IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Volume 39 Issue 1 (February 2022)

Citation: Rihadini, R., Appel, A., Handono, C.D., and Febrianto, I. (2022). First Photographic Records of the Small-Clawed Otter Aonyx cinereus (Illiger, 1815) in Eastern Java, Indonesia. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 39 (1): 3 - 15

First Photographic Records of the Small-Clawed Otter Aonyx cinereus (Illiger, 1815) in Eastern Java, Indonesia

Ragil Rihadini1, Angie Appel2*, Cipto Dwi Handono1, and Iwan Febrianto1

1Yayasan Eksai, Kutisari St. I no. 19, Surabaya 60291, Indonesia

2 Wild Cat Network, 56470 Bad Marienberg, Germany

*Corresponding Author Email: angie@wild-katze.org

(Received 31st May 2021, accepted 29th August 2021)

Abstract: The knowledge about the distribution of the Small-clawed Otter Aonyx cinereus on the Indonesian island of Java largely dates to the 20th century. We present the easternmost photographic evidence for its presence on Java. A camera trapping survey in 2018 yielded 28 notionally independent events of the Small-clawed Otter in a mangrove ecotourism site located east of the city of Surabaya. Most of these events show solitary individuals at night. Two duos were recorded in fishponds, and family groups between mid-November and end of December. The mangrove habitat along the coastline of this site is polluted by plastic waste, and microplastic entered the food chain through molluscs and fish, the main prey of the Small-clawed Otter. Further surveys are warranted to determine the distribution and conservation needs of the Small-clawed Otter in coastal wetlands of eastern Java..

Keywords: Wonorejo Mangroves, camera trapping, coastal wetland

INTRODUCTION

The Small-clawed Otter Aonyx cinereus has an extensive geographic range in subtropical and tropical Asian wetlands (Wright et al., 2015). Since the early 20th century, wetlands have been imperilled by large-scale conversions for agriculture and aquaculture, as well as construction of industrial and hydropower plants (Gopal, 2013; Davidson, 2014; Dixon et al., 2016). This habitat loss coupled with unsustainable over-hunting led to the decline of the global Small-clawed Otter population, and it is therefore listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (Wright et al., 2015). Repeated records of Small-clawed Otter pups offered alive in Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia indicate that the illegal pet trade is a major driver for unsustainable hunting (Shepherd and Tansom, 2013; Gomez and Bouhuys, 2017; Gomez and Bouhuys, 2018; Siriwat and Nijman, 2018).

The Small-clawed Otter has been known to occur on Java since the early 19th century (Illiger, 1815). It was commonly encountered in agricultural, urban and semi-urban environments on Java until at least the early 20th century but was intensively hunted and considered a pest to commercial fisheries (Meijaard, 2014). In western Java, it inhabits aquaculture sites along the coast, in creeks, irrigation channels and rice fields (Melisch et al., 1994). It was also sighted near the drainage system in southern Jakarta (Meijaard, 2014). As it is threatened by pollution and conversion of natural wetlands, it was proposed to be protected under Indonesian law in 1994 (Melisch et al., 1994). Since then, several authors reported live Small-clawed Otters offered for sale in Indonesian wildlife markets and social media platforms (Aadrean, 2013; Gomez et al., 2016; Gomez and Bouhuys, 2017; Gomez and Bouhuys, 2018; Gomez et al., 2019). Despite these reports, the Small-clawed Otter had still not received formal protection in the country by 2018 (Gomez and Shepherd, 2018). The IUCN Otter Specialist Group called for a long-term program to evaluate the status and dynamics of the Small-clawed Otter in human-altered wetland habitats in Indonesia (Duplaix and Savage, 2018).

From July 2018 to January 2019, we conducted a camera trapping survey in a coastal wetland located east of Surabaya. This survey yielded the first photographic evidence for the presence of the Small-clawed Otter along the northern coast of eastern Java.

