IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Volume 35 Issue 4 (December 2018)

Citation: Giovacchini, S, Marrese, M and Loy, A (2018). Good News from the South: Filling the Gap between Two Otter Populations in Italy . IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 35 (4): 212 - 221

Good News from the South: Filling the Gap between Two Otter Populations in Italy

Simone Giovacchini1*, Maurizio Marrese2 and Anna Loy1

1 Dipartimento di Bioscienze e Territorio, Università degli Studi del Molise, Contrada Fonte Lappone, 86090, Pesche (IS), Italy

2Centro Studi Naturalistici ONLUS, via Vittime Civili 64, 71121, Foggia, Italy

* Corresponding Author: Email: simone.giovacchini@yahoo.com

Received 7th March 2018, accepted 28th June 2018

Abstract: Following a severe decline in Italy in the second half of the last century, the Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) has been confined in the southern part of the peninsula with two isolated nuclei. Similar to other European populations, a slow recovery of the two disjointed populations started in the 90s. Filling the range gap was set as a main objective of the national action plan released in 2011. To assess the achievement of this target we ran a systematic survey in 2017 in the gap area, searching for otter signs in two river basins and two lakes in the Tyrrhenian (Campania) and Adriatic (Puglia) portions of the gap area. Otters were detected along most of the hydrographic network surveyed in the Tyrrhenian side, and only in few sites in the Adriatic side. Results confirmed the gap filling between the two sub ranges, and highlighted the need for a habitat survey in the Adriatic water courses. Our results have implications for the long-term survival of the small and endangered otter population in Italy.

Keywords: Lutra lutra, Volturno river, Candelaro river, recovery.

INTRODUCTION

The Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) is one of the most threatened mammals in Italy, listed as Endangered in the IUCN Red List of Italian vertebrates (Rondinini et al. 2013). Once widespread in the whole peninsula (Giglioli, 1880; Cavazza, 1911; Ghigi, 1911; Bonelli and Moltoni, 1929), the otter started to decrease in the 1970s. The first national survey undertaken in 1971-1973 showed that the species was still widespread, but decreasing and showing a fragmented distribution in northern regions (Cagnolaro et al., 1975). Later investigations based on interviews with forestry service and hunting associations didn’t show any improvement of the otter status (Spagnesi and Cagnolaro, 1981; Pavan and Mazzoldi, 1983). The first direct field surveys run in the late 70s revealed that the otter was decreasing at an alarming rate (Wayre, 1976; Macdonald and Mason, 1983).

This situation led to a more accurate national systematic survey run between 1984 and 1985, coordinated by the WWF and sponsored by the Italian Ministry of Environment (Cassola, 1986). The survey returned an even more dramatic picture: the species was extinct in northern Italy, extremely reduced and fragmented in central Italy, and a viable population only survived in most southern regions (Basilicata and part of Calabria, Puglia and Campania), being completely isolated from any other European population (Cassola, 1986; Beseghi and Donati, 1987).

