IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

|

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group Volume 28 Issue 1 Pages 1- 60 (January 2011) Citation: Platt, S.G. and Rainwater, T.R. (2011). Predation by Neotropical Otters (Lontra longicaudis) on Turtles in Belize. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 28 (1): 4 - 10 Predation by Neotropical Otters (Lontra longicaudis) on Turtles in Belize Steven G. Platt1 and Thomas R. Rainwater2

1Department of Biological Sciences, P.O. Box C-64, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, Texas, 79832 USA . e-mail: splatt@sulross.edu |

|

| Abstract: We report observations of turtle (Dermatemys mawii and Trachemys venusta) predation by Lontra longicaudis at Cox Lagoon, Belize. On 10 June 1994, we observed an otter swimming with a juvenile D. mawii in its jaws. During a subsequent search (25 June and 5 July 1994) we found 35 D. mawii shells or partially eaten carcasses, and a single, partially eaten adult T. venusta that had apparently been killed by otters. Based on the size of these turtles, juvenile and subadult D. mawii seem most vulnerable to otter predation. Because otter predation of D. mawii appears rare in Belize, and most reproductively mature D. mawii are probably too large to be caught and killed by foraging otters, we do not consider predation by L. longicaudis to be a serious threat to populations of this critically endangered turtle. |

| Keywords: Cheloniaphagy, Dermatemys mawii, diet, endangered species, foraging behaviour, Trachemys venusta. |

| Française | Español |

The neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis) ranges from northwestern Mexico, south to Uruguay, Paraguay, and northern Argentina (Larivière, 1999), but many aspects of its natural history, including diet remain poorly studied (Pardini, 1998; Spínola and Vaughan, 1995). Neotropical otters are considered opportunistic predators (Helder and de Andrade, 1997; but see Pardini, 1998), and the diet consists largely of fish and crustaceans, although mollusks, insects, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and small mammals are also consumed (Alarcon and Simões-Lopes, 2004; Carvalho-Junior et al., 2010; Colares and Waldemarin, 2000; Gallo, 1986; Helder and de Andrade, 1997; Larivière, 1999; MacDonald and Mason, 1992; Pardini, 1998; Passamani and Camargo, 1995; Spínola and Vaughan, 1995). Here we report observations of predation by L. longicaudis on Central American river turtles (Dermatemys mawii) and a neotropical slider (Trachemys venusta) at Cox Lagoon in Belize, Central America.

Cox Lagoon (17°29′N; 88°31′W) is a freshwater wetland in the Belize River drainage, approximately 45 km west of Belize City (Figure 1). The lagoon, a 5 km extension of Cox Creek, is surrounded by swamp forest and open marsh (Hunt et al., 1994; Platt, 1996). Water depth varies depending on season, ranging from <1m during the dry season (December-May) to >3 m in the wet season (June-November). Cox Lagoon is described in greater detail elsewhere (Hunt et al., 1994; Platt, 1996).

|

|

Figure 1. Map of Belize showing approximate location of Cox Lagoon. (click for larger version) |

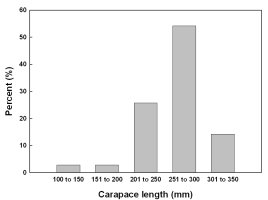

On 10 June 1994 (18h06min), while paddling a canoe along the shoreline of Cox Lagoon we observed an otter enter the water holding a juvenile D. mawii in its jaws. Upon our approach, the otter swam a short distance before submerging with the turtle still gripped in its jaws. Subsequent to this observation we found shells or partially eaten carcasses of 35 D. mawii while searching (25 June and 5 July 1994) for Morelet’s crocodile (Crocodylus moreletii) nests at Cox Lagoon (Platt, 1996; Platt et al., 2008). The turtle remains were found both on the bank and in adjacent shallow water. Freshly killed turtles (n = 4) were typically missing the head, one or more limbs, and often the tail; older, empty shells (n = 31) exhibited scratch and bite marks on the plastron and carapace. The mean (±1SD) straight-line carapace length (CL; measured with tree calipers) of these shells was 263 ± 50 mm (range = 100 to 347 mm). Male and female D. mawii become sexually mature at carapace lengths of 328 and 342 mm, respectively (Polisar, 1996); therefore, the size of the shells we recovered suggests that otters were consuming primarily large juveniles and subadults (Figure 2). We were unable to determine the sex of the predated D. mawii because males and females can only be distinguished by relative tail length and head coloration (Ernst and Barbour, 1989). In addition to D. mawii remains, we found the partially eaten carcass of an adult female T. venusta (CL = 290 mm) in the same area.

