IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Volume 35 Issue 4 (December 2018)

Citation: Morales-Betancourt, D and Medina Barrios, OD (2018). Notes on Neotropical Otter (Lontra longicaudis) Hunting, a Possible Underestimated Threat in Colombia . IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 35 (4): 198 - 202

Notes on Neotropical Otter (Lontra longicaudis) Hunting, a Possible Underestimated Threat in Colombia

Diana Morales-Betancourt 1 and Oscar Daniel Medina Barrios2

1 Universidad Externado de Colombia, Cl. 12 #1-17 Este, Bogotá, Colombia

Email: dianamoralesb@yahoo.com

2 Animal Care Coordinator, Fundación Botánica y Zoológica de Barranquilla, Cl. 77 #68-40 Barranquilla, Colombia

Email: o.medina@zoobaq.org

Received 12th March 2018, accepted 15th June 2018

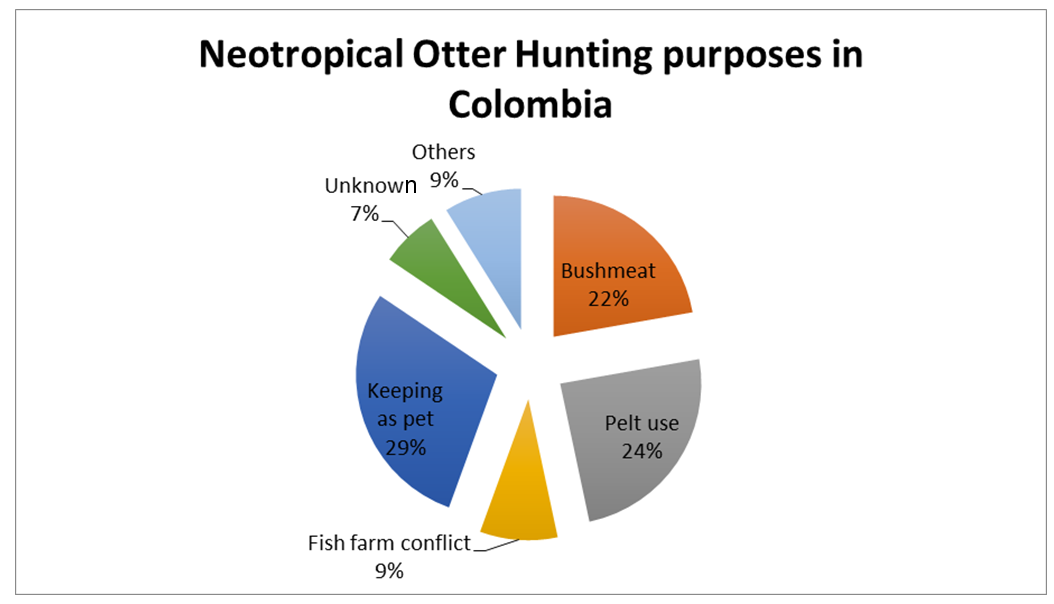

Abstract: Since Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis) hunting was legally banned in 1973 in Colombia, hunting is no longer considered to be a high priority conservation concern in the Country. The species is still classified as Vulnerable in the country, but the National Mammals Red List and the National action plan for aquatic mammals’ conservation in Colombia do not consider any use of the species besides keeping it as pet (an illegal activity in Colombia). A preliminary survey to identify current hunting activity was conducted professionals at biological research institutions, environmental NGO’s, university professors and regional environmental authorities, to identify current hunting among the five ecoregions in Colombia. The overall results among ecoregions show the main reasons for hunting Neotropical otters are: keeping as pet (29%), pelt use (24%) and bushmeat (22%). The results create a basis for gathering more information on the hunting of Neotropical otters in Colombia.

Keywords: Bushmeat, Colombia, hunting, Lontra longicaudis, Neotropical otter, wildlife use.

In Colombia, wildlife hunting is only permitted for subsistence (Congreso de Colombia, 1989). Althoughthis is legally allowed only to obtain wildlife meat for personal consumption, the illegal sale of bushmeat is a persistent conservation concern for certain species, including, for example, the capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) (van Vliet et al., 2016).