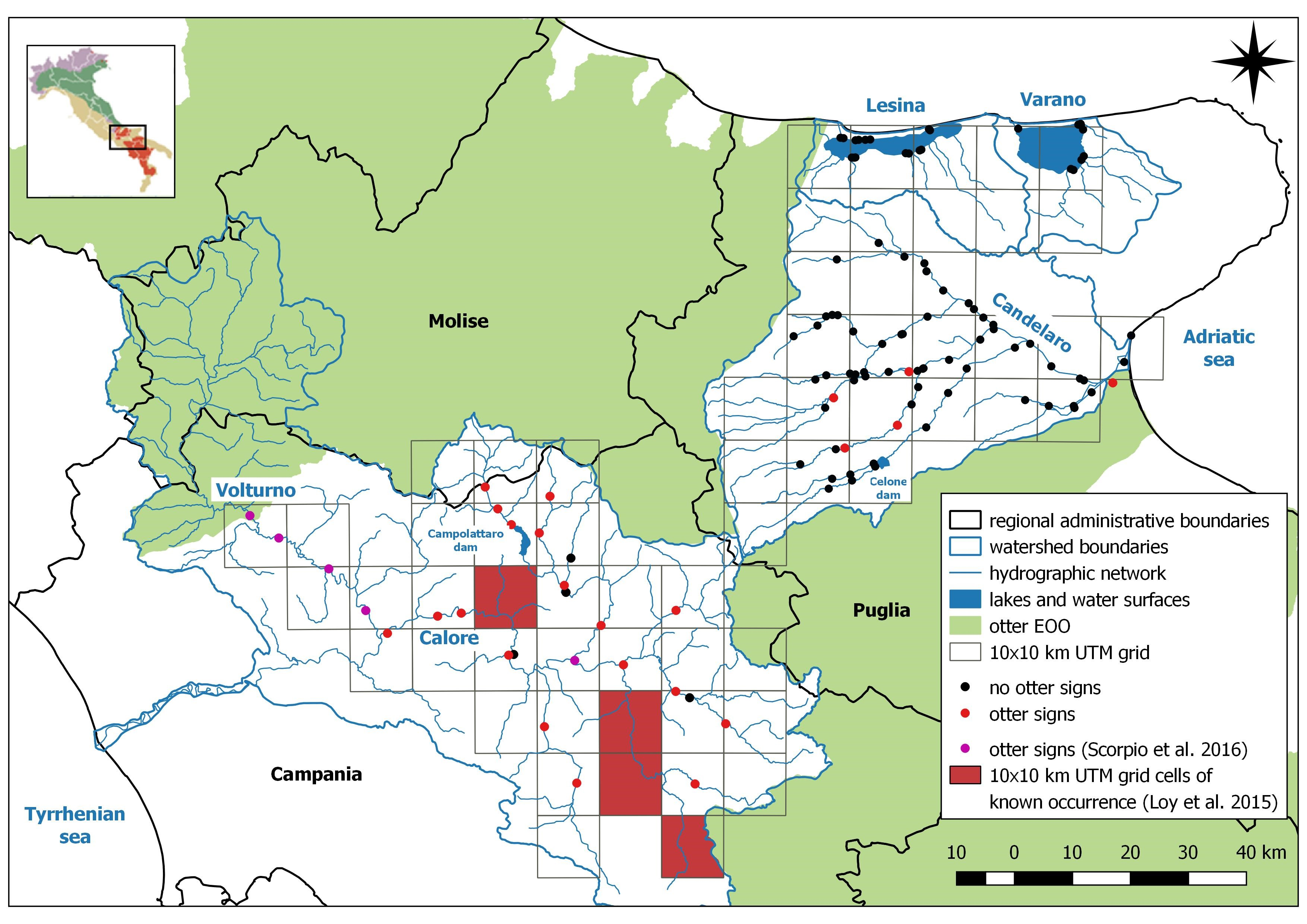

Thereafter, the use of standard survey techniques (Reuther et al., 2000) became more frequent and independent investigations detected the disappearance of all residual nuclei in central Italy (Prigioni et al., 1989; Reggiani et al., 1995, 2001; Mattei et al., 2001) while new occurrences were detected in some southern river basins (Reggiani and Ciucci, 1994; Agapito Ludovici et al., 1994). Systematic surveys run between 2002 and 2004 in southern Italy confirmed the presence of otters in the most southern regions, and the existence of a small isolated population in the central - southern region of Molise (Loy et al., 2004; Marcelli, 2006) (Fig. 1). To face this dramatic situation a national action plan was set up in 2011, aimed at increasing awareness, reducing threats, and supporting otter recovery (Panzacchi et al., 2011; Loy et al., 2010).