|

| Figure 2. Size distribution of Dermatemys mawii (n = 35) killed by Lontra longicaudis at Cox Lagoon, Belize. (click for larger version) |

Several lines of evidence strongly suggest predation of these turtles by L. longicaudis. First, otter tracks and spraints were common along the shoreline, and fresh otter tracks were associated with two carcasses and two shells. Second, the bite marks and missing appendages that we noted among D. mawii remains are consistent with other reports of otter predation on turtles. When feeding on turtles, otters typically consume the head, legs, and often the entrails, while leaving the shell intact (Brooks et al., 1991; Lanszki et al., 2006; Liers, 1951; Ligon and Reasor, 2007; Noordhuis, 2002; Park, 1971; Stophlet, 1947). Other potential turtle predators known to occur at Cox Lagoon include jaguars (Panthera onca), Crocodylus moreletii, and raccoons (Procyon lotor). Jaguars break open the carapace and remove the body (Emmons, 1989), and crocodilians first crush and then swallow the pulverized carcass (McIlhenny, 1935); in contrast to otters, neither predator leaves behind intact shells after feeding on turtles. Raccoons kill and consume turtles in a manner similar to otters, but generally capture turtles on land, with nesting females being particularly vulnerable (Zeveloff, 2002). Because D. mawii are highly aquatic and even nest underwater (Polisar, 1996), raccoon predation of these turtles is undoubtedly rare.

Our observations constitute the first specific report of predation by L. longicaudis on D. mawii and T. venusta, although a general account by Alvarez del Toro et al. (1979) states that D. mawii “sometimes falls prey to otters” (presumably L. longicaudis). Moreover, to our knowledge, turtles have not been previously reported in any dietary study of L. longicaudis. While otter predation of turtles is unusual even when turtles are abundant in otter habitat (Toweill and Tabor, 1982), episodic attacks on several species have been reported (Ultsch, 2006), although factors affecting this behaviour remain poorly understood (Lanszki et al., 2006). Otters (Lontra canadensis and Lutra lutra) occasionally prey on lethargic, over-wintering turtles (Brooks et al., 1991; Lanszki et al., 2006; Liers, 1951; Park, 1971; Ultsch, 2006), but predation on active turtles during warmer months also occurs (Crane and Parnell, 2010; Ligon and Reasor, 2007; Stophlet, 1947). Lanszki et al. (2006) suggested that otters prey on turtles when the availability of their preferred food (fish and frogs) is limited. Because turtle carcasses contain higher levels of crude protein than fish or frogs, and fat content is similar to frogs, cheloniaphagy can yield significant nutritional rewards to otters (Lanszki et al., 2006).

It remains unclear to what extent predation by L. longicaudis affects populations of D. mawii, which is classified as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List (IUCN, 2009) due to continuing over-exploitation for meat and eggs (Polisar, 1994). Turtles are long-lived organisms characterized by a unique suite of coevolved life history traits that include low survivorship of eggs, hatchlings, and juveniles, delayed sexual maturity, and high survivorship among subadults and adults (Congdon et al., 1993). Consequently, turtle populations are demographically sensitive to any increase in mortality among the larger size classes, especially reproductive adults (Brooks et al., 1991; Congdon et al., 1993). Given the depressed status of D. mawii populations throughout Belize (Moll, 1986; Polisar, 1997; Rainwater et al., 2010), otter predation is a potential concern in the conservation of this endangered turtle. That said, it should be noted that predation of D. mawii seems largely confined to juveniles and subadults; demographically important reproductively mature adults (CL to 650 mm; Ernst and Barbour, 1989) are probably too large to be caught and killed by foraging otters. Moreover, predation of D. mawii by L. longicaudis appears to be extremely rare; during fieldwork from 1992 to 1998 in wetlands throughout Belize (Platt et al., 2008; Platt and Thorbjarnarson, 2000), Cox Lagoon was the only site where we found evidence of otters consuming turtles. Spraints collected elsewhere in Belize suggest that L. longicaudis consumes primarily fish and crustaceans (Platt and Rainwater, unpubl. data) as reported in other dietary studies. For these reasons we do not regard otter predation as a serious conservation threat to D. mawii populations.

