IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

|

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group Volume 30 Issue 2 (October 2013) Citation: Carvalho-Junior, O., Macedo-Soare, L., Bez Birolo, A. and Snyder, T. (2013). A Comparative Diet Analysis of the Neotropical Otter in Santa Catarina Island, Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 30 (2): 67 - 77 A Comparative Diet Analysis of the Neotropical Otter in Santa Catarina Island, Brazil Oldemar Carvalho-Junior1, Luis Macedo-Soare2, Alesandra Bez Birolo1 and Tammy Snyder3

1Instituto Ekko Brasil, Servidão Euclides João Alves, S/N, Lagoa do Peri, 88066-000, Florianópolis, SC, Brazil.

email: atendimento@ekkobrasil.org.br |

|

|

| Received 9th May 2013, accepted 17th August 2013 |

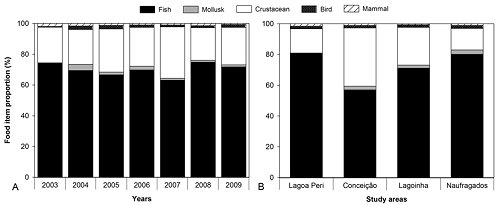

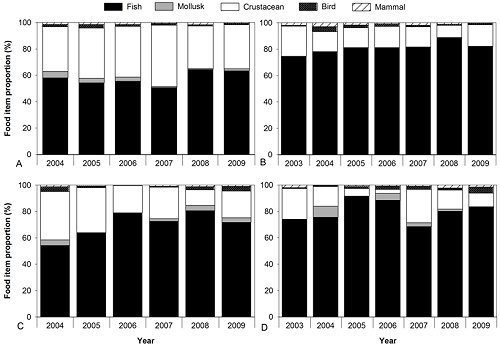

| Abstract: This work represents a comparative diet analysis of the neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis by scat analysis (n= 8841) for four different areas, located on Santa Catarina Island, south of Brazil. The study areas, the main ecosystems found on the Island, are all natural reserves. The results are based on long term data sets (2003-2009) comparing food item proportions through years, with inter-annual and monthly variability. For all study areas, fish (71%) and crustacean (25%) are the main food types, followed by mollusks (2%), birds (1%) and mammals (1%). In the case of main food categories, there is no observed inter-annual or monthly variability for the food items that compose the otter’s diet. The results show that, on the Santa Catarina Island, the neotropical otter presents a well defined diet composition that does not change from place to place, and has no inter-annual or monthly variability. |

| Keywords: Lontra longicaudis, spraint analysis, habitats. |

| Française | Español | Português |

INTRODUCTION

Lontra longicaudis is a semi-aquatic carnivorous mammal that belongs to the Mustelidae Family and Lutrinae Subfamily (Wilson and Reeder, 2005). The species is considered critically endangered by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna e Flora (CITES) and U.S. Endangered Species Act (U.S.E.S.A) (Emmons, 1997; Wilson and Reeder, 2005), and Data Deficient by the IUCN (Wilson and Reeder, 2005). In Brazil, the Fauna Protection Law that prohibits the commerce of products made from animals protects the otter. The species was recently considered endangered in the Atlantic Forest, according to the last meeting of Brazilian specialists at Iperó, São Paulo, organized by ICMBio (Chico Mendes Institute for the Biodiversity – Federal Environmental Agency).

In Brazil, the neotropical otter is threatened due to various reasons, such as destruction of aquatic and riparian habitat, reduction of the otters’ fishing and relaxation areas, hunting promoted by farmers, fishermen and aquaculture, and the presence of domestic animals such as dogs (Serfass et al., 1995; Stickney and McVey 2002; Adámek et al., 2003; Kloskowski 2005; Boyle 2006; Park et al., 2007). Neotropical otters are not popular with fishermen and aquacultures, for example, who claim that otters are prejudicial; damaging nets, eating cultivated fishes, and impacting mussel and oyster farms (Alarcon and Simões-Lopes, 2004; Trindade, 1991).

