IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Volume 40 Issue 1 (January 2023)

Citation: Okamoto, Y., Shepherd, C.R., and Sasaki, H. (2024). The Current Status of Regulation of Asian Small-Clawed Otters Aonyx cinereus Trade in Japan. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 41 (1): 4 - 14

The Current Status of Regulation of Asian Small-Clawed Otters Aonyx cinereus Trade in Japan

Yumiko Okamotoa1, 2*, Chris R. Shepherd2, 3, and Hiroshi Sasaki2, 4

1WWF Japan, 3F. Mita Kokusai Bldg., 1-4-28 Mita, Minato-ku, Tokyo, 108-0073, Japan

2IUCN SSC Otter Specialist Group

3Monitor Conservation Research Society, Big Lake Ranch, B.C., Canada

4Chikushi Jogakuen University, 2-12-1 Ishizaka, Dazaifu, Fukuoka 818-0192, Japan

*Corresponding Author Email: yumiko.okamoto@wwf.or.jp

Received 6th July 2023, accepted 14th August 2023

Abstract: The Asian Small-clawed Otter Aonyx cinereus is traded internationally to supply demand for pets, both legally and illegally. In 2019, the species was elevated from being listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) to Appendix I, which generally prohibits international trade, as trade was deemed a threat to the conservation of this species. Although the Japanese national legislation strictly protects the CITES Appendix I-listed species, it is still possible to trade the Asian Small-clawed Otters domestically, subject to the necessary registration procedures. Here we look at current trade levels of Asian Small-clawed Otters in Japan and the impact of the CITES up-listing.

Keywords: CITES, conservation, exotic pets, law enforcement, Mustelidae, wildlife trade

Illegal and/or unsustainable trade in wildlife is a threat to the survival of an increasingly long list of species (Eaton et al., 2015; Marshall et al., 2020). Among these are the 13 extant species of otters in the world, many of which are threatened due to demand for pelts, parts for use in traditional medicines, and as pets (Duplaix and Savage, 2018). Perhaps the most heavily traded otter species to supply demand for pets is the Asian Small-clawed Otter Aonyx cinereus (Gomez and Bouhuys, 2018). Found throughout much of East, South and Southeast Asia (Wright et al., 2021), the Asian Small-clawed Otter is assessed as Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and is reported to be threatened by habitat loss, loss of prey and increasing trade (Wright et al., 2021). This species is frequently found in international wildlife markets, on online trade platforms and displayed in animal cafes (Aadrean, 2013; Gomez et al., 2016; Gomez and Bouhuys, 2018; Kitade and Naruse, 2018; Siriwat and Nijman, 2018, Sigaud et al., 2023). Its small size, active behaviour, and attractive appearance have made it a favourite among exotic pet keepers, and by extension, among poachers and wildlife traffickers. Due to the imminent threat to its survival from illegal and unsustainable trade, the Asian Small-clawed Otter was listed in 2019 in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) which generally prohibits international trade, elevated from Appendix II. Since then, there has been one import only for scientific purposes, and no seizure records were reported in the CITES Trade Database (htpps://trade.cites.org) or TRAFFIC’s Wildlife Trade Information System (WiTIS) in Japan. The Asian Small-clawed Otter is protected as an "Internationally Rare Species of Wild Fauna and Flora" under domestic law in Japan, and since the Appendix I listing, legislation regulating the trading of Asian Small-clawed Otters has become rigid. However, Asian Small-clawed Otters obtained prior to the regulation or animals bred in captivity using individuals obtained prior to the regulation can still be traded for commercial purposes under individual otter registration with the Ministry of the Environment. This study focuses on the current status of pet otters regulation in Japan following the elevation of this species from Appendix II to Appendix I of CITES.

METHODS

To better understand the current status of otter trade in Japan, and the impact listing the species in CITES Appendix I in 2019 has had, we have carried out the following:

- We analysed international trade data from the CITES Trade Database to determine the past and recent role of Japan in the international trade in Asian Small-clawed Otters.

- We looked at trade levels prior to and after the up-listing of the species from CITES Appendix II to Appendix I in 2019 to determine changes in trade levels.

- We investigated the current levels of trade in Asian Small-clawed Otters for pets in Japan.

