IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Volume 42 Issue 4 (August 2025)

Citation: Medina-Vogel, G., Soto-Ampuero, C., Delgado-Parada, N., Molina-Maldonado, G., and Calvo-Mac, C.. (2025). First Video Evidence of Interaction Between Introduced American Mink (Neogale vison) and Endangered Native Southern River Otter (Lontra provocax). IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 42 (4): 179 - 185

First Video Evidence of Interaction Between Introduced American Mink (Neogale vison) and Endangered Native Southern River Otter (Lontra provocax)

Gonzalo Medina-Vogel1,2,3,4*, Carla Soto-Ampuero4,5,6,7,8, Nicole Delgado-Parada3,4,6,8,9, Gabriela Molina-Maldonado4,9, and Carlos Calvo-Mac1,3,4

1Instituto One Health, Facultad de Ciencias de la Vida, Universidad Andrés Bello, Chile

2Chile IUCN Species Survival Commission

3IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group, Gland, Switzerland

4Grupo Nutrias Chile

5Universidad de Los Lagos, Sede Puerto Montt, Campus Puerto Montt, Rengifo 477, Puerto Montt

6Movimiento Tarahuillín, Chonchi, Chiloé, Chile

7Red de Mujeres Originarias por la defensa del mar, Chile

8Isla Huillín, Chiloé, Chile

9Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, 340 Libertador Bernardo O’Higgins Avenue, Santiago 8370136, Chile.

*Corresponding Author Email: gmedina@unab.cl

Received 28th April 2025, accepted 23rd May

Abstract: The introduction of the American mink (Neogale vison) in southern Chile is a significant concern for the conservation of the southern river otter (Lontra provocax), especially in Patagonia, where both species overlap. This study provides the first documentation of close interaction between the two species, recorded by camera traps in the locality of Tarahuín, Chonchi municipality, Chiloé Island, Chile (South America). The encounter was characterized by aggressive behavior at close range and for a brief period of time, which may facilitate the indirect transmission of pathogens such as canine distemper virus (CDV) and canine parvovirus (CPV), especially around a latrine shared by wild carnivores. These findings indicate that American mink could act as a bridge host between domestic dogs and otters, and underscore the need to implement conservation strategies to mitigate their ecological and health effects.

Keywords: Coexistence, mustelids, spillover, carnivores, photo

INTRODUCTION

The American mink (Neogale vison), a semiaquatic mustelid native of the Nearctic region, has been introduced globally, including southern Chile and Argentina, where it occupies both freshwater and marine habitats (Fasola et al., 2021). In southern Chile, the American mink coexists with the endangered native southern river otter (Lontra provocax) (Medina, 1997; Medina et al., 2023; 2024), whose presence has been confirmed in different areas of Chiloé Island in recent years (Delgado et al., 2024; Medina-Vogel et al., 2024). The southern river otter, a species that can be up to ten times larger than the American mink, influences the mink’s habitat use, diet, and circadian activity (Medina-Vogel et al., 2013). Similarly, Eurasian otters (Lutra lutra) have been documented attacking and killing American mink (Bonesi and Macdonald, 2004; Simpson, 2006). In the United Kingdom, the presence of the Eurasian otters has been shown to affect the distribution and population density of American mink (Bonesi and Macdonald, 2004; Bonesi et al., 2006; McDonald et al., 2007), and to induce shifts in their diet (Clode and Macdonald, 1995; Bonesi et al., 2004; Harrington et al., 2009) as well as alterations in their circadian activity patterns (Harrington et al., 2009). However, such interactions and their effects have been rarely observed in Patagonia (Medina-Vogel et al., 2013). Indeed, Medina-Vogel et al., (2013) report only two instances of aggressive encounters between southern river otters and American mink, both of which ended with the mink fleeing. These findings suggest that American mink may actively avoid close encounters with southern river otters, though such interactions have never been directly recorded. Here we present the first recorded video evidence of a close encounter between an adult southern river otter and an adult American mink.