Neotropical otter conservation along the coastal region of Santa Catarina state is dependent upon on the conservation of the Atlantic Rain Forest, currently endangered by human activities. Stratification of the forest, along with the high density of epiphytes represents an important contribution to the formation of safe environments for the Lontra longicaudis (Carvalho-Junior et al., 2006). The main threat for the otter is fragmentation of the environment. Fragmentation results in a mosaic of patches with increasing threat to otter conservation as the distance between patches increases. Neotropical otters are constantly moving from place to place and they need trustable ecological corridors to complete a safe journey (Carvalho-Junior, 2007). A second threat is the presence of domestic dogs in the study area. Domestic dogs walk freely along the lake and channels, representing a serious threat as they can transmit diseases as well as chasing and killing wild animals, including otters (Serfass et al., 1995; Boyle, 2006; Park et al., 2007).

Distribution of the neotropical otter is based on scarce and sparse data which results in lack of information about the neotropical otter’s natural life. According to Emmons (1997) the neotropical otter can be found in Central and South America, from Mexico south to Uruguay and up to 3.000 m elevation. In South America the species is registered for Argentina, Belize, Brazil, Columbia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela (Wilson and Reeder, 2005).

In Santa Catarina State, Lontra longicaudis can be found from the highlands (to 1.200 m) to the coast, forests, rivers, lakes and costal islands (Quadros and Monteiro-Filho, 2001; Alarcon and Simões-Lopes, 2004; Carvalho-Junior et al., 2010a,b).

A great majority of the works related to Lontra longicaudis confirm that the otter’s diet in Brazil is formed mainly by fish and crustaceans (Uchôa et al., 2004; Quadros and Monteiro-Filho, 2001; Quintela et al., 2008; Rheingantz et al., 2011). Uchôa et al. (2004), in the Reserva Natural Salto Morato (São Paulo) found that 72% of the neotropical otter’s diet consists of fish, crab and shrimp. Quadros and Monteiro Filho (2000), found that, for the Volta Velha Reserve (SC), the most consumed prey are fish (74.26%) and crustaceans (62.87%). Also Pardini (1998), at the Betari River, a Touristic State Park - Ribeira Valley (SP), found that fish (93%), crustaceans (72.4%) and insects (21%) were the main items in the otter’s diet. Quintela et al. (2008) studying a coastal stream in Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil, define the diet of the species as fish (82,6%), followed by crustaceans (20,6%), birds (4,5%), mammals and snakes (3,7% each), coleoptera (1,2%), amphibians (0.8%) and gastropod mollusks and belostomatídeos (0.4% each).

Studies related to diet composition of otters in the Santa Catarina Island (Florianópolis) were performed previously (Carvalho-Junior et al, 2010a). A previous study conducted at Conceição Lagoon reveals that fish and crustacean are the main food items, followed by mollusks, birds and mammals, showing no inter-annual or monthly variability. Another study performed at Peri Lagoon found similar results (Carvalho-Junior et al., 2010b).

However, a comparative work at the same time, for different areas, had not been previously attempted. The purpose of this work is to compare the neotropical otter’s diet composition in four different study areas of Santa Catarina Island, in the south of Brazil, describing possible differences through annual and inter-annual diet composition.

The diet is perhaps the most studied aspect of the neotropical otter, due to the facility of data collection and analysis of excrements. Nevertheless, authors seem to disagree on the facts as to whether the species is opportunist or specialist. For example, for Chanin (1985), otters are considered opportunistic predators due to their plasticity when feeding in different environments. Moreover, Kruuk (1995), using Kendall's Coefficient of Concordance, states that the river otter is one of the most specialized animals. The results presented here could be important to help to clarify this matter.

STUDY AREA

|

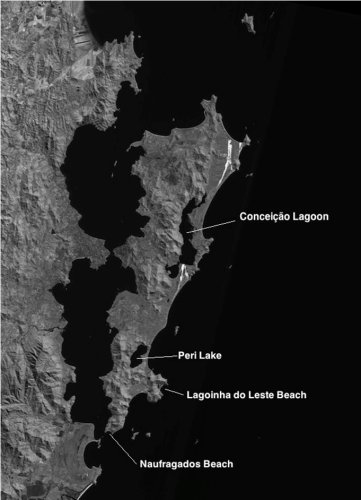

| Figure 1. Study areas located in Santa Catarina Island, South of Brazil: Conceição Lagoon, Peri Lake, Lagoinha do Leste Beach and Naufragados Beach. (click for larger version) |

