IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

|

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group Volume 29 Issue 1 Pages 1 - 67 (January 2012) Citation: Quintela, F.M., Da Silva, F.A., Assis, C.L. de and Antunes, V.C. (2012). Data on Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora: Mustelidae) Mortality in Southeast and Southern Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 29 (1): 5 - 8 Data on Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora: Mustelidae) Mortality in Southeast and Southern Brazil Fernando Marques Quintela1, Fabiano Aguiar da Silva2, Clodoaldo Lopes de Assis3 and Vanessa Cardoso Antunes4

11Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Avenida Bento Gonçalves 9.500, Bairro Agronomia, Porto Alegre, RS, CEP 91501-970. e-mail: quintela@gmail.com |

|

| received 13th December 2011, accepted 2nd January 2012 |

| Abstract: Herein we present data on Lontra longicaudis mortality in Minas Gerais (n=12) and Rio Grande do Sul (n=14) states, Southeastern and Southern Brazil, respectively. In Minas Gerais most deaths were caused by entanglement and drowning in fishing gear (n=5; 42%), followed by roadkill (n=3; 25%), dog attack (n=2; 17%), hunting and undetermined cause (n=1; 8% each). In Rio Grande do Sul, the major cause of death was roadkill (n=10; 72%), followed by hunting (n=2; 14%), dog attack and undetermined cause (n=1; 7% each). The habitats associated with the highest number of deaths were reservoirs in Minas Gerais (n=8, 67%) and pluvial channels in Rio Grande do Sul (n=7, 50%). |

| Keywords: Neotropical otter; deaths; roadkill; fishing gear |

| Française | Español |

The neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis Olfers, 1818 is a semi-aquatic mustelid, reaching up to 1.4 m in length and 14 kg of body weight (Emmons and Feer, 1997) and distributed from northeastern Mexico south to Uruguay, Paraguay and across the northern part of Argentina to Buenos Aires province (Larivière, 1999). In the 20th century, hunting for fur caused local extinctions of L. longicaudis populations (Waldemarin and Alvarez, 2008). Loss and fragmentation of habitats, water pollution and conflicts with fisheries also contributed to the species decline and still represent current threats to the remaining populations (Indrusiak and Eizirik, 2003; Waldemarin and Alvarez, 2008; González and Lanfranco, 2010). The species is listed in the IUCN 2011 World Red List as Data Deficient, with a decreasing population trend (Waldemarin and Alvarez, 2008). It is considered Endangered in Argentina (Diaz and Ojeda, 2000), Susceptible in Uruguay (González and Lanfranco, 2010) and Vulnerable in the Brazilian states of São Paulo (PROBIO/SP, 1998), Minas Gerais (Machado et al., 1998), Paraná (Mikich and Bérnils, 2004) and Rio Grande do Sul (Indrusiak and Eizirik, 2003).

In Brazil, most of the studies on L. longicaudis were focused on feeding habits (Passamani and Camargo, 1995; Helder-José and De Andrade, 1997; Pardini, 1998; Colares and Waldemarin, 2000; Quadros and Monteiro-Filho, 2001; Kasper et al., 2004; 2008; Alarcon and Simões-Lopes, 2004; Quintela et al., 2008; Carvalho-Junior et al., 2010) and use of latrines and shelters (Soldateli and Blacher, 1996; Pardini and Trajano, 1999; Waldemarin and Colares, 2000; Quadros and Monteiro-Filho, 2002; Alarcon and Simões-Lopes, 2003; Kasper et al., 2004, 2008; Carvalho-Junior, 2007; Quintela et al., 2011), while data on mortality causes are scarce. Thus, herein we present data on mortality of L. longicaudis in Southeastern and Southern Brazil, aiming to contribute to the species’ conservation.

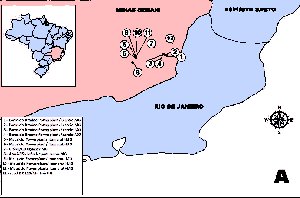

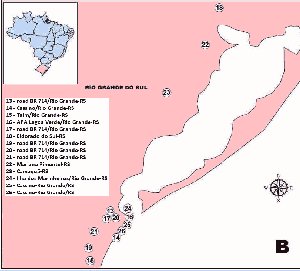

This study was conducted in the States of Minas Gerais and Rio Grande do Sul, Southeastern and Southern Brazil respectively. In Minas Gerais the study area contains rivers and streams of the Paraíba do Sul basin and associated reservoirs, between the counties of Muriaé (21°10'S, 42°22'W) and São João Nepomuceno (21°31'S, 42°54'W), Atlantic Forest biome (Fig. 1). In Rio Grande do Sul, the study area comprises the Internal and External coastal plain geomorphological units, between the counties of Eldorado do Sul (30°01'S, 30°19'W) and Rio Grande (32°15'S, 52°27'W) (Fig. 1).