STUDY AREA

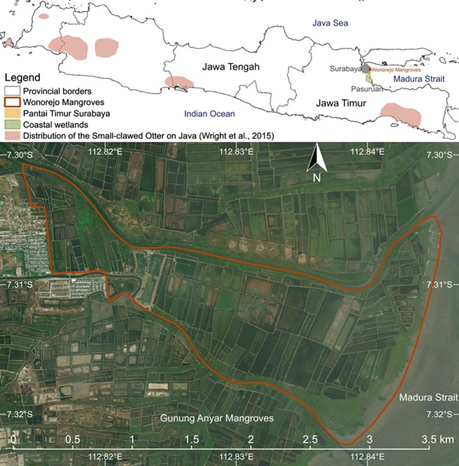

The Wonorejo Mangroves are located at the eastern outskirts of Surabaya in the province Jawa Timur (Prasita, 2015). They are bounded by the estuaries of the rivers Wonorejo in the north and Avuur in the south, both emptying into the Madura Strait at 7.304°S, 112.845°E and 7.322°S, 112.838°E, respectively (Fig. 1). They comprise about 300 ha of mangrove swamps and brackish aquaculture ponds (Fig. 2), latter varying in size from 0.3 ha to 8.5 ha. This area was designated as an ecotourism site in 2010 (Murtini et al., 2018) and forms part of a Mangrove Conservation Area (Prasita, 2015). The city government of Surabaya initiated a mangrove rehabilitation program (Hakim et al., 2017) and bought five abandoned fishponds in the Wonorejo Mangroves of about 13 ha in total, which are being renaturalised (Management team of the Mangrove Information Center in Gunung Anyar Mangroves, personal communication 24 July 2018). The other ponds are owned and managed by small cooperatives and families who cultivate Milkfish Chanos chanos, Catfish Clarias batrachus, Tilapia Oreochromis mossambicus, Asian Sea Bass Lates calcarifer and mud crabs Scylla. There is no permanent house in this area. Pond workers use small shacks by day, if and when they need to carry out maintenance work such as regulating inflow of water, harvesting and restocking ponds.

Contiguous mangroves cum aquaculture ponds straddle along the coast over at least 225 km2 up to the city of Pasuruan (Prasita, 2015; Maryantika and Lin, 2017). A part of 56 km2 was designated as the Important Bird Area (IBA) Pantai Timur Surabaya, a resting and breeding site for migratory waterbirds (BirdLife International, 2018). A part of the mangrove swamps to the west of this IBA were converted between 1995 and 2015 to make way for the extension of the nearby airport (Maryantika and Lin, 2017).

The climate in the entire region is dominated by the Southeast Asian monsoon that brings high humidity during the wet season from November to April (Aldrian and Djamil, 2008). Monthly rainfall ranges from 105 mm in November to 327 mm in January and decreases to 101 mm in June (WWIS, 2020). Dry southerly winds prevail during July to October (Aldrian and Djamil, 2008). This dry season exhibits a total of 19 rainy days on average with a total mean rainfall of 81 mm (WWIS, 2020). Temperatures range from a daily minimum of 22.5 °C in August to a daily maximum of 33.4 °C in October (WWIS, 2020)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used six Enkeeo PH730 camera traps and set them to be active for 24 hours per day taking three photographs within an interval of one second followed by a video of 20 seconds. We mounted one camera trap per station 30–45 cm above ground without attractant and deployed the stations opportunistically on dykes between ponds. Where accessible, we also deployed camera traps in mangrove patches along Avuur River and in silted-up areas inside ponds. We kept the stations for 6–117 days and determined their coordinates using the GPS function of a mobile phone, model Xiaomi Redmi 4X, which was set to WGS84 datum. Camera traps were deployed, checked and moved in the mornings, so that we define a camera trap day as a full 24-hour day.