(click for larger version)

STUDY AREA AND METHODS

The study area covers about 9 300 km2 across the Apennine watershed (highest altitude in the area: 1 086 m) in southern Italy (Fig. 2), with streams flowing eastward to the Adriatic Sea and westward to the Tyrrhenian Sea. The Adriatic landscape is characterized by intensive agricultural lowland plains, where water bodies mainly comprise channels and lagoons. The western Tyrrhenian landscape is more heterogeneous and hilly, with rivers flowing in crops, riparian forests and woodlands (CORINE Land Cover, 2012). The average human density is 98/km-2 in the eastern part (63/km-2 excluding largest towns) and 148 km-2 in the western part (124/km-2 excluding largest towns) (data source: National Institute of Statistics, 2013).

(click for larger version)

The Volturno is a key river basin for the Italian otters (Panzacchi et al., 2011): it is one of the largest catchments of southern Italy, covering an area of 5 450 km2 and connecting 15 different water basins (Regione Molise, 2016). Calore, the main tributary of the Volturno river, and Candelaro are the main rivers flowing respectively in the western and eastern parts of the study area (Fig. 2). Calore covers 3 058 km2 and about 500 km of hydrographic network (river flow: 32 m3 s-1). The Calore river is known to host otters only in the upper part, and only occasional signs have been recorded in the middle stretches downstream of the city of Benevento (Loy et al., 2015; Scorpio et al., 2016). The Candelaro water basin covers an area of 2 560 km2 and 350 km of hydrographic network (river flow: 2.5 m3 s-1). Additionally, we investigated the Lesina and Varano coastal lakes (51 km2 and 60 km2) respectively, where the species has not been detected since the 1990s (Cassola, 1986; Reggiani and Ciucci, 1994; Marrese and Caldarella, 2005). A total of 94 sites were surveyed in 36 Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) squares: 19 sites in the western Tyrrhenian, and 75 in eastern Adriatic side of the Apennine watershed. Following the standard procedure recommended by Reuther et al. (2000) up to four sites were surveyed for each 10 x 10 km UTM grid cell of the study area. We didn’t survey UTM squares where otter signs were found in the last three years by other studies (Loy et al., 2015; Scorpio et al., 2016). In order to optimize the survey efforts, sites were checked preferably starting from bridges, well vegetated river banks, or pools. We avoided those sites located on headwaters, low order streams (Strahler, 1974), or on dry watercourses. Where dense reedbeds along channel banks prevented the search for marking sites, signs were only searched for under bridges. Rivers were checked for otter signs, especially spraints, along at least 600 m of one bank (Reuther et al., 2000). As soon as a reliable otter sign was found, the transect line was stopped; only when otter signs were found immediately at the beginning of the transect we checked the first 100 metres of the river in order to investigate the prevalent environmental characteristics. The survey was carried out between March and May 2017 avoiding periods of heavy rainfalls in the previous week (Fusillo et al., 2007; Imperi, 2013).

RESULTS

All squares on the western side of the study area were positive for otter presence (Fig. 2). Otter signs were found at 22 sites out of 94 (23%). However, a large difference in relative proportion of positive vs negative sites was observed in the Tyrrhenian (22 out of 27 = 81,4%) vs the Adriatic (5 out of 67 = 7,4%) side. Otters were found in all stretches of Calore River and its tributaries: Tammaro, Miscano, Ufita, Fredane, and Sabato. In 65% of sites of this area, signs were found in the first 100 m of the transect. Moreover, despite the short length of the stretches surveyed (i.e. < 100 m) on some rivers (i.e. Ienga creek, Ufita and Fredane rivers) we found high densities of marking sites (Fig. 3). Otter were also found in the Sabato River, downstream of the densely populated city of Avellino, inside an industrial area and close to a hydroelectric power station (Fig. 4).

(click for larger version)

On the Adriatic side only four sites were positive for the presence of otters, and one was doubtful (Fig. 2). All positive sites were found in the Candelaro river basin, along the Salsola and Vulgano creeks, where a latrine was found in front of a waste water outfall in the suburbs of the city of Lucera (Fig. 4). The riverine vegetation belt of the Candelaro river was narrow (less than 10 m wide) and mainly composed of reedbeds often destroyed by cutting. However, the freshwater fauna of the lower part of the river appeared quite rich.

