IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

|

IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin Volume 28A Proceedings Xth International Otter Colloquium, Hwacheon, South Korea Citation: Akpona, H.A., Sinsin, B. and Mensah, G.A. (2011) Monitoring and Threat Assessment of the Spotted-Necked Otter (Lutra maculicollis) in Southern Benin Wetlands . Proceedings of Xth International Otter Colloquium, IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 28A: 45 - 59 Monitoring and Threat Assessment of the Spotted-Necked Otter (Lutra maculicollis) in Southern Benin Wetlands H.A. Akpona1,B. Sinsin1 and G.A. Mensah2

1

Laboratoire d’Ecologie Appliquée, Faculté des Sciences Agronomiques, Université d’Abomey-Calavi. BP : 482 Parakou, Bénin e-mail: akpona@gmail.com / bsinsin@gmail.com |

|

|

Abstract: Otters are a very poorly studied species in most of Africa and Benin is no exception. This is due to their inaccessible habitat (river valleys), their retiring behaviour, and the difficulty of having no specific survey methods. An interview survey of local people was carried out in 2004 by the Laboratory of Applied Ecology in Southern Benin wetlands (6°28’N to 7°N; 2°23’E to 2°35’E) to assess the threats to spotted-necked otters. The results showed that yearlings dominated the demographic structure of the population (46.7%) and that males outnumbered females. |

| Keywords: Lutra maculicollis, accidental capture, conservation, Benin |

| Française | Español |

INTRODUCTION

Despite intense theoretical work, data collection, analysis and management, most fish populations are overexploited and many fisheries have collapsed (Ludwig et al., 1993) with a direct consequence on wetland wildlife. Overexploitation is a major threat to many species as a result of increasing human population size and the increased exploitation of the wildlife resource due to the use of guns, mechanised transport and chain saws, along with increased access to markets. This pattern of overexploitation applies to innumerable other species of plants and animals as well as otters.

Otters are a very under-researched species in most parts of Africa. Two species occur in Benin: the Cape Clawless otter (Aonyx capensis) and the spotted-necked otter (Lutra maculicollis) (Alden et al., 2001). Despite L. maculicollis being classified as Vulnerable by IUCN (2006), it is highly threatened in Benin and its conservation status is not known. The current threats to the populations of spotted-necked otter (L. maculicollis) are caused by the local human population because of damage to fishermen’s bow nets (Kidjo, 2000), by their use for food and for ritual practices (Amoussou, 2003). This pressure is currently strong and is probably greater than that on manatees and hippopotamuses as capture of this animal does not require expensive investment in equipment (Amoussou, 2003). However, in Southern Benin the wetland niche habitats of the species are gradually in decline due to the effect of pollution and late bushfires (Kidjo, 2000). The high level of threats to this small mammal and its habitat could cause its extinction locally, together with many other fauna species, if no conservation actions are taken (Akpona, 2004).

This study is designed to answer the following questions in order to assess implications for the conservation of the species in Benin.

- How are age and sex classes represented in the hunting and capture records of spotted-necked otters in the Ouémé valley / Hlan river complex?

- What are (a) the rate of L. maculicollis’ damage to the local human activities in the study area? and (b) what impact does the local population behaviour have on the decline in spotted-necked otters’ numbers?

- How do local human populations and spotted-necked otters’ populations adapt themselves to the conflict cause by their co-utilisation of the same resources?

- Will the level of threats on spotted-necked otters’ populations, due to the human / otter conflict, allow the species to survive in Benin and what are the management strategies which could significantly improve conservation of Lutra maculicollis?

METHODS

Study area and species

Two wetlands in Southern Benin were investigated: the Oueme valley (6°28' N to 7°N; 2°23' E to 2°35' E) and the Hlan river where the flooded forest of Lokoli (7°02' N to 7°05 ' N; 2°15' E to 2°18' E) covering approximately 500ha is found (Sinsin and Assogbadjo, 2002).

The studied ecosystems are used as a refuge by an impressive diversity of aquatic wildlife including the endemic Red-bellied monkey Cercopithecus erythrogaster erythrogaster (Sinsin and Assogbadjo, 2002) and the spotted-necked otter (L. maculicollis).

Study design and data collection

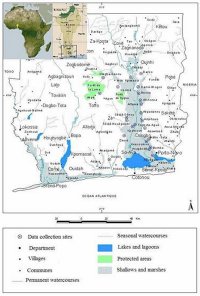

A survey based on questionnaire and focus group discussions was conducted in 35 bordering villages and on 5 animals based medicine markets in the districts of Adjohoun, Toffo, Zinvié, Zogbodomey, Bonou, Dangbo and Aguégués (Fig. 1). A randomised sample of 204 interviewees was taken which included different socio-professional groups: fishermen (134), hunters (24), animal based medicine sellers (31) and ‘traditional’ practitioners (15). Villages and interviewees were chosen according to the different ethnic groups, the socio-professional groups, communities and position in relation to the river and valley.

|

| Figure 1. Distribution of data collection sites |

A poster featuring high quality images of the two species of otters was used to ensure that the interviewee recognized the species and to reduce the risk of misidentification. These interviews were later re-enforced by local people, who provided skins and others organs conserved for different purposes, and by research on field signs or live observations.