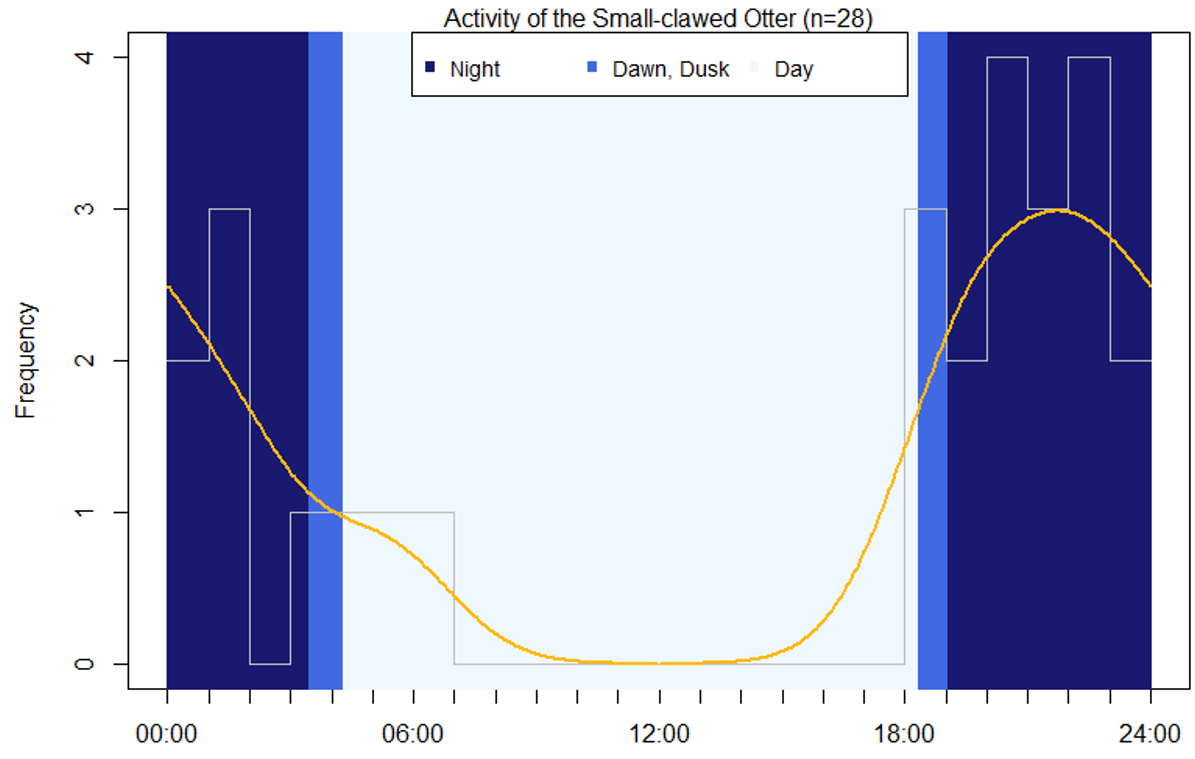

We consider consecutive photographs of the same species within 30 minutes to be a notionally independent event. We relied on the data provided by TDAS (2021) to determine the times of night, dawn, day and dusk of these notionally independent events. To analyse and visualize the activity pattern of the Small-clawed Otter in our study area we used the package ‘activity’ in the statistical software R (Rowcliffe et al., 2014; R Development Core Team, 2021).

RESULTS

The camera trapping survey was carried out from 18 July 2018 to 6 January 2019 in 14 stations. The total sampling effort of 519 camera trap days yielded 28 notionally independent events (NIE) of the Small-clawed Otter between 12 September and 29 December in six stations. It was photographed on dykes between ponds in four stations, on the muddy bank of a pond in one and swimming in another station (Fig. 3). Solitary individuals were recorded in 21 NIE, groups of three to five individuals in five NIE (Fig. 4), and duos in two NIE. Three NIE were taken in early mornings shortly after sunrise between 5:30 and 6:11 h, and the remaining after dark between 18:08 and 03:00 h (Fig. 5).

Other wildlife photographed in the study area comprises Small Indian Civet Viverricula indica, Common Palm Civet Paradoxurus hermaphroditus, Javan Mongoose Urva javanicus, Sunda Leopard Cat Prionailurus javanensis, Long-tailed Macaque Macaca fascicularis, Asian Water Monitor Varanus salvator, rodents, birds and mud crabs.

DISCUSSION

Our survey yielded the first photographic evidence for the presence of the Small-clawed Otter in eastern Java. To date, its distribution in Java has been thought to be discontinuous, limited to widely spaced areas in western Java and in the south of the provinces Jawa Tengah and Jawa Timur (Wright et al., 2015; Fig. 1). Previous records on the island were based on reports by local people (Yossa et al., 1991; Husodo et al., 2019), tracks and spraints found in the vicinity of slow-flowing rivers, narrow mountain creeks, irrigation channels and rice fields, all in western Java (Melisch et al., 1996; Megantara et al., 2019). Live individuals were sighted near drainage channels in southern Jakarta (Meijaard, 2014) and photographed by camera traps in Cisokan (Husodo et al. 2019), both also in western Java. Tracks, faeces and empty nests found along six rivers in Batang Regency of Jawa Tengah were attributed to the Small-Clawed Otter (Dwijayanti et al. 2021).

Elsewhere in Southeast Asia, it inhabits rice fields (Foster-Turley, 1992; Aadrean et al., 2011; Aadrean and Usio, 2020; Andreska et al., 2021) and peat swamp forest (Cheyne et al., 2010; Kanchanasaka and Duplaix, 2011). We did not find any evidence for the Small-clawed Otter using rice fields outside Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra and Java. The lack of such records in India may be due to the dearth of surveys in this habitat type (Arjun Srivathsa, in litt. 4 March 2021; Katrina Fernandez, in litt. 5 March 2021). It has been recorded widely across its range in the vicinity of freshwater lowland and montane streams (Kruuk et al., 1994; Castro and Dolorosa, 2008;Hon et al., 2010; Perinchery et al., 2011; Prakash et al., 2012; Naniwadekar et al., 2013; Mohapatra et al., 2014; Punjabi et al., 2014; Raha and Hussain, 2016; Krupa et al., 2017; Nikhil and Nameer, 2017; McCann and Pawlowski, 2017; Mudappa et al., 2018; Sreekumar and Nameer, 2018; Sanghamithra and Nameer 2018; Li et al., 2019; Tantipisanuh et al., 2019; Marler et al., 2019; Menzies and Rao, 2021). Published sightings in mangrove habitat are limited to Similajau National Park in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo (Duckworth, 1997) and the Sundarbans Mangroves in Bangladesh (Aziz, 2018). In southwestern Thailand, it was also photographed in mangrove swamps (Tantipisanuh et al., 2019).

