most extensive

population seems to be located in the Río San Pedro in Chihuahua

that is about 106.9 km from the closest population near the Chihuahuan/Sonoran

border on the other side of the Continental Divide. The habitat of

the first locality is where a river passes through a deep canyon and

the second and third localities are situations in which rivers flow

by small reservoirs, ponds, oxbow lakes, and springs. The deep canyons

might restrict some human visitation and development. Having a number

of wetlands juxtapositioned near each other is ideal for otter foraging

and traveling behavior. Very little of the Río Grande drainage

has been sufficiently examined however, with only 292.8 km to date

(Polechla, 2000; Carrillo-Rubio

and Lafón, 2004; Polechla, unpubl.

data), representing only 6.4-6.6 % of the total km of river ways in

the Río Grande drainage. The newest discovery of otters in the

Río Conchos necessitates that examination of the other tributaries

as well as the Río Grande per se, must be surveyed. The specific

designation of these otter populations, let alone the subspecific designation,

are unclear and await further study.

Management Implications and Recommendations

Mark Twain’s famous pun is applicable (Gore,

2006). “Denial

ain’t just a river in Egypt.” Contrary to the prevailing

opinion, native populations of river otters are present in the Río

Grande drainage. Governmental agencies denial of this fact and refusal

to protect them needs to be corrected. Currently, five river otters

(L. c. pacifica) from the state of Washington were unscientifically

stocked (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 2008) into a river drainage that

undeniably already has a native otter. The “New Mexico

Friends of the River Otters”, the group responsible for the action,

has plans to stock more foreign Washington (Seattle

Post-Intelligencer, 2008) and Oregon (Associated

Press, 2007) otters into New Mexico. This

threatens an existing native population of river otters, currently

imperiled. The five stocked otters need to be live-captured and returned

to Washington. A genetic study is needed to elucidate the taxonomic

relationship of the otters of the US/Mexico border. Experienced otter

trackers need to conduct additional surveys to determine the distribution

of otters of the Rio Grande and borderland region in general (e.g.

Colorado River drainage to the west and the Canadian River drainage

to the east).

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS: We would like to

thank the following agencies for their support: Colorado Ocean Journey,

BLM, Theodore Roosevelt Fund, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Map and

Geographic Information Center, and the Center for Southwest Research.

Special thanks goes to Nancy Brown-Martinez and Mary Wyant for their

expertise.

REFERENCES

American

Rivers. (2007). America’s most endangered

rivers. 2007. American Rivers, USA.

Available from: http://www.americanrivers.org/[accessed August

2008]

Anderson,

S. (1972). Mammals of Chihuahua,

Mexico, taxonomy and distribution. Bull. Am. Mus.

Nat. Hist. 148: 151-410.

Anonymous. (2006) (24 July). Feasibility study: potential

for restoration of river otters in New Mexico. New Mexico Department

of Game and Fish, Santa Fe, NM, 59 pp.

Associated Press. (2007).

State to reintroduce river otters next year. 21 November.

Bailey,

V. (1905).

Biological survey of Texas. North American Fauna. 25: 1-222.

Bailey,

V. (1931).

Mammals of New Mexico. North American Fauna. 53: 1-412.

Bernal, J.A. (1978).

Estado actual del castor Castor

canadensis mexicanus V. Bailey 1913, en el estado de Nuevo Leon,

Mexico. Thesis professional Universidad de Autónoma de Nuevo

León, Monterrey, NL, 75pp.

Brown, B.T., Warren,

P.L., Anderson, L.S. and Gori. D.F. (1982).

A record of the southern river otter, Lutra longicaudis, from

the Río Yaqui, Sonora, Mexico. J. Arizona-Nevada

Acad. Sci.

17: 27-28.

Carrillo-Rubio,

E. and Lafón.

A. (2004). Neotropical

river otter microhabitat preference in west-central Chihuahua, Mexico.

IUCN OSG Bull. 21:

10-15.