METHODS

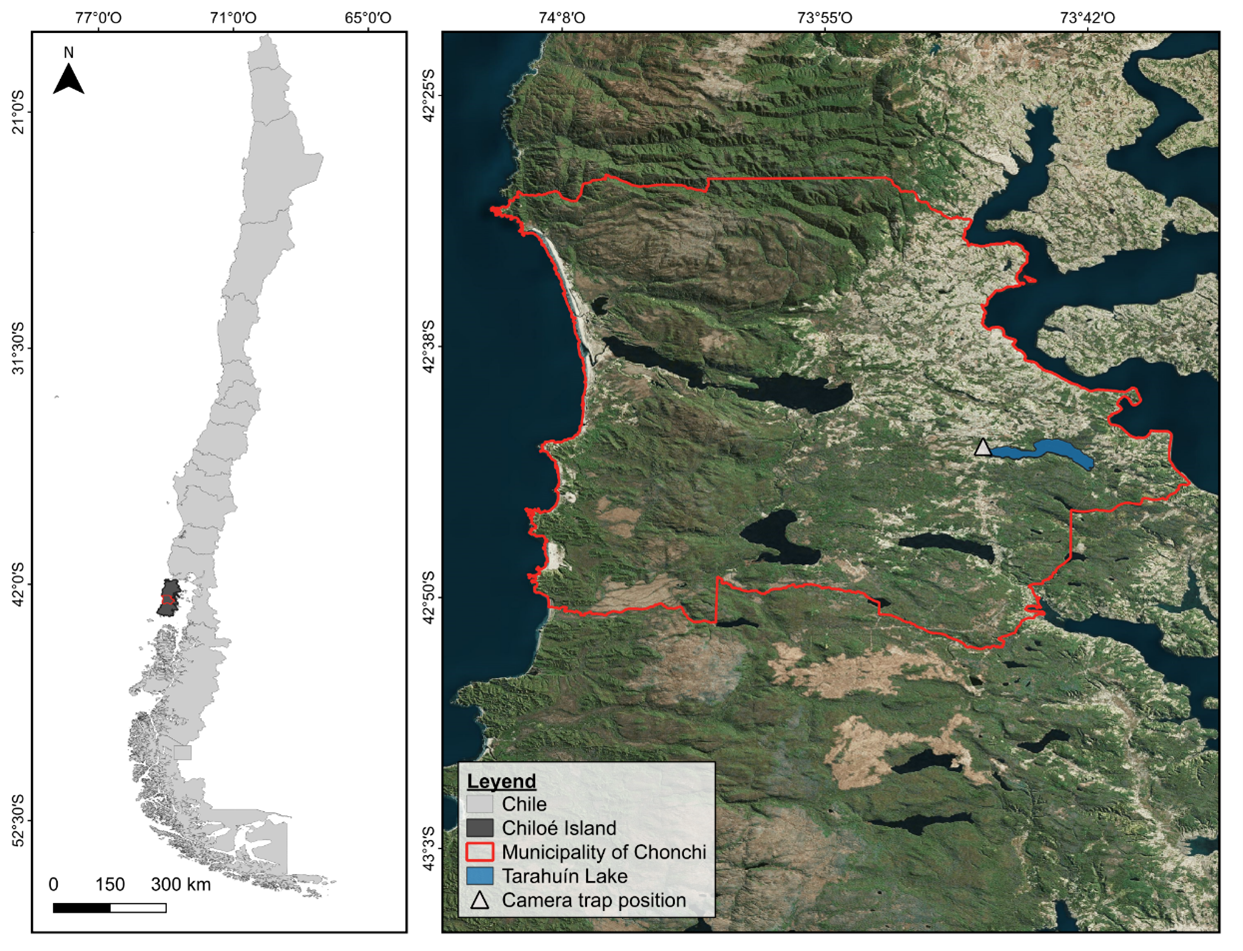

Between January 9th, 2025 and February 15th, 2025, we deployed a Suntekcam HC-801 series APP Control 4G 20MP 1080P camera trap, programmed to record video via motion detection. The camera was strategically positioned to monitor areas of known otter activity identified by the presence of tracks, feces, latrines, and burrows (Santibañez et al., 2024). The sampling site was located in the town of Tarahuín, municipality of Chonchi, Chiloé Island, Chile (South America), approximately five meters from the road connecting the municipalities of Chonchi and Quellón, near Lake Tarahuín (Fig. 1). This location has been under camera monitoring for nearly a year. The area features caves and latrines beneath cement blocks, remnants of an old gravel road destroyed by an earthquake. The camera was installed within one of these structures.