- We looked for recent enforcement records relating to the illegal trade in this species.

- We looked into the current demand and use of Asian Small-clawed Otters in animal cafes in Japan.

- We explain the new legislation in Japan to regulate and control the trade in Asian Small-clawed Otters to better understand the strengths and weaknesses of this legislation and the potential impacts it will have on the trade in this species.

- Finally, we have made recommendations to further prevent the illegal trade in Asian Small-clawed Otters in Japan.

RESULTS

Past Pet Otter Trade and Changes in CITES Regulations

International trade of live Asian Small-clawed Otters

International trade in the Asian Small-clawed Otter is not new. In the past, many Asian Small-clawed Otters were exported from Thailand to the United States of America and the United Kingdom for pets before Thailand stopped the export in the mid-1970s (Foster-Turley, 1992). Between 1977 and 2019, a total of 1160 live individuals had been traded worldwide for all purposes as reported by importing countries in the CITES Trade Database (Table 1). Of this total, 681 otters were traded for personal use and commercial trade (Purpose codes P and T, respectively) (Table 2). During this period, Japan imported the largest number of live individuals (n = 354), while the Netherlands exported the largest number of live individuals (n= 110).

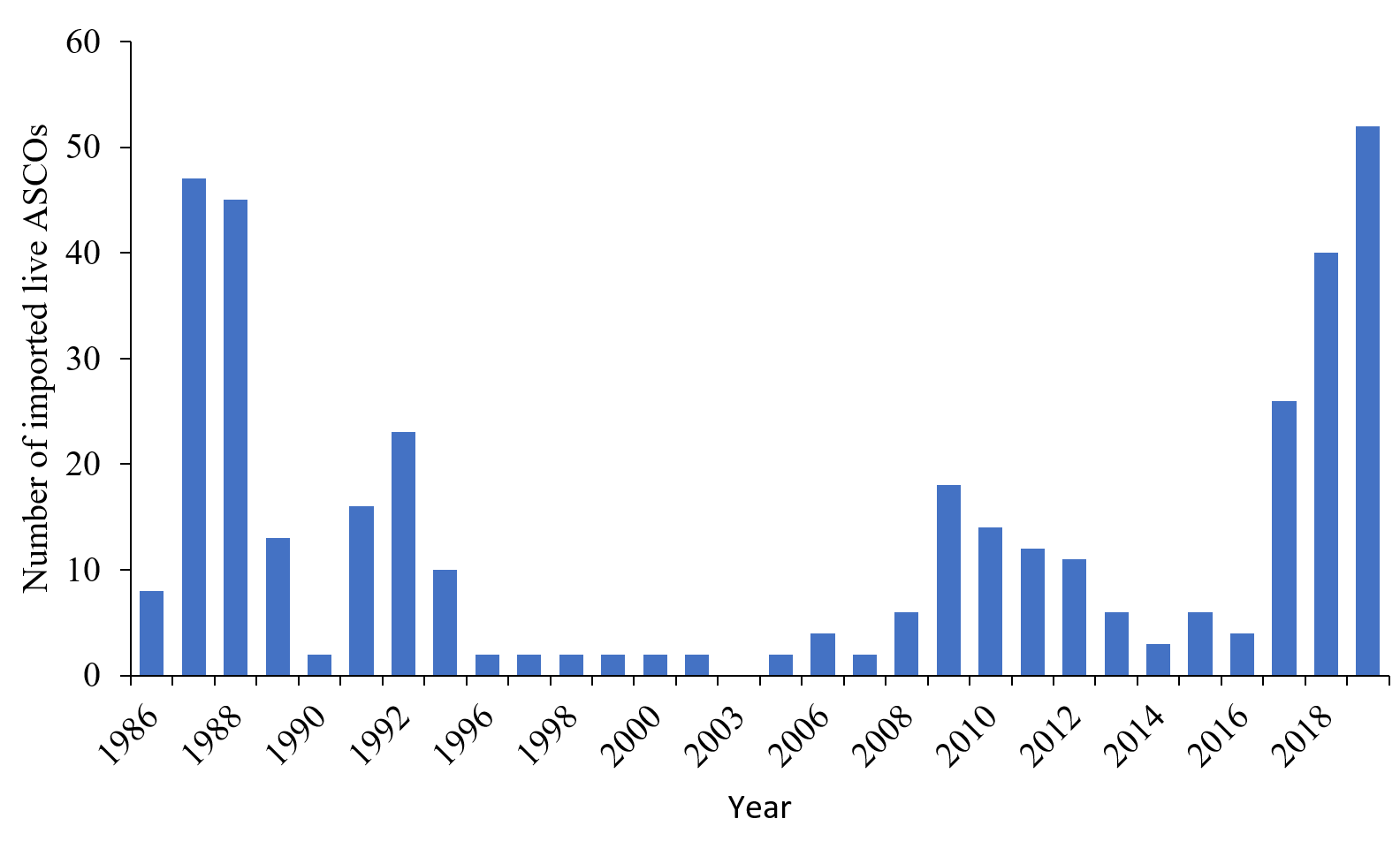

Import of Live Asian Small-clawed Otters to Japan

There were 382 live Asian Small-clawed Otters imported into Japan between 1986 and 2019 for all purposes, but since 2020, there has been one import only for scientific purposes, and no illegal imports of this species were reported in Japan. Imports increased in the latter half of the 1980s and again in the latter half of the 2010s (Figure 1). During the first peak in the latter half of the 1980s, most were imported for commercial purposes. As it was not common to keep otters as pets in households at that time, it is likely that demand came from zoos and aquariums that used the species in exhibitions. Asian Small-clawed Otters began to be kept in zoos and aquariums in Japan in 1970. Although a total of four individuals were exhibited in two zoos at first (Japanese Association of Zoos and Aquariums, 1970), the number of individuals in zoos and aquariums increased to 22 by 1995, and there were 228 in total in 39 facilities in 2013. It has been suggested that this increase was due to the Asian Small-clawed Otters being considered attractive as exhibition animals, that they were easy to obtain, and allegedly breed throughout the year with relatively large litter sizes (Wakiguchi, 2015).

Illegal Trade of Live Asian Small-clawed Otters in Asia and Japan