In 1973 the killing of mustelids, felines and large mammal species with fur of economic value was banned in Colombia due to overexploitation. At that time, the main threat to the Neotropical otter was hunting for the international pelt trade but, beginning some time in the early 1990s, the species was killed to reduce its depredation of shrimp and fish-culture facilities. This killing coincided with aquatic and riparian habitat degradation and pollution, which combined to contribute to the isolation and reduction of Neotropical otter populations, including extirpations in some watersheds (Trujillo and Arcila, 2006). In the National Red List for mammals, two hunting motivations are listed for Neotropical otter hunting: to sell caught pups as pets; and to make “carrieles” (a traditional satchel) and drums with the pelt, but the latter only occurred in a few communities, some decades ago (Trujillo and Arcila, 2006).

The National action plan for the conservation of aquatic mammals in Colombia (Trujillo, et al., 2014) bases its conservation strategy on a problem tree analysis, which only includes the threats identified in the The National Red List published in 2006. Unfortunately, during the workshops conducted in 2015 for the National Conservation Plan for Otters (Lontra longicaudis and Pteronura brasiliensis) in Colombia (Ministerio de Ambiente, y Desarrollo Sostenible & Fundación Omacha, 2016), the same threats for the species were evaluated, despite the participation of many regional environmental authorities and NGOs. In consequence, the strategies for this species do not correspond to the likely current situation.

The results in La Guajira department[1] research provided motivation to conduct an initial assessment to determine if hunting is a conservation concern for Neotropical otters in Colombia. To accomplish this initial assessment, a questionnaire was designed and sent it to different research institutions, NGOs, university professors and regional environmental authorities, with the aim of gaining insight on the potential threat hunting may pose for the conservation of Neotropical otters.

[[1] Department is the first-level country subdivision, similar to state for other countries]

An open question survey to gather otter hunting information (hunting activity presence, how recently, purpose or motivation, and related information about hunting), were sent to 148 conservation professionals (independent researchers, researchers at universities and national research institutes and professionals at regional environmental authorities) by email. In total, 37 responses were received; within these, 49 uses and purposes for hunting Neotropical otters were reported.

