|

Last Update:

Thursday November 22, 2018

|

| [Home] |

INTRODUCTION During an otter survey on the west coast of Turkey and its hinterland freshwater rivers in summer 1994, A. Kranz, N. Ziegler and M. Weiss collected about 100 otter spraints ( Fig. 1 ). These spraints were analyzed to determine the impact of otters on local fish, domestic animals and game species. The results of this study should help to resolve the conflict between otter conservationists and local otter poachers ( Kranz, 1994 ). This is one of the first studies on otters in Turkey, where little is known about the status of the species ( Mason and Macdonald 1986 ).

METHODS The 100 dryed otter spraints were soaked for 48 hours in detergent water and washed through a 0,8 mm strainer. The remaining bones, scales and feathers were analyzed with a binocular (6x-50x) and determined with support of reference collections and drawings taken from literature ( Brohm, in prep .; Conroy et al., 1993 ; Engelmann, 1986 ). Size of the most important fish species in the otter diet was estimated by measuring the vertebrae lengths ( Conroy et al., 1993 ; Wise, 1980 ). The results were shown as relative frequencies of occurrence, i. e. the frequency of a prey category is presented as a percentage of all prey occurrences ( Erlinge, 1967 ; Conroy et al., 1993 ; Hansen and Jacobsen, 1992 ). The spraints of four different sample areas were evaluated separately. The spraints of the other study sites formed together the fifth sample. RESULTS

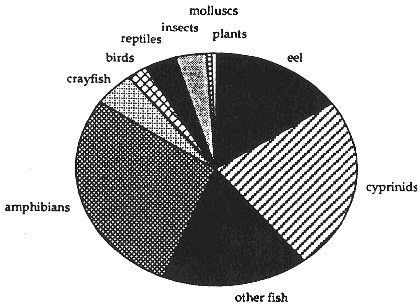

In 100 analysed spraints 167 feeding remains belonging to 16 prey categories were identified (see Tab. 1 ). Fish (55.7%) and amphibians (28.7%) were the most important prey categories ( Fig. 2 ). At the first study site (Hisaronu, n = 15) most of the diet was Anguilla anguilla (37%), Leuciscus sp. (29.6%) and amphibians (22.3%). Apart from the low occurrences of trout, perch and cyprinids were found in the spraints. This site provided the highest portion of fish of the whole study area (77.7%). On the River Kizil De amphibians were the dominant prey (51,1%). Other prey included birds (7.4%), insects (7.4%) and molluscs (3.7%). The fish species with the highest occurrence were again eel (11.1%) and chub (7.4%). The total portion of fish was 29.6%, the lowest in the whole study. On the River Gelibolu the total fish portion was 50% (mostly small juvenile chubs 41%). The rest of the prey were amphibians (18.2%), crayfish (13.6%), reptiles (9.1%) and insects (4.5%). Gelibolu was the only study site with no eel. In one spraint large undigested plants were found. Akcarpinar was the only study site (close to the sea) where the presence of sea-fish (47.5%; 9.5% of them were Mugil sp. and 4.7% Roccus labrax) was recorded. The other 33.3% were other unidentified sea-fish (probably one or two different species). Freshwater fish such as eel (9.5%), perch (4.7%) and trout (2.4%) were found in this site. Apart from fish, amphibians (19%), birds (2.4%), crayfish (9.5%) and insects were found in the spraints. The total number of prey categories (10) was the highest of all five sites. In the remaining spraint samples amphibians (32.7%), reptiles (8.2%), birds (2%), crayfish (2%) and insects (mostly large waterbeetles, 4.1%) were found. Eel (18.4%), chub (8.2%), trout (8.2%) and unidentified cyprinids (14.2%) formed a total fish portion of 51%.

