IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Volume 41 Issue 4 (November 2024)

Citation: Elves-Powell, J., Kim, J.H., Axmacher, J.C., and Durant, S.M. (2024). The Trade in Eurasian Otter, Lutra lutra, in North Korea. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 41 (4): 210 - 216

The Trade in Eurasian Otter, Lutra lutra, in North Korea.

Joshua Elves-Powell1,2*, Jee Hyun Kim3, Jan C. Axmacher2,4 ,and Sarah M. Durant1

1Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, London, UK

2Department of Geography, University College London, London, UK

3College of Veterinary Medicine, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

4Faculty of Environmental and Forest Sciences, Agricultural University of Iceland, Keldnaholt, Iceland

*Corresponding Author Email: joshua.powell@zsl.org

Received 29th February 2024, accepted 24th April 2024

Abstract: Exploitation for the purpose of trade is considered an important threat to all Asian otter species. To date, there has been limited information available regarding the use and trade of Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, or North Korea). This study provides the first assessment of otter trade in North Korea. Surveys with North Korean defectors revealed that despite hunting of the species having been banned in North Korea since 1959 and the species being listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), Eurasian otters are opportunistically taken by North Korean hunters for illegal wildlife trade with buyers in the People’s Republic of China (China). Otter skins are reported to command a high price, compared to those of other furbearers, in black market trade. Eurasian otters are also reported to be farmed for their fur by the North Korean state for international trade to China, and potentially for domestic use. We caution that reported trade may breach China’s CITES commitments and should be addressed as a matter of priority.

Keywords: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), Wildlife farming, Illegal wildlife trade, Skin trade, China, Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

INTRODUCTION

The Korean Peninsula is part of the native range of the Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra). The Eurasian otter is listed as Near Threatened by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (Loy et al., 2022), and has been classified as an endangered species in the Republic of Korea (ROK, or South Korea) since 1998 (Jo et al., 2018). In the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, or North Korea), the hunting of Eurasian otters has officially been banned since 1959, with the species protected as a Natural Monument - a protected status granted to certain Korean natural resources, including some wild animals and plants (Jo et al., 2018). The Eurasian otter is also listed on Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which prohibits all commercial trade in the species by Parties to the convention.

One of the main threats to otter populations in Asia is thought to be harvesting of animals for the purpose of trade (Duckworth and Hills, 2008; Shepherd and Nijman, 2014; Duplaix and Savage, 2018; Gomez et al., 2019), either as live animals for the pet trade (Siriwat and Nijman, 2018), skins for clothing, meat for human food, or body parts for traditional medicine (Gomez and Shepherd, 2019). Despite its protected status, the Eurasian otter is one of the species which continue to be traded illegally (Gomez et al., 2016).

Basnet et al. (2020) highlight the need for further investigation, monitoring and reporting of illegal trade and demand for otters, including the sources of traded animals. However, in their assessment of research effort pertaining to otters in Asia, they recorded no scientific publications on any aspect of the ecology, management, or conservation of otters in North Korea; in contrast, South Korea recorded the second highest number of such studies in Asia (Basnet et al., 2020).

Historical records from Joseon dynasty Korea (1392-1897) (Powell et al., 2021) show that the provision of high-quality otter fur was one of the valuable commodities historically submitted as tributary trade to China (see, for example, Sejongsilok, 1428a; Sejongsilok, 1428b; Sejongsilok, 1429; Munjongsilok, 1451; Sejosilok 1460), with the species sometimes recorded alongside skins of tiger (Panthera tigris) and leopard (P. pardus) (Injosilok, 1639). By the mid-15th century, growing demand for otter fur among the Korean ruling classes led to the acquisition of otter skins both from domestic hunting and trade with the Jurchen tribes along Korea’s northern border (Kim, 2011). However, not all skin trade was conducted through official channels. With the opening of trade routes with Qing dynasty China (1636–1912), Korean merchants purchased large quantities of otter skins from local hunters and then exported them to China (Yoo, 1997).