(click for larger version)

DISCUSSION

Our results revealed that the gap area between the two portions of the otter range in southern Italy has been filled up, and the species now occurs in one continuous range from Abruzzo to Calabria and Puglia (Fig. 5). Compared with results of surveys conducted in the last decade within the Tyrrhenian side of the gap area (De Castro et al., 2013; Loy et al., 2015; Scorpio et al., 2016), all river stretches previously found to be negative are now positive. This widespread occurrence, the high density of marking sites and the occurrences in suboptimal patches around large cities suggest that on the Tyrrhenian side otters have likely reached the carrying capacity (Fretwell, 1972) of the gap area. These outcomes encourage future surveys in the neighbouring rivers in the Latium region that were recently found still avoided of otters (Giovacchini and Loy pers. obs.).

(click for larger version)

Conversely, otters are still rare in the Adriatic side of the gap area, concentrated in the Candelaro river basin and clustered in small tributaries. Interestingly, they occur in suboptimal patches and are absent from pristine riverine habitats and high water quality water courses like the San Lorenzo and Celone creeks (ARPA Puglia, 2015). These creeks run into the Celone reservoir, and during the survey period there was no water downstream of the dam. As usually dams do not prevent movements of otters and reservoirs could rather increase survival during periods of drought (Basto et al., 2011; Pedroso et al., 2007, 2014) it is rather the absence of water downstream that might have prevented otters from colonizing the pristine upstream stretches of these creeks. Signs of otter found during opportunistic searching in shallow marshes near the mouth of Candelaro river (Marrese, pers. obs.) suggest that otters arrived from the southern Cervaro river basin, by moving through a drainage channel connecting both river basins, as other signs were previously found along this water body (Marrese, pers. obs.). As the fish community seems to be quite rich, it is possible that the otter expansion in this water basin is just starting, and future surveys could likely witness a further increase of positive signs.

Despite otters being sighted in the past in both Lesina and Varano lakes (Marrese and Caldarella, 2005), only a very old spraint was found on an artificial heap of rocks in the Varano lake (maybe a shag (Phalacrocorax aristotelis) pellet: Dell’Omo, pers. com.), and none in the Lesina lake. Although numerous fish nets and fish traps suggested good availability of feeding resources, the water quality is classified as ‘Poor’ for the Lesina lake, and ‘Moderate’ for the Varano (ARPA Puglia, 2015). The evidence suggest that the lakes could be frequented only by wandering individuals. However, survey of the lakes may have also suffered from a low detection probability, as most areas were not accessible to survey (soft muddy shores, artificial channels and private properties).

CONCLUSION

The new occurrence records collected during this study indicate that the Italian otter population has been reunified in one single continuous EOO (sensu IUCN, 2012). The gap filling between the two portions of the southern Italian range is likely related to improving habitat quality during the last 20 years, e.g. higher water quality, natural recovery of riverbank vegetation (Carone et al., 2014), and lower human impact on streams (Marcelli and Fusillo, 2009b). The rejoining has several implications on the conservation and management of the Eurasian otter in Italy:

- it guarantees gene flow across the whole southern range;

- it promotes the metapopulation dynamics and diminishes the risk of extinction of sub populations (Christie and Knowles, 2015), especially in the small northern portion, safeguarding the ongoing northward expansion (Panzacchi et al., 2011; Imperi, 2013).

Otters have likely reached carrying capacity in the Tyrrhenian portion of the gap area, making a further expansion northward in the near future highly probable, especially in the neighbouring Lazio region, which is still devoid of otters (Giovacchini and Loy, pers. obs.).