|

|

| Figure 1. Study area: A) Minas Gerais, B) Rio Grande do Sul. Numbers correspond to deaths shown in Table 1. (click for larger version) | |

Data on L. longicaudis mortality were obtained from March 2008 to August 2011 through field observation and reports from three locals and two collaborating researchers. Well preserved individuals were collected and deposited in mammalian collections of Museu de Ciências Naturais of Universidade Luterana do Brasil, Canoas, Rio Grande do Sul and Museu de Zoologia João Moojen, Viçosa, Minas Gerais.

A total of 26 otter deaths were recorded in the study period, 12 in Minas Gerais and 14 in Rio Grande do Sul. In Minas Gerais the highest number of deaths comprised entanglement and drowning in fishing nets (n=5; 42%), followed by road kill (n=3; 25%) (Fig. 2), dog attack (n=2; 17%), hunting and undetermined cause (n=1; 8% each). In Rio Grande do Sul, the highest number of deaths comprised road kill (n=10; 72%) (Fig. 3), followed by hunting (n=2; 14%), dog attack and undetermined cause (n=1; 7% each) (Table 1).

|

|

| Figure 2. Roadkilled otter in Cataguases Minas Gerais, Southeastern Brazil.. (click for larger version) | Figure 3: Roadkilled otter in Eldorado do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul, Southern Brazil. |

The habitats associated with the highest number of deaths in Minas Gerais were reservoirs (n=8, 67%), followed by rivers (n=3, 25%) and streams (n=1, 8%). In Rio Grande do Sul the highest number of deaths were associated with pluvial channels (n=7, 50%), followed by coastal streams (n=4; 29%), marshes (n=2; 14%) and estuary (n=1; 7%) (Table 1).

Despite the small sample size, we observed differences in major causes of death between the two investigated areas. While roadkill represented the major cause of otter death in Rio Grande do Sul, most of the mortality records in Minas Gerais were related to entanglement and drowning in fishing gear. Absence of records of deaths by accidental captures in fishing nets in Rio Grande do Sul may be related to low density of otters in Patos Lagoon estuary, the system where most of the fishery activity is concentrated in the region.

In coastal streams environments, where otters are more commonly observed, gillnet and fyke net fishery is impractical. On the other hand, gillnet and fyke net fishery activities in Minas Gerais sampled areas are conducted mainly in reservoirs, where otters are commonly observed. Carvalho (2007) considers man to be the otter’s main competitor for food; they have the same preferences for fish species, which results in direct conflict with fishermen as well as deaths by entanglement. Death by entanglement in fishing gear is also documented for Lutra lutra (van Moll, 1988; Foster-Turley et al., 1990; Lodé, 1993; Poole et al., 2007; Hauer et al., 2002; Georgiev, 2007) and Lontra felina (Pizarro Neyra 2008). In western France, Lodé (1993) considered accidental drowning in fyke nets to be the major cause of L. lutra deaths.

Lontra longicaudis roadkill have been observed in the states of São Paulo (Freitas et al., 2009), Mato Grosso do Sul (Cáceres et al., 2010), Santa Catarina (Cherem et al., 2007) and Rio Grande do Sul (Hengemühle and Cadermatori, 2008; Bager and Rosa, 2010) and represent the only documented mortality data on the species in Brazil. In Rio Grande do Sul Coastal Plain most federal and state highways and even local roads are bordered by pluvial channels, which are suitable habitats for otter occurrence. The movement of otters between pluvial channels by crossing highways and roads is the main cause of otter road kill. Hauer et al. (2002) found traffic accidents to be the major cause of mortality of L. lutra in eastern Germany. Philcox et al. (1999) also observed that 91% of 673 L. lutra roadkills occurred at points where roads cross watercourses.

Hunting and dog attacks represented minor causes of death in the present study. Lontra longicaudis was hunted excessively for the pelt trade in the period 1950-1970 and illegal hunting is still practiced (Waldemarin and Alvarez, 2008). It is important to note that hunting in the studied areas is related to fishery conflicts, with the justification that they are competitors for fish and damage fishing gear. The meat was not consumed from any of the three killed individuals while the pelt was removed from only one. Domestic and feral dogs are a potential threat to wild mammals, especially when organized in packs (Galetti and Sazima, 2006). Deaths by dog attacks were also reported in low proportions for L. lutra in Central Finland (Skarén, 1992) and southern Bulgaria (Georgiev, 2007) and for Lontra felina in southern Peru (Pizarro Neyra, 2008).