The high demand and increasing profits to wildlife traders has led to an increase in illegal trade in this species. In Southeast Asia, 32 live Asian Small-clawed Otters were seized between 2015 and 2017, with Thailand as the major hub of illegal trade (Gomez and Bouhuys, 2018). There was an increase in the trafficking of this species into Japan with at least 10 cases of smuggling or attempted smuggling of 62 Asian Small-clawed Otters into the country, largely from Indonesia and Thailand between 2000 to 2019 (Shepherd and Tansom, 2013; Kitade and Naruse, 2018). It is reasonable to assume that these seizures represent a mere fraction of the actual number of Asian Small-clawed Otters trafficked from a range of countries into Japan and, continued seizures and arrests indicate profitable incentives for successfully smuggling otters into Japan’s market (Kitade and Naruse, 2018).

Up-Listing to CITES Appendix I in 2019

In 1977, the Asian Small-clawed Otter was listed in Appendix II of the Convention on CITES (UNEP-WCMC, 2022). However, the Parties decided to list the Asian Small-clawed Otter in Appendix I in August 2019, as excessive trade due to escalating demand for pets would increase the risk of extinction of this endangered species. As a result, international commercial transactions have been prohibited in principle since 26 November 2019.

Current Situation of Pet Otter Trade

International Trade of Live Asian Small-Clawed Otters

Since the Asian Small-clawed Otter was listed in CITES Appendix I, international trade for commercial purposes of this species has been prohibited in principle, with possible exceptions for animals bred in captivity at facilities registered with CITES. Trade for scientific purposes is still allowed with permissions issued by the government of both the exporting and importing countries. Based on the CITES trade database between 2020 to 2021, one import for commercial purposes from the Czech Republic to South Korea was reported in 2021 (Table 3). However, as there are no breeding facilities in the world registered with CITES for this species, it is unclear how this trade was conducted.

While the international trade of the species into Japan has declined since the CITES Appendix I listing, there are still reports of illegal trade in some range states. According to TRAFFIC’s WiTIS, there were a total of 16 seizures involving 54 live Asian Small-clawed Otter reported from November 26th 2019 until December 31st 2021. There were eight seizures with a total of 34 live Asian Small-clawed Otters in Vietnam, and eight seizures with a total of 20 live Asian Small-clawed Otters in Thailand. In most of the cases, advertisements of live otters for sale as pets were posted on social media such as Facebook.