Surveys consisted in the collection of spotted-necked otters presence data, the use of linear measurements on remaining animals’ organs, working with fishermen in the field to sample fish species captured (in order to assess their species richness), taking an inventory of plant diversity in otter habitat, and assessing otter damage to fishermen’ equipment and to record how fishermen adapt themselves to otter damage (different types of traps, developing otter - friendly techniques, etc.).

Population structure of captured spotted-necked otters

To assess the demographic structure of hunted otters, we analysed captures from the last five years and measured the remains of spotted-necked otters’ organs. We established a reference collection to categorise captured spotted-necked otters’ specimens in age and sex classes using the previous results of Perrin and D’Inzillo Carranza (1999b) combined with information from, and the folklore of, fishermen. The Head Length (HL) was considered because it was the organ, which is mainly preserved for medicinal and mystical purposes. For this study we classified a specimen as juvenile (HL≤ 100mm), yearling (100mm <HL ≤120mm) and adult (HL> 120mm). For the remainder of the organs, if possible, sex was confirmed by the presence or absence of genital organs and teats.

Evaluation of spotted-necked otter damage on local population activities

It was recognised that spotted-necked otters destroy fishing equipment and this generates conflict. Evaluation of otter damage was carried out with 134 fishermen. During a period of seven (7) months we recorded the amount of fishery gear destroyed by spotted-necked otters out of the total amount of gear possessed by each fisherman.

Impact of human pressure on spotted-necked otter population decline

We inventoried hunting and capture techniques for spotted-necked otters and recorded the number of males, females, juveniles, yearling and adults captured, in order to analyse the efficiency of traps according to age and sex. We followed and recorded the number of traps that had captured a spotted-necked otter, and the total number of traps possessed by each fisherman for the same period.

We recorded capture in two categories: chance captures, and deliberate trapping. We also investigated the trapping methods. We recorded the number of persons who use each type of trap in order to know their relative importance in otter hunting.

Records of the studied species’ capture were collated for the last 30 years; including the socio-professional group (fisherman, hunter, etc.), the village or site of capture, the time of capture and the sex.

Investigation of how local populations and spotted-necked otters adapt themselves to the conflicts between them

We benefited from local ecological knowledge on how otters adapt themselves to the conflicts between them. We also investigated distribution of spotted-necked otters in order to analyze the impact of high anthropogenic pressure on the habitat use by the species. For example, if pressure is high on a site do otters migrate towards other sites?

We inventoried ecologically friendly techniques used by the human population to mitigate these conflicts. By conducting interviews and field surveys we also investigated the importance of unsustainable strategies developed by fishermen as a response to otter predation.

Data analysis

We calculated the percentage of each age and sex class and determined the age ratio (juveniles to yearlings and adults) and sex ratio (males to females) to characterise the population structure of captured otters.

To assess threats, we calculated some parameters in percentages:

Destruction rate of fishery equipment: DR (%) = Amount of fishing gear destroyed X 100 / Total amount of fishing gear possessed by each fisherman

Efficiency Rate: ER (%)= Number of traps that have captured a spotted-necked otter X 100 / Number of traps possessed by each fisherman for the same period.

We used Student t-test to test if there is a significant difference between:

- Each sex class capture records in relation to age classes, villages and capture techniques.

- Each age class capture records in relation to capture techniques and in relation to villages.

We used a factorial analysis of correspondence to:

- show the specialisation of capture techniques in relation to each sex class and for the total;

- group together villages in relation to capture period categories;

- evaluate the specialisation of capture techniques in relation to each age class.

RESULTS

Demographic structure of captured spotted-necked otters according to age and sex class

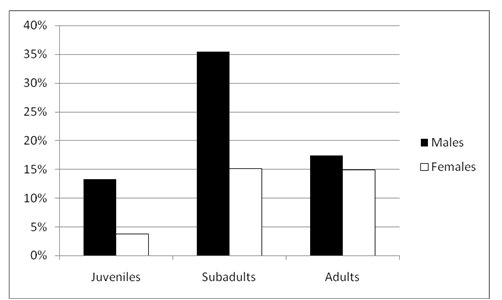

We noticed that the hunting techniques developed in the study area capture all age and sex categories. We do not identify a significant difference between sex classes according to age (P=0.0876) or capture techniques (P=0.1086). However, we notice that males were captured more than females in “Whédos” (traps and hooks in bow nets). Sex ratio calculated globally (1.74 /1) is two 2 males for a female. This parameter varies from one age class to another with approximately 4 males for a female (juveniles) and 3 males for a female (sub-adults) (Table 1).

