IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Volume 41 Issue 1 (March 2024)

Citation: Ramírez Arango, K.J., Delgado Puentes, S., Aristizábal Páez, O.L., and Vélez García, J.F. (2024). First Report of the Origin and Distribution of the Brachial Plexus in the Scapular and Brachial Regions in a Neotropical River Otter (Lontra longicaudis). IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull., 41 (1): 31 - 45

First Report of the Origin and Distribution of the Brachial Plexus in the Scapular and Brachial Regions in a Neotropical River Otter (Lontra longicaudis)

Karla Johanna Ramírez Arango1*, Stephanie Delgado Puentes1, Omar Leonardo Aristizábal Páez1, and Juan Fernando Vélez García1, 2*

1Research group of Medicine and Surgery in Small Animals, Department of Animal Health, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Zootechnics, Universidad del Tolima, Ibagué. Colombia

2Postgraduate Program in Anatomy of the Domestic and Wild Animals, Department of Surgery, School of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

*Corresponding Author Email: jfvelezg@ut.edu.co

Received 2nd February 2023, accepted 6th October 2023

Abstract: The neotropical river otter (Lontra longicaudis) is a carnivoran species belonging to the family Mustelidae. There are no reports about the brachial plexus, and its knowledge is essential to clinical diagnoses and surgical procedures of the thoracic limb. Variations in the origin and distribution of the brachial plexus may exist among carnivoran species. Thus, the present study aimed to describe the origin of the brachial plexus and the distribution of its nerves in the scapular and brachial regions of L. longicaudis. One formaldehyde-fixed specimen of L. longicaudis was dissected. The brachial plexus originated from the last three cervical spinal nerves and the first two thoracic spinal nerves (C6-T2). The brachial plexus nerves and their distribution in the scapular and brachial regions of L. longicaudis were similar to those described in most carnivorans. However, differences were found, including two communicating branches (rami communicantes) from the nervus musculocutaneus to the nervus medianus, one proximal and one distal. The ramus communicans proximalis has also been found in other mustelids, while the ramus communicans distalis has not been found in other mustelids. Thus, the brachial plexus of L. longicaudis may present variations compared with other carnivorans.

Keywords:Anatomy, Carnivora, Mustelidae, Nerve, Neurology

INTRODUCTION

The Neotropical river otter (Lontra longicaudis) belongs taxonomically to the order Carnivora and the family Mustelidae (Nyakatura and Bininda-Emonds, 2012). The species has a geographic distribution range from northwestern Mexico to Uruguay and northeastern Argentina (Nivelo-Villavicencio et al., 2020). L. longicaudis is mainly found in habitats close to bodies of water, such as mangrove areas, lagoons, rivers, and wetlands (González-Christen et al., 2013; Mayor-Victoria and Botero-Botero, 2010). It is a medium-large species, with an average body mass in males of 16 kg and females of 13 kg (Gallo-Reynoso et al., 2013). They are adapted to move effectively in water since their thoracic and pelvic limbs are short and robust and present interdigital membranes between their digits (Emmons and Feer, 1997; Rheingantz et al., 2017). The hands are used to grasp food when held on the chest or socialize with the young (Mosquera-Guerra et al., 2018; Trujillo and Mosquera-Guerra, 2018). It has long vibrissae that act as indicators of current and water pressure changes to locate prey. It uses its long and broad tail to paddle in the water and to direct the body when swimming (Mosquera-Guerra et al., 2018). Its diet is based on small vertebrates, mainly fishes, although it can also eat insects and fruits (Mayor-Victoria and Botero-Botero, 2010; Rheingantz et al., 2017).

The brachial plexus is a network of nerves that innervate the thoracic limb and adjacent regions, allowing sensitivity and mobility of these anatomical regions (Liebich et al., 2020; Singh, 2018). In domestic carnivorans, it is formed mainly by the rami ventrales (ventral branches) of the last three cervical spinal nerves (C6, C7 and C8) and the first thoracic spinal nerve (T1) (Singh, 2018). However, occasionally, there may be a contribution from the fifth cervical nerve (C5) and the second thoracic nerve (T2) (Hermanson et al., 2020; Singh, 2018). In most reports on wild carnivorans, the contribution of C5 and T2 is not present (Barreto‐Mejía et al., 2022; Chagas et al., 2014; Demiraslan et al., 2015; Nur et al., 2020; Haligur and Ozkadif, 2021; Hermanson et al., 2020; Pinheiro et al., 2013, 2014; Souza-Junior et al., 2017, 2018; Souza et al., 2010). However, in representative species of the superfamily Musteloidea the contribution of both rami is common (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022; Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022; Vélez García et al., 2023).

L. longicaudis individuals may be in zoos or wildlife care centers (Restrepo et al., 2018). Knowledge of the brachial plexus would help to perform clinical and surgical procedures. Therefore, it is essential to determine the origin and distribution of the brachial plexus since it could be applied in a neurological exam (De Lahunta et al., 2020), locoregional blocks (Ansón et al., 2013; Mencalha et al., 2014; Skelding et al., 2018) and surgical procedures. Thus, this study aimed to describe the origin of the brachial plexus and the distribution of its nerves on the scapular and brachial muscles in L. longicaudis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