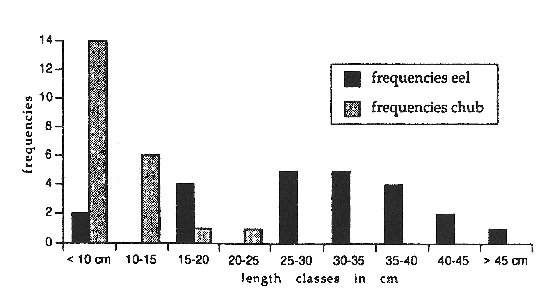

In total the lengths of 55 fishes eaten by otters were calculated ( Fig. 3 ). Eel had a mean length of 29,3 cm (range 9 to 45 cm). Most chub were less than 10 cm (the biggest being about 25 cm long).

DISCUSSION Allthough the numbers of spraints were relatively low the results of this study are similar to those of other studies in the Mediteranean area ( Adrian and Delibes, 1987 ; Arcá and Prigioni, 1987 ; Fasano, 1991 ; Prigioni et al., 1986 ; Macdonald and Mason, 1982 ). The portion of fish (55.7%) is much lower than that found in study areas in Central and Northern Europe ( Erlinge, 1967 ; Knollseisen, 1995 ; Kruuk and Moorhouse, 1990 ). In Turkey the occurrence of fish in the diet of otters was lower than in Italy ( Arcá and Prigioni, 1987 ; Fasano, 1991 ) but as high as in Albania ( Prigioni et al., 1986 ) and in Greece ( Macdonald and Mason, 1982 ). Amphibians (up to 51.9%), crustaceans (up to 13.6%) and reptiles (up to 9.1%) were other important prey categories. Eel was the most frequently eaten fish species by the otter. This is probably due to the way of life of the eel which makes it an easy prey for otters. Like in Southern Italy ( Fasano, 1991 ) most eel found in otter spraints were about 30 cm long. The large number of juvenile cyprinids (mostly Leuciscus sp.) in the diet has also been observed in Central Europe ( Knollseisen, 1995 ; Roche and Hofmann, pers. comm.). At the Akcarpinar otters fed on marine fish but it is not clear wether the otter caught them in the sea (in 1994 otter occurrences on the coast of Turkey were found; Kranz, pers. comm.) or in the freshwater (both species identified in the spraints can be recorded regularly even in the freshwater; Muus and Dahlström 1990 ). Another explanation is that otters fed on marine fish thrown away by local fishermen at the study site (spraints were found in a little harbour where local fishermen cleaned their nets after turning from the sea; Ziegler, pers. commun.). These results are one of the firsts to indicate otters feeding in the Mediteranean Sea (Table 2). Otters can be found frequently in marine environments in Northern Europe (e. g. Kruuk and Moorhouse, 1990 ) but only rarely in Southern Europe (e. g. singular observations in Italy; Fasano, pers. comm.; Greece, Gutleb, pers. comm). The analysis of the 100 spraints from freshwater habitats in Turkey did not show any evidence for condemning the otter as a pest for local fish or domestic galinaceous birds. The single bird occurrences found in the otter spraints were small juvenile song-bird. From the large number of small cyprinids in the otter diet it is not allowed to infer directly on a impact of otters on juvenile fish stock; other influences on small fish like sudden floods or drying of ditches or river stretches are maybe much more catastrophic for juvenile fish than the feeding of otters. Only the connection of otter predation and abiotic influences can become problematic for fish populations (e.g. otters entering in small almost dry ponds or ditches). For further information on the impact of otters upon their prey or upon domestic animals a more detailed study would be necessary.

Acknowledgements - I am very grateful to N. Ziegler and M. Weiss from AGA for the supply with the spraints (collected partly by A. Kranz) and to AGA (Aktionsgemeinschaft Artenschutz e. V., Germany) for the financial support. REFERENCES

Adrian, M.I., Delibes, M. (1987). Food habits of the otter (Lutra lutra) in two habitats of the Donana National Park, SW Spain. J. Zool. Lond., 212: 399-406 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Copyright © 2006 - 2050 IUCN/SSC OSG] | [Home] | [Contact Us] |