| Table 1: Variation of sex-ratio for different age classes | |

| Age classes | Sex - ratio |

| Juveniles | 3.48 :1 |

| Yearlings | 2.33 :1 |

| Adults | 1.17 :1 |

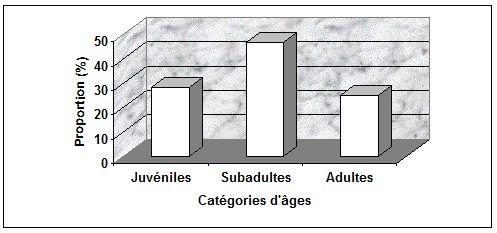

There were no significant differences between age classes and capture materials (P=0.511; 0.715 and 0.518 respectively for juveniles cf yearlings, yearlings cf adults and juveniles cf adults). We investigated which hunting techniques are more successful in the capture of each age class. Six techniques capture juveniles against four (4) and three (3) respectively for adults and yearlings. Sub-adults were more represented in capture records (46.7 %) compared to 28.3% and 25 % respectively for juveniles and adults (Fig. 2a and 2b). Finally, we recorded those techniques that are not selective according to age and sex categories.

|

| Figure 2a. Structure of spotted-necked otters captured according to age |

|

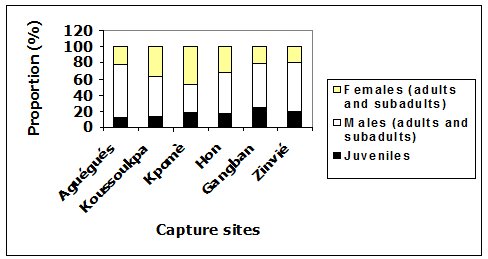

| Figure 2b. Structure of spotted-necked otters captured according to age and sex |

Data showed that juveniles and their parents exploit different sites and males and females exploit different concentration areas. We identified a significant difference between the number of males and females captured (P=0.021). More females were captured in Koussoukpa, Kpomè and Hon whereas males were concentrated at Zinvié and Koussoukpa and juveniles on the Gangban, Zinvié sites (Fig. 3). There are no significant differences between each age class capture records in relation to villages. Age-ratio varies from one site to another and the highest value is obtained at Zinvié (1 juvenile to 4 adults) (Table 2).

|

| Figure 3. Importance of age and sex classes of spotted-necked otters captured in relation to sites |

| Table 2: Variation of sex-ratio for different age classes | |

| Sites | Age - Ratio |

| Aguégués | 0.13 |

| Koussoukpa | 0.14 |

| Kpomè | 0.21 |

| Hon | 0.2 |

| Zinvié | 0.25 |

Evaluation of spotted-necked otter damage on local human population activities

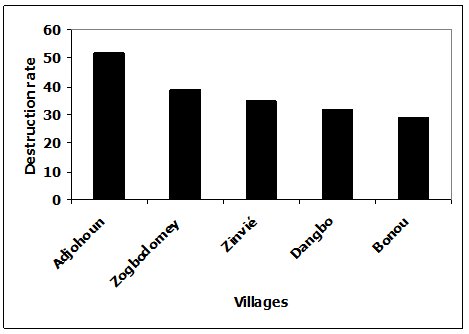

The results showed that spotted-necked otters destroy fishery traps and gear and reduce the fish catch both quantitatively and qualitatively. 90% of targeted populations are fishermen and use bow nets for their daily catch. The number of bow nets used per year per fishermen varies from 40 to 200. The destruction rate of bow nets by spotted-necked otters varies from 29.3% (at Bonou) to 52.1% in the Adjohoun district (Fig. 4).

|

| Figure 4. Destruction rate of bow nets by spotted - Necked otters. |

The impact of human pressure on the spotted-necked otter population decline

Hunting and capture

The ritual, food and medicinal importance of spotted-necked otters in the Oueme valley / Hlan river complex, together with the species’ damage to fishery equipment, explains the keen interest of local people in their hunting and capture. The intensity of hunting / capture is greatest during the dry season because of the bushfires which increase accessibility and visibility around water points and the migration of otters towards shallows where their densities become greater. Those parameters increase the probability of hunting and capture success. However, the local people do not specialise in otter hunting as the animal is difficult to catch. 44% of fishermen and hunters recognized that the capture of spotted-necked otters is mainly due to chance because it tends to happen when least expected. This increases the financial value of its organs. Thus men or women who capture otters receive enhanced status in the targeted villages. Each year, local communities develop and improve selective hunting techniques, increase pollution of water points and overexploit wetlands resources both to compete against otter damage and for all the socio-economic and cultural importance of the species. Eight hunting methods that are not selective according to sex and age have been developed in the studied area.