RESULTS

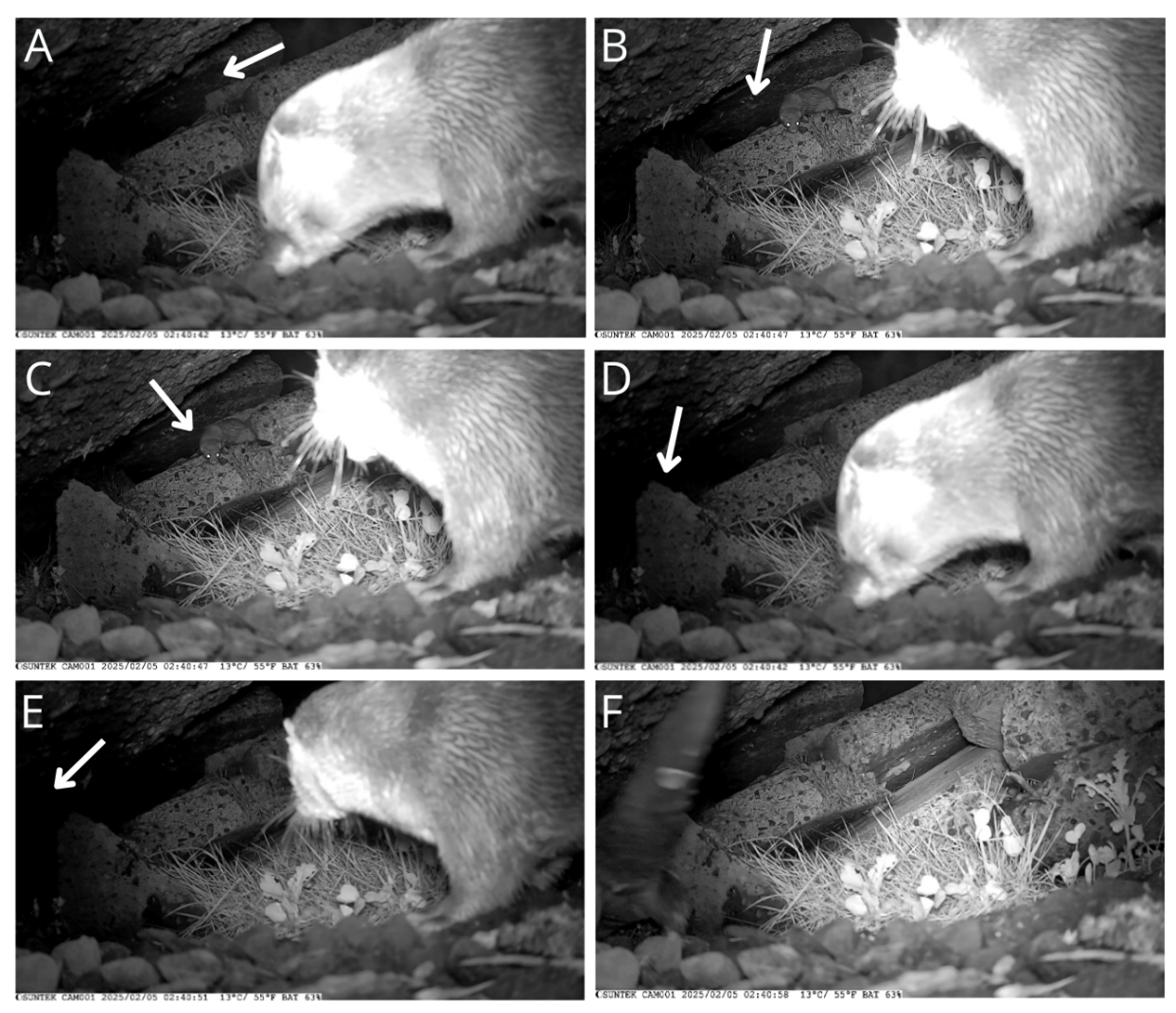

A video lasting 30 seconds was recorded on February 5, 2025, at 2:40 am. The footage captured a close interaction, occurring at an approximate distance of one meter, between a single otter and a mink. The video begins with a male otter sniffing around a defecation site when the mink appears in its vicinity (Fig. 2A, B ). The mink approached the otter (Fig. 2C), prompting the otter to respond with what appeared to be a growl (Fig. 2B, C). Following this interaction, the mink responded by moving away (Fig. 2D) and the otter then chased it into the tunnels under the rocks (Fig. 2E, F). No remains of food or prey are seen.

Download the video (MP4 4.3 MB)

DISCUSSION

The introduction of alien species, such as the American mink, can have significant implications for native wildlife, including acting as amplifiers of infectious diseases or as reservoirs for pathogens that might not otherwise persist in low-density populations of southern river otters (Barros et al., 2022). Direct or indirect contact between these species is critical for the spillover of diseases such as Parvovirus and canine distemper virus. Canine parvovirus (CPV), a DNA virus from the Parvoviridae family, is highly resistant to environmental conditions, capable of surviving up to six months at room temperature (Parrish, 1990; Williams, 2001). CPV has been associated with mortality in captive mustelids (Gjeltema et al., 2015), raising concern about its potential impact on the viability of southern river otter populations. Similarly, canine distemper virus (CDV), an RNA virus of the Morbillivirus genus in the Paramyxoviridae family, is highly contagious among carnivores (Hammer et al., 2007). It spreads rapidly within mustelid populations and causes high mortality rates in unvaccinated mink (Hammer et al., 2007). Consequently, CDV represents a serious health threat to southern river otter populations (Barros et al., 2022).