In view of the small size of our study area, all 28 NIE of the Small-clawed Otter presumably show the same individuals, comprising two adults between 12 September and 9 November and a family group between 13 November and 29 December 2018. Camera trap photographs showing one to three individuals were often reported (Naniwadekar et al., 2013; Punjabi et al., 2014; Krupa et al., 2017; Nikhil and Nameer, 2017; Mudappa et al., 2018; Sanghamithra and Nameer, 2018; Li et al., 2019). Groups of four to five individuals were photographed in three protected areas (McCann and Pawlowski, 2017; Allen et al., 2019; Marler et al., 2019). Willcox et al. (2017) reported a maximum group size of eight individuals in U Minh Ha National Park, Vietnam. A group of about nine individuals was documented in a coastal wetland in western Java (Erwin Wilianto in litt., 17 November 2016), and also near the Andaman coast in southern Thailand (Tantipisanuh et al., 2019). In contrast, Aziz (2018) observed groups of up to 12 members apart from solitary individuals and duos between November and March.

The activity pattern of the Small-Clawed Otter observed in our study area is only a first indication and may not be representative for its general behaviour. However, this pattern fits with its nocturnal and crepuscular activity in habitats that are frequented by people (Foster-Turley, 1992; Prakash et al., 2012; Krupa et al., 2017; Nikhil and Nameer, 2017; Sreekumar and Nameer, 2018; Li et al., 2019). In undisturbed protected areas, it was also photographed by day (Mohapatra et al., 2014; McCann and Pawlowski, 2017; Willcox et al., 2017; Aziz, 2018; Sanghamithra and Nameer, 2018; Allen et al., 2019; Marler et al., 2019; Tantipisanuh et al., 2019; Menzies and Rao, 2021).

Low and dense vegetation is considered important as shelter for the Small-clawed Otter (Foster-Turley, 1992; Melisch et al., 1996; Prakash et al., 2012). In the Wonorejo Mangroves, dense vegetation is present off trails and in silted-up areas inside abandoned ponds. Potential prey of the Small-clawed Otter includes crustaceans, mudskippers Periophthalmus and fish, which elsewhere have been found to constitute its staple diet (Foster-Turley, 1992; Kruuk et al., 1994; Melisch et al., 1996; Hon et al., 2010; Kanchanasaka and Duplaix, 2011; Aziz, 2018). On the other hand, the concentration of heavy metals in flesh of mud crabs in the Wonorejo River is slightly below the threshold recommended for human consumption (Ardianto et al., 2019). The coastline of the Wonorejo Mangroves is polluted by plastic waste, both macro- and microplastic (Kurniawan et al., 2019; Firdaus et al., 2020). Marine organisms ingest microplastic, which possibly acts as a vector for the chemical transfer of pollutants within the food chain (Teuten et al., 2007). Microplastic was found in molluscs and fish in other parts of the Javan coastline (Lestari and Trihadiningrum, 2019). Both heavy metals and microplastic are likely to be detrimental to the health of wildlife in the Wonorejo Mangroves. A strategy to clean up remnant mangrove patches from plastic waste is urgently required, and frequent manual cleanups are imperative. We consider it vital to monitor the water quality in estuaries and in ponds as a prerequisite for intervention in case the water quality deteriorates.

On Java, the Small-clawed Otter is primarily threatened by poaching for the pet trade (Aadrean, 2013; Gomez et al., 2019). Between November 2018 and January 2019, Gomez et al. (2019) traced 42 advertisements offering pups in the province of Jawa Timur alone that were posted on a social media platform, including 19 offers in Surabaya. The legal protection of the Small-clawed Otter in Indonesia is long overdue (Melisch et al., 1994; Gomez and Shepherd, 2018; Duplaix and Savage, 2018; Gomez et al., 2019). Tough penalties must be adopted and enforced to deter catching and trading of otters in the country. We also recommend monitoring of social media platforms and wildlife markets in Surabaya and neighbouring cities. As already stipulated by Duplaix and Savage (2018), it is equally essential to raise public awareness for the challenges to safeguard the Small-clawed Otter.

Given the extent of the coastal wetland between the cities of Surabaya and Pasuruan, this broader area may constitute an important refuge for the Small-clawed Otter on Java. Systematic surveys are urgently needed in this area and adjacent agricultural fields to the southwest to acquire baseline data on its population size, threats and conservation needs. We also recommend to explore river valleys farther south that might constitute corridors to the population along the southern coast of Jawa Timur.

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to The Aspinall Foundation, Wong Chia Lee and Poo Lin Stefano Wong for providing much needed equipment. We thank officers of the Wildlife and Nature Conservation Agency of Jawa Timur who kindly provided valuable information about mangrove swamps in northeastern Java. We also thank Nicole Duplaix for her assistance in identifying the species. We are much obliged to Will Duckworth for inspiring discussions and suggestions that greatly improved our manuscript.

REFERENCES

Aadrean and Usio, N. (2020). Spatiotemporal patterns of latrine-site use by Small-Clawed Otters in a heterogeneous rice field landscape. Mammal Study 45(2): 103–110. https://doi.org/10.3106/ms2019-0031

Aadrean (2013). An investigation of otters trading as pet in Indonesian online markets. Jurnal Biologika 2: 1-6.