Continued harvesting for trade into the 20th century is known to have put further pressure on Korean otter populations (Jo et al., 2018). In South Korea, where otter fur had been regarded as an expensive material in the production of clothing (Jo et al., 2018), the Eurasian otter received protection through designation as Natural Monument No. 330 in 1982 and as a first-class endangered species in 1998, with prohibitions on capturing or taking from the wild. There is no longer considered to be any substantial demand for otter skins in South Korea (Jo et al., 2018). The Eurasian otter was also designated as a Natural Monument in North Korea and the 16th February 1959 Presidential Decree About protecting and multiplying useful animals and plants banned hunting of the species. However, information on implementation is scarce.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In order to investigate wildlife trade in Eurasian otter alongside other carnivorans in North Korea, we interviewed 42 North Korean defectors in the UK and South Korea in 2021-2022. All participants were over the age of 18 and were former North Korean residents, but otherwise had a range of individual backgrounds and experiences, including as hunters, wildlife trade middlemen and buyers, veterinarians, and soldiers. Informed written consent was obtained following explanation of the nature of the study and research methodology (for further details, see, Elves-Powell et al.,2024). Interviews used a series of open-ended questions, pertaining to use and trade of wildlife (not specifically focal species). All interviews and the data collected were anonymous and recorded at a province level only, in order to protect the identity of participants and any family members still in North Korea.

RESULTS

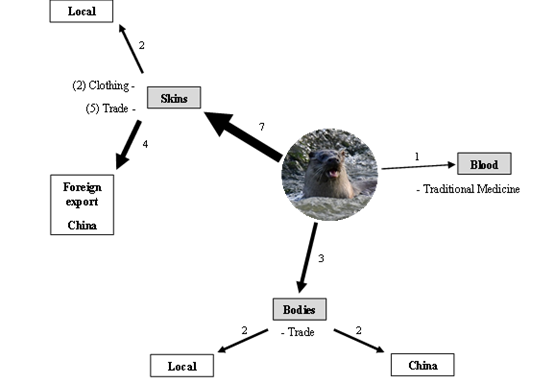

Despite the Eurasian otter’s protection under North Korean law, trade in Eurasian otter was reported by 9 participants in our study (21.4% of participants), including individuals with firsthand experience of illegal wildlife trade in North Korea, either as hunters or middlemen. Trade in otter skins, bodies and blood was reported (Fig. 1), with the People’s Republic of China (China) identified as an important destination. The most recent report was from 2018, a case of attempted trade with China, and we suspect that trade is likely ongoing.

Eurasian otter was reportedly highly valued, with three participants who were familiar with black-market wildlife trade in North Korea noting that the species was more valuable than Siberian weasel (Mustela sibirica), a reported staple of North Korean skin trade. Indeed, the only other important furbearers considered to be more valuable were martens (Martes spp.). Participants reported that due to the high prices commanded by otter skins, they were used for international trade. Three different processes were identified by which otter skins and bodies would enter trade. In the first, hunters who captured otters in the wild would prepare skins and submit them to the North Korean state. It was not specifically stated who would be the recipient of these skins, but participants reported that government agencies involved in skin trade exist in North Korea. Alternatively, a wild animal would be captured alive, transported to an otter farm and reared, with otters then being subsequently traded to China. It was difficult to obtain information on otter farms in North Korea, which may be explained by the suggestion from one participant that the North Korean military was involved in their management. For example, it is not clear whether otters were actually bred at these sites, or whether wild-harvested animals were simply housed and reared there, a common concern regarding wildlife farms holding small carnivores (Elves-Powell et al., 2023). Finally, a hunter who had harvested an otter and wanted to privately sell it to China, could either directly sell the whole animal to cross-border smugglers, or ask a North Korean middleman to find a buyer. The porosity of the North Korea-China border to wildlife trade is illustrated by the observation that in one such case, the otter was returned to North Korea, because the buyer in China wanted a live animal rather than a body.

Domestic use of otter skins for clothing (for example, otter fur mufflers) was reported to have been popular in the past, but to have since declined. It was noted that relatively few households in North Korea would now have access to otter-derived products (the North Korean economy collapsed in the 1990s, resulting in severe economic hardship for the majority of the country’s citizens) and these would be available only to those who personally knew hunters. Participants contrasted this to otter skins and bodies being widely sold to China.