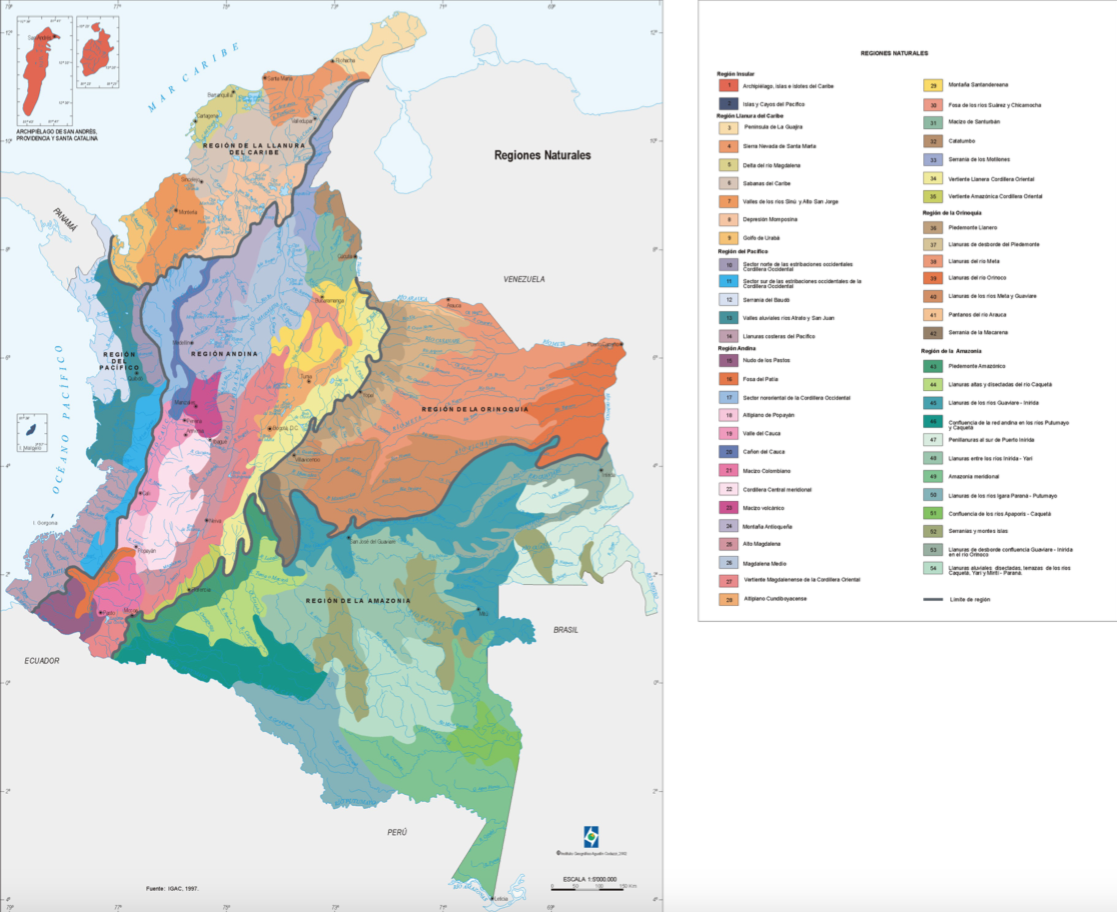

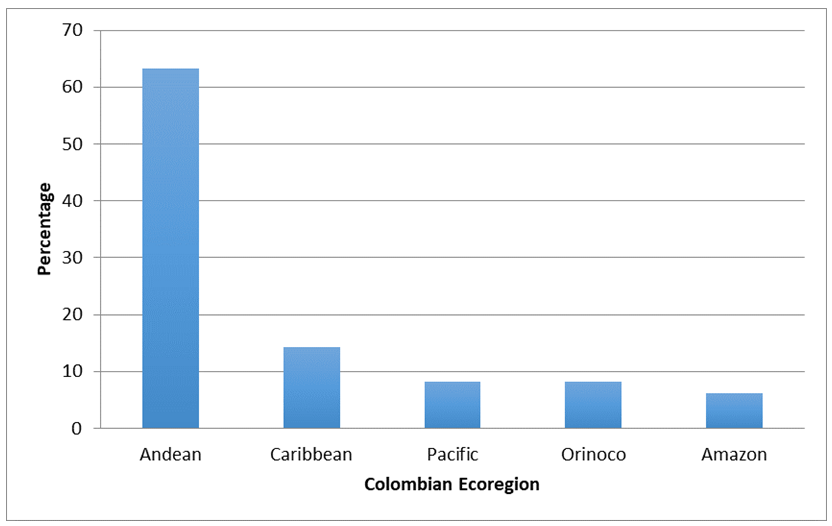

The results were organized according to the five biogeographic regions in Colombia: Andean, Pacific, Caribbean, Orinoco and Amazon (Figure 1). Responses were categorized according to the hunting reason or use: good luck, medicinal, “ombligar” (cutting the umbilicus of a newly born child), bushmeat, pet use, conflict with fisheries, and other unknown reasons.

(click for larger version)

The majority of experts providing responses represented the Andean ecoregion (63.3%; Figure 1). Hunting Neotropical otters for pelts remains problem and was the main use reported in that region (32.2% of responses), followed by the capture of otters for use as pets (29% responses). This pelt trade is well known to the regional authority Corantioquia, which developed an awareness campaigns to avoid otter pelt usage to make “carrieles.” (satchels carried by men over the shoulder). The information from this region is concentrated in the east area of Antioquia department and the area of Magdalena Medio (the Middle Magdalena river valley area) in Santander department. There are also indications of hunting in the Huila department, but the evidence is poorly verified and needs additional investigation.

The Caribbean ecoregion responses represented 14.3% of the total data gathered. Currently, hunting of Neotropical otters is reportedly taking place in the area, primarily for pets (cubs are caught for this purpose) and/or killing for bush meat, although other, lesser reasons for hunting were reported. Hunting otters for pets and bushmeat were both indicated by 29% of respondents from the region. Use as pets was reported in the Córdoba department and bushmeat use in the La Guajira department. For bushmeat use, women oversee post-hunting procedures to process the carcass (e.g., gutting, skinning, quartering, and hauling meat), and procedures important to make the meat palatable, especially avoiding contamination from anal scent glands. Following this, meat is salt-cured, and after a couple of days it can be prepared as food: the meat is first cut or shredded and then cooked in liquid for a stew or soup or simply pan-fried. An alarming fact is that the woman stated that although men do not go hunting specifically for otters, they will always hunt them if otters are available.