Carrillo-Rubio

E., Lafón,

A., Mendoza, A.J. and Anchondo, A. (2004). Ecological classification

of otter habitat using presence/absence data. [abstract] IXth

International Otter Colloquium: Otters: Ambassadors for Aquatic Conservation. June

4-10, 2004. Abstracts. Frostburg State University, Frostburg, MD.

Caire, W. (1978). The

distribution and zoogeography of the mammals of Sonora, Mexico. Ph.D.

Dissertation, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM. 613 pp.

Clinton,

W.J. (1997). September 11,

Executive Order 13061. 62(178), 48443-48448.

Cochrum, E.L. (1964).

Southern river otter Lutra

annectens from Sonora, Mexico. J. Mammal. 45: 634-635.

Coues, E. (ed.)

(1898). The journal of Jacob Fowler, narrating an adventure from Arkansas through

the Indian Territory, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico to

the sources of the Río

Grande del Norte, 1821-22. F.P. Harper, New York, NY. 183 pp.

Davis, W.B. (1966). The mammals of Texas. Texas

Parks and Wildlife Department, Austin, TX 267 pp.

Davis, W.B. (1974).

(2nd edition) The mammals of Texas. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department,

Austin, TX 294 pp.

Davis,

W.B. and Schmidly, D.J. (1994). The mammals of Texas.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Austin, TX. 338 pp.

DePue, J.E. and

Schnurr, P. (2004). Status of Colorado’s

river otter reintroductions: looking good! [abstract] IXth

International Otter Colloquium: Otters: Ambassadors for Aquatic Conservation.

June 4-10, 2004. Abstracts. Frostburg State University, Frostburg,

MD.

Dozier, E.P. (1983).

The Pueblo Indians of North America. Waveland Press, Prospect Heights,

IL, 224 pp.

Emory, W.H. (1848). Notes of a military reconnaissance from Fort Leavenworth, in Missouri

to San Diego, in California, including part of the Arkansas, Del Norte,

and Gila Rivers. Wendell and Van Benthuysen, Washington, D.C., 737

pp.

Environmental Protection

Agency. (2000) (11 May). NPL Site Narrative for Molycorp, Inc., Questa, NM. Federal

Register. 65:30489-30495.

Findley, J.S., Harris, A.H. ,Wilson, D.E. and Jones, C. (1975).

Mammals of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque,

NM, 360 pp.

Gallo, J.P. (1986). Otters

in Mexico. Journal of Otter Trust. 1: 19-24.

Gallo-Reynoso,

J. P. (1989).

Distribucion y estado actual de la nutria o perro de agua (Lutra

longicaudis annectens Major,

1897) en la Sierra Madre del Sur, México. Ms. Thesis. Universidad

Nacional Autónoma de México. México, D.F. 236

pp.

Gallo-Reynoso,

J.P. (1997). Situación y distribución

de las nutrias en Mexico con énfasis en Lontra longicaudis

annectens Major, 1897. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoologia 2: 10-32.

Gallo-Reynoso,

J.P. and Casariego, M.A. (2005). Nutria

de río, perro de agua. pp. 374-376. In: G.

Ceballos, G. Oliva (eds.). Los mamíferos silvestres de México. Comisión

Nacional para el Conocimiento y uso de la Biodiversidad Fondo de Cultura

Económica México. México, D.F. México 981

pp.

Gore, A. (2006). An inconvenient

truth: the planetary emergency of global warming and what we can do

about it. Rodale Press, Emmaus, PA 325 pp.

Hall, E.R.

and Kelson, K.K. (1959).

Mammals of North America. Ronald Press Company, New York, NY. 1083

pp + 79.

Hall, E.R.

(1981). Mammals of North America. John

Wiley and Sons, New York, NY, 1181 pp. + 90.

Harris, C.J. (1968).

Otters: a study of the recent Lutrinae. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London,

U.K. 397 pp.

Henderson,

J. and Harrington, J.P. (1914). Ethnozoology

of the Tewa Indians. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 56:

1-76.

Hill, W.W. (1982). An

ethnography of Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico. University of New Mexico

Press, Albuquerque, NM. 400 pp.