Aadrean, Novarino, W. and Jabang (2011). A record of small-clawed Otters (Aonyx cinereus) foraging on an invasive pest species, Golden Apple Snails (Pomacea canaliculata) in a West Sumatra rice field. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 28(1): 34–38. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume28/Aadrean_et_al_2011.html

Aldrian, E. and Djamil, Y.S. (2008). Spatio‐temporal climatic change of rainfall in East Java Indonesia. International Journal of Climatology 28(4): 435–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1543

Allen, M.L., Sibarani, M.C. and Utoyo, L. (2019). The first record of a wild hypopigmented Oriental Small-clawed Otter (Aonyx cinereus). Ecotropica 21: 201904. https://www.ecotropica.eu/index.php/ecotropica/article/view/12

Andreska, F., Novarino, W., Nurdin, J. and Aadrean (2021). Relationship between temporal environment factors and diet composition of Small-Clawed Otter (Aonyx cinereus) in heterogeneous paddy fields landscape in Sumatra, Indonesia. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 38(2): 106–116. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume38/Andraska_et_al_2021.html

Ardianto, N., Prayogo, P. and Sahidu, A.M. (2019). Analysis of Heavy Metal Cadmium (Cd) Content on Mud Crab (Scylla sp.) at Wonorejo River Surabaya. Omni-Akuatika 15(1): 75–80. http://dx.doi.org/10.20884/1.oa.2019.15.1.585

Aziz, M.A. (2018). Notes on population status and feeding behaviour of Asian Small-clawed Otter (Aonyx cinereus) in the Sundarbans Mangrove Forest of Bangladesh. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 35(1): 3–10. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume35/Aziz_2018.html

BirdLife International (2018). Important Bird Areas factsheet: Pantai Timur Surabaya. Downloaded from http://datazone.birdlife.org/site/factsheet/pantai-timur-surabaya-iba-indonesia on 25 August 2018.

Castro, L.S.G. and Dolorosa, R.G. (2008). Conservation status of the Asian Small-clawed Otter Amblonyx cinereus (Illiger, 1815) in Palawan, Philippines. The Philippine Scientist 43: 69–76.

Cheyne, S.M., Husson, S.J., Chadwick, R.J. and Macdonald, D.W. (2010). Diversity and activity of small carnivores of the Sabangau Peat-swamp Forest, Indonesian Borneo. Small Carnivore Conservation 43: 1–7.

Davidson, N.C. (2014). How much wetland has the world lost? Long-term and recent trends in global wetland area. Marine and Freshwater Research 65(10): 934–941. https://doi.org/10.1071/MF14173

Dixon, M.J.R., Loh, J., Davidson, N.C., Beltrame, Freeman, C. R. and Walpole, M. (2016). Tracking global change in ecosystem area: the Wetland Extent Trends index. Biological Conservation 193: 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.10.023

Duckworth, J.W. (1997). Mammals in Similajau National Park, Sarawak, in 1995. The Sarawak Museum Journal 51: 171–192.

Duplaix, N. and Savage, M. (2018). Small-clawed Otter Aonyx cinereus. Pp. 34–39 in: The Global Otter Conservation Strategy. IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group, Salem, Oregon, USA.

Dwijayanti, E., Inayah, N., Farida, W.R., Sulistyadi, E. and Saputra, S. (2021). Rapid survey for population, commercial trade of Small-Clawed Otter (Aonyx cinereus Illiger, 1815) in Java and preliminary assessment of potential bacterial zoonoses. Acta Veterinaria Indonesiana Special Issue (May): 86–94.

Firdaus, M., Trihadiningrum, Y. and Lestari, P. (2020). Microplastic pollution in the sediment of Jagir estuary, Surabaya City, Indonesia. Marine Pollution Bulletin 150: 110790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110790

Foster-Turley, P. (1992). Conservation ecology of sympatric Asian otters Aonyx cinerea and Lutra perspicillata (Ph.D. Dissertation). Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida.

Gomez, L. and Bouhuys, J. (2017). Recent seizures of live otters in Southeast Asia. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 34(2): 81–83. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume34/Gomez_Bouhuys_2017.html

Gomez, L. and Bouhuys, J. (2018). Illegal Otter Trade in Southeast Asia. TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia.

Gomez, L. and Shepherd, C.R. (2018). Smooth-coated Otter Lutrogale perspicillata receives formal protection in Indonesia, but Small-clawed Otter Aonyx cinereus does not. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 35(2): 128–130. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume35/Gomez_Shepherd_2018.html

Gomez, L., Leupen, B.T.C., Theng, M., Fernandez, K. and Savage, M. (2016). Illegal Otter Trade: An analysis of seizures in selected Asian countries (1980–2015). TRAFFIC. Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia.