The Asian Small-clawed Otter is protected under domestic laws in all Southeast Asian countries except Cambodia and Indonesia, with the latter regulating trade on paper under a national quota system (Gomez and Bouhuys, 2018). However, as can be seen from these data, illegal trade persists in many countries despite national laws.

Law Enforcement and Market of Pet Otters in Japan

Due to elevation of the Asian Small-clawed Otter from Appendix II to I of CITES, the species has become subject to protection under domestic legislation in Japan, and regulations on management have changed significantly. Individual otter registration with the Ministry of the Environment is now required for transaction or display for sale or distribution purposes.

However, the number of animal cafes exhibiting otters whose operation is legally allowed in Japan has increased slightly since 2018. It can be seen from Google Trends that general interest in otters in Japan remains at a high level, and the “demand” for keeping otters as pets still exists. As it has been pointed out that Japanese social media posts calling for galagos to be pets are stimulating demand for pets globally (Svensson et al., 2022), the pet demand of the Asian Small-clawed otters in Japan could indirectly increase threats to the conservation of wild populations. In addition, there are concerns about animal welfare because the act of “petting” can cause physical and mental stress to animals, and animals may be placed in environments different from their natural habitats.

Legislation

Legal regulations regarding the Asian Small-clawed Otter in Japan were introduced through the Act on Conservation of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora 1992 (ACES) and the Act on Welfare and Management of Animals 1973, which are the primary laws regarding domestic trade and keeping of animals.

- Act on Conservation of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (ACES)

The ACES is a law enacted in 1992 to conserve species that are designated as nationally endangered species as well as internationally threatened species listed in CITES Appendix I, or Conventions and Agreements for Protection of Migratory Birds. Accordingly, the Asian Small-clawed Otter was designated as an Internationally Rare Species of Wild Fauna and Flora under ACES from November 26th, 2019, onwards. In principle, the transaction referring to transfers (giving, selling, lending, receiving, buying, and borrowing) of endangered species is prohibited. Display and advertising for the purpose of sale or distribution leading to a transaction are also subject to regulation. Therefore, to transact, display or advertise for individuals that meet certain conditions such as being obtained prior to the application of ACES regulations or animals bred in captivity using individuals obtained prior to ACES regulations, each Asian Small-clawed Otter must be individually registered through the designated institution by the Ministry of the Environment of Japan. Additionally, a registration card showing the registration number, registration date, and expiration date must be provided during the transaction or display and advertising for sale or distribution. - Act on Welfare and Management of Animals

The Act on Welfare and Management of Animals was enacted in 1973 and stipulates standards for the care and management of animals to ensure their health and safety and prevent animals from causing harm or inconvenience to humans. This law is not related to CITES implementation, and therefore, the regulation of the Asian Small-clawed Otter under this law has not changed. However, the Act on Welfare and Management of Animals stipulates various regulations regarding businesses dealing with animals, and face-to-face explanations and physical confirmation of animals are required for dealers when selling mammals, birds, and reptiles to customers, restricting the online trade in Asian Small-clawed Otters in Japan.

Market

Once a species is listed in Appendix I of CITES, international trade is prohibited in principle. In the case of the Asian Small-clawed Otter, no import record to Japan has been confirmed since 2019. Many cases of sales of otters at exotic pet fairs or online advertisements were observed in Japan before the change (Kitade and Naruse, 2018), but as of 2022, multiple dealers say on their websites that they have suspended their sale of otters because it has become difficult to import otters.

However, there are still several shops or animal cafes selling or leasing otters bred in captivity with registration numbers. In 2020, the number of Asian Small-clawed Otters registered by the Ministry of the Environment of Japan was 31, and as of July 2022, it was 95. Although it is thought that the quantity of otters on the pet market in Japan has decreased significantly due to import restrictions, this indicates that there are still some otters being traded within Japan.