In contrast, the low amount of positive sites in the eastern part of the gap area highlights the need for a habitat survey along the Candelaro river, and the promotion of functional connections with the neighbouring Cervaro and Fortore river basins. Finally, it is advisable to monitor the Lesina and Varano lagoons, and to investigate potential conflicts with fishermen and fish farmers in the whole study area for a rapid activation of mitigation measures and to raise public awareness on this valuable flagship top predator of freshwater ecosystems.

Acknowledgements: The study was funded by the National Park of Cilento, Vallo di Diano and Alburni in the framework of a research agreement with the Università degli Studi del Molise on “Conservazione della lontra”. We are grateful to Anita Botticelli for logistic support, Antonio Giovacchini for helping in the fieldwork, and to Daniele Valfré for making available his literature references.

REFERENCES

Agapito Ludovici, A., Cecere, F., Marchetti, F., Visceglia, M. (1994). Nuovi dati sulla presenza della lontra in Basilicata. Studi e Ricerche Sist. Aree Prot. WWF It. 2: 77-79. [in Italian]

ARPA Puglia (2015). Proposta di classificazione dei Corpi Idrici Superficiali nella regione Puglia: analisi integrata a chiusura del primo ciclo triennale di monitoraggio ai sensi del DM 210/2010. ARPA, Servizio di monitoraggio dei corpi idrici superficiali. [in Italian]

Balestrieri, A., Remonti, L., Prigioni, C. (2016). Toward extinction and back: decline and recovery of otter populations in Italy. In: Angelici, F.M. (Eds.). Problematic wildlife: a cross-disciplinary approach. Springer International Publishing, pp. 91-105.

Basto, M.P., Pedroso, N.M., Mira, A., Santos-Reis, M. (2011). Use of small and medium-sized water reservoirs by otters in a Mediterranean ecosystem. Animal Biology 61 (1): 75-94.

Beseghi, A., Donati M. (1987). La Lontra Lutra lutra L., nelle province di Parma e Reggio Emilia. Atti Soc. Ital. Sci. nat. Museo civ. Stor. nat. Milano 128: 67-79.

Bonelli, G., Moltoni, E. (1929). Selvaggina e caccie in Italia. Comitato ornitologico venatorio, R. Istituto Superiore di Medicina Veterinaria. [in Italian]

Cagnolaro, L., Rosso, D., Spagnesi, M., Venturi, B. (1975). Inchiesta sulla distribuzione di lontra (Lutra lutra) in Italia e nei Cantoni Ticino e Grigioni (Svizzera). 1971-1973. Ric. Biol. Selv. 63, 120 pp. [in Italian]

Carone, T., Guisan, A., Loy, A., Carranza, M.L. (2014). A multi-temporal approach to model endangered species distribution in Europe. The case of the Eurasian otter in Italy. Ecological modelling 274: 21-28.

Cassola, F. (1986). La lontra in Italia. Censimento, distribuzione e problemi di conservazione di una specie minacciata. WWF Italia, Serie Atti e Studi 5. [in Italian]

Cavazza, F. (1911). Dei Mustelidi Italiani. Ann. Mus. Civ. St. Nat. Genova 5: 170-204.

Christie M.R., Knowles L.L.(2015). Habitat corridors facilitate genetic resilience irrespective of species dispersal abilities or population sizes. Evolutionary Applications 8(5): 454-463.

Crawford, A. (2003). Fourth otter survey of England, 2000-2002. Environment Agency, 2003.

De Castro, G., Loy, A. (2007). Un nuovo censimento della lontra (Lutra lutra, Carnivora, Mammalia) nel fiume Sangro (Abruzzo): inizia la ricolonizzazione dell’Italia centrale? 68° convegno dell’Unione Zoologica Italiana, Lecce, 24-27 settembre 2007. Riassunti: 105. [in Italian]

De Castro, G., Lerone, L., Imperi, F., Loy, A. (2013). Dams and natural expansion of the otter. Barriers or resources? The case of two river basins in central Italy. Book of abstracts of the 31st Mustelid Colloquium, 25-26 October 2013, Szczecin (Poland).

