|

Last Update:

Thursday November 22, 2018

|

| [Home] |

|

Volume 19 Issue 2 Pages 62 - 110 (October 2002) Citation: van Damme, P., Wallace, R., Swaenepoel, K., Painter, L., Ten, S., Taber, A., Gonzalez Jimenes, R. Saravia, I., Fraser, A. and Vargas, J. (2002) Distribution and Population Status of the Giant Otter Pteronura brasiliensis in Bolivia. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 19(2): 87- 96 Distribution and Population Status of the Giant Otter Pteronura brasiliensis in Bolivia Paul van Damme1, Rob Wallace2, Karen Swaenepoel3, Lillian Painter2, Silvia Ten4, Andrew Taber5, Rocio Gonzalez Jimenes6, Isabel Saravia1, Anna Fraser7 and Julieta Vargas8 1 Programa de

Conservación y Manejo de Recursos Hidrobiológicos (COMARH), Centro de

Limnologia y Recursos Acuáticos, Universidad Mayor de San Simón, Cochabamba,

Bolivia. e-mail: Paul.vandamme@bo.net (received 15th December 2002, accepted 12th January 2003)

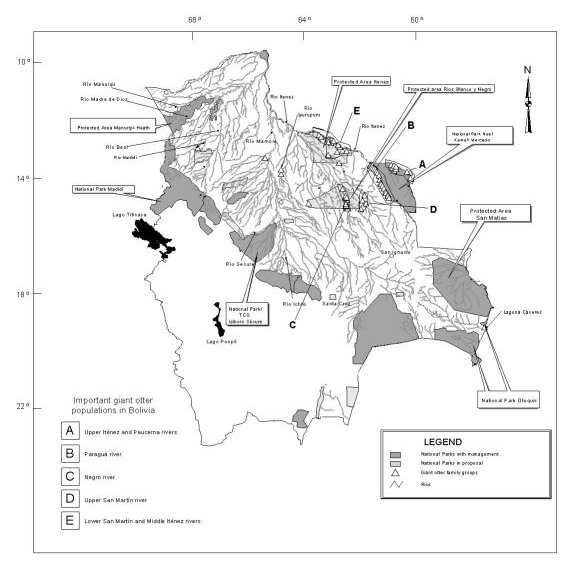

INTRODUCTION The giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) used to be a common sight in the Bolivian river floodplains. As in all neighbouring countries, the species was decimated to the border of extinction by poaching between the 1940s and 70s. Between 1975 and 1995, the species was only known from very isolated locations in the Mamoré, Iténez and Madre de Díos basins (DUNSTONE and STRACHAN, 1988; CAMERON et al., 1989; BARRA et al. 1992). On a continental scale, Bolivia represented one of the black spots on the distribution map of the giant otter (EISENBERG and REDFORD, 1999). This pessimistic view changed with the discovery of relatively healthy populations in the Iténez-Guaporé river basin by PAINTER et al. (1994), GONZÁLES JIMÉNEZ (1997), FRASER et al. (1993), van DAMME et al. (2002) and PALMER (pers. comm.). These authors reported a minimum total population of 350 individuals, organized into more than 40 family groups. The present report summarizes the distribution and population status of this species. We also discuss the protection status of the respective giant otter populations and the possibilities of interchange between neighbouring populations. This report is a brief summary of a recently published review (van DAMME et al., 2002). METHODS The present report is based on field observations from the period 1993-2002. Some of the observations have been published in scientific articles (TEN et al., 2001), but most were only available in relatively inaccessible reports (FRASER et al., 1993), Management Plans of National Parks (FAN-WCS, 1994; PAINTER et al., 1994), RAP expedition reports (EMMONS, 1998) and student theses (GONZÁLES JIMÉNEZ, 1997; SARAVIA, unpubl.). None of the previously mentioned authors used a standardized methodology, though there are some constant patterns in their approach. For example, most observed otters from a boat, which in most cases was equipped with an outboard motor. Some observations were made in the framework of other studies on neotropical mammals. FRASER et al. (1993) conducted a study on giant otters in the River Iténez. GONZÁLES JIMENEZ (1997) and van DAMME et al. (2002) focused their attention on the River Paraguá, on the western border of the Noel Kempff Mercado National Park. PAINTER et al. (1994) conducted field surveys in the Blanco, Negro, Negro de Caimanes and San Martin rivers, whereas TEN et al. (2001) focused on more downstream segments of the latter river and other rivers in the Iténez National Park. In addition, isolated observations were made by REBOLLEDO and QUIROGA (unpublished data) in the Bolivian Pantanal, VARGAS (unpublished data) in the Etanahua river (Madidi River basin), TORRES (unpublished data) in the Ipurupuru River (Iténez-Guaporé basin), and WALLACE, PAINTER, TABER and RUMIZ (unpublished data) in the Iténez-Guaporé, Negro and San Martin rivers (for a summary see van DAMME et al. 2002). RESULTS Distribution and population status In Bolivia the largest populations of giant otter occur in the Iténez-Guaporé river basin. In this basin, four important populations were reported:

In the Mamoré river basin, very few giant otters have been recently observed. In the upper Mamoré basin, some historical records exist. The last known group in the Ichilo river basin (in an oxbow lake of the Sajta river) was extinguished a few years ago. The last giant otters in this river basin may occur in the Isiboro-Sécure National Park, where indigenous people have observed them. Finally, in the most western parts of the Amazon basin, in the Madre de Díos and Beni river basins, individual otters or isolated family groups were recently recorded in the Heath, Madidi, Etanahua, Tuichi, Hondo, Quiquibey, Emero and Tequeje rivers (WALLACE et al., unpublished data; MONTAMBAULT, 2002; VARGAS, unpublished data). CARBAJAL (pers.comm.) recently observed a group of 8 giant otters in the Manuripi-Heath National Park (not indicated in Fig. 1). A systematic survey of these rivers has not been carried out so far. In the basin of the Paraguay river, the giant otter has not been studied very well, though it may be expected to occur given its proximity to the Brazilian pantanal, where a relatively large population of giant otters occurs (SCHWEIZER, 1992). Recently, a family group was observed in the Cáceres lake, within the Otuquis National Park (REBOLLEDO Y QUIROGA, pers. comm.). Habitat selection

Among the sectors that can be distinguished in these hydro-regions, the giant otter was most often reported in the alluvial lowlands of the Precambrian Shield (88.5% of all individuals), overlapping with the floodplain of the Iténez-river and some of its tributaries (Paraguá and San Martin rivers). Fewer individuals were recorded in the Fluvial alluvial lowlands of the white-water floodplains of the Mamoré and Madre de Díos rivers, whereas in other sectors only anecdotal and historical reports were available. Overall, more than 85% of the observations so far were made in small rivers, most of them draining the Precambrian Shield. So far, very few giant otters have been reported in white-water oxbow lakes, though they are expected to occur. Protection status of the giant otter