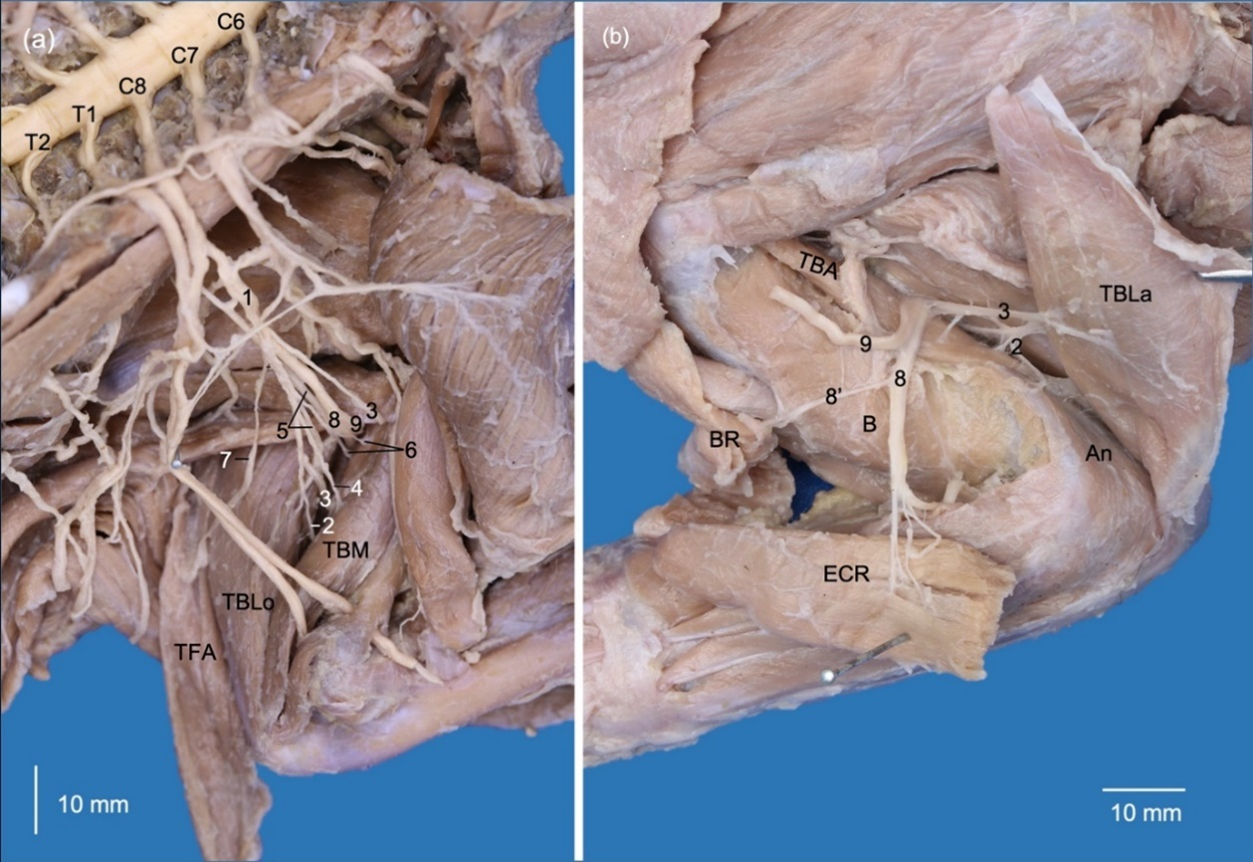

A male cadaver of L. longicaudis donated by the Corporación Autónoma Regional del Tolima (CORTOLIMA, Environmental Authority of Tolima, Colombia) to the Universidad del Tolima was used. The specimen had abdominal incisions due to the necroscopic study performed at the Wildlife Care Center of CORTOLIMA. The cadaver was conserved frozen, and after several days, it was defrosted and fixed with a solution of 10% formaldehyde and 5% glycerin via subcutaneous and intramuscular infiltrations. Subsequently, the cadaver was immersed and maintained in a container with 5% formaldehyde. The pectoral muscles were removed from their origins to review the neurovascular relations at the axillary region. Subsequently, the blood vessels, viscera (oesophagus, trachea, heart and lungs), and ventral neck muscles were removed to find the rami ventrales of the spinal nerves (Fig. 1). The anatomical description was based on the Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria (International Committee on Veterinary Gross Anatomical Nomenclature, 2017), and the origin of each nerve was reviewed, retracting the nerve proximally until the rami ventrales of the spinal nerves. Photographs were taken with a Canon T5i 18 MP camera associated with a Canon 60 mm macro lens and a Canon EOS 6D 20.2 MP camera associated with a Canon 100 lens. We only studied one specimen because it was a unique cadaver donated to the research project (Number 390116), which was performed between 2016 and 2022. In addition, this species is categorized as “Near threatened” by the International Union to Nature Conservation (IUCN) (Rheingantz et al., 2022). On the other hand, the nerves were only studied until the elbow because other researchers had dissected the muscles of the antebrachium. This study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Universidad del Tolima (Approval number: 2.3-059).

The brachial plexus originated bilaterally from the rami ventrales of the last three cervical spinal nerves (C6, C7 and C8) and the first two thoracic spinal nerves (T1 and T2). These rami emerged between the musculi longus colli and scalenus ventralis toward the thoracic limb and adjacent regions. The rami ventrales of C6, C7 and C8 were related dorsally to the superficial cervical artery and phrenic nerve. The ramus ventralis of C8 was related dorsally to the axillary vein, while T1 was related ventrally to the axillary artery. C6 and C7 communicated ventral to the scalene muscles, while C8 and T1 only communicated when both had laterally overpassed the musculus scalenus ventralis. T2 was a small ramus that passed medially at the dorsal extreme of the second rib and joined to T1 before emerging into the axillary region (Fig. 2).

The nervus brachiocephalicus (n. brachiocephalicus) originated from a common trunk with the nervus suprascapularis from C6 (Fig. 2). It extended into the cranial skin to the shoulder between the musculi omotransversarius and cleidocephalicus and did not innervate muscles.

The nervi pectorales craniales (nn. pectorales craniales) originated from a common trunk with the nervus musculocutaneus from C6 and C7. The nervi pectorales craniales passed between the anastomosis of the external jugular and subclavian veins. It first sent a ramus communicans (communicating branch) to the nervi medianus and pectorales caudales medially to the axillary artery and distally innervated the musculi pectorales superficiales (Fig. 2,3).

The nervi pectorales caudales (nn. pectorales caudales) originated from a common trunk with the nervus thoracicus lateralis, which emerged from C8 and T1. The former sent a ramus communicans to the nn. pectorales craniales and musculocutaneus medially to the axillary artery. The nn. pectorales caudales directed together with the lateral thoracic artery toward the musculus pectoralis profundus (Fig. 2,3).

The nervus thoracicus lateralis (n. thoracicus lateralis) extended caudally with the lateral thoracic vessels medially to the musculus latissimus dorsi. It perforated this muscle to innervate the musculus cutaneus trunci (Fig. 2).