Gomez, L., Shepherd, C.R. and Morgan, J. (2019). Improved legislation and stronger enforcement actions needed as the online otter trade in Indonesia continues. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 36(2): 64–70. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume36/Gomez_et_al_2019.html

Gopal, B. (2013). Future of wetlands in tropical and subtropical Asia, especially in the face of climate change. Aquatic Sciences 75(1): 39−61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-011-0247-y

Hakim, L., Siswanto, D. and Nakagoshi, N. (2017). Mangrove conservation in East Java: The ecotourism development perspectives. Journal of Tropical Life Science 7(3): 277–285. https://doi.org/10.11594/jtls.07.03.14

Hon, N., Neak, P., Khov, V. and Cheat, V. (2010). Food and habitat of Asian Small-clawed Otters in northeastern Cambodia. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 27(1): 12–23. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume27/Hon_et_al_2010.html

Husodo, T., Febrianto, P., Megantara, E.N., Shanida, S.S. and Pujianto, M.P. (2019). Diversity of mammals in forest patches of Cisokan, Cianjur, West Java, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 20(5): 1281–1288. DOI: https://doi.org/10.13057/biodiv/d200518

Illiger, C. (1815). Überblick der Säugethiere nach ihrer Verteilung über die Welttheile. Abhandlungen der Königlichen Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin 1804−1811: 39−159.

Kanchanasaka, B. and Duplaix, N. (2011). Food habits of the Hairy-nosed Otter (Lutra sumatrana) and the Small-clawed Otter (Aonyx cinereus) in Pru Toa Daeng Peat Swamp Forest, Southern Thailand. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 28A: 139−161.

Krupa, H., Borker, A. and Gopal, A .(2017). Photographic record of sympatry between Asian Small-Clawed Otter and Smooth-coated Otter in the Northern Western Ghats, India. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 34(1): 51−57. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume28A/Kanchanasaka_Duplaix_2011.html

Kruuk, H., Kanchanasaka, B., O'Sullivian, S. and Wanghongsa, S. (1994). Niche separation in three sympatric otters Lutra perspicillata, Lutra lutra and Aonyx cinerea in Huai Kha Khaeng, Thailand. Biological Conservation 69: 115−210. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(94)90334-4

Kurniawan, S.B. and Imron, M.F. (2019). The effect of tidal fluctuation on the accumulation of plastic debris in the Wonorejo River Estuary, Surabaya, Indonesia. Environmental Technology & Innovation 15: 100420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2019.100420

Lestari, P. and Trihadiningrum, Y. (2019). The impact of improper solid waste management to plastic pollution in Indonesian coast and marine environment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 149: 110505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110505

Li, F., Luo, L. and Chan, B.P.L. (2019). Notes on distribution, status and ecology of Asian Small-Clawed Otter (Aonyx cinereus) in Diaoluoshan National Nature Reserve, Hainan Island, China. Proceedings of the14th International Otter Congress, IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 36A: 39–46. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume36A/Li_et_al_2019.html

Marler, P.N., Calago, S., Ragon, M. and Castro, L.S.G. (2019). Camera trap survey of mammals in Cleopatra’s Needle Critical Habitat in Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines. Journal of Threatened Taxa 11(13): 14631–14642. https://doi.org/10.11609/jott.5013.11.13.14631-14642

Maryantika, N. and Lin, C. (2017). Exploring changes of land use and mangrove distribution in the economic area of Sidoarjo District, East Java using multi-temporal Landsat images. Information Processing in Agriculture 4(4): 321–332. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.inpa.2017.06.003

McCann, G. and Pawlowski, K. (2017). Small carnivores’ records from Virachey National Park, north-east Cambodia. Small Carnivore Conservation 55: 26–41.

Megantara, E.N., Shanida, S.S., Husodo, T., Febrianto, P., Pujianto, M.P. and Hendrawan, R. (2019). Habitat of mammals in West Java, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 20(11): 3380–3390. https://doi.org/10.13057/biodiv/d201135

Meijaard, E. (2014). A review of historical habitat and threats of Small-clawed Otter on Java. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 31: 40–44. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume31/Meijaard_2014.html

Melisch, R., Asmoro, P. B. and Kusumawardhami, L. (1994). Major steps taken towards otter conservation in Indonesia. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 10: 21–24. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume10/Melisch_et_al_1994.html

Melisch, R., Kusumawardhani, L., Asmoro, P.B. and Lubis, I.R. (1996). The otters of West Java – a survey of their distribution and habitat use and a strategy towards a species conservation programme. Wetlands International, Directorate General of Forest Protection and Nature Conservation, Bogor, Indonesia.

Menzies, R.K. and Rao, M. (2021). Incidental sightings of the Vulnerable Asian Small-Clawed Otter (Aonyx cinereus) in Assam, India: Current and future threats. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 38(1): 36–42. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume38/Menzies_Rao_2021.html

Mohapatra, P.P., Palei, H.S. and Hussain, S.A. (2014). Occurrence of Asian Small-clawed Otter Aonyx cinereus (Illiger, 1815) in Eastern India. Current Science 107(3): 367–370.

Mudappa, D., Prakash, N., Pawar, P., Srinivasan, K., Ram, M.S., Kittur, S. and Umapathy, G. (2018). First Record of Eurasian Otter Lutra lutra in the Anamalai Hills, Southern Western Ghats, India. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 35(1): 47–56. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume35/Mudappa_et_al_2018.html

Murtini, S., Astina, I.K. and Utomo, D.H. (2018). SWOT analysis for the development strategy of mangrove ecotourism in Wonorejo, Indonesia. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 9(5): 129.