Acknowledgements - Support for SGP was provided by the Wildlife Conservation Society. TRR was supported by Texas Tech University and an ARCS Foundation (Lubbock, Texas Chapter) scholarship. Additional support was generously provided by Richard and Carol Foster, Monkey Bay Wildlife Sanctuary, Cheers Restaurant, and Robert Noonan (Gold Button Ranch). The field assistance of Lewis Medlock, Travis Crabtree, and Steve Lawson was most appreciated. Research permits were issued by Raphael Manzanero and Emile Cano of the Conservation Division, Forest Department, Belmopan, Belize. Comments from Lewis Medlock improved an early draft of this manuscript. We thank Helene Volkoff, Rick Villareal, and an anonymous reviewer for translation of our abstract into French and Spanish.

REFERENCES

Alarcon, G.G., Simões-Lopes, P.C. (2004). The neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis feeding habits in a marine coastal area, southern Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 21(1): 24-30.

Alvarez del Toro, M., Mittermeier, R.A., Iverson, J.B. (1979). River turtle in danger. Oryx 15: 170-173.

Brooks, R.J., Brown, G.P., Galbraith, D.A. (1991). Effects of a sudden increase in natural mortality of adults on a population of the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Can. J. Zool. 69: 1314-1320.

Carvalho-Junior, O., L.C.P. de Macedo-Soares, L.C.P., Birolo, A.B. (2010). Annual and interannual food habits variability of a Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis) population in Conceição Lagoon, south of Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 27(1): 24-32.

Colares, E.P., Waldemarin, H.F. (2000). Feeding of the Neotropical river otter (Lontra longicaudis) in the coastal region of the Rio Grande Do Sul State, Southern Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 17(1): 1-6.

Congdon, J.D., Dunham, A.E., van Loben Sels, R.C. (1993). Delayed sexual maturaity and demographics of Blanding’s turtles (Emydoidea blandingii): implications for conservation and management of long-lived organisms. Conserv. Biol. 7: 826-833.

Crane, A.L., Parnell, B. (2010). Apalone mutica (Smooth softshell). Predation. Herpetol. Rev. 41: 69-70.

Emmons, L.H. (1989). Jaguar predation on chelonians. J. Herpetol. 23: 311-314.

Ernst, C.H., Barbour, R.W. (1989). Turtles of the World. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Gallo, J.P. (1986). Otters in Mexico. J. Otter Trust 1:19-24.

Helder, J., de Andrade, H.K. (1997). Food and feeding habits of the Neotropical river otter Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora, Mustelidae). Mammalia 61: 193-203.

Hunt, R.H., Perkins, L., Tamarack, J. (1994). Assessment of Cox Lagoon, Belize, Central America as a Morelet’s crocodile sanctuary. In: Ross, J.P. (Ed.). Crocodiles: Proceedings of 12th Working Meeting of the IUCN Crocodile Specialist Group. IUCN Publications, Gland, Switzerland, pp. 329-340.

IUCN. (2009). International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2009.2 (http://www.iucnredlist.org).

Lanszki, J., Molnar, M., Molnar, T. (2006). Factors affecting the predation of otter (Lutra lutra) on European pond turtles (Emys orbicularis). J. Zool. (London) 270: 219-226.

Larivière, S. (1999). Lontra longicaudis. Mammalian Species 609: 1-5.

Liers, E.E. (1951). Notes on the river otter (Lutra canadensis). J. Mammal. 32: 1-9.

Ligon, D.B., J. Reasor, J. (2007). Predation on alligator snapping turtles (Macrochelys temminckii) by northern river otters (Lontra canadensis). Southwest. Nat. 52: 608-610.

MacDonald, S., Mason, C. (1992). A note on Lutra longicaudis in Costa Rica. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 7: 37-38.

McIlhenny, E.A. (1935). The Alligator’s Life History. Christopher Publishing House, Boston.

Moll, D. (1986). The distribution, status, and level of exploitation of the freshwater turtle Dermatemys mawei in Belize, Central America. Biol. Conserv. 35: 87-96.

Noordhuis, R. (2002). The river otter (Lontra canadensis) in Clarcke County (Georgia, USA) – Survey, food habits and environmental factors. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 19(2): 1-10.

Pardini, R. (1998). Feeding ecology of the neotropical river otter Lontra longicaudis in an Atlantic forest stream, south-eastern Brazil. J. Zool. (London) 245: 385-391.

Park, E. (1971). The World of the Otter. B. Lippincott Company, New York.

Passamani, M., Camargo, S.L. (1995). Diet of the river otter Lutra longicaudis in Furnas Reservoir, south-eastern Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 12: 32-33.

