IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

|

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group Volume 30 Issue 1 (January 2013) Citation: Ramírez-Bravo, O.E., Moreno Barrera, P.L. and Hernández-Santín , L. (2013). Public Participation as an Aid to Conserve Little Known Species: The Case of the Neotropical Otter Lontra Longicaudis (Olfers, 1818) in Central Mexico IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 30 (1): 39 - 43 Public Participation as an Aid to Conserve Little Known Species: The Case of the Neotropical Otter Lontra Longicaudis (Olfers, 1818) in Central Mexico O. Eric Ramírez-Bravo1,2,3, Paola Lizbeth Moreno Barrera4 and Lorna Hernández-Santín3

1Durrell Institute for Conservation Ecology, Marlowe Building, University of Kent, Canterbury, Kent, CT2 7NR, England, UK Email:

ermex02@yahoo.com

|

|

| (Received 7th February 2013, accepted 25th April 2013) |

| Abstract: Public participation is often disregarded during conservation projects despite the potential benefits as it can help to determine priority areas for conservation in highly fragmented landscapes or to increase knowledge of little known species. However, there is no information about its potential application in Central Mexico. We undertook a preliminary assessment based on 30 interviews preformed between December 2011 and May 2012 with hunters aimed to determine the presence, feeding habits, reproduction periods, and –threats of the neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis) in a fragmented landscape in the Sierra Madre Oriental. Twenty three of the interviewed hunters indicated that the species is rare and considered to be solitary however, they have observed cubs and pregnant females feeding mainly on fish and crustaceans were made. Pollution, shortage of prey, habitat disturbance, and hunting were the main threats on the species. We verified the presence responses of the neotropical otter through field work and the life history information was obtained by doing a literature review. We concluded that public participation can be confidently incorporated in conservation plans of the neotropical otter in the Sierra Madre Oriental. |

| Keywords: Puebla, Sierra Norte, communities, public monitoring |

| Française | Español |

INTRODUCTION

Despite the broad knowledge that local communities have on their environments and factors affecting species within their surroundings ( Danielsen et al., 2003 ), public participation in conservation projects has not been considered widely in conservation research ( Brook and McLachlan, 2008 ). It is now acknowledged that public participation can be useful to generate information of little known or secretive species. Public participation can be useful to determine species presence and corridor viability ( Zeller et al., 2011 ), to map important factors for conservation along the landscape ( Kingston et al., 2000 ), and to understand some ecological patterns of species such as preferred prey items ( Gallo-Reynoso, 1989 ).

The neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis) is a data deficient species, lacking information in most countries of its range ( Waldemarin and Alvarez, 2008 ; Gallo-Reynoso, 1989 ). In Mexico it is known to be a widely distributed species, however, most related studies focused on its feeding habits and distribution ( Casariego-Mandorell et al. 2006 ; Gallo-Reynoso et al. 2008 ; Monroy-Vilchis and Mundo, 2009) . Therefore, public participation could be useful in the conservation of the neotropical otters specially as they can live in areas which have a certain level of human activities ( Larivière, 1999 ), increasing the potential number of people that can provide information about the species.

Neotropical otters can be considered as a bio-indicator, selecting well-preserved areas ( Casariego-Madorell et al., 2006 ). The mountain range known as Sierra Madre Oriental is highly fragmented in some areas ( Evangelista et al., 2010 ), but has the potential to serve as a corridor for some species ( Ramirez-Bravo et al., 2010 ). However, current information on neotropical otters along Sierra Madre Oriental is punctual and refers mostly to its geographical distribution ( Gallo-Reynoso, 1989 ). Thus, available information can be used to test if public participation could supplement with -basic information for Lontra longicaudis management in Sierra Madre Oriental.

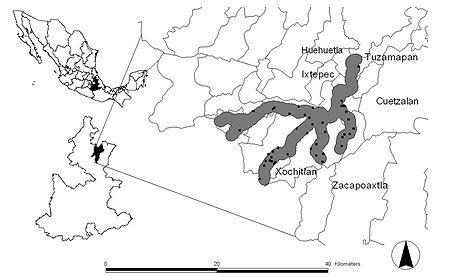

We undertook interviews with hunters and farmers from local communities within a portion of Sierra Madre Oriental in the Sierra Norte of Puebla to assess their knowledge on neotropical otters. The Sierra Norte, is located in the state of Puebla, in central Mexico; where only a few number of otters have been recorded ( Ramírez-Bravo, 2010 ). Sierra Norte has great altitudinal and climatic variation, resulting in high habitat diversity that ranges from tropical rainforest in the lowlands to temperate moist forest in high grounds (Ramírez-Pulido et al., 2005). We concentrated our efforts in a 141.21-km2 area, within the Cozoltepec River Canyon and its tributaries ( Fig. 1 ).

|

|

Figure 1.