Naniwadekar, R., Shukla, U., Viswanathan, A. and Datta, A. (2013). Records of small carnivores from in and around Namdapha Tiger Reserve, Arunachal Pradesh, India. Small Carnivore Conservation 49: 1–8.

Nikhil, S. and Nameer, P.O. (2017). Small carnivores of the montane forests of Eravikulam National Park in the Western Ghats, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa 9(11): 10880–10885. http://doi.org/10.11609/jott.2211.9.11.10880-10885

Perinchery, A., Jathanna, D. and Kumar, A. (2011). Factors determining occupancy and habitat use by Asian small-clawed Otters in the Western Ghats, India. Journal of Mammalogy 92(4): 796–802. https://doi.org/10.1644/10-MAMM-A-323.1

Prakash, N., Mudappa, D., Raman, T.S. and Kumar, A. (2012). Conservation of the Asian Small-clawed Otter (Aonyx cinereus) in human-modified landscapes, Western Ghats, India. Tropical Conservation Science 5(1): 67–78.

Prasita, V.D. (2015). Determination of shoreline changes from 2002 to 2014 in the Mangrove Conservation Areas of Pamurbaya using GIS. Procedia Earth and Planetary Science 14: 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeps.2015.07.081

Punjabi, G.A., Borker, A. S., Mhetar, F., Joshi, D., Kulkarni, R., Alave, S.K. and Rao, M.K. (2014). Recent records of Stripe-necked Mongoose Herpestes vitticollis and Asian Small-clawed Otter Aonyx cinereus from the north Western Ghats, India. Small Carnivore Conservation 51: 51–55.

R Development Core Team (2021). R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available online at https://www.R-project.org/.

Raha, A. and Hussain, S.A. (2016). Factors affecting habitat selection by three sympatric otter species in the southern Western Ghats, India. Acta Ecologica Sinica 36(1): 45–49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chnaes.2015.12.002

Rowcliffe, J.M., Kays, R., Kranstauber, B., Carbone, C. and Jansen, P.A. (2014). Quantifying levels of animal activity using camera trap data. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 5(11): 1170–1179. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12278

Sanghamithra, D. and Nameer, P. O. (2018). Small carnivores of Silent Valley National Park, Kerala, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa 10(8): 12091–12097. https://doi.org/10.11609/jott.2992.10.8.12091-12097

Shepherd, C.R. and Tansom, P. (2013). Seizure of live otters in Bangkok Airport, Thailand. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 30(1): 37–38. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume30/Shepherd_Tansom_2013.html

Siriwat, P. and Nijman, V. (2018). Illegal pet trade on social media as an emerging impediment to the conservation of Asian otters species. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity 11(4): 469–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japb.2018.09.004

Sreekumar, E.R. and Nameer, P.O. (2018). Small carnivores of Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary, the southern Western Ghats, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa 10(1): 11218–11225. http://doi.org/10.11609/jott.3651.10.1.11218-11225

Tantipisanuh, N., Chutipong, W., Ngoprasert, D., Klinsawat, W., Kamjing, A., Phosri, K. and Wongtung, P. (2019). Area prioritization for otter conservation in wetlands areas of southern Thailand – Andaman Coast. Presentation given at the 40th Thailand Wildlife Seminar: can people and wildlife coexist? 12–13 December 2019, Bangkok, Thailand, 26 pp.

TDAS (2021). Surabaya, East Java, Indonesia - Sunrise, Sunset, and Daylength. Time and Date AS, Stavanger, Norway. Electronic version at https://www.timeanddate.com/sun/@-7.31096,112.82899 accessed on 2 May 2021.

Teuten, E.L., Rowland, S.J., Galloway, T.S. and Thompson, R.C. (2007). Potential for plastics to transport hydrophobic contaminants. Environmental Science and Technology 41: 7759–7764. http://doi.org/10.1021/es071737s

Willcox, D., Bull, R., Nguyen V.N., Tran Q.P. and Nguyen V.T. (2017). Small carnivore records from the U Minh Wetlands, Vietnam. Small Carnivore Conservation 55: 4–25.

Wright, L., de Silva, P., Chan, B. and Reza Lubis, I. (2015). Aonyx cinereus. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T44166A21939068. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T44166A21939068.en Downloaded on 8 February 2021.

WWIS (2020). World Weather Information Service: Surabaya. World Meteorological Organization, Hong Kong Observatory, Hong Kong. Electronic version at https://worldweather.wmo.int/en/city.html?cityId=648 accessed on 15 January 2021.

Yossa, I., Navy, P., Dolly, P., Yudha, N., Aswar and Yosias, M. (1991). Survey of the carnivores of Gunung Halimun Nature Reserve, Java. Small Carnivore Conservation 5: 3.