The nervus thoracicus longus (n. thoracicus longus) originated from C7 and innervated the musculi serratus ventralis thoracis and scalenus medius (Fig. 2,3).

The nervus thoracodorsalis (n. thoracodorsalis) originated from C7 and C8 on the right side, while on the left side, it originated only from C8. It only innervated the m. latissimus dorsi (Fig. 2,3).

The nervus suprascapularis (n. suprascapularis) passed between the musculi subscapularis and supraspinatus together with the suprascapular vessels, reaching the scapular notch to innervate the m. supraspinatus. It continued on the lateral side of the scapular neck to innervate the m. infraspinatus (Fig. 2,3).

Two nervi subscapulares (nn. subscapulares) originated from C6 and C7 and only innervated the musculus subscapularis (Fig. 2,3). On the right thoracic limb, the nervus subscapularis cranialis presented two rami. On the left limb, only one ramus was present, and the nervus subscapularis caudalis presented two rami.

The nervus musculocutaneus (n. musculocutaneus) originated from a common trunk with nn. pectorales craniales and extended to the brachium between the brachial artery and the musculus biceps brachii. It sent a first ramus that communicated to the n. medianus at the axillary level. Distally, it sent the ramus muscularis proximalis (proximal muscular branch) at the proximal extreme of the m. biceps brachii. In the middle third, it emitted a third ramus, which perforated the belly of the m. biceps brachii and formed nervus cutaneus antebrachii medialis. This nerve passed cranially toward the antebrachium between the m. biceps brachii and the complex formed by the musculi brachialis, pectorales and latissimus dorsi. In the distal third of the m. biceps brachii, the n. musculocutaneus emitted the ramus muscularis distalis (distal proximal branch) to innervate the m. brachialis, which passed between the m. biceps brachii and the humerus. Two other rami were formed distally, one directed to the elbow joint capsule, and another one directed to the n. medianus, which corresponds to the ramus communicans distalis (ramus communicans cum n. mediano)(Fig. 2,3).

The nervus medianus (n. medianus) was initially formed by a common trunk with the n. ulnaris from C8, T1 and T2. It received a contribution from C6 and C7 through the rami communicantes (communicating branches) formed by the nervi musculocutaneus and pectorales craniales (Fig. 3). At the distal third of the brachium, it extended together with the brachial artery to pass through the supracondylar foramen of the humerus. It received another ramus communicans from the n. musculocutaneus distal to the supracondylar foramen (Fig. 3).

The nervus ulnaris (n. ulnaris) passed between the brachial artery and brachial vein, and in the distal half of the brachium passed between the humeral shaft and the caput mediale of the m. triceps brachii. It passed deeply to the m. anconeus epitrochlearis (m. anconeus medialis) and innervated it. It continued distally deep and caudal to the medial epicondyle of the humerus to reach the antebrachium. The nervus cutaneus antebrachii caudalis (n. cutaneus antebrachii caudalis) originated directly from T1 and T2 (Fig. 3).

The nervus axillaris (n. axillaris) originated from C6 and C7 on the right limb and from C6-C8 on the left limb. It initially emitted rami to the musculi subscapularis and teres major and continued laterally passing between both muscles (Fig. 3). Laterally, it formed rami to innervate the musculi teres minor, deltoideus (pars acromialis and pars scapularis) and cleidobrachialis (Fig. 4). In the right thoracic limb, it sent a ramus to m. infraspinatus since m. teres minor was absent (Fig. 4). The nervus cutaneus brachii lateralis cranialis passed into the cranial part of the brachium between the pars acromialis of the m. deltoideus and the caput laterale of the m. triceps brachii (Fig. 4). In the right brachium, the same nerve perforated the caput laterale of the m. triceps brachii.

The nervus radialis (n. radialis) originated from C6-T2, which is directed deep to the brachial artery to emit rami musculares to the musculi tensor fasciae antebrachii and the capita mediale, accessorium and longum of the m. triceps brachii. It extended laterally between the caput longum and caput accessorium of the m. triceps brachii, where it branched to the caput laterale of the m. triceps brachii and m. anconeus. It continued distally between the m. brachialis and caput laterale of the m. triceps brachii, where it was divided into rami superficialis and profundus. The ramus superficialis is directed toward the antebrachium between the musculi brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis. The ramus profundus innervated the craniolateral antebrachial muscles and perforated the m. supinator (Fig. 5).

DISCUSSION

The origin of the brachial plexus from C6 to T2 of L. longicaudis has been found in other carnivorans, such as the mustelids Neovison vison and Meles meles (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022); the procyonids Bassariscus astutus (Davis, 1964), Potos flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), Procyon cancrivorus and Nasua nasua (Vélez García et al., 2023); and the canids Vulpes vulpes, Nyctereutes procyonoides (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022) and Canis lupus familiaris (Evans and De Lahunta, 2017; Hermanson et al., 2020; Singh, 2018). T2 had a small shape in L. longicaudis, and it contributed to the formation of the nervi medianus, ulnaris, radialis and cutaneus antebrachii caudalis, being similar to procyonids (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022; Vélez García et al., 2023), and the canid C. lupus familiaris (De Lahunta et al., 2020; Evans and De Lahunta, 2017; Hermanson et al., 2020; Singh, 2018).

The unique origin of the n. brachiocephalicus in L. longicaudis from C6 has also been reported in Martes foina (Demiraslan et al., 2015), N. vison, Martes martes (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), P. cancrivorus, N. nasua (Vélez García et al., 2023), C. lupus familiaris (Hermanson et al., 2020), Cerdocyon thous (Souza-Junior et al., 2014), Lycolopex gymnocercus (Souza-Junior et al., 2017), V. vulpes (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), Leopardus geoffroyi (Souza-Junior et al., 2018) and Puma yagouaroundi (Souza Junior et al., 2022). The absence of a ramus muscularis to m. cleidobrachialis has also been reported in procyonids (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022; Vélez García et al., 2023) and some studies in F. catus (Hudson and Hamilton, 2010; Roos and Vollmerhaus, 2005), since its primary innervation is by the axillary nerve, such as occurred in L. longicaudis.