Santa Catarina Island (Figure 1) represents the largest island of the Santa Catarina State, located parallel to the mainland and separated by a narrow channel (Carvalho-Junior et al., 2012). It has an average length of 54 km and width average of 18 km. Bays, promontories, smaller islands and lagoons are common features in the study area. The most important water bodies in the Santa Catarina Island are the Peri Lake (5,1 km2) and Conceição Lagoon (19,71 km2). A study related to the distribution and characteristics of environments used by the neotropical otter in the coastal region of Santa Catarina state (Carvalho-Junior et al., 2004a) and in the south of Santa Catarina Island (Carvalho-Junior et al., 2004b), pointed out the importance of the indented coastline for the Lontra longicaudis.

METHODS

Between 2003 and 2009, spraints were collected monthly in four areas of Santa Catarina Island: Lagoa do Peri, Naufragados Beach, Lagoa da Conceição and Lagoinha do Leste Beach (Figure 1). The study areas were covered using canoes and kayaks. Fecal samples were collected and placed individually in small plastic bags and stored in a refrigerator. In the lab, each sample was washed through a mesh and the undigested remains analyzed under a stereomicroscope. Diet composition was determined from a total of 8.841 fecal samples and expressed as percentage relative frequency of occurrence (RF%).

The chi-squared was used (Zar, 1996) to test the variation of food items among years and areas. When any significant differences were found, Tukey HSD for unequal sample sizes was performed to detect which means were responsible for the difference with a 0.05 level of probability. Raw proportion diet composition data were arcsine square root transformed when the Tukey test was performed (Zar, 1996). Tukey test is applied when the null hypothesis is rejected.

Due to the size of the database, the data tend to a normal distribution. Therefore, the ANOVA is applied because it is much more robust than a nonparametric test, even when the data do not present a classic and perfect normal distribution. In this case, a test like ANOVA can indeed provide a reliable result, given the sample size.

Unifactorial Analysis of Variance (1-way ANOVA) was applied to test for variation in the number of faeces found in different years and months, for each study area and for Santa Catarina Island. Bartlett’s test was used to verify the homogeneity of variances, while post-hoc Tukey’s tests were used to explain differences found by ANOVA. All data were [log10(x+1)] transformed in order to stabilize the variance and fit the data to a normal distribution (Zar, 1996). The relationship between the number of faeces and the number of the food item fish found in the samples was tested with the Pearson correlation index (Zar, 1996). All tests were performed by Statistica 7.0 (Statsoft Inc. 1984-2004).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

From the results we can recognize different prey categories, such as fish, crustacean, mollusk, bird and mammal. In the study period, fish (71%) and crustaceans (25%) were the main food items of otters in all study areas and years (Figures 2 and 3), followed by mollusks (2%), birds (1%) and mammals (1%). The results show that neotropical otters in the study area feed mainly on fishes, followed by crustaceans.

There is no observed inter-annual or monthly variability for the food items that compose the otter’s diet. On the whole, in Santa Catarina Island, no difference emerged in the %RF of the main food items among years (Table 1), while significant differences were found for fish and crustaceans among study areas (Table 1). However, the preference for the main food items was always the same, being fish (first) and crustacean (second). Proportionally, the smallest occurrence of fish in the diet was found for Lagoa da Conceição, where otter predation on crustaceans was also the highest.

This might be reflective of the fact that Lagoa da Conceição has the influence of the sea. Consequently, compared to Lagoa do Peri, there is a higher biodiversity in the area and wider availability of prey (Carvalho-Junior et al., 2010a). Lagoa do Peri is a fresh water lake, with a narrower range of potential prey (Carvalho-Junior et al., 2010b). Therefore, important aspects to be considered are food availability and water quality (Kruuk et al., 1991; Kruuk, 1995; Chanin, 2003). Fish species predated by the neotropical otter might change according to abundance, habitat and seasonality (Kruuk, 2006), as well as ecosystem productivity.

When testing for variation among years for each study area, the proportion of fish at Lagoinha do Leste was significantly higher (P<0,05) in 2008, while that of crustacean was higher in 2004, when fish occurrence was the lowest (Table 1). In Naufragados Beach, significant variation occurred for fish, mollusks and crustacean.