Accidental catch should be added to these hunting methods along with the other threats linked to the spotted-necked otters’ habitat: ponds polluted by chemicals for fishing, the common exploitation of water points and over fishing in competition with otters.

Accidental catching (Chance capture)

Strategies developed in this category are so called because they are not directly aimed at the capture or hunting of spotted-necked otters. The material used is generally fishery equipment, which includes bow nets, nets, hooks, or other aquaculture techniques locally called Whédos1 and Acadjas2.

The efficiency of those strategies is low.

Spotted-necked otter hunting

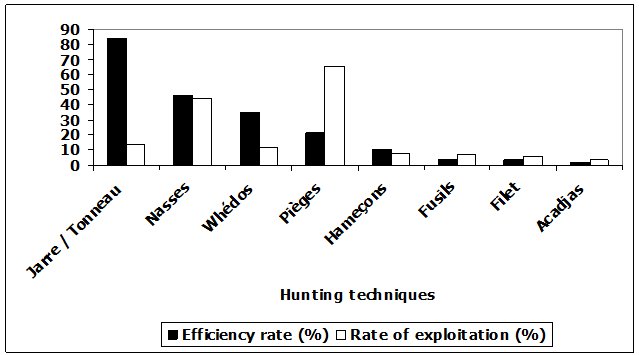

Figure 5 illustrates the use and the efficiency rate of the various hunting strategies. The first four are the most effective techniques used.

|

| Figure 5. Efficiency and exploitation rate of hunting techniques |

Historical and current records of spotted-necked otter hunting or chance capture

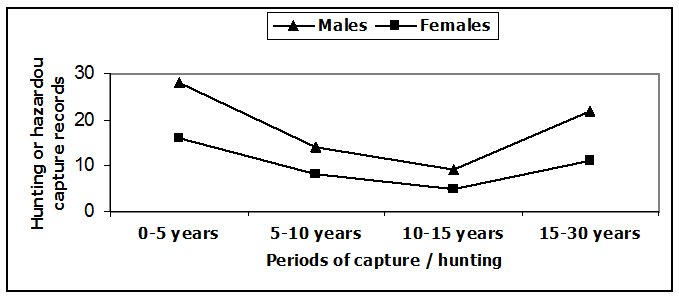

The number of spotted necked otters captured or hunted for the last 30 years showed a difference according to sex and over time (Fig. 6).

|

| Figure 6. Evolution of capture over the last 30 years |

Males are always captured in greater numbers than females. For the period (≥15 years), capture records were high at Lowé, Hlankpa, Sèdjè, Agbon and Kpomè. Those sites were recognized by local communities as potential sites frequented by the species in the past. During this period, Spotted-necked otters were abundant because of the low pressure on them. According to local perceptions, the animals were frequently accidentally captured in nets, bow nets and other fishing gear. They were not used to those accidental traps and this increased the probability of their capture. In contrast, during the period (5 - 15 years), capture records decreased but were concentrated at Hon, Hêtin, Gogbo (Gogb), Dekanmè (Deka) and Hozin (Hozi) sites; however the number of wetlands users increased. Our study suggests that otters develop strategies to escape accidental captures but, at the same time, fishermen had started the development of new efficient hunting techniques. For the last five (5) years, hunting records have also increased with human population growth and improvement in hunting techniques. Sites where there have been more Spotted-necked otter captures during the last 5 years are around Lokoli swamp forest which provides good habitat.

Threats to spotted-necked otters’ habitat and feeding

Wetland drying and degradation

Wetlands are drained for fishing during the dry season when the level of water is low. The practice of using a motorized pump was particularly used in the Bonou community and this method has gradually been extended to the other communities in the Oueme valley as more fishermen bought motorised pumps. This strategy is not selective according to the fish age and sex classes which are all represented in otter diet. Thus, the last remaining food available for otters in the dry season is removed. This situation affects otter survival and distribution and obliges Spotted-necked otters to migrate towards other sites where survival conditions are better. To this specific threat, is added deforestation, erosion and pollution due to the use of oil-based fuels together with uncontrolled bushfires.

The practice of using poisoned bait laced with caustic soda

This practice is common in the Oueme valley and constitutes, according to practitioners, one method of moving individuals or spotted-necked otter groups away from fishing sites, where damage was frequently observed, when hunting strategies were unsuccessful. The procedure consists of partially dissecting a large specimen of the electric fish (Protopterus annectens) into which caustic soda is introduced. This poisoned bait is deposited near bow nets on fishing sites where damage has been recently noticed. When the bait is consumed by otters, they start howling and flee. According to local experience, when hearing one spotted-necked otter howling, the other animals disappear from the site and the fisheries gear destruction rate is reduced. It is a disastrous practice which affects not only Spotted-necked otters’ survival but other aquatic wildlife species such as crocodiles and mongooses that also feed on fish.