Hodge, F.W. (ed.)

(1946).

The narrative of the expedition of Coronado, by Pedro de Castañeda,

1542, Zamora. pp. 273-387. In Spanish explorers

in the southern United States: 1528-1543. Barnes and Noble, New York, NY 413 pp.

Johnson, R.

Jr. (2005).

The quiet mountains: a ten-year search for the last wild trout of Mexico’s

Sierra Madre Occidental. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque,

NM. 216 pp.

Julyan, R. (1998). The place names of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque,

NM. 385 pp.

Kidder, AV. (1932). The artifacts of Pecos. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT., 314

pp.

Lariviere,

S. (1999). Lontra

longicaudis. Mammalian

Species. 609:1-5.

Leopold, A.S.

(1959).

Wildlife of Mexico: the game birds and mammals. University of California

Press, Berkeley, CA, 568 pp.

Long, B. (2001). A Survey

of the Rivers of Sonora and Northern Chihuahua for River otter (Lontra

longicaudis). Proposal

to T. & E. Inc., Gila, NM.

LoPopolo, C. (2006).

The history of the Belen grant and the beginning of the settlement

of Belen. [Cincar Publishing, Los Lunas, NM], 23 pp.

Lumholtz,

C. (1973).

Unknown Mexico. Volume 1, Río

Grande Press Incorporated, Glorieta, NM, 530 pp.

McClellan,

J. (1954).

An otter catch on the Gila River in southwestern New Mexico. J.

Mammal.

35: 443-444.

Morfi, J.A. (1782).

Descripcion geografica del Nuevo México. Reprint and translation

by Vargas Rea, Mexico in 1947, 47 pp.

Paine, A.B. (1912).

Mark Twain: a biography; a personal and literary life of Samuel Longhorns

Clements. Harper and Brothers, New York, NY.

Pearce, T.M. (1965).

New Mexico place names. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque,

NM 187 pp.

Polechla, P.J. (1987).

Status of the river otter (Lutra

canadensis) population in Arkansas with special reference to reproductive

biology. University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, xxxi + 383 pp. +

4.

Polechla, P.J. (1988). The Nearctic river otter. pp. 668-682. In: Chandler,

W.J., Labate, L. (eds.). Audubon Wildlife Report 1988/1989. National Audubon Society,

New York, NY. 817 pp.

Polechla, P. (1990).

Action plan for North American otters. pp. 74-79 (Fig. 1 on p. 78)

In: Foster-Turley, P., Macdonald, S., Mason, C.F.

(eds.). Otters: an

action plan for their conservation. 126 pp. Kelvyn Press Inc. Broadview,

IL, 126 pp.

Polechla,

P.J. (2000).

Ecology of the river otter and other wetland furbearers in the upper

Río Grande. Final Report,

Bureau of Land Management, Taos, NM 226 pp.

Polechla,

P.J. (2002a). (18 August) River otter (Lontra

canadensis) and riparian survey of the Los Pinos, Piedra, and

San Juan Rivers in Archuleta, Hinsdale, and La Plata Counties, Colorado.

Final Report to Colorado Division of Wildlife, Denver, CO, 96 pp.

+ endpiece.

Polechla,

P.J. (2002b).

A review of the natural history of the river otter (Lontra canadensis)

in the southwestern United States with special reference to New Mexico.

Report, North American Wilderness Recovery Incorporated, Richmond,

VT, 48 pp.

Polechla,

P.J. (2002c) Otter place names: you “otter” go

there. River Otter Journal 11: 8-9.

Polechla, P.J.,

Gallo, J.P. and Tovar. F. (1987). Distribution,

occupied habitat, and status of the Neotropical river otter (Lutra

longicaudis) in the southern portions of Sierra Madre del Sur,

Mexico. American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY. 32 pp.

Polechla,

P.J., Carrillo-Rubio, E. and Suzan, G. et

al. (in prep). First wildlife law in the borderlands of Mexico and U.S.A.:

beavers and river otters. Book chapter. In: P.J.