In the present study we did not detect and investigate deaths caused by diseases, intoxication or poisoning. In our informal interviews with local people no one admitted to using poisoned carcasses aimed at killing otters. However, incidental otter deaths may occur due to poisoning campaigns targeting pests of crops or livestock, such as rodents, canids and felids, and these should also be investigated. Lodé (1993) found that reduction in L. lutra distribution in western France coincided with poisoning campaigns against muskrats and coypus.

Organochlorine compounds have often been found in L. lutra (Mason et al., 1986; 1992), Lontra canadensis (Stansley et al., 2010) and Enhydra lutris samples (Nakata et al., 1998; Bacon et al., 1999). In southern Rio Grande do Sul there are extensive rice crops adjacent to swamps, shallow lakes, pluvial channels and other otter habitats. Rice crops receive large pesticide applications, and bioaccumulation in adjacent otter habitats represents a poisoning risk (Pastor et al. 2004).

The present study contributes to knowledge on L. longicaudis mortality in South and Southeastern Brazil. Considering the observed results, we recommend: assessment of locations where multiple otter road kill have occured and evaluation of possible mitigation measures (i.e. underground passages); implementation of environmental education activities emphasizing the ecological importance of otter and modifications to fishing gears to prevent accidental deaths; control of domestic and feral dogs in otter habitats. It is also recommended that ecotoxicological studies of aquatic systems adjacent to intensive rice farming be conducted.

REFERENCES

Alarcon, G.G., Simões-Lopes, P.C. (2003). Preserved versus degraded coastal environments: A case study of the neotropical otter in the Environmental Protection Area of Anhatomirim, southestern Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bul. 20(1):6-18.

Alarcon, G.G., Simões-Lopes, P.C. (2004). The Neotropical Otter Lontra Longicaudis feeding habits in a marine coastal area, Southern Brazil . IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 21(1): 24 – 30.

Bacon, C.E., Jarman, W.M., Estes, J.A., Simon, M. (1999). Comparison of organochlorine contaminants among sea otter (Enhydra lutris) populations in California and Alaska. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 18(3): 452-458.

Bager, A., Rosa, C.A. (2010). Priority ranking of Road sites for mitigating wildlife roadkill. Biota Neotrop. 10(4): 149-159.

Cáceres, N.C., Hannibal, H., Freitas, D.R., Silva, E.L., Roman, C., Casella, J. (2010). Mammal occurrence and roadkill in two adjacent ecoregions (Atlantic Forest and Cerrado) in south-western Brazil. Zoologia 27(5): 709-717.

Carvalho-Júnior, O. (2007). No rastro da lontra brasileira. Bernúncia, Florianópolis.

Carvalho-Junior, O., Birolo, A.B., Macedo-Soares, L.C.P. (2010). Ecological aspects of neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis) in Peri Lagoon, South Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 27(2): 105-115.

Cherem, J.J., Kammers, M., Ghizoni-Jr, I.V., Martins A. (2007). Mamíferos de médio e grande porte atropelados em rodovias do Estado de Santa Catarina, sul do Brasil. Biotemas 20(3): 81-96.

Colares, E.P., Waldemarin, H. F. (2000). Feeding of the neotropical river otter (Lontra longicaudis) in a coastal region of the Rio Grande do Sul State, Southern Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 17, 6-13.

Díaz, G.B., Ojeda, R.A. (2000). Libro rojo de los mamíferos amenazados de la Argentina. Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos, Mendoza.

Emmons, L.H, Feer, F. (1997). Neotropical rainforest mammals: A field guide. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Foster-Turley, P., MacDonald, S.M. & Mason, C.F. (1990) Otters: an action plan for their conservation. IUCN/Otter Specialist Group. Gland, Switzerland.

Freitas, C.H. (2009). Atropelamentos de vertebrados nas rodovias MG-428 e SP-334 com análises dos fatores condicionantes e valoração econômica da fauna. Ph.D.Thesis. Universidade Estadual Paulista Júlio Mesquita Filho, Rio Claro, São Paulo, Brasil.

Galleti, M., Sazima, I. (2006). Impacto de cães ferais em um fragmento urbano de Floresta Atlântica no sudeste do Brasil. Natureza & Conservação 4(1): 58-63.

Georgiev, D.G. (2007). Otter (Lutra lutra L.) mortalities in southern Bulgaria: a case study. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 24(1): 36-40.