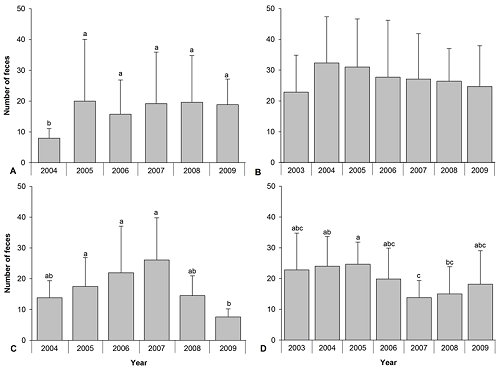

Perhaps, in the case of lack of fish, the otter could change the proportion of crustaceans in the diet. In fact, studies at Lagoa da Conceição show that the crustacean is relatively more important when compared to other areas as Lagoa do Peri (Carvalho-Junior et al., 2006). As the diet composition is obtained from faeces, number of faeces can also be important to the analysis (Figure 4).

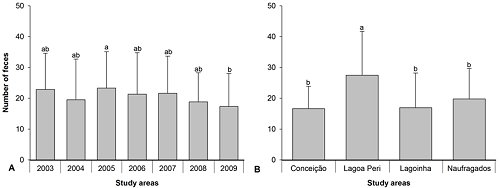

According to the ANOVA, the number of faeces are different between years for Lagoa da Conceição (F=14.229; P<0.001), Lagoinha do Leste Beach (F=6.845; P<0.001) and Naufragados Beach (F=2.319; P=0.0413) (Figure 4). At Lagoa do Peri, the number of faeces did not show any difference between years (F=0.664; P=0.6789) (Fig. 4B). At Lagoa da Conceição a smaller amount of faeces is found in 2004 (Figure 4A) while in Lagoinha do Leste, 2009 presented the lowest amount (Figure 4C). For Naufragados Beach, 2005 was the peak (P<0.05) of number of faeces with 2007 registering the minimum (Figure 4D). Differences between years for number of faeces might be suggesting that the number of otters varies with time at Lagoa da Conceição, Lagoinha do Leste and Naufragados Beach.

Lagoa da Conceição represents the largest water body ecosystem in the island. Its contact to the ocean is reflected in the seasonal and interannual variation of fish and crustacean stock (Ribeiro et al., 1997a; Ribeiro et al., 1997b). This could affect the distribution of otters through months and years. On the other hand, Lagoinha do Leste and Naufragados beach are the smallest water bodies. Their water levels are highly influenced by precipitation, opening or closing the access channels to the ocean. Therefore, biomass of preys can be highly affected by this dynamic, influencing also on the neotropical otter presence. These last two areas might be more important as a support to the otter’s movement from one region to another.

On the other hand, Lagoa do Peri is a fresh water lagoon, connected to the ocean through a channel but not influenced by sea water. The lagoon is 3 meters above sea level and the channel is 4.5 km long, running parallel to the coastline. The fish population at this ecosystem is more stable and homogenous, composed mainly by Cichlidaes, when compared to Lagoa da Conceição. In fact, 90% of the fish consumed by neotropical otters in the area are Cichlidaes (Carvalho-Junior et al, 2010a). The only crustacean in the lagoon is the fresh-water-lobster (Macrobrachium sp.).

For Santa Catarina Island, 1-way ANOVA resulted in differences between years for number of faeces (F=2.172; p=0.0457) and between areas (F=13.942; P<0.001). 2005 is the year with the highest number of faeces collected (P<0.05) (Figure 5A), as well as for Lagoa de Peri (Figure 5B).

|

| Figure 5. Distribution of number of faeces (mean±sd) through (A) years 2003 (only for Lagoa do Peri and Naufragados beach) to 2009, and (B) in the different study areas. (click for larger version) |