Cozoltepec River Canyon in the State of Puebla, Central Mexico (click for larger version) |

We did a total of 30 interviews between December 2011 and May 2012. We selected fishermen and farmers who conducted agricultural activities close to tributaries of the rivers Cuichat and Zempoala in the municipalities of Tuzamapan de Galeana, Cuetzalan del Progreso, Huehuetla, Olintla, and Xochitlán de Vicente Suárez. We created a set of 24 questions aimed at determining the presence of the species, habitat description, threat impacts, and human activities in the area, and their influence on otters.

Most of the surveyed people are in the field all year round (23) and indicated that sightings are raren which could be due to the low population densities in the region as in other areas further south ( Casariego-Madorell et al., 2006 ). We recorded a total of 22 otter sightings, 13 in summer (June-August) and nine in spring (March-May) Interviewees reported otters being solitary, which behavior agrees with findings related to the ecology of the species in other parts of Mexico ( Gallo-Reynoso, 1989 ). Most sightings correspond to resting individuals (12), which is also the most reported activity in captive otters ( Green, 2000 ), followed by swimming (7) and feeding (7). Interviewees disclosed that otters feed mainly on “fish” or “crustaceans” (without giving further information on species); such behavior also agrees with reports related to otter feeding habits reports in other areas ( Casariego-Madorell et al., 2006 ; Gallo-Reynoso et al., 2008 ; Monroy-Vilchis and Mundo, 2009 ).

The interviewees were not able to comment on the otters' reproductive cycle; this is contrary to findings in areas where people depend on fishing ( Gallo-Reynoso, 1989 ). Furthermore, in general interviewees did not differentiate males and females. However, there were two reports of pregnant females, which were declared to be more robust. In addition, interviewees reported observations of young individuals, distinguished by differences in their size, color and calls, between March and July. This information differs from observations of young individuals made in Sierra Madre del Sur, where mating occurs during the dry season ( Gallo-Reynoso, 1989 ). Interviewees reported two cubs were accompanied by adults. In our study area, the main threats to neotropical otters are pollution, prey over-exploitation, habitat destruction, and hunting. All these threats were common in all surveyed communities, as well as in other areas in Mexico ( Gallo-Reynoso, 1989 ; Casariego-Madorell et al., 2006 ). We found that otters were taken by some locals to be raised as pets ( Ramírez-Pulido et al., 2005 ), but the main uses are as a source of protein (12) and for the skin trade (8). However, most of the interviewees (27) were not aware that otters are under protection and hunting them is prohibited.

The results obtained throughout this work were useful to prioritize areas significant for otter research as well as to propose a project to determine population densities and feeding habits in the region. Given the otters’ secretive and solitary nature in Sierra Norte, we found that interviewees had little knowledge of otters. Regardless, the results were enough to determine their presence and distribution. We considered that the use of public participation is useful and necessary, especially in cases of poorly studied species. Furthermore, this information can provide a baseline to select study areas for fieldwork, which can help to save resources. Thus, researchers should consider communities as a useful source of information in order to determine the best approaches for conservation projects.

REFERENCES

Brook, R.K., Mclachlan, S.M. (2008). Trends and prospects for local knowledge in ecological and conservation research and monitoring. Biodivers. Conserv.

17: 3501–3512

Casariego-Madorell, M.A. List, R., Ceballos, G. (2006). Aspectos básicos sobre la ecología de la nutria de rio (Lontra longicaudis annectens) para la costa de Oaxaca. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología. Instituto de Ecología UNAM 10: 71-74.

Danielsen, F., Mendoza, M.M., Alviola, P., Balete, D.S., Enghoff, M., Poulsen, M.K., Jensen, A.E. (2003). Biodiversity monitoring in developing countries: what are we trying to archive? Oryx 37: 407-409.

Evangelista Oliva, V., López Blanco, J., Caballero Nieto, J., Marrtínez Alfaro, M.Á. (2010). Patrones espaciales de cambio de cobertura y uso del suelo en el área cafetalera de la Sierra Norte de Puebla. Investigaciónes Geográficas, Boletín del Instituto de Geografía, UNAM

72: 23–38.

Gallo-Reynoso, J.P. (1989). Distribución y estado de conservación de la nutria o perro de agua (Lutra logicaudis annectens Major; 1897) en la Sierra Madre del Sur, México. Tesis de Maestría no publicada. Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM, División de Estudios de Posgrados. México. 236 pp.