Otter Cafes

From the latter half of the 2000s, the overall pet trade and posts on social media platforms of the Asian Small-clawed Otters has increased, likely encouraged by the fact that this species was featured as a cute “pet” in local TV programmes in Japan (Kitade and Naruse, 2018). Furthermore, in Japan, Asian Small-clawed Otters are not only kept as household pets but are also in demand for display at animal cafes (Kitade and Naruse, 2018; McMillan, 2018), some known as otter cafes, indicating the popularity of these animals.

Otter cafes usually offer otters on display and petting opportunities, but some facilities also legally breed and sell individuals by highlighting the “cuteness” of otters. In addition to stimulating demand, there are also concerns about animal welfare and public health related to keeping animals at these cafes. In many facilities, otters are placed in small spaces without swimming facilities and fed mainly cat food, which is not considered to be a sufficient or nutritional diet according to a nutritional study of the species (Cabana et al., 2022). There have been reports of health problems in some otters kept at these cafes that are thought to be likely caused by a lack of proper care and the stress of constant interactions with customers (Okamoto et al., 2020). Furthermore, eating and drinking by customers in direct contract with wild animals, such as otters, likely increases the risk of zoonotic diseases (Sigaud et al., 2023).

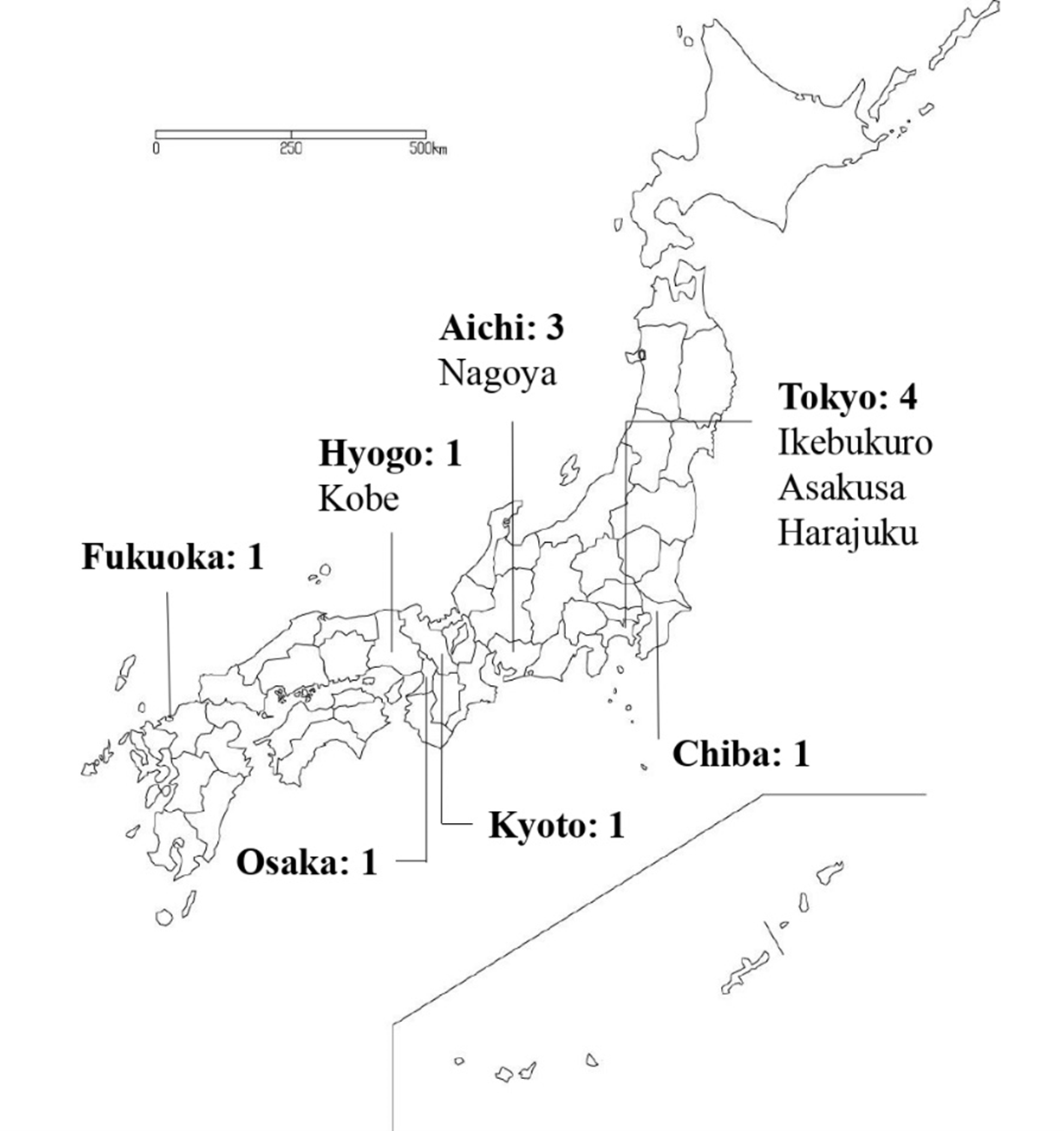