The population density of American mink, as well as their interactions with southern river otters, likely play a pivotal role in shaping the transmission of infectious diseases like CDV and CPV. Serological and molecular studies suggest that mink may act as bridge hosts, facilitating the transmission of pathogens from domestic dogs to wild otter populations in Chile (Sepúlveda et al., 2014; Barros et al., 2022). For instance, Barros et al. (2022) recorded a strong positive correlation between dog population density and observed seroprevalence of CDVs in dogs, mink, and southern river otters. However, for CPV, seroprevalence in mink and otters was not directly correlated with higher dog population density. Instead, it was influenced by interactions between dog and mink population densities and their social behavior (Barros et al., 2022). Hierarchy and territorial behaviors, which are characteristic of both otters and mink, can also affect disease transmission dynamics, particularly at low population densities and disease prevalence (Davidson et al., 2008, Powell, 2000).

The video evidence presented in this study captured a close, indirect interaction between a mink and a southern river otter, at less than one meter distance and for a short time interval (under one minute). Although no direct contact was observed, this type of interaction, especially around shared latrines, may present opportunities for indirect pathogen transmission. Pathogens such as CDV and CPV are known to remain viable in the environment under such conditions (Shen and Gorham, 1980; Parrish, 1990; Williams, 2001). Similar spatial overlap, latrine co-use, and aggressive encounters between these two species have been documented in dog-free habitats (Medina-Vogel et al., 2013). These observations lend support to the hypothesis proposed by Sepúlveda et al. (2014) and Barros et al. (2022) that American mink may act as a bridge host for the transmission of CPV and CDV from domestic dogs to southern river otters. The recorded interaction between mink and otter documented in this study further corroborates this hypothesis, providing direct observational evidence of the feasibility of such pathogen transmission under natural conditions.

Acknowledgements - We would like to thank Carla Soto Ampuero and the Tarahuillín Movement, a socio-environmental organization from the locality of Tarahuín, municipality of Chonchi, Chiloé Island, Chile, for generously sharing the camera trap recordings, which were fundamental to the development of this study.