The origin of the nn. pectorales craniales in L. longicaudis from C6-C7 has also been found in P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), P. cancrivorus, N. nasua (Vélez García et al., 2023), V. vulpes (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022; Haligur and Ozkadif, 2021), C. thous (Souza-Junior et al., 2014), L. gymnocercus (Souza-Junior et al., 2017), L. pardalis (Chagas et al., 2014), L. geoffroyi (Souza-Junior et al., 2018) and P. yagouaroundi (Souza Junior et al., 2022). The ramus communicans to the nn. pectorales caudales of L. longicaudis has been reported in procyonids and ursids as ansa pectoralis (Davis, 1964; Vélez García et al., 2023).

The origin of the nn. pectorales caudales from C8-T1 in L. longicaudis may also be in M. meles, N. procyonoides, V. vulpes (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), C. lupus familiaris (Evans and De Lahunta, 2017; Sharp et al., 1991), C. thous (Souza-Junior et al., 2014), L. gymnocercus (Souza-Junior et al., 2017), Atelocynus microtis (Pinheiro et al., 2013), Arctocephalus australis (Souza et al., 2010), F. catus (Hakkı Nur et al., 2020; Sebastiani and Fishbeck, 2005), L. geoffroyi (Souza-Junior et al., 2018), and P. yagouaroundi (Souza Junior et al., 2022). It also sends rami musculares to the m. cutaneus trunci in M. foina (Demiraslan et al., 2015) and to the m. pectoralis transversus in procyonids (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022; Vélez-García and Miglino, 2023; Vélez García et al., 2023).

The origin of the n. thoracicus lateralis from C8-T1 in L. longicaudis is also present in M. martes, N. procyonoides (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), A. australis (Souza et al., 2010), L. gymnocercus (Souza-Junior et al., 2017), C. thous (Pinheiro et al., 2014; Souza-Junior et al., 2014), C. lupus familiaris (Hermanson et al., 2020), F. catus (Nur et al., 2020; Roos and Vollmerhaus, 2005), L. geoffroyi (Souza-Junior et al., 2018) and P. yagouaroundi (Souza Junior et al., 2022). The unique innervation to m. cutaneus trunci found in L. longicaudis has also been reported in P. cancrivorus, N. nasua (Vélez García et al., 2023), A. microtis (Pinheiro et al., 2013), P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022) and M. foina (Demiraslan et al., 2015). In other species, it also innervates the m. pectoralis profundus, such as in V. vulpes, M. martes (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), C. l. familiaris (Hermanson et al., 2020), L. gymnocercus (Souza-Junior et al., 2017), C. thous (Souza-Junior et al., 2014), F. catus (Hakkı Nur et al., 2020), L. geoffroyi (Souza-Junior et al., 2018) and P. yagouaroundi (Souza Junior et al., 2022). In P. cancrivorus, N. nasua and F. catus, it also innervates the m. pectoralis abdominalis (Langworthy, 1924; Vélez-García and Miglino, 2023; Vélez‐García et al., 2023; Vélez García et al., 2023).

The origin of the n. thoracicus longus in L. longicaudis from C7 has also been present in M. meles (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), N. nasua (Vélez García et al., 2023), C. l. familiaris (Hermanson et al., 2020), L. gymnocercus (Souza-Junior et al., 2017), V. vulpes (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), C. thous (Souza-Junior et al., 2014), F. catus (Hakkı Nur et al., 2020; Roos and Vollmerhaus, 2005; Sebastiani and Fishbeck, 2005), L. geoffroyi (Souza-Junior et al., 2018), P. concolor (Barreto‐Mejía et al., 2022) and P. yagouaroundi (Souza Junior et al., 2022).

The origin of the thoracodorsal nerve from C7 and C8 of L. longicaudis has also been present in M. foina (Demiraslan et al., 2015), M. martes, M. meles (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), P. cancrivorus, N. nasua (Vélez García et al., 2023), C. l. familiaris (Hermanson et al., 2020), L. gymnocerus (Souza-Junior et al., 2017), V. vulpes (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), F. catus (Hakkı Nur et al., 2020; Roos and Vollmerhaus, 2005; Sebastiani and Fishbeck, 2005), L. geoffroyi (Souza-Junior et al., 2018), P. concolor (Barreto‐Mejía et al., 2022) and P. yagouaroundi (Souza Junior et al., 2022). The single origin from C8 in L. longicaudis may occur in C. l. familiaris (Skelding et al., 2018), C. thous (Souza-Junior et al., 2014), L. gymnocercus (Souza-Junior et al., 2017), F. catus (Hakkı Nur et al., 2020), L. pardalis (Chagas et al., 2014) and P. yagouaroundi (Souza Junior et al., 2022).

The unique origin of the n. suprascapularis from C6 in L. longicaudis has been found in M. foina (Demiraslan et al., 2015), N. nasua, P. cancrivorus (Vélez García et al., 2023), C. l. familiaris (Skelding et al., 2018), C. thous (Souza-Junior et al., 2014), L. gymnocercus (Souza-Junior et al., 2017), and Puma concolor (Barreto‐Mejía et al., 2022), Felis catus (Hakkı Nur et al., 2020; Sebastiani and Fishbeck, 2005), L. geoffroyi (Souza-Junior et al., 2018) and P. yagouaroundi (Souza Junior et al., 2022).

The origin of the nn. subscapularis in L. longicaudis from C6-C7 has also been found in M. foina (Demiraslan et al., 2015), N. vison, M. meles (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), P. cancrivorus, N. nasua (Vélez García et al., 2023), P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), C. l. familiaris (Hermanson et al., 2020; Skelding et al., 2018), V. vulpes (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022; Haligur and Ozkadif, 2021), C. thous (Pinheiro et al., 2014; Souza-Junior et al., 2014), L. gymnocercus (Souza-Junior et al., 2017), F. catus (König, 1992; Roos and Vollmerhaus, 2005; Sebastiani and Fishbeck, 2005), Leopardus pardalis (Chagas et al., 2014), L. geoffroyi (Souza-Junior et al., 2018) and P. yagouaroundi (Souza Junior et al., 2022).