Concurrent exploitation of fishes by the human population and otters

Facing the rapid growth in the population of fishermen and the risk of overexploitation of fisheries, it becomes difficult for Spotted-necked otters to hunt successfully. In addition, in the Ouémé valley fishermen use disastrous and unselective techniques such as fishing with nets with too small a mesh called locally "Medokpokonou". This constitutes an added threat to spotted-necked otters which must spend enormous quantities of energy in feeding.

DISCUSSION

Patterns in the spatial distribution of spotted-necked otters

According to Sandell (1989), the spatial organisation of males is influenced by three resources: food, cover and receptive females while the home range area of females is determined by food and cover, and adjusted so that food availability is sufficient when food resources are low. Consequently, males have larger home range areas than females (Perrin et al., 1999c) and this explains the abundance of males to females in hunting records (63.5 % against 36.5 %). Analysis of distribution reveals the exploitation of habitat by all age and sex categories and an abundance of females at Koussoukpa, Kpomè and Hon villages bordering the swamp forest of Lokoli. Perrin et al., 1999c demonstrate at Kwazulu-Natal Drakensberg (South Africa) a strong correlation between female Spotted-necked otter home range and food availability. The flooded ecosystem of Lokoli offers good conditions for fish reproduction and consequently a quasi-permanent availability of food for the species. The branching root structure of the Raffia palm tree (Raffia hookeri) and stilt roots developed by other waterside plants create suitable habitat which is used as refuge sites for fish spawning and nursery sites and provide the species diversity which serve as food for the otters. Moreover, the sites of Kpomè and Hon are contiguous with the Lokoli flooded forest, which is unused for Raffia palm extraction, and is under-exploited by fishermen because of its distance from riverbanks.

At Gangban and Zinvié in the Ouémé valley, otter juveniles are more represented in the records. This situation is not surprising when we consider that juveniles are not skilled at escaping from traps. Sub-adults, which have the biological role of protecting juveniles, are also highly represented in hunting records. Moreover, the rapid growth of fishermen numbers, the level of deforestation and erosion and the open aspect of the valley contribute to the exploration of all parts for fishing and otter hunting.

L. maculicollis is regarded as social but must modify its degree of sociality in response to food resource availability. According to the marginal value theorem, when a predator is hunting in a patch, prey availability decreases with the time in the patch because of the disturbance caused by the predator. If more predators hunt at the same time in the same patch, the disturbance effect is amplified, and hunting success is lower than if a single individual is hunting in the patch (Perrin et al., 1999c). Considering that in the Ouémé valley / Hlan river complex, fishermen also act as predators of the fish, the disturbance effect is increased and the otters’ hunting success decreases considerably. To adapt to this, L. maculicollis populations in Benin are obliged to (1) explore their habitat in small groups in order to increase the probability of capturing their prey and (2) destroy the bow nets placed by fishermen. The second strategy is an opportunist method developed by small carnivores (such as Spotted-necked otters) generally considered as opportunistic feeders (Maddock, 1988). Since the species is not territorial, the minimum area required to maintain a viable population is likely to be dependent on food resource availability (Perrin et al., 1999c). This perpetual search for food explains the migration of L. maculicollis towards shallows during the dry season.

The impact of conflicts on Spotted-necked otters’ survival

The spotted-necked otter (Lutra maculicollis) is a species sought for hunting and usually for population consumption (Kidjo, 2000). The species is recognized as aggressive, a good swimmer and, because of its adaptation to the hunting techniques developed locally, L. maculicollis is difficult to capture. Even if those abilities help spotted-necked otters to escape from trapping, the keenness for, and the highly developed love of, hunting and the improved hunting techniques that have been developed by the local people constitute a threat. In addition, the hunting methods are non-selective and sub-adults are more represented in the capture records. This situation is damaging for the success of the otter population not only because of the important role of yearlings as future breeders, but as they also fulfil a biological role as protectors of juveniles. Our results showed that the otters’ habitat, feeding and consequently survival, are affected by different local practices such as the draining of shallows for fishing during the dry season, the practice of poisoning bait with caustic soda and the concurrent exploitation of fish by both humans and otters. Presence and permanence of water, abundance of fish for feeding and density of vegetation play an important role in the choice of habitat by Spotted-necked otters. It is known that abundance of fish and vegetation depends on the availability of water. For this reason, the presence and permanence of water is a determinant for otter presence and consequently the draining of shallows for fishing during the dry season constitutes an important threat to spotted-necked otter populations at that time.