Fretwell, J. (1972). Population in a seasonal environment. Princetown University Press, Princetown.

Fusillo, R., Marcelli, M., Boitani, L. (2007). Survey of an otter Lutra lutra population in southern Italy: site occupancy and influence of sampling season on species detection. Acta Theriologica 52 (3): 251-260.

Giglioli, E.H. (1880). Elenco dei Mammiferi, degli Uccelli e dei Rettili ittiofagi appartenenti alla fauna italiana e catalogo degli Anfibi e Pesci italiani inviati alla Esposizione Internazionale di Pesca di Berlino. Cat. Gen. Esp. intern. Pesca, Sez. It. 11: 63-117. [in Italian]

Ghigi, A. (1911). Ricerche faunistiche e sistematiche sui Mammiferi d’Italia che formano oggetto di caccia. Natura 2: 289-337. [in Italian]

Imperi, F. (2013). Monitoraggio e dinamica dell’areale della lontra (Lutra lutra, Carnivora, Mammalia) nel bacino del fiume Sangro. Tesi di laurea. Sapienza Università di Roma. [in Italian]

IUCN (2012). IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria: Version 3.1. Second edition. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

Janssens, X., Defourny, P., De Kermabon, J., Baret, P. (2006). The recovery of the otter in the Cevennes (France): a GIS-based model.Hystrix-the Italian Journal of Mammalogy, 17(1): 5-14.

Loy, A, Bucci, L, Carranza, ML, De Castro, G, Di Marzio,P and Reggiani, G (2004). Survey and habitat evaluation for a peripheral population of the Eurasian otter in Italy.IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin, 21A

Loy, A., Boitani, L., Bonesi, L., Canu, A., Di Croce, A., Fiorentino, P. L., Genovesi, P., Mattei, L., Panzacchi, M., Prigioni, C., Randi, E., Reggiani, G. (2010). The Italian action plan for the endangered Eurasian otter Lutra lutra. Hystrix It. J. Mamm. (n.s.) 21(1), 19-33.

Loy, A., Balestrieri, A., Bartolomei, R., Bonesi, L., Caldarella, M., De Castro, G., Della Salda, L., Fulco, E., Fusillo, R., Gariano, P., Imperi, F., Iordan, F., Lapini, L., Lerone, L., Marcelli, M., Marrese, M., Pavanello, M., Prigioni, C., Righetti, D. (2015).The Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) in Italy: distribution, trend and threats. IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 32 C: Proceedings European Otter Workshop, 8 - 11 June 2015, Stockholm, Sweden.

Macdonald, S.M., Mason, C.F. (1983). The otter Lutra lutra in Southern Italy. Biological Conservation 25: 95-101.

Marcelli, M. (2006). Struttura spaziale e determinanti ecologici della distribuzione della lontra (Lutra lutra) in Italia. Sviluppo di modelli predittivi per l’inferenza ecologica e la conservazione. Tesi di dottorato. Università di Roma “La Sapienza”, 108 pp. [in Italian]

Marcelli, M., Fusillo, R. (2009a). Monitoring peripheral populations of the eurasian otters (Lutra lutra) in southern Italy: new occurrences in the Sila National Park. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 26 (1).

Marcelli, M., Fusillo, R. (2009b). Assessing range re-expansion and recolonization of human-impacted landscapes by threatened species: a case study of the otter (Lutra lutra) in Italy. Biodiversity Conservation 18: 2941-2959.

Marrese, M., Caldarella, M. (2005). Survey of Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra) in Apulia region south-east of Italy. >Proceedings of European Otter Workshop, Certosa di Padula, Salerno.