Abstrak: Catatan Fotografi Pertama Berang-Berang Cakar Kecil Aonyx Cinereus (Illiger, 1815) Di Jawa Timur, Indonesia

Informasi mengenai distribusi Berang-berang Cakar Kecil Aonyx cinereus di pulau Jawa, Indonesia sebagian besar berasal dari abad ke-20. Kami menyajikan bukti fotografi kehadiran Berang-berang Cakar Kecil di sisi paling timur Pulau Jawa. Dari hasil survei kamera trap di tahun 2018, diperoleh 28 kejadian independen dari Berang-berang Cakar Kecil di wilayah ekowisata mangrove yang berlokasi di sisi timur kota Surabaya. Kebanyakan dari kejadian yang tertangkap oleh kamera trap menunjukkan individu soliter pada malam hari. Dua pasangan terekam di tambak ikan, dan grup keluarga terekam di pertengahan November dan akhir Desember. Habitat mangrove di sepanjang garis pantai pada lokasi ini tercemar oleh sampah plastic, dan mikroplastik memasuki rantai makanan melalui moluska dan ikan, makanan utama dari Berang-berang Cakar Kecil. Survei lebih lanjut diperlukan untuk menentukan distribusi dan kebutuhan konservasi spesies Berang-berang Cakar Kecil di pesisir lahan basah Jawa bagian timur.

Kembali ke awal

Résumé: Premiers Preuves Photographiques de la Loutre Cendrée Aonyx cinereus (Illiger, 1815) dans l’Est de Java, Indonésie

La connaissance sur la distribution de la Loutre Cendrée Aonyx cinereus sur l’île indonésienne de Java remonte en grande partie au 20ième siècle. Nous présentons les preuves photographiques les plus orientales de sa présence à Java. Une enquête par piéges photographiques en 2018 a révélé 28 événements théoriquement indépendants de la Loutre Cendrée dans un site écotouristique de mangrove situé à l’est de la ville de Surabaya. La plupart de ces événements montrent des individus solitaires durant la nuit. Deux duos ont été enregistrés dans des étangs piscicoles et des groupes familiaux entre la mi-Novembre et la fin Décembre. L’habitat de mangrove le long du littoral de ce site est pollué par les déchets plastiques, et le microplastique est entré dans la chaîne alimentaire par des mollusques et des poissons, lesquelles sont les principales proies de la Loutre Cendrée. D’autres études sont nécessaires pour déterminer la distribution et les besoins de conservation de la Loutre Cendrée dans les zones humides littorales de l’st de Java.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Primeros Registros Fotográficos de la Nutria de Uñas Pequeñas Asiática Aonyx Cinereus (Illiger, 1815) en Java Oriental, Indonesia

El conocimiento sobre la distribución de la Nutria de Uñas Pequeñas Asiática Aonyx cinereus en la isla indonesia de Java, mayormente data del siglo 20. Presentamos la evidencia fotográfica más oriental de su presencia en Java. Un relevamiento con cámaras-trampa en 2018 produjo 28 eventos independientes de Nutria de Uñas Pequeñas en un sitio de ecoturismo ubicado al este de la ciudad de Surabaya. La mayoría de estos eventos muestran individuos solitarios, por la noche. Dos dúos fueron registrados en estanques para peces, y grupos familiares entre mediados de Noviembre y final de Diciembre. El hábitat de manglares que bordea la costa de éste sitio está contaminado por desechos plásticos, y los microplásticos ingresaron a la cadena alimentaria a través de moluscos y peces, la presa principal de la Nutria de Uñas Pequeñas. Se justifica realizar relevamientos adicionales para determinar la distribución y necesidades de conservación de la Nutria de Uñas Pequeñas en los humedales costeros de Java oriental.

Vuelva a la tapa

Zusammenfassung: Erste Aufnahmen des Zwergsotters Aonyx cinereus (Illiger, 1815) im Osten von Java, Indonesien

Das Wissen über die Verbreitung des Zwergotters Aonyx cinereus auf der indonesischen Insel Java datiert zum größten Teil aus dem 20. Jahrhundert. Wir stellen die östlichsten fotografischen Belege für seine Anwesenheit auf Java vor. Eine Untersuchung mithilfe von Kamerafallen in 2018 erbrachte 28 vermutlich unabhängige Nachweise des Zwergotters in einem ökotouristischen Mangrovengebiet östlich der Stadt Surabaya. Die meisten dieser Nachweise zeigen einzelne Individuen bei Nacht. Zwei Duos wurden in Fischteichen fotografiert, und Familiengruppen zwischen Mitte November und Ende Dezember. Das Mangrovengebiet entlang der Küste ist mit Plastikmüll verschmutzt, und in die Nahrungskette drang Mikroplastik durch Weichtiere und Fisch ein, die Hauptbeute des Zwergotters. Weitere Untersuchungen sind nötig um die Verbreitung des Zwergotters in küstennahen Feuchtgebieten im Osten Javas zu ermitteln und erforderliche Naturschutzmaßnahmen zu bestimmen.

Zurück zum Anfang