The intensive exploitation of water points for fishing constitutes a human / otter competition in the face of which the chances of survival and success of the otters is tiny. This conflict is similar to that existing between fishermen and crocodiles (Kpéra, 2002). To overcome it otters destroy fishery bow nets and in return, fishermen have developed harmful methods of dissuasion such as the use of poisoned baits. This situation causes the death of otters. Moreover, no cultural practices proscribe use of the otter for other purposes, and 48% of interviewees do not want spotted-necked otters for economic reasons.

Analysis of historical and recent otter hunting records shows a fluctuation in the catch rate. This depends on the skills of both otters and fishermen in developing new, adaptive strategies to manage conflicts and on the rate of human population growth, which significantly increases the human need to earn a living. From 1979 to 2002, the population of Benin has doubled from 3.3 to 6.7 million. The average annual population growth is 3.5%. The south of the country (where the study area is located) has the highest population density with 150 inhabitants per km², while the centre and the north have only 20 inhabitants per km2 (INSAE, 1979, 2002). The rapid population growth and the industrial development during the past few decades have caused an increasing pressure on land and water resources in almost all regions of the world (Refsgaard and Knudsen, 1996). This phenomenon of population growth is high in Africa in general and increases the demand for water for domestic, agricultural and other uses in particular in countries, which are dependent on agriculture such as Benin (Sintondji, 2005).

The plight of the spotted-necked otter (L. maculicollis) becomes increasingly critical considering its imminent disappearance from some sites where its past presence was confirmed. This is the case in the Bonou community in the Ouémé valley where all interviewees confirmed the absence of the species.

This small mammal, classified in the red list of IUCN as Vulnerable is at high risk in the southern Benin wetland and extinction could occur if the actual threats are maintained. Strategic and sustainable conservation and management programs must be developed for the safeguard of the species and its habitat.

Implications for sustainable management and conservation

Sustainability is regarded as the guiding principle for biological conservation (Eraldo and Costa Neto, 2005). According to the IUCN draft Guidelines (Glowka et al., 1994), the exploitation of a given species is likely to be sustainable if:

- It does not reduce the future use potential of the target population or impair its long-term viability;

- It is compatible with maintenance of the long-term viability of supporting and dependent ecosystems; and

- It does not reduce the future use potential or impair the long-term viability of other species.

Considering the level of threats to the spotted-necked otter population in Southern Benin, none of those criteria were satisfied. We can consider that spotted-necked otters are not sustainable in Benin and it is urgent that management strategies are developed. The spotted-necked otters’ hunting strategy, if properly managed, can be compatible with an environmental conservation programme in which the use of natural resources can and must occur in such a way that human needs and the protection of biodiversity can be guaranteed (Andriguetto-Filho et al., 1998). For this reason, the human / otter conflicts should be viewed within its cultural dimension. This cultural perspective includes the way people perceive, use, allocate, transfer, and manage their natural resources (Johannes, 1993). Since people have been using these animals for a long time, suppression of use alone will not save them from extinction (Eraldo and Costa Neto, 2005).

Kunin and Lawton (1996) attest that as far as conservation is concerned, the extraction rate of a renewable resource should not exceed the renovation rate of that same resource. The logic of sustainable exploitation is simple: it is to remove individuals at the rate at which they would otherwise increase (Caughley and Sinclair, 1994). Due to their specialised habitat requirements and difficulty of access (valley, rivers), their behaviour, the difficulty of capturing them and the lack of specific census methods (Akpona, 2004), it is not easy to estimate the renovation rate. Extraction rate could be estimated if we could establish a good monitoring system. This necessitates the identification of the focal landscapes in Southern Benin wetlands but it is difficult for us to monitor spotted-necked otter exploitation in order to evaluate the balance between extraction and renovation rate.

Another alternative for the recovery of endangered species is to turn them into manageable resources in the way of traditional farming systems, where they would be reared using both folk and scientific techniques (Costa-Neto, 1999). Methods for raising spotted-necked otter’s domestically has not been investigated and this constitutes the main constraints for people (52%) who wish to raise the species.

Taking these constraints into account, one solution will be to consider the spotted-necked otter (L. maculicollis) as a flagship species both for scientific capacities building and for conservation. In the Hlan river / Ouémé valley’ complex, it was locally recognized that there were no spotted-necked otters present. This was confirmed by Lamarque (2004) and reveals that spotted-necked otters play an important ecological role in Benin wetlands. The species is known as an excellent indicator of the quality of the wetlands (IUCN, 2002), because they are at the top of the food chain. More biodiversity could be protected in situ if the few species that attract the most popular support (the ‘flagship’ species) had a distribution that also covered the broader diversity of organisms. Conservationists often choose flagship species strategically from among the largest and most charismatic threatened mammals in order to raise public support for conservation (for a review, see Leader-Williams and Dublin, 2000 in William et al., 2000). It is often argued that these flagships might also act as ‘umbrellas’ for conserving many other species, if the flagships have particularly broad ecological requirements (e.g. Shrader-Frechette and McCoy, 1993 in William et al., 2000). The conservation of such flagship species usually has benefits for associated less spectacular species (Eisner et al., 1995).