REFERENCES

Barros, M., Pons, D.J., Moreno, A., Vianna, J., Ramos, B., Dueñas, F., Coccia, C., Saavedra-Rodríguez, R., Santibañez, A., Medina-Vogel, G. (2022). Domestic dog and alien North American mink as reservoirs of infectious diseases in the endangered Southern river otter. Austral J Vet Sci. 54(2): 65-75. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0719-81322022000200065

Bonesi, L., Macdonald, D.W. (2004). Differential habitat use promotes sustainable coexistence between the specialist otter and the generalist mink. Oikos. 106: 509-519. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2004.13034.x

Bonesi, L., Strachan, R., Macdonald, D.W. (2006). Why are there fewer signs of mink in England? Considering multiple hypotheses. Biol Conserv. 130 (2): 268-277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.12.021

Clode, D., Macdonald, D.W. (1995). Evidence for food competition between mink (Mustela vison) and otter (Lutra lutra) on Scottish island. J. Zool. (Lond.). 237: 435–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1995.tb02773.x

Davidson, R. S., Marion, G., Hutchings, M. R. (2008). Effects of host social hierarchy on disease persistence. J Theor Biol. 253: 424-433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2008.03.021

Delgado-Parada, N., Molina-Maldonado, G., Medina-Vogel, G., Calvo-Mac, C. (2024). Potencial distribución del huillín (Lontra provocax) en la cuenca media y baja del río Chadmo, X Región, Chile. Informe técnico, Proyecto Acción Huillín. ONG Chile Protegido. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385343308_Potencial_distribucion_del_huillin_Lontra_provocax_en_la_cuenca_media_y_baja_del_rio_Chadmo_X_Region_Chile

Fasola, L., Zucolillo, P., Roesler, I., Cabello, J.L. (2021). Foreign Carnivore: The Case of American Mink (Neovison vison) in South America. In: Jaksic, F., Castro, S. (Eds.) Biological Invasions in the South American Anthropocene. Springer, Cham, Santiago, Chile, pp 255- 299. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56379-0_12

Gjeltema, J., Murphy, H., Rivera, S. (2015). Clinical canine parvovirus type 2C infection in a group of Asian small-clawed otters (Aonyx cinerea). J Zoo Wild Med. 46(1): 120-123. https://doi.org/10.1638/2014-0090R1.1

Hammer, A. S., Dietz, H. H., Hamilton-Dutoit, S. (2007). Immunohistochemical detection of 3 viral infections in paraffin-embedded tissue from mink (Mustela vison): a tissue-microarray-based study. Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research, 71(1): 8-13. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1635994/

Harrington, L.A., Harrington, A.L. and Macdonald, D.W. (2009). The Smell of New Competitors: The Response of American Mink, Mustela vison, to the Odours of Otter, Lutra lutra and Polecat, M. putorius. Ethol. 115: 421-428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.2008.01593.x

McDonald, R.A., O’Hara, K., Morrish, D.J. (2007). Decline of invasive alien mink (Mustela vison) is concurrent with recovery of native otters (Lutra lutra). Divers Distrib. 13: 92-98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1366-9516.2006.00303.x

Medina, G. (1997). A Comparison of the diet and distribution of southern river otter (Lutra provocax) and mink (Mustela vison) in Southern Chile. J Zool (Lond). 242: 291-297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1997.tb05802.x

Medina-Vogel, G., Barros, M., Organ, J.F. and Bonesi, L. (2013). Coexistence between introduced mink and native otter. J Zool (Lond). 290: 27-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/jzo.12010

Medina-Vogel, G., Calvo-Mac, C., Delgado-Parada, N., Molina-Maldonado, G., Johnson-Padilla, S., Berland-Arias, P. (2023). Co-Occurrence Between Salmon Farming, Alien American Mink (Neogale vison), and Endangered Otters in Patagonia. Aquat Mamm. 49(6): 561–568. https://doi.org/10.1578/am.49.6.2023.561

Medina-Vogel, G., Navarro-Vivar, D., Calvo-Mac, C. (2024). Assessment of the Distribution and Coexistence of Two Sympatric Otter Species in the Chiloé Archipelago, Chile, Using Photo-Identification. Aquat Mamm. 5(5): 423-429. https://doi.org/10.1578/AM.50.5.2024.423