(click for larger version)

Prior to this investigation, consumption of otters had never been reported in Colombia. A new use of otters was also described among survey responses, where otters were reportedly to once have been hunted to extract their eyes, which were then used as the eyes of religious figures in Catholic statues. Members of local communities recall that hunters were well paid for the eyes (no specific amounts were provided), but this use is no longer a practice.

The Pacific ecoregion represented 8.2% of respondents. Here, it was reported that some Afro-Colombian communities use parts of the Neotropical otter as an element of their traditional beliefs, including medicinal purposes and for good luck (i.e. there is a ritual that include the use of otter eyes to increase a person’s good luck). There is also a traditional practice from some indigenous communities in the region called “ombligar,” which is associated with newborn children. Specifically, a midwife uses the toenail of a Neotropical otter to severe the umbilical cord from a newborn infant; afterwards the umbilical cord is buried and a tree is planted above to create deeply-rooted feelings into the newborn to his or her native land. There is no use as bushmeat in this ecoregion because the local communities think that the meat tastes “very marshy”.

In the Orinoco and Amazon ecoregions (8.2% and 6.1% of responses, respectively), the giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) is also present, which make it difficult to determine whether information derived by local people pertains to this species, the Neotropical otter, or both. In the Orinoco ecoregion, bushmeat, use as pets, and killing to reduce conflicts with fisheries were reported as purposes for hunting otters. In the Amazon there was one report of otters being used for bushmeat (in the Andean foothills), and two reports of otters being kept by local people as pets.

This preliminary research indicates that hunting of Neotropical otter occurs in all the Colombian ecoregions, and for various purposes (Figure 3). However, there was considerable variation in the amount of information collected among regions and additional information is needed to better elucidate the purpose, types, and potential impacts of hunting on Neotropical otter. The consolidated results among ecoregions shows that main hunting reasons for hunting Neotropical otters are: keeping as pet (29%), pelt use (24%) and bushmeat (with 22%). In relation to pet commercialization and ownership, data show that the number of confiscated or voluntarily surrendered animals oscillates between one to five individuals at a time; this indicates that each report of commercialization and ownership involves multiple individuals, which may lead to this threat having a more severe impact on this species than the other threats.

Reasons for Neotropical Otter hunting in Colombia, according to results of a survey conducted during 2016 (February – November).

(click for larger version)

<

In conclusion, we determined that Neotropical otters are currently hunted in all five ecoregions and at least 13 departments in Colombia. This project provides an important basis for conducting further research on the potential impacts of hunting on Neotropical otter populations. Future research should include ethnozoological and anthropological investigations related to hunting Neotropical otters, including the collection of more detailed data from specific areas of potential conservation concern, but also to continue collecting generalized information from areas poorly represented in our survey to fill geographical gaps of information. Even though the Neotropical otter is not currently prioritized as a species of high conservation concern in Colombia, synergistic effects can cause extirpation in some areas, especially where populations are isolated. We specially recommend that data on the hunting of Neotropical otters be gathered in Nariño, Tolima, Caquetá, Cundinamarca, Casanare, Boyacá, Chocó, Arauca, Norte de Santander, Sucre, Bolívar, Atlántico Magdalena and Cesar departments.

Acknowledgements: To all the organizations and people that collaborate with information in order to make possible this scientific note, specially to regional environmental authorities: Corantioquia, CVC, Corpourabá, CRQ, CAM, CAR, and other institutions such as: Fundación Bosques y Humedales, Biotica Consultores LTDA, Universidad Católica de Oriente and to researcher Carolina Zapata Escobar.

REFERENCES

Congreso de Colombia (Diciembre 27 de 1989). Estatuto nacional de protección de los animales, Ley 84 de 1989. Diario oficial No. 39120. Bogotá. D.E. [In Spanish]

Chardonnet, P., Fritz, H., Zorizi, N., Feron, E. (1995). Current importance of traditional hunting and major contrasts in wild meat consumption in Sub-Saharan Africa. En: Bissonette, J. A., Drausman, P. R. (Eds.), Integrating people and wildlife for a Sustainable Future, pp. 304-307. The Wildlife Society, Bethesda, USA.

Elliott, J., Grahn, R., Sriskanthan, G., Arnold, C. (2002). Wildlife and Poverty Study. Livestock and Wildlife Advisory Group, Department for International Development, London, UK.