Platt, S.G. (1996). The Ecology and Status of Morelet’s crocodile in Belize. Ph.D. Dissertation, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina, USA.

Platt, S.G., Rainwater, T.R., Thorbjarnarson, J.B., McMurry, S.T. (2008). Reproductive dynamics of a tropical freshwater crocodilian: Morelet’s crocodile in northern Belize. J. Zool. (London) 275: 177-189.

Platt, S.G., Thorbjarnarson, J.B. (2000). Population status and conservation of Morelet’s crocodile, Crocodylus moreletii, in northern Belize. Biol. Conserv. 96: 21-29.

Polisar, J. (1994). New legislation for the protection and management of Dermatemys mawii in Belize, Central America. Herpetol. Rev. 25: 47-49.

Polisar, J. (1996). Reproductive biology of a flood-season nesting freshwater turtle of the northern neotropics: Dermatemys mawii in Belize. Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 2: 13-25.

Polisar, J. (1997). Effects of exploitation on Dermatemys mawii populations in northern Belize and conservation strategies for rural riverside villages. In: Abbema, J. van (Ed.). Proceedings: Conservation, Restoration, and Management of Tortoises and Turtles – An International Conference. New York Turtle and Tortoise Society, New York, pp. 441-443.

Rainwater, T.R., Pop, T., Cal, O., Platt, S.G., Hudson, R. (2010). A recent survey of the critically endangered Central American river turtle (Dermatemys mawii) in Belize. Report to Turtle Conservation Fund and Belize Fisheries Department, Belize City, Belize.

Spínola, R.M., Vaughan, C. (1995). Dieta de la nutria neotropical (Lutra longicaudis) en la Estación Biológica la Selva, Costa Rica. Vida Silvest. Neotrop. 4: 125-132.

Stophlet, J.J. (1947). Florida otters eat large terrapin. J. Mammal. 28: 183.

Toweill, D.E., Tabor, J.E. (1982). River otter (Lutra canadensis). In: Chapman, J.A., Feldhamer, G.A. (Eds.). Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Economics. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, pp. 688-703.

Ultsch, G.R. (2006). The ecology of overwintering among turtles: where turtles overwinter and its consequences. Biol. Rev. 81: 339-367.

Zeveloff, S.I. (2002). Raccoons: A Natural History. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C

Résumé : Predation des Loutres Neotropicales (Lontra longicaudis) sur les Tortues à Belize

Nous rapportons ici des observations sur la prédation de tortues (Dermatemys mawii et Trachemys venusta) par Lutra longicaudis à Cox Lgon, Belize. Le 10 juin 1994, nous avons observé une loutre qui nageait en tenant une D. mawii juvenile entre ses machoires. Au cours des recherches qui ont suivi (25 juin et 5 juillet 1994), nous avons trouvé 35 carapaces ou carcasses partiellement mangées de D. mawii ainsi qu’un seul adulte de T. venusta partiellement mangé et apparemment attaqué par des loutres. Vu la taille de ces tortues, il semble que les juveniles et subadultes de D. mawii sont les plus vulnérables à la prédation par les loutres. Etant donné que la prédation sur D. mawii semble rare à Belize et que la plupart des individus D. mawii sexuellement matures sont probablement trop grands pour etre attrapés et tués par des loutres, nous estimons que la prédation par L. longicaudus ne représente pas une menace sérieuse pour la population de cette espèce de tortue en danger critique d’extinction.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Depredación de Tortugas por Nutrias Neotropicales (Lontra Longicaudis) en Belice

Reportamos observaciones de depredación de tortugas (Dermatemys mawii y Trachemys venusta) por Lontra longicaudis en la Laguna Cox, Belice. El 10 de Junio de 1994 observamos una nutria nadando, con un individuo juvenil de D. mawii en sus mandíbulas. Durante búsquedas subsecuentes (25 de Junio y 5 de Julio de 1994) encontramos 35 conchas o cadáveres parcialmente consumidos de D. mawii y un adulto parcialmente comido de T. venusta, que aparentemente habían sido matados por nutrias. De acuerdo al tamaño de estas tortugas, los juveniles y subadultos de D. mawii parecen ser los más vulnerables a la depredación por las nutrias. Debido a que la depredación de D mawii por nutrias es rara en Belice, y a que la mayoría de los individuos reproductivamente maduros de D. mawii son, probablemente, demasiado grandes para ser atrapados y matados por las nutrias, no consideramos que la depredación por L. longicaudis constituya una amenaza grave para esta tortuga, que se encuentra en peligro crítico.

Vuelva a la tapa