González, E.M., Lanfranco, J.A.M. (2010). Mamíferos de Uruguay. Guia de campo e introducción a su estúdio y conservación. Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Vida Silvestre Uruguay, Montevideo.

Hauer, S., Ansorge, H., Zinke, O. (2002). Mortality patterns of otters (Lutra lutra) from eastern Germany. J. Zool. 256: 361-368.

Helder-José, De Andrade, H.K. (1997). Food and feeding habits of neotropical river otter Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora, Mustelidae). Mammalia 61:193-203.

Hengemühle, A., Cademartori, C.V. (2008). Levantamento de mortes de animais silvestres devido a atropelamento em um trecho da Estrada do Mar (RS-389). Biodivers. Pampeana 6(2): 4-10.

Indrusiak, C., Eizirik, E. (2003). Carnívoros. In: Fontana, C.S., Bencke, G.A., Reis, R.E. (Eds.) Livro Vermelho da Fauna Ameaçada de Extinção no Rio Grande do Sul. Edipucrs, Porto Alegre, Brazil, pp. 507-534.

Kasper, C.B., Bastazini, V.A.G., Salvi, J., Grillo, H.C.Z. (2008). Trophic ecology and the use of shelters and latrines by the Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis) in the Taquari Valley, Southern Brazil. Iheringia, Ser. Zool. 98(4): 469-474.

Kasper, C.B., Feldens, M.J., Salvi, J., Grillo, H.C.J. (2004). Estudo Preliminar sobre a ecologia de Lontra longicaudis no Vale do Taquari, Sul do Brasil. Rev. Bras. Zool. 21(1): 65-72.

Kinlaw, A. (2004). High mortality of Neartic river otters on a Florida, USA Interstate Highway during an extreme drought. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 21(2): 76-88.

Larivière, S. (1999). Lontra longicaudis. Mammal. Species 609: 1-5.

Lodé, T. (1993). The decline of otter Lutra lutra populations in the region of the Pays de Lorie, Western France. Biol. Cons. 65: 9-13.

Machado, A.B.M., Fonseca, G.A.B., Machado, R.B., Aguiar, L.M.S., Lins, L.V. (1998). Livro vermelho das espécies ameaçadas de extinção da fauna de Minas Gerais. Fundação Biodiversitas, Belo Horizonte.

Mason, C.F., Ford, T.C., Last, N.I. (1986). Organochlorine Residues in British Otters. Bull. Env. Contam. Toxicol. 36: 656 – 661

Mason, C.F., MacDonald, S.M., Bland, H.C., Ratford, J. (1992). Organochlorine pesticide and PCB contents in otter (Lutra lutra) scats from western Scotland. Water, Air and Soil Pollut. 64: 617-626.

Mikich, S.B., Bérnils, R.S. (2004). Livro vermelho da fauna ameaçada de extinção do Estado do Paraná. Governo do Paraná, Curitiba.

Nakata, H., Jing, L., Tanabe, S., Kannan, K., Giesy, J.P., Thomas, N. (1998). Accumulation patterns of organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls in southern sea otters (Enhydra lutris nereis) found stranded along coastal California, USA. (1998). Environ. Pollut. 103(1): 45-53.

Pardini, R. (1998). Feeding ecology of the neotropical river otter Lontra longicaudis in an Atlantic Forest stream, south-eastern Brazil. J. Zool., 245,385-391.

Pardini, R., Trajano, E. (1999). Use of shelters by the neotropical river otter (Lontra longicaudis) in an Atlantic Forest stream, Southeastern Brazil. J. Mammal. 80(2):600-610.

Passamani, M., Camargo, S.L. (1995). Diet of the river otter Lutra longicaudis in Furnas Reservoir, south-eastern Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 12: 32-34

Pastor, D., Sanpera, C., González-Solis, J., Ruiz, X, Albaigés, J. (2004). Factors affecting the organochlorine pollutant load in biota of a rice field ecosystem (Ebro Delta, NE Spain). Chemosphere 55(4): 567-576.

Philcox, C.K., Grogan, A.L., MacDonald, D.W. (1999). Patterns of otter Lutra lutra road mortality in Britain. J. Applied Ecol. 35: 748-762.

Pizarro Neyra, J. (2008). Mortallity of the marine otter (Lontra felina) in Southern Peru. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 25(2): 94-99.