Polechla (ed.). The

river otters of the southwestern U.S. and Mexico: past, present, and

future. Cincar Publishing, Socorro, NM.

Polechla,

P.J. and Walker, S. (2008). Range extension and

a case for a persistent population of river otters (Lontra canadensis)

in New Mexico. IUCN Otter

Spec. Group Bull. 25: 13-22.

Radke, W.R. (1999).

Review and approval: Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge, Annual Narrative

Report; Calendar Year 1999, Roswell, NM.

Rivera, P. and Humboldt, A.

von (1807).

Carte de la Route qui méne depuis la Capitale de la Nouvelle

Espagne jusqu'a S. Fe de Nouveau Mexique. Dressee sur les Journaux

de Don Pedro de Rivera et en partie sur les Observations Astronomiques

de Mr.de Humboldt. Dessine et redige par F. Friesen, a Berlin. [map]

(MAGIC, CSEL, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, Call No. G

3302 C 31807 R 5).

Roth, E. and Cockrum, E.L. (1976).

Further records of the southern river otter (Lutra annectens) from

Sonora, Mexico. Journal of the Arizona Academy

of Science. 11: 179.

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

( 2008) (14 October). Washington river otters transplanted to New Mexico. Associated

Press release.

[accessed 14 October 2008 at: http://www.seattlepi.com/local/6420ap_nm_river_otters_return.html]

Stahlecker, D.W. (1986). A survey for the otter (Lutra

canadensis) in Taos and Colfax Counties, New Mexico. Contract

No. 519-75-01. Report to New Mexico Game and Fish Department, Santa

Fe, NM 10 pp.

Sturtevant, W.C. (1983). Handbook of North American

Indians. Volume 10: Southwest. Smithsonian Institute, Washington, D.C.

868 pp.

U.S. Department

of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. (1994). Bitter Lake

National Wildlife Refuge; Annual Narrative Report, Calendar Year 1994.

Roswell, NM

Van Zyll de Jong,

C.G. (1972). A systematic review

of the Nearctic and Neotropical river otters (Genus Lutra,

Mustelidae, Carnivora). Life Sciences Contribution

Royal Ontario Museum.

80: 1-104.

Villa R.B. (1954).

Distribución actual de los

castors in México. Anales de Instituto

de Biología de

la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. 25: 443-450.

Weber, D.J. (1971). The Taos trappers. University

of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK, 263 pp.

Résumé : Repartition

Actuelle et Historique des Loutres Lontra canadensis et Lontra

longicaudis sur le Rio Grande et le Rio Bravo du Nord du Colorado

et du Nouveau Mexique, USA, et Chihuahua, Mexique et Regions Adjacentes

Le réseau hydrographique du Rio Grande est une importante

zone humide des aires arides proches des Etats-Unis et du Mexique

mais elle est à ce jour largement en péril. Il existe

actuellement un désir de restauration des populations de loutres

sur cette rivière. Afin de suivre les lignes directrices de

l'UICN sur la restauration des populations, les biologistes doivent

avant tout évaluer la situation avant d'engager une gestion

favorisant le retour des loutres. La première nécessité est

de connaitre les espèces présentes, leur distribution

et leur abondance relative. Ainsi, les données historiques

et les répartitions actuelles de la Loutre de rivière

(Lontra Canadensis) et de la Loutre néotropicale

(L. longicaudis) sur les zones limitrophes des Etats-Unis

et du Mexique sont synthétisées dans cet article. Les

indices indiquent que les loutres sont originaires de la vallée

du Rio Grande et ont même été enregistrées

dans les langages et les décorations des indiens d'Amérique

tel que le peuple "Pueblo", et ce avant l'installation

des européens. En effet, le premier document espagnol que

nous ayons pu trouver mentionnant la Loutre date du milieu du 16ème

siècle. Par le passé, les loutres étaient sans

doute plus nombreuses que ce que nous pensons et l'une des premières

lois sur la vie sauvage dans cette région tournait autour

d'un moratoire sur le piégeage de la Loutre et du Castor.