The origin of the n. musculocutaneus from C6-C7 in L. longicaudis has been reported in N. vison, M. martes, M. meles (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), P. cancrivorus, N. nasua (Vélez García et al., 2023), P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), V. vulpes, N. procyonoides (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), C. thous (Pinheiro et al., 2014; Souza-Junior et al., 2014), A. microtis (Pinheiro et al., 2013), F. catus (Hakkı Nur et al., 2020; Sánchez et al., 2013), L. geoffroyi (Souza-Junior et al., 2018), L. pardalis (Chagas et al., 2014), Panthera onca (Sánchez et al., 2013), P. concolor (Barreto‐Mejía et al., 2022; Sánchez et al., 2013) and P. yagouaroundi (Souza Junior et al., 2022). The ramus communicans proximalis of n. musculocutaneus with n. medianus in L. longicaudis is similar to that described as ansa axillaris in some carnivorans (Arłamowska-Palider, 1970; Vélez García et al., 2023), which has also been described as ansa mediana in ursids (Davis, 1964) or as a communicating branch in N. nasua (Felipe et al., 2014), P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), N. vison, M. martes, and M. meles (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022). According to the International Committee on Veterinary Gross Anatomical Nomenclature (International Committee on Veterinary Gross Anatomical Nomenclature, 2017) and Backus et al. (2016), carnivorans do not present ansa axillaris. However, the ramus communicans proximalis could be an ansa axillaris due to its medial relationship with the axillary artery, such as was recently described in two procyonids (Vélez García et al., 2023). Therefore, the ansa axillaris may also be present in mustelids based on our findings in L. longicaudis and the findings of Grzeczka and Zdun (2022) in N. vison, M. martes and M. meles. On the other hand, the ramus communicans distalis at the elbow level has been reported in P. cancrivorus (Vélez García et al., 2023), P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), C. l. familiaris (Hermanson et al., 2020), C. thous (Souza-Junior et al., 2014; Vélez-García et al., 2018), L. gymnocercus (Souza-Junior et al., 2017), V. vulpes (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), A. australis (Souza et al., 2010), F. catus, P. onca, P concolor (Sánchez et al., 2013), and P. yagouaroundi (Souza Junior et al., 2022). However, rami communicans at the axillary and elbow levels, such as those in L. longicaudis, have only been reported in the procyonids P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022) and P. cancrivorus (Vélez García et al., 2023).

The origin of the n. medianus from C6-T2 of L. longicaudis was only reported in P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), P. cancrivorus and N. nasua (Vélez García et al., 2023). Passage through the supracondylar foramen with the brachial artery also occurs in F. catus (Sánchez et al., 2013), while in other species, both structures also pass with the brachial vein, such as in P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), P. onca and P. concolor (Sánchez et al., 2013). It passes alone in P. cancrivorus and N. nasua (Vélez García et al., 2023).

The origin of the n. ulnaris from C8-T2 of L. longicaudis has also been found in N. vison, M. meles (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), P. cancrivorus and N. nasua (Vélez García et al., 2023), N. procyonoides (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), and C. lupus familiaris (Evans and De Lahunta, 2017). The rami for the m. anconeus epitrochlearis in L. longicaudis has been reported in P. cancrivorus and N. nasua (Vélez García et al., 2023), P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), F. catus (Barone, 2020; König, 1992), and P. concolor (Barreto‐Mejía et al., 2022). In C. thous, when the m. anconeus epitrochlearis is present in a vestigial form, it is also innervated by the n. ulnaris (Vélez-García et al., 2018).

The origin of the n. axillaris from C6-C7 in the left thoracic limb of L. longicaudis has also been found in P. cancrivorus, N. nasua (Vélez García et al., 2023), P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), A. microtis (Pinheiro et al., 2013), C. thous (Souza-Junior et al., 2014), V. vulpes (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), F. catus (Hakkı Nur et al., 2020; Sánchez et al., 2013), L. geoffroyi (Souza-Junior et al., 2018), P. concolor (Barreto‐Mejía et al., 2022; Silva and Sánchez, 2013), P. onca (Silva and Sánchez, 2013) and P. yagouaroundi (Souza Junior et al., 2022). The C6-C8 origin in the left thoracic limb of L. longicaudis has been found in P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), M. martes, N. procyonoides (Grzeczka and Zdun, 2022), C. thous (Souza-Junior et al., 2014), and L. gymnocercus (Souza-Junior et al., 2017). The innervation to the m. cleidobrachialis is similar to that of other carnivorans, such as P. cancrivorus, N. nasua (Vélez García et al., 2023), P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), A. microtis (Pinheiro et al., 2013), F. catus (König, 1992; Liebich et al., 2020; Roos and Vollmerhaus, 2005; Sebastiani and Fishbeck, 2005; Vélez‐García et al., 2023) and P. concolor (Barreto‐Mejía et al., 2022).The innervation to the m. infraspinatus in the right thoracic limb of L. longicaudis allows us to suggest that this innervation is due to fusion with the m. teres minor during embryonic development. In other otters (subfamily Lutrinae), it is normal to find this muscle fused to the m. infraspinatus (Howard, 1973; Macalister, 1873).

The origin of the n. radialis in L. longicaudis from C6-T2 has only been described in P. cancrivorus (Vélez García et al., 2023), P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022), and C. l. familiaris (Sharp et al., 1991). Its ramus superficialis extends cranially and distally between the brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis muscles in F. catus due to the proximal origin of the m. brachioradialis (Sánchez et al., 2013), such as occurs in L. longicaudis.

The n. cutaneus antebrachii caudalis originated directly from T1-T2 in L. longicaudis, which also occurs in P. cancrivorus, N. nasua (Vélez García et al., 2023), and P. flavus (Enciso-García and Vélez-García, 2022). In other species, it is a ramus derived from the ulnar nerve, such as in C. l. familiaris (Hermanson et al., 2020; International Committee on Veterinary Gross Anatomical Nomenclature, 2017; Singh, 2018), L. gymnocercus (Souza-Junior et al., 2017) and F. catus (Hakkı Nur et al., 2020; International Committee on Veterinary Gross Anatomical Nomenclature, 2017). However, this nerve may originate independently only from T1 in F. catus (König, 1992; Roos and Vollmerhaus, 2005).