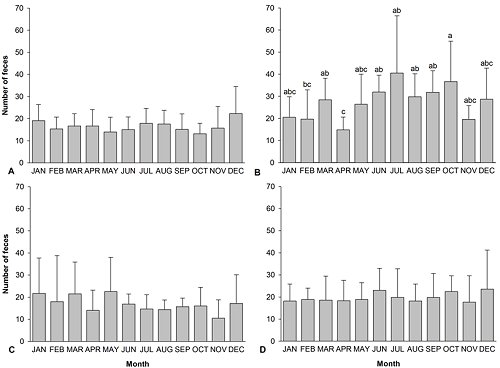

When monthly distribution of number of faeces was analyzed in each study area, no significant (P>0.05) differences were found for Lagoa da Conceição (F=0.551; P=0.859), Lagoinha do Leste Beach (F=0.504; P=0.893) and Naufragados Beach (F=0.262; P=0.991) (Figure 6). In Lagoa do Peri number of faeces is larger (F=2.018; P=0.039) in October and smaller in April (Figure 6B). On the other hand, when grouping the data and considering Santa Catarina Island, number of faeces does not change between months (F=1.232; P=0.265).

Lagoa do Peri is a fresh water lake, near the ocean, well protected, surrounded by Atlantic Forest and with 8 shelters available (Carvalho-Junior, 2007). The larger number of faeces could be an indication of habitat preference by the Lontra longicaudis. This area might represent a hot spot, important for the survival of the neotropical otter population in the Santa Catarina Island. On the other hand, the stable number of spraints along the year through the study areas suggests that the population is well distributed or mixed.

Establishing a relation between number of spraints and otters population size is a difficult task (Kruuk, 2006). Spraints can be washed by rain or tide, otters might defecate on land more times than in the water during winter, or defecate in areas of difficult access. However, if there are spraints it means there are otters. On the other hand, the absence of spraints does not really mean that there are no otters in the area. In the present case the survey was performed for a long period of time (8 years). As a consequence, the discrepancy between averages tends to be lower.

The results give a good idea of the neotropical otter’s diet on the Santa Catarina Island and can contribute to the discussion of the neotropical otter being specialist or opportunist. It also raises questions about the connection between ecosystems and how the neotropical otter population is geographically organized. The conservation of the species depends on the knowledge we have about it. Diet composition can help us to find out how sensitive and what is the adaptive capacity of the neotropical otter to environmental changes due to habitat loss, over exploitation, invasive species and climate change.

Acknowledgements - This work is sponsored by Petrobras, trough Petrobras Environmental Program (Programa Petrobras Ambiental) and supported by FLORAM (Fundação Municipal do Meio Ambiente de Florianópolis) and IBAMA (Instituto Brasileiro de Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis). We would like to acknowledge Marcelo Tosatti for helping with the fieldwork. We also thank the staff of the State Protection Environmental Police “Dr. Fritz Muller” at the Rio Vermelho State Park for their assistance and all ecovolunteers that participated in the field, and to Sandra Quiñones Herce for translating the abstract to Spanish.

REFERENCES

Adámek Z., Kortan D., Lepic P., Andreji J. (2003). Impacts of otter (Lutra lutra L.) predation on fishponds: A study of fish remains at ponds in the Czech Republic. Aquaculture International. 11(4): 389-396.

Alarcon, G.G., Simões-Lopes, P.C. (2004). The Neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis feeding habits in a marine coastal area, Southern Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull., 21(1): 24-30.

Boyle, S. (2006). North American river otter (Lontra canadensis): a technical conservation assessment. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region.

[Available from http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/ assessments/northamericanriverotter.pdf Accessed 20.08.2010].

Carvalho-Junior, O., Banevicius, N.M.S., Mafra, E.O. (2006). Distribution and caracterization of environments used by otters. Journal of Coastal Research, 39: 1087-1089.

Carvalho-Junior, O.; Fillipini, A.; Salvador, C. (2012). Distribution of neotropical otter, Lontra longicaudis (Olfers, 1818) (Mustelidae) in coastal islands of Santa Catarina, Southern Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull., 29(2): 95–108.

Carvalho-Junior O., Birolo A.B., Macedo-Soares L.C.P. (2010a). Ecological aspects of Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis) in Peri Lagoon, South Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull., 27(2): 105-115.

Carvalho-Junior O., Macedo-Soares L.C.P., Birolo A.B. (2010b). Annual and interannual food habits variability of a Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis) population in Conceição Lagoon, South of Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull., 27(1): 24–32.

Carvalho-Junior, O. (2007). No Rastro da Lontra Brasileira. Ed. Bernuncia, Florianópolis, Brasil, 112pp.