DISCUSSION

The reported persistence of North Korean trade in Eurasian otter into the 21st century raises several important concerns. Legal protections for otters in North Korea are clearly not being implemented effectively, and all three identified processes by which otter body parts enter trade chains in North Korea likely involve some illegal activity. Black market trade in otter skins is, by its nature, unregulated and therefore potentially vulnerable to unsustainable harvesting practices. Perhaps of even greater concern is the North Korean state’s apparent participation in Eurasian otter trade. Reported trade to China would be illegal under international law, as it concerns commercial, international trade in a CITES Appendix I species, which China is a Party to. The reported submission of otter skins by North Korean hunters to the North Korean state, and the suspected stocking of state-owned otter farms with wild animals, strongly suggests that official prohibition of the taking of wild Eurasian otters in North Korea is ignored by the state itself.

It is difficult to assess the impact of this trade, because there is little reliable information on Eurasian otter populations in North Korea (Jo et al., 2018). Similarly, quantifying volumes of trade is almost impossible. Even in contexts where government data on illegal trade is available, which is not the case for North Korea, gauging how this relates to actual levels of trade presents a substantial challenge (see, for example, Gomez et al., 2016). However, one participant in our study provided an assessment of changes they had observed: they reported that they saw Eurasian otters throughout their time in North Korea, up until when they left the country in 2014, but that the frequency of observation had decreased over time. The participant was of the belief that the otter population had declined because of harvesting and trade in otter skins, which they specifically linked to high demand from China.

Demand for otter skins and other body parts in China has been highlighted by previous studies (Lau et al., 2010; Gomez et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018) and Eurasian otter populations in the country’s northeast are known to have declined heavily (Zhang et al., 2016), including in Changbaishan Nature Reserve, which borders North Korea (Piao et al., 2011). Otter skins linked to cross-border smuggling - originating from, or transiting through, India, Nepal, Bhutan or Myanmar (Burma) - have previously been seized by law enforcement authorities in China, including in consignments with Asian big cat skins (Gomez et al., 2016). However, we are not aware of any seizures having been made in China of otters, otter body parts, or derived products linked to North Korea, and no such records could be found on the TRAFFIC Wildlife Trade Portal (https://www.wildlifetradeportal.org/ ), Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) Global Environmental Crime Tracker (https://eia-international.org/gect ), or CITES Trade Database (https://trade.cites.org/ ).

We urge the North Korean state to cease involvement in the trade of otters and the stocking of otter farms with wild animals. We appeal to China to address the illegal import of Eurasian otter skins from North Korea and so fulfil its CITES commitments. Finally, we recommend that reserachers and conservationists seeking to engage with otter conservation in North Korea at the current time do so with caution and conscious of important obstacles to collaboration, ongoing international sanctions, and Pyongyang’s apparent willingness to engage in a wide variety of illicit trades to generate income (Kirby et al., 2014; Wang and Blancke, 2015).

Acknowledgements - The authors thank Jong In Choi for the image of a Eurasian otter used in Figure 1. Joshua Elves-Powell was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council [grant number NE/S007229/1]. This research was supported by Research England. Ethical approval for this study was received from the UCL Research Ethics Committee (UCL Ethics Project ID Number: 18841/001).

REFERENCES

Basnet, A., Ghimire, P., Timilsina, Y.P., Bist, B.S. (2020). Otter research in Asia: Trends, biases and future directions. Global Ecology and Conservation, 24: e01391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01391

de Silva, P.K. (2011). Status of Otter Species in the Asian Region Status for 2007. Proceedings of Xth International Otter Colloquium. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin, 28(A): 97-107. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume28A/de_Silva_2011.html

Duckworth, J.W., Hills, D.M. (2008). A specimen of hairy-nosed otter Lutra sumatrana from far Northern Myanmar. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin, 25(1): 60-67. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume25/Duckworth_Hills_2008.html

Duplaix, N., Savage, M. (2018). The Global Otter Conservation Strategy. IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group, Salem, Oregon, USA. https://www.otterspecialistgroup.org/osg-newsite/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/IUCN-Otter-Report-DEC%2012%20final_small.pdf