Aujourd'hui, les loutres sont présentes sur :

1) le Rio San Pedro du Chihuahua, un affluent du Rio Conchos qui se jette dans

le Rio Grande par le sud-est,

2) la partie amont du Rio Grande près de la frontière du Colorado

et du Nouveau Mexique,

3) la partie centrale de la Rivière "Picos" dans le sud-est

du Nouveau Mexique qui se jette dans le Rio Grande par l'ouest.

Ces données résultent de multiples observations par des naturalistes

compétents mais aussi par des photos de loutres et des indices de présence.

Ces diverses populations fréquentent des aires dont les macro-habitats

sont caractérisés par des rivières à courants rapides à travers

des canyons profonds ou des zones humides secondaires. A vrai dire, des enquêtes

de terrain plus détaillées seraient nécessaires pour affiner

la distribution des loutres sur l'ensemble du système hydrographique du

Rio Grande. Par ailleurs, une étude génétique est absolument

indispensable afin de déterminer les distances génétiques

entre ces populations récemment découvertes. Enfin, un moratoire

sur les translocations pourrait être instauré sur le Rio Grande

afin d'assurer la conservation de ses populations.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Distribucion

Historica y Actual de los Nutrias del Rio (Lontra canadensis, Lontra longicaudis) en la

Cuenca del Rio Grande o Rio Bravo del Norte en Colorado y Nuevo Mexico,

E.U.A., Chihuahua, Mexico, y otras Areas Adyacentes

Le réseau hydrographique du Rio Grande est une importante

zone humide des aires arides proches des Etats-Unis et du Mexique

mais elle est à ce jour largement en péril. Il existe

actuellement un désir de restauration des populations de loutres

sur cette rivière. Afin de suivre les lignes directrices de

l'UICN sur la restauration des populations, les biologistes doivent

avant tout évaluer la situation avant d'engager une gestion

favorisant le retour des loutres. La première nécessité est

de connaitre les espèces présentes, leur distribution

et leur abondance relative. Ainsi, les données historiques

et les répartitions actuelles de la Loutre de rivière

(Lontra Canadensis) et de la Loutre néotropicale

(L. longicaudis) sur les zones limitrophes des Etats-Unis

et du Mexique sont synthétisées dans cet article. Les

indices indiquent que les loutres sont originaires de la vallée

du Rio Grande et ont même été enregistrées

dans les langages et les décorations des indiens d'Amérique

tel que le peuple "Pueblo", et ce avant l'installation

des européens. En effet, le premier document espagnol que

nous ayons pu trouver mentionnant la Loutre date du milieu du 16ème

siècle. Par le passé, les loutres étaient sans

doute plus nombreuses que ce que nous pensons et l'une des premières

lois sur la vie sauvage dans cette région tournait autour

d'un moratoire sur le piégeage de la Loutre et du Castor.

Aujourd'hui, les loutres sont présentes sur :

1) le Rio San Pedro du Chihuahua, un affluent du Rio Conchos qui se jette dans

le Rio Grande par le sud-est,

2) la partie amont du Rio Grande près de la frontière du Colorado

et du Nouveau Mexique,

3) la partie centrale de la Rivière "Picos" dans le sud-est

du Nouveau Mexique qui se jette dans le Rio Grande par l'ouest.

Ces données résultent de multiples observations par des naturalistes

compétents mais aussi par des photos de loutres et des indices de présence.

Ces diverses populations fréquentent des aires dont les macro-habitats

sont caractérisés par des rivières à courants rapides à travers

des canyons profonds ou des zones humides secondaires. A vrai dire, des enquêtes

de terrain plus détaillées seraient nécessaires pour affiner

la distribution des loutres sur l'ensemble du système hydrographique du

Rio Grande. Par ailleurs, une étude génétique est absolument

indispensable afin de déterminer les distances génétiques

entre ces populations récemment découvertes. Enfin, un moratoire

sur les translocations pourrait être instauré sur le Rio Grande

afin d'assurer la conservation de ses populations.

Vuelva a la tapa

Previous | Contents | Next

|