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, although the present study was limited to one specimen of L. longicaudis, some interesting differences that are not frequent in other carnivorans were found, such as the origin from T2; two rami communicantes from the n. musculocutaneus to the n. medianus; absence of a ramus to the m. coracobrachialis due to the absence of said muscle; m. cleidobrachialis only innervated by the n. axillaris; m. infraspinatus innervated by the n. axillaris due to a fusion with the m. teres minor; and the n. cutaneus antebrachii caudalis independent of the n. ulnaris. Thus, these differences should be considered in veterinary procedures on the thoracic limb of L. longicaudis, such as locoregional anesthesia, neurological diagnosis, and surgeries. However, further studies should be performed with more specimens to define the common pattern of the brachial plexus in this species and review which would be the anatomical variations to be considered in clinical practice (Vélez-García et al., 2018; Żytkowski et al., 2021).

Acknowledgments - Thanks to Universidad del Tolima (Colombia) for financially supporting this research, and to CORTOLIMA for donating the specimen.

Funding support - This research was funded by the Research and Scientific Development Office (Oficina de investigaciones y desarrollo científico) of the Universidad del Tolima (research project number 160130517).

Conflict of Interest Statement - The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions - JFVG, KJRA and OLAP performed the conception and design of the study. JFVG, KJRA and SDP acquired and interpreted the data. All authors drafted the article and approved the last version.

REFERENCES

Ansón, A., Gil, F., Laredo, F. G., Soler, M., Belda, E., Ayala, M.D., Agut, A. (2013). Correlative ultrasound anatomy of the feline brachial plexus and major nerves of the thoracic limb. Veterinary Radiology and Ultrasound, 54 (2): 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/vru.12012

Arłamowska-Palider, A. (1970). Comparative anatomical studies of nervus musculocutaneus in mammals. Acta Theriologica, 15 (22): 343–356. https://rcin.org.pl/ibs/Content/11381/PDF/BI002_2613_Cz-40-2_Acta-T15-nr22-343-356_o.pdf

Backus, T. C., Solounias, N., Mihlbachler, M. C. (2016). The Brachial Plexus of the Sumatran Rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) and Application of Brachial Plexus Anatomy Toward Mammal Phylogeny. Journal of Mammalian Evolution, 23 (1): 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10914-015-9297-6

Barone, R. (2020). Anatomie comparée des mammifères Domestiques. Tome 2: Arthrologie et Myologie. (4th ed.). Association Centrale D’Entraide Vétérinaire, Paris. ISBN: 9782957196012

Barreto‐Mejía, R., Ceballos, C.P., Tamayo‐Arango, L. J. (2022). Anatomical description of the origin and distribution of the brachial plexus to the antebrachium in one puma ( Puma concolor ) (Linnaeus, 1771). Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia, 51 (1): 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/ahe.12761

Chagas, K.L.S., Moura Fé, L.C., Pereira, L. C., Lima, A.R., Branco, É. (2014). Descrição morfológica do plexo braquial de jaguatirica (Leopardus pardalis). Biotemas, 27 (2): 171-176. . https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-7925.2014v27n2p171

Davis, D.D. (1964). The giant panda: a morphological study of evolutionary mechanisms. Fieldiana, 3: 1–339. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/4236372

De Lahunta, A., Glass, E., Kent, M. (2020). de Lahunta’s Veterinary Neuroanatomy and Clinical Neurology. Saunders elsevier, Missouri.

Demiraslan, Y., Aykut, M., Özgel, Ö. (2015). Macroanatomical characteristics of plexus brachialis and its branches in martens (Martes foina). Turkish Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, 39: 693–698. https://doi.org/10.3906/vet-1506-48

Emmons, L., Feer, F. (1997). Neotropical Rainforest Mammals: a Field Guide (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press, Chicago. ISBN: 0-226-20719-6

Enciso-García, L.M., Vélez-García, J.F. (2022). Origin and distribution of the brachial plexus in kinkajou ( Potos flavus – Schreber, 1774). Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia, 51 (2): 221–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/ahe.12781

Evans, H. E., De Lahunta, A. (2017). Guide to the dissection of the dog (8th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences, St. Louis, Missouri. ISBN: 9780323391658

Felipe, R., Silva, F., França, G.L., Silva, E. M., Leonel, L.C., Carvalho-Barros, R.A., … Silva, Z. (2014). Anatomia descritiva do nervo musculocutâneo em quatis (Nasua nasua, Linnaeus, 1766). Enciclopédia Biosfera, 10 (19): 92–98. https://conhecer.org.br/ojs/index.php/biosfera/article/view/2528

Gallo-Reynoso, J. P., Macías-Sánchez, S., Arellano-Nicolás, E., González-Romero, A. (2013). Longitud, masa corporal, y crecimiento de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en México. Therya, 4 (2): 219–230. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-13-132

González-Christen, A., Delfín-Alfonso, C.A., Sosa-Martínez, A. (2013). Distribución y abundancia de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897), en el Lago de Catemaco Veracruz, México. Therya, 4 (2): 201–217. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-13-125

Grzeczka, A., Zdun, M. (2022). The structure of the brachial plexus in selected representatives of the Caniformia suborder. Animals, 12 (5): 566.https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12050566

Hakkı Nur, İ., Keleş, H., Pérez, W. (2020). Origin and distribution of the brachial plexus of the Van cats. Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia, 49 (2): 251–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/ahe.12523

Haligur, A., Ozkadif, S. (2021). Macroanatomical investigation of the plexus brachialis in the red fox (Vulpes vulpes). Pakistan Journal of Zoology, 53 (5): 1617–1622. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.pjz/20180815090812

Hermanson, J. W., Evans, H., De Lahunta, A. (2020). Miller and Evan’s Anatomy of the Dog (5th ed.). Elsevier Inc, St. Louis, Missouri. ISBN: 9780323546010

Howard, L. D. (1973). Muscular anatomy of the fore-limb of the sea otter (Enhydra lutris). Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, 39: 415-416. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/15774583

Hudson, L. C., Hamilton, W. C. (2010). Atlas of feline anatomy for veterinarians (2nd ed.). Jackson: Teton NewMedia. ISBN: 1-59161-044-3