Elves-Powell, J., Dolan, J., Durant, S.M., Lee, H., Linnell, J.D.C., Turvey, S.T., Axmacher, J.C. (2024). Integrating local ecological knowledge and remote sensing reveals patterns and drivers of forest cover change: North Korea as a case study. Regional Environmental Change, 24: 97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-024-02254-z

Elves-Powell, J., Neo, X., Park, S., Woodroffe, R., Lee, H., Axmacher, J.C., Durant, S.M. (2023). A preliminary assessment of the wildlife trade in badgers (Meles leucurus and Arctonyx spp.) (Carnivora: Mustelidae) in South Korea. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity, 16(2): 204-214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japb.2023.03.004

Gomez, L., Leupen, B.T.C., Theng, M., Fernandez, K., Savage, M. (2016). Illegal otter trade: an analysis of seizures in selected Asian countries (1980-2015). TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia. https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/2402/illegal-otter-trade-asia.pdf

Gomez, L., Shepherd, C.R. (2019). Stronger International Regulations and Increased Enforcement Effort is needed to end the Illegal Trade in Otters in Asia. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin, 36(2): 71-76. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume36/Gomez_Shepherd_2019.html

Gomez, L., Shepherd, C.R., Morgan, J. (2019). Improved Legislation and Stronger Enforcement Actions needed as the Online Otter Trade in Indonesia continues. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin, 36(2): 64-70. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume36/Gomez_et_al_2019.html

Injosilok. (1639). The Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty (1639, September 12). Seoul. Available online at: https://sillok.history.go.kr

Jo, Y., Baccus, J.T., Koproswki, J. (2018). Mammals of Korea. National Institute of Biological Resources, Incheon, Republic of Korea. ISBN: 978-89-6811-369-7

Kim, S.N. (2011). The Development of the Fur Trade between Joseon and Jurchens during the 16th Century. Journal of Northeast Asian History, 152: 71-108.

Kirby, M.D., Darusman, M., Biserko, S. (2014). Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. United Nations Human Rights Council, Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/hrc/co-idprk/reportofthe-commissionof-inquiry-dprk

Lau, M.W-N., Fellowes, J.R., Chan, B.P.L. (2010). Carnivores (Mammalia: Carnivora) in South China: status review with notes on the commercial trade. Mammal Review, 40(4): 247-292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2907.2010.00163.x

Loy, A., Kranz, A., Oleynikov, A., Roos, A., Savage, M., Duplaix, N. (2022). Lutra lutra (amended version of 2021 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: e.T12419A218069689. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T12419A218069689.en

Munjongsilok. (1451). The Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty (1451, January 10). Seoul. Available online at: https://sillok.history.go.kr

Piao, Z.J., Sui, Y.Z., Wang, Q., Li, Z., Zhu, L.J. (2011). Population fluctuation and resources protection of otter in Changbai Mountain Nature Reserve. Journal of Hydroecology, 32: 115–120.

Powell, J., Axmacher, J.C., Linnell, J.D.C., Durant, S.M. (2021). Diverse Locations and a Long History: Historical Context for Urban Leopards (Panthera pardus) in the Early Anthropocene From Seoul, Korea. Frontiers in Conservation Science, 2: 765911. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2021.765911

Sejongsilok. (1428a). The Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty (1428, August 6). Seoul. Available online at: https://sillok.history.go.kr (accessed January 12, 2024).

Sejongsilok. (1428b). The Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty (1428, August 10). Seoul. Available online at: https://sillok.history.go.kr (accessed January 12, 2024).

Sejongsilok. (1429). The Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty (1429, November 12). Seoul. Available online at: https://sillok.history.go.kr (accessed January 12, 2024).

Sejosilok. (1460). The Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty (1460, March 8). Seoul. Available online at: https://sillok.history.go.kr (accessed January 19, 2024).