This option will be successful if strategic conservation actions are developed to assess the social and environmental impacts of the conflict, to test, evaluate and promote ecologically friendly deterrent techniques on a large scale, to involve the human population in the conservation process through awareness, sensitization, symbolic support for fishermen and restoration of wetlands with medicinal and other important plants which will also be useful for communities. Conflicts with fishermen, who opposed L. maculicollis presence have to be co-managed efficiently by creating new opportunities for local populations bordering the Hlan river and Ouémé valley in southern Benin.

However the goal of conservation actions developed above are satisfied, the capacity of conservationists in decision making depends on the development of further research. Such research will need to study distribution, reproduction, activity patterns, identification of vital habitat, use of space, food habits and availability and habitat use by spotted-necked otters in Southern Benin.

REFERENCES

Akpona A. H. (2004). Facteurs de conservation des loutres au Sud du Bénin: Cas de la forêt classée de la Lama et des corridors avec les zones humides de la vallée de l’Ouémé. Mém.d’Ing. Agr.FSA /UAC. Bénin. 111p.

Alden P. C., Etes R. D, Schilter D., McBride B. (2001). Photo guide des animaux d’Afrique. Delachaux et Niestlé. Paris. pp. 443, 566 – 567.

Amoussou K. G. (2003). Etude exploratoire sur les petits mammifères aquatiques menacés de disparition (l’hippopotame, le lamantin et la loutre) dans les terroirs villageois au centre et au Nord Bénin. AVPN – ONG / CENAGREF, Bénin. 50p + annexes.

Andriguetto-Filho J.M., Kruger A.C., Lange M.B.R. (1998). Caça, biodiversidade e gestao ambiental na area de Proteçao Ambiental de Guaraqueçeba, Parana, Brasil, Biotemas 11: 133-156

Caughley G., Sinclair A.R.E. (1994). Wildlife ecology and management. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications Ltd.

Costa-Neto E.M. (1999). Healing with animals in Feira de Santana city, Bahia, Brazil. J. Ethnopharm. 65: 225 - 230.

Eisner T., Lubchenko J., Wilson E.O. Wilcove D.S. Bean M.J. (1995). Building a scientifically sound policy for protecting endangered species. Science 268: 1231 - 1232.

Eraldo M.and Costa-Neto EM. (2005). Animal based medicines: biological prospection and the sustainable use of zootherapeutic resources. Anais da Academia Brasileira de ciências, 77: 33-43.

Glowka L., Burherme-Guilmin F and Singe H. (1994). A guide to the convention on biological diversity. Gland: IUCN, 245 p.

INSAE (1979). Recensement Général de la Population et de l´Habitat (RGPH). Tableaux statistiques, Volume National (Tome 1: mars 1979). Ministère du Plan, Cotonou, Bénin.

INSAE (2002). Recensement Général de la Population et de l´Habitat (RGPH). Résultats provisoires. Ministère du Plan, Cotonou, Bénin. 4 p.

IUCN (2002). On recherche des informations sur les loutres africaines. Brochure. IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group OTTER- ZENTRUM. Germany. 4p.

IUCN (2006). Lutra maculicollis.

[http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/12420/0 Accessed 29/07/11]

Johannes, R.E. (1993). Integrating traditional ecological knowledge and management with environmental impact assessment. In INGLIS J.T. (Eds). Traditional ecological knowledge: concepts and cases, Ottawa: International program on Traditional Ecological knowledge and International development Research centre, p. 33-39

Kidjo C.F. (2000). Estimation des indices de présence et étude de la stratégie de protection et de conservation des loutres (Aonyx capensis - Scinz, 1821 et Lutra maculicollis - Lichtenstein, 1835; Lutrinae- Mustelidae) dans les zones humides du Sud- Bénin. Rap. prov. ABE – PAZH. Bénin. 26p.

Kpera G. N. (2002). Impact des aménagements d’hydraulique pastorale et des mares naturelles sur la reconstitution des populations de crocodiles dans les sous- préfectures de Nikki, Kalale, Segbana, Kandi, Banikoara, Kerou, Ouassa- Pehunco et Sinendé. Mém. d’Ing. Agr. FSA/UAC. Bénin. 113p+annexes.

Kunin W.E., Lawton J.H. (1996). Does biodiversity matter? Evaluating the case for conserving species. In GASTON K.J. (Ed). Biodiversity: a biology of numbers and differences, Oxford: Blackwell Science, 283- 308.