Medina Barrios, D., Sierra A. M., Trujillo, F. (2015). Características de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis). In: Corpoguajira and Fundación Omacha, Plan de manejo para la conservación de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis) en el departamento de La Guajira, pp.11-18. Bogotá: Corpoguajira y Fundación Omacha. [In Spanish]

Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible, Fundación Omacha. (2016). Plan de manejo para la conservación de las nutrias (Lontra longicaudis y Pteronura brasiliensis) en Colombia. Bogotá: Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible. [In Spanish]

Morales-Betancourt, D., Páez-Vásquez, M., Rodríguez-Ovalle, G., Sierra, A. M. (2015). La comunidad local y su percepción sobre las nutrias. In: Corpoguajira and Fundación Omacha, Plan de manejo para la conservación de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis) en el departamento de La Guajira, pp. 27-34. Bogotá: Corpoguajira y Fundación Omacha. [In Spanish]

Peres, C. A. (2000). Effects of subsistence hunting on vertebrate community structure in Amazonian forest. Conservation Biology 14: 240-253.

Trujillo, F., Arcila, D. (2006). Nutria neotropical Lontra longicaudis. In: Rodríguez-Mahecha, J. V., Alberico, M., Trujillo, F., Jorgenson J. (Editores.). Libro Rojo de los Mamíferos de Colombia. Serie Libros Rojos de Especies Amenazadas de Colombia, pp 249-254. Bogotá: Conservación Internacional Colombia y Ministerio de Ambiente Vivienda y Desarrollo Territorial. [In Spanish]

Trujillo, F., Caicedo D., Diazgranados M. C. (2014). Plan de acción nacional para la conservación de los mamíferos acuáticos de Colombia (PAN mamíferos Colombia). Bogotá: Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible, Fundación Omacha, Conservación Internacional y WWF. [In Spanish]

Van Vliet, N., Quiceno, M., Moreno, J., Cruz, D., Fa J.E., Nasi R. (2016). Is urban bushmeat trade in Colombia really insignificant? Oryx. 51(2): 305-314

Resumé: Notes Sur La Loutre À Longue Queue (Lontra Longicaudis), La Chasse, Une Menace Possible Sous-Estimée En Colombie

Depuis que la chasse à la loutre à longue queue (Lontra longicaudis) a été légalement interdite en 1973 en Colombie, elle n'est plus considérée comme une préoccupation de conservation hautement prioritaire dans le pays. L’espèce est toujours classée comme vulnérable en Colombie, mais la Liste Rouge National des Mammifères et le plan d’action national pour la conservation des mammifères aquatiques en Colombie ne prennent en compte aucune utilisation de l’espèce, sauf comme animal de compagnie (une activité illégale en Colombie). Une enquête préliminaire visant à identifier les activités de chasse actuelles a été menée auprès d’instituts de recherche en biologie, d’ONG de défense de l’environnement, de professeurs d’université et d’autorités régionales de l’environnement, afin d’identifier la chasse actuelle dans les cinq écorégions de Colombie. L’ensemble des résultats dans les écorégions montrent que les principales raisons de chasser les loutres à longue queue sont : de les prendre comme animal de compagnie (29%), d’utiliser leur peau (24%) et la viande de brousse (22%). Ces résultats constituent une base pour rassembler davantage d'informations sur la chasse à la loutre à longue queue en Colombie

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Notas sobre la Caza de la Nutria Neotropical (Lontra Longicaudis), una Amenaza Posiblemente Subestimada en Colombia

Desde que la caza de la Nutria Neotropical (Lontra longicaudis) fue legalmente prohibida en 1973 en Colombia, ya no es considerada como una preocupación de conservación de alta prioridad en el país. La especie aún está clasificada como Vulnerable en el país, pero la Lista Roja Nacional de Mamíferos y el Plan de acción nacional para la conservación de los mamíferos acuáticos de Colombia no consideran ningún uso de la especie aparte de la tenencia como mascota (actividad ilegal en Colombia). Un relevamiento preliminar para identificar la actividad actual de caza fue conducido entre profesionales de instituciones de investigación biológica, ONGs ambientales, profesores universitarios y autoridades ambientales regionales, en cinco ecoregiones de Colombia. Los resultados globales de todas las ecoregiones muestran que las principales razones detrás de la caza de nutrias Neotropicales son: tenencia como mascota (29%), uso de la piel (24%) y uso de la carne (22%). Los resultados crean una base para colectar más información sobre la caza de nutrias Neotropicales en Colombia.

Vuelva a la tapa