Marrese, M., Caldarella, M., Gioiosa, M., Silvestri, F., Martino, L., Costantino, G., Ungaro, N., Petruzzelli, R. (2014). Monitoraggio e aggiornamento della presenza della lontra eurasiatica Lutra lutra in Puglia. Atti Congresso Nazionale di Teriologia, Hystrix 25, Civitella Alfedena. [in Italian]

Mattei, L., Antonucci, A., Antonelli, F. (2001). Rilascio sperimentale della Lontra nel Parco Nazionale della Majella. III Convegno SMAMP. La Lontra in Italia: distribuzione, censimento e tutela. Montella 30 novembre-2 dicembre 2001. Dryocopus IV, 2001.

Panzacchi, M., Genovesi, P., Loy, A. (2011). Piano d’Azione Nazionale per la Conservazione della Lontra (Lutra lutra). Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio - ISPRA. [in Italian]

Pavan, G., Mazzoldi, P. (1983). Banca dati della distibuzione geografica di 22 specie di Mammiferi in Italia. Collana Verde 66: 33-279, Ministero Agricoltura e Foreste. [in Italian]

Pavanello, M., Lapini, L., Kranz, A., Iordan, F. (2015). Rediscovering the Eurasion Otter (Lutra lutra) in Friuli Venezia Giulia and notes of its possible expansion in northern Italy. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 32 (1): 12-20.

Pedroso, N.M., Sales-Luís, T., Santos-Reis, M. (2007). Use of Aguieira dam by Eurasian otters in Central Portugal. Folia Zoologica 56 (4), 365-377.

Pedroso, N.M., Marques, T.A., Santos-Reis, M. (2014). The response of otters to environmental changes imposed by the construction of large dams. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 24 (1), 66-80.

Prigioni, C., Pandolfi, M., Grimod, I., Fumagalli, R., Santolini, R., Arcà, G., Reggiani, G., Montemurro, F., Bonacoscia, M., Racana, A. (1989). Progetto Lontra Italia. Prima fase. Relazione Tecnica per il Ministero dell'Ambiente, 168 pp. [in Italian]

Prigioni, C., Remonti, L., Balestrieri, A., Sgrosso, S., Priore, G., Misin, C., Viapiana, M., Spada, S., Anania, R. (2005). Distribution and sprainting activity of the otter (Lutra lutra) in the Pollino National Park (Southern Italy). Ethology, Ecology and Evolution 17: 171-180.

Reggiani, G., Ciucci, P. (1994). Indagine sulla presenza di specie ed habitat di interesse comunitario nei Parchi dell’Italia meridionale (Cilento-Vallo di Diano, Pollino e Gargano). Gruppo Mammalofauna, Carnivori: Lupo, Lontra e Foca Monaca. Rapporto tecnico non pubblicato. Istituto di Ecologia Applicata, Roma, 48 pp. [in Italian]

Reggiani, G., Raganella Pelliccioni, E., Bianco, P., Barbagli, R. (1995). Studio sull’ittiofauna, la Lontra e l’ambiente acquatico nelle Valli del Farma e del Merse. Rapporto tecnico per l’Amministrazione Provinciale di Siena, Istituto di Ecologia Applicata, Roma, p. 100. [in Italian]

Reggiani, G., Pittiglio, C., Zini, R., Boitani, L. (2001). Progetto Lontra Grosseto. Rapporto finale per l’Amministrazione Provinciale di Grosseto, giugno 2001. [in Italian]

Regione Molise (2016). Piano di tutela delle acque (Art. 121 D.Lgs 152/2006 e ss.mm.ii.). Monografie dei corpi idrici e delle pressioni antropiche. Documento predisposto a cura del Gruppo di Lavoro ARPA Molise - Regione Molise. [in Italian]

Reuther, C., Dolch, D., Green, R., Jahrl, J., Jefferies, D., Krekemeyer, A., Kucerova, M., Bo Madsen, A., Romanowsky, J., Roche, K., Ruiz-Olmo, J., Teubner, J., Trinidade, A. (2000). Surveying and monitoring distribution and population trends of the Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra): guidelines and evaluation of the standard method for surveys as recommended by the European Section of the IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group. Habitat 12: 1-148.