Gallo-Reynoso, J.P., Nayeli, N., Óscar, R. (2008). Depredación de aves acuáticas por la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens ), en el río Yaqui , Sonora , México. Revista Mexicana De Biodiversidad 79:275–279.

Green, R. (2000). Sexual Difference in the behavior of young otters (Lutra lutra). IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull.

17: 20–30.

Kingston, R., Carver, S., Evans, A., Turton, I. (2000). Web-based public participation geographical information systems: an aid to local environmental decision making. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 24, 109-125.

Larivière, S. (1999).

Lontra longicauidis. Mammalian Species

609: 1-5.

Monroy-Vilchis, O., Mundo, V. (2009). Nicho trófico de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis) en un ambiente modifi cado , Temascaltepec , México. Revista Mexicana De Biodiversidad

80: 801–806.

Ramírez-Bravo, O.E. (2010). Reporte del Jaguar en Puebla: Presencia, distribución, relación con el hombre y conservación,Reporte para el segundo año, 2009-2010, 68 pp.

Ramírez Pulido, J., González-Ruiz, N., Genoways H.H. (2005). Los carnívoros del estado Puebla Mexico: Distribución, taxonomía y conservación. Mastozoología Neotropical

12: 37-52.

Waldemarin, H.F., Alvarez, R. (2008).

Lontra longicaudis. In: IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. <

www.iucnredlist.org

>. Downloaded on 26 December 2012.

Zeller, K., Nijhawan, S., Salom-Pérez, R., Potosme, S. H., Hines, J. E. (2011). Integrating occupancy modeling and interview data for corridor identification: A case study for jaguars in Nicaragua. Biol. Conserv.

144: 892–901

Résumé : Participation du Public à la Conservation d'Espèces Peu Connues: Cas de la Loutre à Longue Queue Lontra Longicaudis (Olfers, 1818) dans le Centre du Mexique

La participation du public est souvent négligée dans les projets de conservation en dépit des avantages potentiels que cela peut apporter notamment dans la détermination des zones prioritaires de conservation dans des paysages très fragmentés mais aussi à accroître les connaissances des espèces peu connues. Quoi qu'il en soit, il n'existe aucune information sur son application potentielle dans le centre du Mexique. Nous avons entrepris une évaluation préliminaire basée sur 30 interviews entre Décembre 2011 et mai 2012 auprès de chasseurs afin de déterminer la présence de la Loutre à longue queue (Lontra longicaudis), ses habitudes alimentaires, les périodes de reproduction et les menaces qui pèsent sur elle dans un habitat fragmenté de la Sierra Madre Oriental. Vingt-trois des chasseurs interrogés ont indiqué que l'espèce est rare et solitaire et qu'ils ont observé des loutrons et des femelles gestantes se nourrissant principalement de poissons et de crustacés. La pollution, la pénurie de proies, les perturbations de l'habitat et la chasse sont les principales menaces pesant sur l'espèce. Nous avons vérifié les témoignages de présence par une enquête de terrain et les informations relatives au cycle de vie ont été validées via la littérature. Nous avons finalement conclu que la participation du public peut être intégrée en toute confiance dans les plans de conservation de la Loutre à longue queue dans la Sierra Madre Oriental.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: La Participación Pública como una Ayuda Para Conservar una Especie Poco Conocida: El Caso de la Nutria Neotropical Lontra Longicaudis (Olfers, 1818) en el Centro de Mexico

En general la participación pública no es tomada en cuenta en proyectos de conservación a pesar de sus beneficios potenciales para identificar áreas prioritarias para la conservación en paisajes fragmentados, o para incrementar el conocimiento de especies poco conocidas. A pesar de esto, no existe información sobre el potencial de aplicación de este método en el Centro de México. Por lo anterior, llevamos a cabo un estudio preliminar basado en 30 encuestas a cazadores para determinar la presencia, hábitos alimenticios, época de reproducción y cacería de la nutria de río (Lontra longicaudis) en un paisaje fragmentado en la Sierra Madre Oriental. Veintitrés personas respondieron que la especie es rara y se considera solitaria pero, han llegado a observar cachorros y hembras cargadas además; los entrevistados identifican a peces y crustáceos como los componentes principales de la dieta. La amenaza principal para la especie se considera la contaminación, sobre explotación de las presas, disturbios en el hábitat y cacería. Se verificó la presencia de la especie mediante trabajo de campo y el resto de la información se verificó a través de una revisión bibliográfica. De esta manera, se concluyó que la participación pública puede ser incorporada confiablemente al elaborar planes de conservación en la Sierra Madre Oriental.

Vuelva a la tapa