Carvalho-Junior, O. (2004a). Spatial organization of river otter Lontra longicaudis in the south of Santa Catarina Island, Brazil. Proceedings of the 11 Reunión de Trabajo de Especialistas en Mamíferos Acuáticos de America del Sur. Quito: NAZCA, p. 63.

Carvalho-Junior, O., Banevicius, N.M.S., Mafra, E.O. (2004b). Distribution and characterization of environments used by otters in the coastal region of Santa Catarina State, Brazil. Journal of Coastal Research, 39: 1087-1089.

Chanin P. (1985). The Natural History of Otters, Elsevier, London.

Chanin P. (2003). Ecology of the European Otter. Conserving Natura 2000 Rivers. Ecology Series 10.

Emmons, L. (1997). Neotropical rainforest mammals: a field guide. 2nd ed. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 307p.

Kloskowski J. (2005). Otter Lutra lutra damage at farmed fisheries in southeastern Poland, I: an interview survey. Wildlife Biology, 11(3): 201-206.

Kruuk H., Conroy J.W.H., Moorhouse A. (1991). Recruitment to a population of otters (Lutra lutra) in Shetland, in Relation to Fish Abundance. Journal of Applied Ecology, 28(1): 95-101.

Kruuk H. (1995). Wild Otters. Predation and Populations. Oxford University Press, New York.

Kruuk H. (2006). Otters. Ecology, Behaviour and Conservation. Oxford University Press, New York.

Pardini, R. (1998). Feeding ecology of the neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis in an Atlantic forest stream, south Brazil. J. Zool. London, 245: 385-391.

Park, N.Y., Lee, M.C., Kurkure, N.V., Cho, H.S. (2007). Canine adenovirus type 1 infection of a Eurasian river otter (Lutra lutra). Vet. Pathol, 44:4.

Quadros J., Monteiro-Filho E.L.A. (2000). Fruit occurrence in the diet of the Neotropical otter, Lontra longicaudis, in the Southern Brazilian Atlantic Forest and its implication for seed dispersion. I. J. Neotrop. Mammal, 7(1): 33-36.

Quadros J., Monteiro-Filho E.L.A. (2001). Diet of the Neotropical otter, Lontra longicaudis, in the Atlantic Forest, Santa Catarina State, Southern Brazil. Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment, 36(1): 15-21.

Quintela, F.M., Porciúncula, R.A., Colares, E.P. (2008). Diet of Lontra longicaudis (Olfers) in a coastal stream in southern Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil. Neotrop. Biol. Cons., 3(3): 119-125.

Rheingantz, M.L., Waldemarin, H.F.; Rodrigues, L., Moulton, T. (2011). Seasonal and spatial differences in feeding habits of the Neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora: Mustelidae) in a coastal catchment of southeastern Brazil. Zoologia, 28 (1): 37–44.

Ribeiro, G.C., Clezar, L., Hostim-Silva, M., Filomeno, M.J.B., Aguiar, J.B.S. (1997a). Ictiofauna da Lagoa da Conceição e área costeira adjacente, Ilha de Santa Catarina, SC, Brasil. In: Gestion de La Zone Littorale L’ile de Santa Catarina (Bresil), Publication Du Departement de Geologie et Oceanographie URA CNRS 197, Universite de Bordeaux 1, Aquitaine Ocean (3): 275-280.

Ribeiro, G.C., Clezar, L., Hostim-Silva, M. (1997b). Abundância e distribuição espaço-temporal dos Gerreidae (pisces) na Lagoa da Conceição e área adjacente, Ilha de Santa Catarina, SC, Brasil. In: Gestion de La Zone Littorale L’ile de Santa Catarina (Bresil), Publication Du Departement de Geologie et Oceanographie URA CNRS 197, Universite de Bordeaux 1, Aquitaine Ocean (3): 281-286.

Serfass, T.L., Whary, M.T., Peper, R. L., Brooks, R.P., Swimley, T.J., Lawrence, W.R., Rupprecht, C.E. (1995). Rabies in a river otter (Lutra canadensis) intended for reintroduction. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 26(2): 311-314.