We investigated the current situation of otter cafes, which are believed to have a major impact on stimulating demand for otters as pets. As of July 2022, Asian Small-clawed Otters were exhibited at 12 otter cafes in seven cities, with the largest number of four otter cafes in Tokyo (Figure 2). This data shows the number of otter cafes has increased slightly compared to the number of ten facilities observed by TRAFFIC in 2018 (Kitade and Naruse, 2018).

Demand for Pet Otters

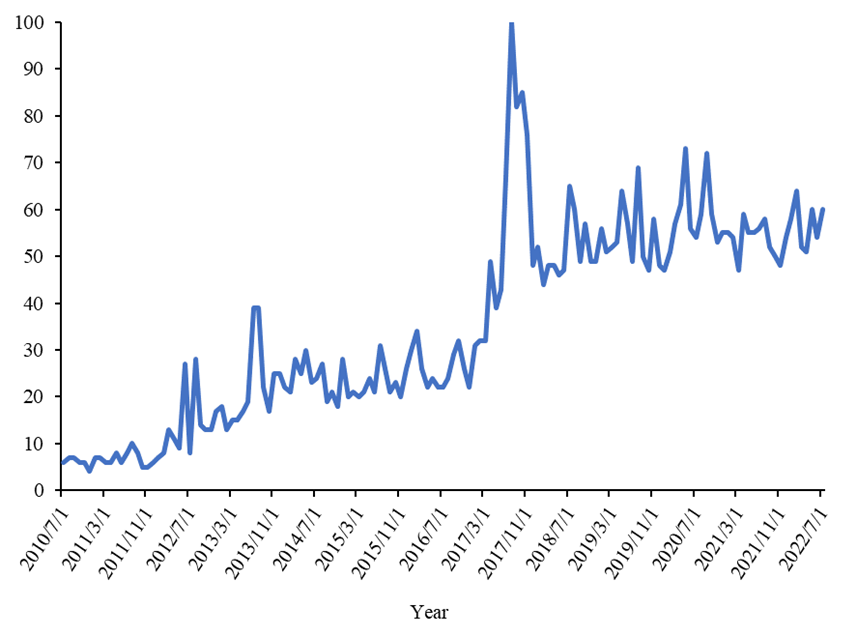

To understand the trends in the general public’s interest in otters in Japan, we searched for the word “カワウソ” (meaning “otter” in Japanese) from July 1, 2010, to July 1, 2022, using Google Trends (Figure 3). The search frequency of this word gradually increased from around 2013, peaked in August 2017, and was about half of the peak in November 2019 when the Asian Small-clawed Otter was listed in Appendix I of CITES.

Since the search trends include searches for other purposes, it is impossible to know the accurate demand for Asian Small-clawed Otters as pets. However, it is inferred that the general public in Japan still has a high interest in this species.

CONCLUSION

Since the inclusion of Asian Small-clawed Otters in Appendix I of CITES in 2019, the international trade volume of Asian Small-clawed Otters has decreased markedly. However, in many parts of the Asian region, illegal domestic trade is still conducted mainly on online platforms.

Japan, historically one of the major consuming countries for Asian Small-clawed Otters as pets, has had no new reports of imports or smuggling since it was listed in CITES Appendix I, according to CITES and WiTIS records. It became significantly difficult for dealers to trade this species due to significant decline in import volumes and tightening regulations under Japanese domestic law, and the number of advertisements of otters for sale seems to have decreased.