International Committee on Veterinary Gross Anatomical Nomenclature. (2017). Nomina Anatómica veterinaria (6th ed.; World Association of Veterinary Anatomists, Ed.). World Association of Veterinary Anatomists, Hannover. ISBN: 2-7114-8194-8

König, H. E. (1992). Anatomie der Katze: Mit Hinweisen für die tierärztliche Praxis. Gustav Fischer. ISBN: 9783437204920

Langworthy, O.R. (1924). The Panniculus carnosus in Cat and Dog and Its Genetical Relation to the Pectoral Musculature. Journal of Mammalogy, 5 (1): 49. https://doi.org/10.2307/1373485

Liebich, H.G., Maierl, J., König, H.E. (2020). Forelimbs or thoracic limbs (membra thoracica). In: König, H.E., Liebich, H.G., (Eds.), Veterinary anatomy of domestic animals. Textbook and colour atlas (7th ed.). Georg Thieme Verlag, Stuttgart, Germany, pp. 171–242. ISBN: 9783132429345

Macalister, A. (1873). On the Anatomy of Aonyx. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Science, 1: 539–547. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20540967

Mayor-Victoria, R., Botero-Botero, A. (2010). Dieta de la nutria neotropical Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora, Mustelidae) en el río Roble, Alto Cauca, Colombia. Acta Biológica Colombiana, 15: 237–244. https://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0120-548X2010000100016

Mencalha, R., Fernandes, N., Sousa, C. A. dos S., Abidu-Figueiredo, M. (2014). A cadaveric study to determine the minimum volume of methylene blue to completely color the nerves of brachial plexus in cats. An update in forelimb and shoulder surgeries. Acta Cirurgica Brasileira, 29 (6): 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-86502014000600006

Mosquera-Guerra, F., Velandia-Barragán, C., Rojas, J. E., Ospina-Posada, V., Caicedo-Herrera, D., Cortés-Ladino, A.M., and Trujillo, F. (2018). La nutria neotropical, una especie en peligro de extinción. Bogotá. ISBN: 978-958-5480-08-7

Nivelo-Villavicencio, C., Sánchez-Karste, F., Espinoza, N., Siddons, D., Córdova, J. (2020). La nutria neotropical Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora, Mustelidae) en los Andes al sur de Ecuador. Notas Sobre Mamíferos Sudamericanos, 2 (1): 2–6. https://doi.org/10.31687/saremNMS.20.0.12

Nyakatura, K., Bininda-Emonds, O.R. (2012). Updating the evolutionary history of Carnivora (Mammalia): a new species-level supertree complete with divergence time estimates. BMC Biology, 10 (1): 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7007-10-12

Pinheiro, L.L., Branco, É.R., De Souza, D.C., De Souza, A.C.B., Pereira, L.C., and Lima, A.R. De. (2013). Descrição do plexo braquial do cachorro-do-mato-de-orelhas-curtas (Atelocynus microtis - Sclater, 1882): relato de caso. Biotemas, 26 (3): 203–209. https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-7925.2013v26n3p203

Pinheiro, L.L., Branco, É., Souza, D.C., Pereira, L.H.C., Lima, A.R. (2014). Descrição do plexo braquial do cachorro-do-mato (Cerdocyon thous Linnaeus, 1766). Ciência Animal Brasileira, 15 (2): 213–219. https://doi.org/10.5007/2175-7925.2013v26n3p203

Restrepo, C. ., Botero-Botero, Á., Puerta-Parra, J., Franco-Pérez, L., Guevara, G. (2018). El caso de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis Olfers, 1818) como mascota en el río Magdalena (Colombia). Boletín Científico. Centro de Museos. Museo de Historia Natural, 22 (2): 76–83. https://doi.org/10.17151/bccm.2018.22.2.6

Rheingantz, M.L., Rosas-Ribeiro, P., Gallo-Reynoso, J., Fonseca da Silva, V. C., Wallace, R., Utreras, V., and Hernández-Romero, P. (2022). Lontra longicaudis (amended version of 2021 assessment). https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T12304A219373698.en

Rheingantz, M.L., Santiago-Plata, V. M., Trinca, C.S. (2017). The Neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis : a comprehensive update on the current knowledge and conservation status of this semiaquatic carnivore. Mammal Review, 47 (4): 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/mam.12098

Roos, H., Vollmerhaus, B. (2005). Konstruktionsprinzipien an der Vorder- und Hinterpfote der Hauskatze (Felis catus). 4. Mitteilung: Muskelinnervation und Bewegungsanalyse+. Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia: Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series C, 34 (1): 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0264.2004.00562.x

Sánchez, H.L., Silva, L.B., Rafasquino, M.E., Mateo, A.G., Zuccolilli, G.O., Portiansky, E.L., Alonso, C.R. (2013). Anatomical study of the forearm and hand nerves of the domestic cat (Felis catus), puma (Puma concolor) and jaguar (Panthera onca). Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series C: Anatomia Histologia Embryologia, 42 (2): 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0264.2012.01170.x

Sebastiani, M., Fishbeck, D.W. (2005). Mammalian anatomy: The Cat (2nd ed.). Morton Publishing Company, Englewood. ISBN: 9780895826831

Sharp, J. W., Bailey, C. S., Johnson, R. D., Kitchell, R. L. (1991). Spinal root origin of the radial nerve and nerves innervating shoulder muscles of the dog. Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia: Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series C, 20 (3): 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0264.1991.tb00297.x

Silva, L. B., Sánchez, H.L. (2013). La inervación del miembro torácico en felinos. AnAlectA Vet, 33 (1): 10–17.