Poole, W.R., Rogan, G. & Mullen, A. (2007) Investigation into the impact of fyke nets on otter populations in Ireland. Irish Wildlife Manuals No. 27. National Parks & Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage & Local Government. Dublin, Ireland. http://www.npws.ie/publications/irishwildlifemanuals/

PROBIO/SP (1998). Fauna ameaçada no Estado de São Paulo. Secretaria de Estado do Meio Ambiente, SMA/CED, São Paulo.

Quadros, J., Monteiro-Filho, E.L.A. (2001) Diet of the neotropical otter, Lutra longicaudis, in an Atlantic Forest area, Santa Catarina State, Brazil. Stud. Neotrop. Fauna Environm. 36(1): 15-21.

Quadros, J., Monteiro-Filho, E.L.A. (2002). Sprainting sites of the neotropical otter, Lontra longicaudis, in an Atlantic Forest area of southern Brazil. Mast. Neotrop. 9(1): 39-46.

Quintela, F.M., Ibarra, C., Colares, E.P. (2011). Utilização de abrigos e latrinas por Lontra longicaudis (Olofers, 1818) em um arroio costeiro na Área de Proteção Ambiental da Lagoa Verde, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Neotrop. Biol. Cons. 6(1): 35-43.

Quintela, F.M., Porciuncula, R.A., Colares, E.P. (2008). Dieta de Lontra longicaudis (Olfers) (Carnivora, Mustelidae) em um arroio costeiro da região sul do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Neotrop. Biol. Cons. 3(3): 119-125.

Skarén, U. (1992) Analysis of One Hundred Otters Killed by Accidents in Central Finland. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 7: 9 – 12.

Soldateli, M., Blacher, C. (1996). Considerações preliminares sobre o número e distribuição espaço/temporal de sinais de Lutra longicaudis (Olfers, 1818) (Carnivora: Mustelidae) nas lagoas da Conceição e do Peri, Ilha de Santa Catarina, SC, Brasil. Biotemas, 9:38-64.

Stansley, W., Velinsky, D., Thomas, R. (2010). Mercury and halogenated organic contaminants in river otters (Lontra canadensis) in New Jersey, USA. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 29(10): 2235-2242.

van Moll, G.C.M. (1988). Causes of Otter Mortality in the Netherlands between 1963 and 1987. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 3: 9

Waldemarin, H.F., Alvarez, R. (2008). Lontra longicaudis. In: IUCN 2011 Red List of Threatened Species. Accessible on: <http://www.iucnredlist.org/>

Waldemarin, H.F., Colares, E.P. (2000). Utilization of resting sites and dens by the neotropical river otter (Lontra longicaudis) in the south of the Rio Grande do Sul State, Southern Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 17(1):14-19.

Résumé : Donnees de Mortalite sur Lontra longicaudis (Carnivore: Mustelides) dans le Sud-Est et le Sud du Bresil

Ici, nous présentons des données sur la mortalité de Lontra longicaudis dans l’état fédéral de Minas Gerais (n=12) et de Rio Grande do Sul (n=14) respectivement au sud-est et sud du Brésil. Dans l’état de Minas Gerais, la plupart des décès ont été causés par la prise accidentelle et la noyade dans les filets (n=5; 42%), suivis par les collisions routières (n=3; 25%), les attaques de chiens (n=2; 17%), la chasse et les causes indéterminées (n=1, 8% chacun). Dans le Rio Grande do Sul, la cause majeure de décès a été Roadkill (n=10; 72%), suivie par la chasse (n=2; 14%), attaque de chien et de cause indéterminée (n = 1 chacun, 7%). Les habitats associés au plus grand nombre de décès sont les retenues d’eau dans l’état de Minas Gerais (n=8, 67%) et les canaux pluviaux dans l’état du Rio Grande do Sul (n=7, 50%).

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Dados sobre Mortalidade de Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora: Mustelidae) no Sudeste e Sul do Brasil

Apresentamos dados sobre a mortalidade de Lontra longicaudis nos estados de Minas Gerais (n=12) e Rio Grande do Sul (n=14), Sudeste e Sul do Brasil, respectivamente. Em Minas Gerais a maioria das mortes foi causada por enredamento e afogamento em redes de pesca (n=5; 42%), seguido por atropelamento (n=3; 25%), ataque de cães (n=2; 17%), caça e causa indeterminada (n=1; 8% each). No Rio Grande do Sul, a maior causa de morte foi atropelamento (n=10; 72%), seguido por caça (n=2; 14%), ataque de cães e causa indeterminada (n=1; 7% each). Os habitats associados ao maior número de mortes foram reservatórios em Minas Gerais (n=8, 67%) e canais pluviais no Rio Grande do Sul (n=7, 50%).

Vuelva a la tapa