Individuals imported before the tightening of regulations and their offspring can still be traded if they are registered with the government. Some dealers sell captive-bred individuals, so a certain amount of pet use is expected to continue in the future. This should be closely monitored to prevent unscrupulous trade to other countries with demand for this species.

Social media and animal cafe exhibits are the main drivers creating demand for pet otters and other exotic pets. In particular, there are many concerns about animal cafes, which display wild animals such as otters, not only from the perspective of stimulating demand but also from the perspective of animal welfare and public health.

Efforts should be made to continue to reduce demand for Asian Small-clawed Otters in Japan and in all countries where this threatened species is traded. Specifically, it would be effective for the private sector to eliminate displays of this species at animal cafes, which may stimulate demand for pets. Demand is also expected to be reduced if appropriate information, including the threatened situation of Asian Small-clawed Otters and the impact of trade, is conveyed to consumers on social media or the mass media, eliminating messages that encourage them to keep this species as pets. In addition, researchers around the world will help foster social momentum to reduce demand for Asian Small-clawed Otters as pets by clarifying pet use and its adverse effects on this species.

Listing the Asian Small-Clawed Otter in Appendix I of CITES has led to a rapid reduction in legal international trade and seizure records. However, as illegal trade is still being reported in the country of origin, crackdowns should be strengthened by further clarifying and publicizing cases of illegal trade, seizures, and resulting prosecutions by the authorities of each country. Furthermore, care should be taken not to shift demand and trade of this species from countries with tighter regulations to countries with looser regulations and enforcement.

Acknowledgements: We thank Loretta Shepherd, Melissa Savage and Lalita Gomez for very helpful comments and edits on a previous draft. We also thank Naoya Ohashi for his help in finding references.

REFERENCES

Aadrean, A. (2013). An Investigation of otters trading as pet in Indonesian online markets. J. Biologika. 2(1): 1-6. https://jurnalbiologika.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/aadrean-2013.pdf

Cabana, F., Douray, G., Yeo, T., Mathura, Y. (2022). No progression of uroliths in Asian small-clawed otters (Aonyx cinereus) fed a naturalistic crustacean-based diet for 2 years. J. Zoo. Wildlife. Med. 53(2): 331-338. https://doi.org/10.1638/2020-0101

Duplaix, N., Savage, M. (2018). The Global Otter Conservation Strategy. IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group, Salem, Oregon, USA. https://www.otterspecialistgroup.org/osg-newsite/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/IUCN-Otter-Report-DEC%2012%20final_small.pdf

Eaton, J. A., Shepherd, C. R., Rheindt, F. E., Harris, J. B. C., van Balen, S. (B.), Wilcove, D. S., Collar, N. J. (2015). Trade-driven extinctions and near-extinctions of avian taxa in Sundaic Indonesia. Forktail 31: 1-12. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5c1a9e03f407b482a158da87/t/5c3753f41ae6cffee0fab087/1547129845459/Trade-driven-extinctions.pdf

Foster-Turley, P. (1992). Conservation ecology of sympatric Asian otters Aonyx cinerea and Lutra perspicillata. Ph.D. thesis, Univ. of Florida, USA. https://archive.org/details/conservationecol00fost

Gomez, L., J. Bouhuys. (2018). Illegal otter trade in Southeast Asia. TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. https://www.traffic.org/publications/reports/illegal-otter-trade-in-southeast-asia/

Gomez, L., Leupen, B. T. C., Theng, M., Fernandez, K., Savage, M. (2016). An analysis of otter seizures in selected Asian countries (1980-2015). TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/2402/illegal-otter-trade-asia.pdf

Japanese Association of Zoos and Aquariums. (1970). Japanese Zoos and Aquariums Annual Report. Japanese Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Tokyo.