Stickney R.R., McVey J.P. (2002). Responsible Marine Aquaculture. World Aquaculture Society, CABI Publishing, USA.

Trindade, A. (1991). Fish Farming and Otters in Portugal. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull., 6: 7-9.

Uchôa, T., Vidolin, G.P., Fernandes, T.M., Velastin, G.O., Mangini, P.R. (2004). Aspectos ecológicos e sanitários da lontra (Lontra longicaudis OLFERS, 1818) na Reserva Natural Salto Morato, Guaraqueçaba, Paraná, Brasil. Cad. Biodivers., 4(2): 19-28.

Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (2005). Mammal species of the world: a taxonomic and geographic reference. 3rd ed. The Johns Hopkins University Press, V. 1, 743p.

Zar J. H. (1996). Biostatistical analysis. 3 ed. Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

Résumé : Analyse Comparative du Regime Alimentaire de la Loutre à Longue Queue sur l'Ile Santa Catarina, Bresil

Ce travail présente l'étude comparative du régime alimentaire de la Loutre à Longue Queue Lontra longicaudis grâce à l'analyse de ses excréments (n = 8841) dans quatre zones géographiques différentes sur l'île de Santa Catarina, au sud du Brésil. Les zones d'étude, reflets des écosystèmes présents sur l'île, sont toutes des réserves naturelles. Les résultats sont basés sur des prélèvements collectés sur le long terme (2003-2009), comparant les proportions de chaque reste sur plusieurs années et précisant la variabilité inter-annuelle et mensuelle. Pour toutes les zones, les poissons (71%) et les crustacés (25%) sont les principales proies, suivis par les mollusques (2%), les oiseaux (1%) et les mammifères (1%). Pour les principales catégories de proies, il n'y a pas de variabilité inter-annuelle ou mensuelle observée. Les résultats montrent que, sur l'île de Santa Catarina, la Loutre géante présente une composition alimentaire bien définie qui ne change pas de place en place, et n'a pas de variabilité inter-annuelle ou mensuelle.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Una Comparativa del Análisis de la Dieta de la Nutria Neotropical en la Isla de Santa Catarina, Brasil

Este trabajo representa una comparativa del análisis de la dieta de la nutria neotropical Lontra longicaudis mediante el análisis de excrementos (n=8841) en cuatro áreas diferentes localizadas en la isla de Santa Catarina, en el sur de Brásil. Las áreas de estudio, los principales ecosistemas encontrados en la isla, son todos reservas naturales. Los resultados están basados en datos a largo plazo (2003-2009) comparando las proporciones de productos alimenticios a través de los años, con una variabilidad interanual y mensual. Para todas las áreas de estudio, pescado (71%) y crustáceos (25%) son los principales tipos de comida, seguido de moluscos (2%), pájaros (1%) y mamíferos. En el caso de las principales categorías de comida, no se ha observado variación interanual o mensual de los productos alimenticios que componen la dieta de la nutria. Los resultados muestran que en la isla de Santa Catarina, la nutria neotropical presenta una dieta bien definida que no cambia de un lugar a otro y que no tiene variabilidad interanual o mensual.

Vuelva a la tapa

Resumo: Análise Comparativa da Dieta da Lontra Neotropical na Ilha de Santa Catarina, Brasil

Este trabalho representa uma análise comparativa da dieta de lontra neotropical (Lontra longicaudis) por análise de excremento (n= 8841) para quatro diferentes áreas, localizadas na Ilha de Santa Catarina, sul do Brasil. As áreas de estudo, os principais ecossistemas encontrados na Ilha, são todas reservas naturais. Os resultados são baseados em bancos de dados de longo termo (2003-2009) comparando proporções dos itens alimentares através dos anos, com variabilidade inter-anual e mensal. Para todas as áreas de estudo, peixes (71%) e crustáceos (25%) representam os principais itens alimentares, seguidos por moluscos (2%), aves (1%) e mamíferos (1%). No caso das principais categorias alimentares, não é observado variabilidade inter-anual ou mensal para os itens alimentares que compõem a dieta da lontra. Os resultados mostram que, na Ilha de Santa Catarina, a lontra neotropical apresenta uma dieta bem definida, que não muda de local para local, e não varia ao longo dos meses e entre os anos.

Voltar ao topo