1 The giant otters observed in the TCO Tacana were not included DISCUSSION The giant otter is a rare species in Bolivia and is found only in National Parks and in remote areas. According to preliminary estimates, the minimum population size is 350 individuals. However, the effective population size is much smaller, considering that each family group consists of only two adults. The population status is particularly alarming in the white-water floodplains of the Amazon (Mamoré, Beni and Madre de Díos river basins), though low estimates may partly reflect low research effort in this area. In the Iténez-Guaporé river basin, however, relatively healthy populations can be found in the black-water floodplains of the rivers San Martin, Paraguá, Paucerna, Iténez and Negro. One of the central issues in conservation science is the degree of isolation of animal populations. EISENBERG (1989) and EISENBERG and REDFORD (1999) indicated that the actual giant otter populations have a patchy distribution in the Amazon, with little possibilities of gene interchange. Connection of Peruvian and Bolivian populations in Peru is highly probable considering the conservation status of the border area (Bahuaja-Sonene and Madidi National Parks in Peru and Bolivia, respectively). The nearby populations in Brazil (> 500 ind.) can be found in the Bolivian Pantanal (SCHWEIZER, 1992; CARTER and ROSAS, 1997), but connection between the Amazon and Pantanal populations is less probable given the fact that the Pantanal belongs to the La Plata river basin and that interchange can only be realized over land, which is heavily affected by deforestation. In the Brazilian states of Rondonia and Mato Grosso, some conservation units neighbouring the Noel Kempff Mercado and Iténez National Parks might also harbour giant otters, though so far there are no otter reports from these areas. Within Bolivia, connection between the upper Iténez and middle Iténez populations is highly probable (subpopulations A and E in Fig. 1). The major human impact on this river is commercial navigation and commercial fisheries, but it is thought that these activities do not disrupt the function of the River Iténez as a corridor for giant otters. The population in the upper San Martin and Negro rivers (subpopulations C and D in Fig. 1) may be relatively more isolated as they are separated from the lower river populations by a colonized area, characterized by increased deforestation and habitat destruction. Interconnections of the populations of the Blanco y Negro protected area (subpopulations C and D in Fig. 1) and the Noel Kempff Mercado National Park (subpopulation B) might be realized by individuals that cross terra firma forest. According to some authors (WALLACE, pers. obs.) giant otters may cross high forest stretches, but the relative importance of this terrestrial route is not known. In Surinam and Guyana, the giant otter seems to prefer slow-moving rivers with transparent water (DUPLAIX, 1980; LAIDLER, 1984). This also seems to be the case in Bolivia, where giant otters are predominantly found in the so-called black- or clear-water rivers that drain the Precambrian Shield. These rivers are characterized by a high water transparency, abundance of submerged and emergent macrophytes (KILLEEN and SCHULENBERG, 1998) and the occurrence of steep riverbanks. The giant otters prefer the downstream segments of these rivers, upstream parts probably not providing enough food to sustain viable populations. In the past, giant otters probably inhabited white-water oxbow lakes, an otter habitat similar to the one described for this species in the Manú and Bahuaja-Sonene National Parks in Peru (SCHENK and STAIB, 1998; GROENENDIJK et al., 2001), and in lakes of tectonic origin. This is indicated by their relict presence in these habitats in the white water floodplains of the rivers Mamoré, Beni and Madre de Díos. There are also indications that they occurred historically in the clear water tributaries of these white water rivers. The white water river channels themselves were possibly used as corridors for colonization of new river stretches or lakes. There are strong indications that general habitat characteristics determined the original distribution patterns of giant otters in Bolivia. Other factors, such as food availability, and carrying capacity may become important in smaller river basins where the carrying capacity for giant otters is reached, such as on the rivers Paraguá, San Pedro and San Martin in the Iténez river basin. In some of these rivers, competition for fish with fishermen may already occur (van DAMME et al., in prep.). The spatial distribution and the abundance of the fish resource may also determine giant otter group size. For example, in the lower San Martin river, large groups of up to 20 individuals (possibly 2 or 3 family groups that temporally feed together) are sometimes formed around fish-rich river stretches that dry up in summer (TEN, pers. obs.). Nevertheless, current distribution pattern of giant otters in Bolivia may reflect the ease of human access to areas where giant otters originally occurred. The giant otter is extremely susceptible to hunting pressure. Its large size, diurnal activity and social behaviour make it an easy prey for fishermen who assert that giant otters compete with them for fish, and to occasional hunters in search of a trophy (OJASTI, 1996; GROENENDIJK et al., 2001). The negative correlation between human population density and otter occurrence suggests that human presence represents a major threat to the species and is probably related to the booming skin trade of the last century, In Bolivia, occasional kills, habitat loss and disturbance caused by river traffic seem to be important causes of current population stagnation or decrease (van DAMME et al., 2002). Mercury contamination (MAURICE-BOURGOIN et al., 1999) and demographic isolation of populations may represent additional threats that will need to be seriously considered in the future. This situation makes the development of national research and conservation strategies for the species a pressing priority, particularly given the flagship nature of the species, the globally threatened situation for giant otters, the probable ecological importance of the species, and the potential economic importance in terms of ecotourism opportunities. REFERENCESBarra, C., Maldonado, M., Goitia, E., Acosta, F.,

Cadima, M. Arrázola, S. 1992. Prospección de los recursos hidrobiológicos

en el sistema del río Isarsama, Cochabamba. Unpublished report. 47 p. Résumé : Répartition et Statut des Populations de

Loutres Géantes Pteronura brasiliensis en Bolivie Resumen: Distribución y Estado Poblacional de la

Nutria Gigante Pteronura brasiliensis en Bolivia |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Copyright © 2006 - 2050 IUCN/SSC OSG] | [Home] | [Contact Us] |