Shepherd, C.R., Nijman, V. (2014). Otters in the Mong La Wildlife Market, with a First Record of Hairy-nosed Otter Lutra sumatrana in Trade in Myanmar. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin, 31(1): 31-34. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume31/Shepherd_Nijman_2014.html

Siriwat, P., Nijman, V. (2018). Illegal pet trade on social media as an emerging impediment to the conservation of Asian otters species. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity, 11(4): 469-475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japb.2018.09.004

Wang, P., Blancke, S. (2015). Mafia State: The Evolving Threat of North Korean Narcotics Trafficking. The RUSI Journal, 159(5): 52-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2014.969944

Yoo, S.J. (1997). The Development of a Commodity Economy. In: National Institute of Korean History (Ed.). Korean History 33. Tamgudang, Seoul, Republic of Korea, pp. 438-460.

Zhang, L., Wang, Q., Yang, L., Li, F., Chan, B.P.L., Xiao, Z., Li, S., Song, D., Piao, Z., Fan, P. (2018). The neglected otters in China: Distribution change in the past 400 years and current conservation status. Biological Conservation, 228: 259-267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.10.028

Zhang, R., Yang, L., Laguardia, A., Jiang, Z., Huang, M.J., Lv, J. Ren, Y., Zhang, W., Luan, X. (2016). Historical distribution of the otter (Lutra lutra) in north-east China according to historical records (1950–2014). Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 26: 602–606. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2624

Résumé: Le Commerce de la Loutre d’Eurasienne Lutra lutra en Corée du Nord

L’exploitation à des fins commerciales est considérée comme une menace importante pour toutes les espèces de loutres d’Asie. À ce jour, les informations disponibles concernant l’utilisation et le commerce de la loutre eurasienne (Lutra lutra) en République Populaire Démocratique de Corée (RPDC ou Corée du Nord) sont peu nombreuses. Cette étude fournit la première évaluation du commerce de la loutre eurasienne en Corée du Nord. Des enquêtes auprès de déserteurs nord-coréens ont révélé que, bien que la chasse de l’espèce soit interdite en Corée du Nord depuis 1959 et que l’espèce soit inscrite à l’Annexe I de la Convention sur le commerce international des espèces de faune et de flore sauvages menacées d’extinction (CITES), les loutres eurasiennes sont capturées de manière opportuniste par des chasseurs nord-coréens pour le commerce illégal d’espèces sauvages pour des acheteurs de République populaire de Chine (Chine). Les peaux de loutres se vendraient à un prix élevé, par rapport à celles des autres animaux à fourrure, sur le marché noir. Les loutres eurasiennes seraient également élevées pour leur fourrure par l’État nord-coréen en vue d’un commerce international destiné à la Chine, et potentiellement à usage domestique. Nous tenons à mettre en évidence le fait que le commerce signalé peut enfreindre les engagements de la Chine envers la CITES et devrait être traité en priorité.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: El Comercio de Nutria Eurasiática Lutra lutra en Corea del Norte

En África viven cuatro especies de nutria (Carnivora: Mustelidae), de las cuales la nutria sin uñas Africana (Aonyx capensis) y la nutria de cuello manchado (Hydrictis maculicollis) se sabe que ocurren en Namibia, aunque se conoce muy poco sobre su biología y distribución. Ambas especies están listadas como Casi Amenazadas por la Lista Roja de Especies Amenazadas de UICN, debido a que se ha informado una declinación de sus números. Determinamos la presencia de la especie en los ríos Kunene y Okavango, registrando avistamientos de las nutrias sin uñas Africana y la de cuello manchado, realizados por la comunidad, así como signos (huellas y letrinas). Adicionalmente, desplegamos 4 cámaras-trampa a lo largo de las barrancas del Río Okavango en el Parque Nacional Bwabwata, en el invierno de 2022, obteniendo datos de un total de 967 días-cámara. En base a esto, calculamos un índice de abundancia relativa (RAI en el texto en inglés) de 0.3 para la nutria sin uñas Africana. El RAI para el Río Okavango fue el más bajo comparado con estudios similares conducidos en otras seis áreas naturales en Sudáfrica. Hay una necesidad evidente de conservación de los humedales y de restauración de la calidad del agua en la región. Adicionalmente, se recomienda la realización de estudios más expansivos de la taxonomía, distribución, dieta, y densidad poblacional de las nutrias que viven en todos los ríos perennes del norte de Namibia, como pasos importantes para asegurar el futuro de las nutrias en Namibia.

Vuelva a la tapa