Singh, B. (2018). Dyce, Sack and Wensing’ textbook of veterinary anatomy. (5th ed.). Elsevier, Missouri. ISBN: 978-0323442640

Skelding, A., Valverde, A., Sinclair, M., Thomason, J., Moens, N. (2018). Anatomical characterization of the brachial plexus in dog cadavers and comparison of three blind techniques for blockade. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 45 (2): 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaa.2017.11.002

Souza, D.A.S. de, Castro, T.F. de, Franceschi, R.D.C., Silva Filho, R.P., Pereira, M.A.M. (2010). Formação do plexo braquial e sistematização dos territórios nervosos em membros torácicos de lobos-marinhos Arctocephalus australis. Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Research and Animal Science, 47(2), 168–174. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1678-4456.bjvras.2010.26842

Souza-Junior, P., Carvalho, N. da C., Medeiros‐do‐Nascimento, R., Dantas, P. de O., Bernardes, F.C.S., Abidu‐Figueiredo, M. (2022). Brachial plexus formation in Jaguarundi (Puma yagouaroundi). Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia, 51 (6): 746-755 https://doi.org/10.1111/ahe.12853

Souza-Junior, P., Carvalho, N.C., Mattos, K., Santos, A.L.Q. (2014). Origens e ramificações do plexo braquial no cachorro-do-mato Cerdocyon thous (Linnaeus, 1766). Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira, 34 (10): 1011–1023. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-736X2014001000015

Souza-Junior, P., da Cruz de Carvalho, N., de Mattos, K., Abidu Figueiredo, M., Luiz Quagliatto Santos, A. (2017). Brachial Plexus in the Pampas Fox (Lycalopex gymnocercus): a Descriptive and Comparative Analysis. The Anatomical Record, 300 (3): 537–548. https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.23509

Souza-Junior, P., Wronski, J. G., Carvalho, N. C., Abidu-Figueiredo, M. (2018). Brachial plexus in the Leopardus geoffroyi. Ciência Animal Brasileira, 19: 1-14 e – 50805 https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-6891v19e-51240

Trujillo, F., Mosquera-Guerra, F. (2018). Nutrias de la Orinoquia colombiana. Bogotá: Cepsa y Fundación Omacha. ISBN: 978-958-8554-67-9.

Vélez García, J.F., de Carvalho Barros, R.A., Miglino, M.A. (2023). Origin and distribution of the brachial plexus in two procyonids (Procyon cancrivorus and Nasua nasua, Carnivora). Animals, 13 (2): 210. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13020210

Vélez-García, J. F., Patiño-Holguín, C., Duque-Parra, J. E. (2018). Anatomical variations of the caudomedial antebrachial muscles in the crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous). International Journal of Morphology, 36 (4): 1193–1196. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95022018000401193

Vélez‐García, J.F., Kfoury Junior, J.R., Miglino, M.A. (2023). Evolutionary study of the extrinsic thoracic limb muscles of the domestic cat (Felis catus, Feliformia, Carnivora) based on their topology and innervation. Acta Zoologica. https://doi.org/10.1111/azo.12479

Vélez-García, J.F., Miglino, M.A. (2023). Evolutionary comparative analysis of the extrinsic thoracic limb muscles in three procyonids (Procyon cancrivorus Cuvier, 1798, Nasua nasua Linnaeus, 1766, and Potos flavus Schreber, 1774) based on their attachments and innervation. Anatomical Science International, 98 (2): 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12565-022-00696-1

Żytkowski, A., Tubbs, R. S., Iwanaga, J., Clarke, E., Polguj, M., Wysiadecki, G. (2021). Anatomical normality and variability: Historical perspective and methodological considerations. Translational Research in Anatomy, 23: 100105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tria.2020.100105

Résumé: Premier Rapport sur l’Origine et la Distribution du Plexus Brachial dans les Régions Scapulaires et Brachiales d’une Loutre à Longue Queue (Lontra longicaudis)

Cet article rapporte un cas de mortalité inhabituel et accidentel de loutres cendrées (Aonyx cinereus), piLa loutre à longue queue (Lontra longicaudis) est une espèce carnivore appartenant à la famille des Mustelidae. Il n’existe aucun rapport sur le plexus brachial et sa connaissance est essentielle au diagnostic clinique et pour les interventions chirurgicales de la cage thoracique. Des variations dans l’origine et la répartition du plexus brachial peuvent exister selon les espèces de carnivores. Ainsi, la présente étude visait à décrire l’origine du plexus brachial et la répartition de ses nerfs dans les régions scapulaire et brachiale de L. longicaudis. Un spécimen de L. longicaudis fixé au formaldéhyde a été disséqué. Le plexus brachial provient des trois derniers nerfs spinaux cervicaux et des deux premiers nerfs spinaux thoraciques (C6-T2). Les nerfs du plexus brachial et leur répartition dans les régions scapulaire et brachiale de L. longicaudis étaient similaires à ceux décrits chez la plupart des carnivores. Cependant, des différences ont été trouvées, notamment deux branches communicantes (rami communicantes) du nerf musculo-cutané au nerf médian, une proximale et une distale. Le ramus communicans proximalis a également été trouvé chez d’autres mustélidés, tandis que le ramus communicans distalis n’a pas été trouvé chez d’autres mustélidés. Ainsi, le plexus brachial de L. longicaudis peut présenter des variations par rapport à celui des autres carnivores.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Primer Reporte del Origen y Distribución del Plexo Braquial en las Regiones Escapular y Braquial en una Nutria de Río Neotropical (Lontra longicaudis)

La nutria de río neotropical (Lontra longicaudis) es una especie del orden Carnívora perteneciente a la familia Mustelidae. No hay reportes sobre su plexo braquial, siendo su conocimiento necesario para el diagnóstico clínico y procedimientos quirúrgicos en el miembro torácico. Pueden existir variaciones en el origen y distribución del plexo braquial entre distintas especies de carnívoros. Por lo tanto, el objetivo del presente estudio es describir el origen del plexo braquial y la distribución de sus nervios en las regiones escapular y braquial de L. longicaudis. Fue diseccionado un espécimen fijado en formaldehído. El plexo braquial se originó de las últimos tres nervios espinales cervicales y los primeros dos nervios espinales torácicos (C6-T2). Los nervios del plexo braquial y su distribución en las regiones escapular y braquial en L. longicaudis fueron similares a los encontrados en la mayoría de carnívoros. Sin embargo, fueron encontradas algunas diferencias, tales como dos ramos comunicantes (rami communicantes) del nervio musculocutáneo con el nervio mediano, uno proximal y uno distal. El ramo comunicante proximal ha sido encontrado en otros mustélidos, mientras el ramo comunicante distal no ha sido encontrado en otros mustélidos. En conclusión, el plexo braquial de L. longicaudis puede presentar variaciones comparativamente con otros carnívoros.

Vuelva a la tapa