Rondinini, C., Battistoni, A., Peronace, V., Teofili, C. (2013). Lista Rossa IUCN dei Vertebrati Italiani. Comitato Italiano IUCN e Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare. [in Italian]

Ruiz-Olmo, J., Delibes, M. (1998). La nutria en Espana ante el orizonte del ano 2000. SECEM, Malaga.

Ruiz-Olmo, J., Lafontaine, L., Prigioni, C., López-Martín, J.M., Santos-Reis, M. (2000). Pollution and its effects on otter populations in south-western Europe. In Conroy, J.W.H., Yoxon, P., Gutleb, A.C (Eds.). Proceedings of the First Otter Toxicology Conference, Journal of the International Otter Survival Fund, pp. 63-82.

Scorpio, V., Loy, A., Di Febbraro, M., Rizzo, A., Aucelli, P. (2016). Hydromorphology meets mammal ecology: river morphological quality, recent channel adjustment and otter resilience. River Research and Applications 32 (3): 267-279.

Spagnesi, M., Cagnolaro, L. (1981). Lontra Lutra lutra Linnaeus, 1758. In: CFS delle Regioni Autonome, Istituto di Entomologia dell’Università di Pavia (Eds.). Distribuzione e biologia di 22 specie di Mammiferi in Italia, CNR, Roma, pp. 95-101. [in Italian]

Strahler, A.N. (1974). Geografia fisica. Omega, Barcelona. [in Italian]

Wayre, P. (1976). Attuale situazione della lontra in Italia e proposte per la sua conservazione. Contributi scientifici alla conoscenza del Parco Nazionale d’Abruzzo 13. [in Italian]

Resumé: Bonnes Nouvelles du Sud: Remplissage du Gap entre Deux Populations de Loutre en Italie

Après le déclin important de la deuxième partie du XXe siècle en Italie, la loutre (Lutra lutra) a été confinée dans la partie sud de la péninsule. Depuis les relevés effectués dans les années 80, la zone d'occurrence de cette espèce a subi une expansion lente mais constante, tout en maintenant deux populations disjointes. Le remplissage de ce gap est un des objectif du plan d’action nationale publié en 2011. Pour évaluer la réalisation de cet objectif nous avons réalisé une etude systématique dans la zone de connexion, à la recherche de signes dans deux bassins fluviaux et deux lacs des Pouilles et de la Campanie. Signes des loutres ont été détectées le long de la plus grande partie du réseau hydrographique étudié, ce qui confirme le comblement des lacunes entre les deux aires de répartition, qui sont maintenant reliées en une seule zone d'occurrence. Cette réalisation a des résultats pertinents sur la survie à long terme de la petite population menace de loutres italiennes

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Buenas Noticias del Sur: Llenando la Brecha entre dos Poblaciones de Nutria en Italia

Después del severo declive ocurrido durante la segunda parte del siglo 20 en Italia, la nutria (Lutra lutra) estaba confinada en la parte sur de la península, con dos núcleos aislados. De manera similar a otras poblaciones europeas, en los 90s comenzó una lenta recuperación de las mismas. Llenar la brecha entre las dos subpoblaciones fue uno de los principales objetivos del plan de acción italiano lanzado en 2011. Para evaluar el logro de este objetivo, realizamos en 2017 un relevamiento sistemático en el área de conexión, en busca de señales de nutrias en dos cuencas fluviales y dos lagos de las porciones Tirrena (Campania) y Adriática (Puglia) del área de la brecha. Se detectaron nutrias a lo largo de la mayoría de la red hidrográfica estudiada en el lado Tirreno, y sólo unos pocos sitios en el lado Adriático. Los resultados confirmaron el relleno de la brecha entre las dos áreas de distribución inconexas, y resaltan la necesidad de un relevamiento de los hábitats en los cursos de agua Adriáticos. Estos resultados tienen implicancias para la supervivencia a largo plazo de la pequeña y amenazada población de nutrias en Italia.

Vuelva a la tapa