Parrish, C. R. (1990). Emergence, natural history, and variation of canine, mink, and feline parvoviruses. Ad Virus Res. 38: 403-450. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60867-2

Powell, R.A. (2000). Animal home range and territories and home range estimators. In: Boitani, L., Fuller, T.K. (Eds) Research techniques in animal ecology. Columbia University Press, New York, pp 65-110. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/boit11340

Santibañez, A., Barría, E. M., Barros, M., Coccia, C., Medina-Vogel, G. (2024). First Detection of Lontra provocax in an Unexplored Hydrological Basin of Central-Southern Chile. Aquat Mamm. 50(1): 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1578/AM.50.1.2024.13

Sepúlveda, M. A, Singer, R. S, Silva-Rodríguez, E. A, Eguren, A., Stowhas, P., Pelican, K. (2014). Invasive American mink: linking pathogen risk between domestic and endangered carnivores. Ecohealth. 11(3): 409-419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-014-0917-z

Shen DT, Gorham JR. (1980). Survival of pathogenic distemper virus at 5C and 25C. Vet Med Small Anim Clin. 75(1): 69-72.

Simpson, V.R. (2006). Patterns and significance of bite wounds in Eurasian otters (Lutra lutra) in southern and south-west England. Vet Rec., 158(4):113-9. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.158.4.113

Williams, E. S. (2001). Canine Distemper. In E. S. Williams & I. K. Barker (Eds.) Infectious Diseases of Wild Mammals (3rd ed), Chapter 2 Morbilliviral Diseases. Iowa State University Press. pp. 50-59. ISBN: 9780813825564 https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470344880.ch2

Résumé: Première Évidence Vidéo d’une Interaction entre le Vison d’Amérique (Neogale vison) Introduit et la Loutre de Rivière du Sud (Lontra provocax), une Espèce Indigène Menacée d’Extinction

L’introduction du vison d’Amérique (Neogale vison) dans le sud du Chili est une préoccupation majeure pour la conservation de la loutre de rivière du sud (Lontra provocax), en particulier en Patagonie, où les deux espèces se chevauchent. Cette étude fournit la première documentation sur l’interaction étroite entre les deux espèces, enregistrée par des pièges photographiques dans la localité de Tarahuín, municipalité de Chonchi, île de Chiloé, Chili (Amérique du Sud). La rencontre s’est caractérisée par un comportement agressif à courte distance et pendant une courte période, ce qui peut faciliter la transmission indirecte d’agents pathogènes tels que le virus de la maladie de Carré (VMC) et le parvovirus canin (VPC), en particulier autour d’une latrine partagée entre carnivores sauvages. Ces résultats indiquent que le vison d’Amérique pourrait servir d’hôte intermédiaire entre les chiens domestiques et les loutres, et soulignent la nécessité de mettre en œuvre des stratégies de conservation afin d’atténuer ses effets écologiques et sanitaires.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Primera Evidencia en Video de la Interacción entre el Visón Americano Introducido (Neogale vison) y La Nutria de Río del Sur Nativa en Peligro de Extinción (Lontra provocax)

La introducción del visón americano (Neogale vison) en el sur de Chile es una preocupación importante para la conservación de la nutria de río del sur (Lontra provocax), especialmente en la Patagonia, donde ambas especies se solapan. Este estudio documenta por primera vez una interacción cercana entre ambas especies, registrada mediante cámaras trampa en la localidad de Tarahuín, comuna de Chonchi, Isla de Chiloé, Chile (Sudamérica). El encuentro se caracterizó por un comportamiento agresivo a corta distancia y durante un lapso breve, lo que puede facilitar la transmisión indirecta de patógenos como el virus del moquillo canino (VDC) y el parvovirus canino (CPV), especialmente alrededor de una letrina compartida entre carnívoros salvajes. Estos hallazgos indican que el visón americano podría actuar como hospedador puente entre perros domésticos y nutrias, y subrayan la necesidad de implementar estrategias de conservación para mitigar sus efectos ecológicos y sanitarios.

Vuelva a la tapa