Kitade, T., Naruse, Y. (2018). Otter Alert: a rapid assessment of illegal trade and booming demand in Japan, TRAFFIC, Japan. https://www.traffic.org/publications/reports/asian-otters-at-risk-from-illegal-trade-to-meet-booming-demand-in-japan/

Marshall, B. M., Strine, C., Hughes, A. C. (2020). Thousands of reptile species threatened by under-regulated global trade. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18523-4

McMillan, S. E. (2018). Too Cute! The Rise of Otter Cafes in Japan. Journal of the International Otter Survival Fund. 4: 23–28. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325709872_Too_cute_The_rise_of_otter_cafes_in_Japan

McMillan, S. E., Dingle, C., Allcock, J. A., Bonebrake, T. C. (2020). Exotic animal cafes are increasingly home to threatened biodiversity. Conserv. Lett. 14(6): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12760

Okamoto, Y., Maeda, N., Hirabayashi, M. and Ichinohe, N. (2020). The Situation of Pet Otters in Japan – Warning by Vets IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 37 (2): 71 – 79 https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume37/Okamoto_et_al_2020.html

Shepherd, C. R., Tansom, P. (2013). Seizure of live otters in Bangkok Airport, Thailand. IUCN Otter Spec Group Bull. 30(1): 37-38. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume30/Shepherd_Tansom_2013.html

Siguad, M., Kitade, T., Sarabian, C. (2023). Exotic animal cafés in Japan: A new fashion with potential Implications for biodiversity, global health, and animal welfare. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 5(2): 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.12867

Siriwat, P., Nijman, V. (2018). Illegal pet trade on social media as an emerging impediment to the conservation of Asian otter species. J. Asia-Pac. Biodivers. 11(4): 469-475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japb.2018.09.004

Svensson, M. S., Morcatty, T. Q., Nijman, V., Shepherd, C. R. (2022). The next exoic pet to go viral. Is social media causing an increase in the demand of owning bushbabies as pets? Hystrix. 33(1): 51-57. https://doi.org/10.4404/hystrix-00455-2021

UNEP-WCMC (Comps.) (2022). The Checklist of CITES Species Website. CITES Secretariat, Geneva, Switzerland. Compiled by UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, UK. Available at: http://checklist.cites.org. Accessed on June 2nd 2022.

Wakiguchi, K. (2015). An essay on the economics of Zoos and aquariums from the otter’s perspective. Human Social studies (Sagami Women’s University Bulletin). 12: 161-172 (In Japanese).

Wright, L., de Silva, P.K., Chan, B., Reza Lubis, I., Basak, S. (2021). Aonyx cinereus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: Available at: https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T44166A164580923.en. Accessed on June 1st 2022.

Résumé: État Actuel de la Réglementation du Commerce des Loutres Cendrées Aonyx cinereus au Japon

La loutre cendrée, Aonyx cinereus, est l’objet d’un commerce international en vue de répondre à la demande d’animaux de compagnie, à la fois légalement et illégalement. En 2019, l'espèce est passée de l’Annexe II de la Convention sur le commerce international des espèces de faune et de flore sauvages menacées d’extinction (CITES) à l’Annexe I, qui interdit généralement le commerce international, car son commerce est considéré comme une menace pour la conservation de l’espèce. Bien que la législation nationale japonaise protège strictement les espèces inscrites à l’Annexe I de la CITES, il est toujours possible de commercialiser la loutre cendrée au niveau national, sous réserve de procédures d’enregistrement nécessaires. Nous examinons ici les niveaux actuels du commerce des loutres cendrées au Japon et l’impact de leur inscription aux annexes de la CITES.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: El Estado Actual de la Regulación del Comercio de Nutrias de Uñas Pequeñas Asiáticas Aonyx cinereus en Japón

La Nutria de Uñas Pequeñas Asiática Aonyx cinereus es comerciada internacionalmente para proveer a la demanda de mascotas, tanto legal como ilegalmente. En 2019, la especie fue elevada de estar listada en el Apéndice II de la Convención sobre el Comercio Internacional de Especies Amenazadas de Fauna y Flora Silvestres (CITES), al Apéndice I, que en general prohíbe el comercio internacional, ya que se estimó que el comercio es una amenaza a la conservación de ésta especie. Aunque la legislación nacional Japonesa protege estrictamente a las especies del Apéndice I de CITES, es aún posible comerciar internamente Nutrias de Uñas Pequeñas Asiáticas, sujeto a los necesarios procedimientos de registro. Aquí analizamos los niveles actuales de comercio de Nutrias de Uñas Pequeñas Asiáticas en Japón, y el impacto del cambio en el listado de CITES

Vuelva a la tapa