Lamarque F. (2004). Les grands mammifères du complexe WAP. UE/CIRAD/ ECOPAS.

Ludwig D., Hilborn R., Walters C. (1993). Uncertainty, resource exploitation and conservation: lessons from history. Science, 260: 17 - 36.

Maddock A. H. (1988). Niche occupation in a community of small carnivores. PhD Thesis; University of Natal, Pietermaritzburgh.

Perrin M.R., D’Inzillo Carranza I. (1999a). Activity patterns of the spotted- necked otter in the Natal Drakensbourg, South Africa.S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res., 30: 52-53.

Perrin M.R., D’Inzillo Carranza I. (1999b). Capture, immobilisation and measurements of the spotted- necked otter in the Natal Drakensbourg, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res., 29: 1-7.

Perrin M.R., D’Inzillo Carranza I., Linn I. J. (1999c). Use of space by spotted- necked otter in the Natal Drakensbourg, South Africa. S Afr J Wildl. Res, 30(1): 15-21.

Refsgaard, J.C., Knudsen, J. (1996). Operational validation and intercomparison of different types of hydrological models. Water Resources Research 32, p. 2189-2202.

Sandell, M. (1989). The mating tacties and spacing patterns of solitary carnivores. In Gittleman, J.A. (ed,). Carnivore behaviour ecology and evolution (pp. 164-183). Chapman and Hall. London.

Sinsin B., Assogbadjo A. (2002). Diversité, structure et comportement des primates de la forêt marécageuse de Lokoli au Bénin. Biogeographica, 78(4): 129-140.

Sintondji, L.O.C. (2005). Modelling the rainfall-runoff process in the Upper Ouémé catchment (Terou in Bénin Republic) in a context of global change: extrapolation from the local to the regional scale. Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades (Dr. rer. nat.) der Mathematisch- Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn

Williams P.H., Burgess N.D., Rahbek C. (2000). Flagship species, ecological complementarity and conserving the diversity of mammals and birds in sub-Saharan Africa. Anim. Cons., 3: 249-260.

Résumé : Suivi et Évaluation des Facteurs de Menaces sur la Loutre à Cou Tacheté (Lutra maculicollis) dans les Zones Humides au Sud du Bénin

Les loutres sont très peu connues dans la plupart des pays africains dont le Bénin. Cette situation est due à l’inaccessibilité de leur habitat (rivières, vallées), leur comportement ainsi que la difficulté à disposer de méthodes spécifiques d’investigations. Un monitoring a été réalisé par le Laboratoire d’Ecologie Appliquée sur la base de questionnaire et de collecte de données de terrain a permis d’identifier les menaces pesant sur la survie de la loutre à cou tacheté (Lutra maculicollis) au Sud Bénin. A travers les résultats obtenus, on note que 8 techniques de capture sont utilisées et améliorées d’années en années et que l’exploitation abusive des pêcheries, la pollution des eaux par les produits chimiques sont autant de facteurs de menaces. Nous estimons que l’espèce est en très menacée dans les zones humides concernées et risque l’extinction si les tendances actuelles sont maintenues. Des stratégies conséquentes sont à développer sur la base d’une approche participative pour évaluer et traiter les conflits tout en considérant la loutre à cou tacheté comme une espèce parapluie pour sauvegarder l’espèce et son habitat.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen:Seguimiento y Evaluacion de la Amenaza sobre la Nutria de Cuello Manchado (Lutra maculicollis ) en el Sur de los Humedales de Benin

Las nutrias son especies poco estudiadas en Africa y Benin no es la excepción. Esto es debido a su habitat inaccesible (valles de ríos), su comportamiento de desbandada y la dificultad de no tener metodos de seguimiento específicos. Una encuesta de la población local fue llevada a cabo en el año 2004 por el laboratorio de eocología aplicada (Laboratory of Applied Ecology) en el sur de los humedales de Benin (6°28’N to 7°N ; 2°23’E to 2°35’E) para evaluar las amenazas sobre la nutria de cuello manchado. Los resultados mostraron que los cachorros de un año dominan la estructura demográfica de la población (46.7%) y que el número de machos supera el de hembras. Ocho métodos de caza han sido desarrollados y mejorados cada año por la población local en el área de estudio y registros de esta caza fueron utilizados para determinar edad y sexo. Adicional a esta caza delibarada, captura accidental y amenazas relacionadas con el habitat han sido incluidas. Se encontraron estanques contaminados con productos químicos utilizados para la pesca, sumado a la explotación del recurso hídrico y la sobre-pesca, en directa competencia con las nutrias. La nutrias de cuello es una especie en lato riegos en los humedales de Benin y puede llegar a extingirse si las amenazas actuales se mantienen. Un programa de manejo y conservación sostenible debe ser desarrollado para salvaguardar la especie y su habitat.

Vuelva a la tapa