IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Volume 35 Issue 4 (December 2018)

Citation: Pinillosa, L, Pérez-Torres, J and Botero-Botero, A (2018). Diet of Lontra longicaudis in Espejo River, Quindío, Colombia. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 35 (4): 222 - 229

Diet of Lontra longicaudis in Espejo River, Quindío, Colombia

Laura Pinillosa1*, Jairo Pérez-Torres2* and Alvaro Botero-Botero3

1 Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia, Cl. 74#11-81, Bogotá, Colombia

2Laboratorio de Ecología Funcional, Unidad de Ecología y Sistemática (UNESIS), Depto. Biología, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Cr. 7 # 43-82, Bogotá, Colombia

3Grupo de investigación en Biodiversidad y Educación Ambiental -BIOEDUQ-, Universidad del Quindío, Armenia, Colombia

* Corresponding Author: Email: jaiperez@javeriana.edu.co

Received 16th February 2018, accepted 21st August 2018

Abstract: We studied the diet of the Neotropical otter, Lontra longicaudis in the Espejo River (Department of Quindío, Colombia). This river has the highest levels of pollution within the catchment area of the La Vieja River. We visited a 5.6 km section of the river on nine occasions during the month of July 2009 and collected 131 otter scats. The fecal samples were washed, sieved, and their contents were examined. Stool samples indicated that the otter’s diet in this river is mainly composed of fish comprising seven predated species. The most common prey items were Hypostomus sp. (31.6% of samples) and Brycon henni (29.22% of samples).

Keywords: anthropic disturbances, carnivore, foraging, environmental pollution.

INTRODUCTION

The Neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis is a key predator in tropical aquatic environments, and the species occupies the highest level of the food chain (Gallo-Reynoso et al., 2008) and plays a regulatory role in the food web in aquatic systems (Waldemarin, 2004). Although there have been studies on this otter in the coffee-growing ecoregion of Colombia (Botero-Botero and Torres-Mejia, 2007; Mayor-Victoria and Botero-Botero, 2010a; Mayor-Victoria and Botero-Botero, 2010b; Restrepo and Botero-Botero, 2012), information for the Espejo River on its natural history needs to be collected.

This species is in danger of local extinction due to a series of anthropogenic factors (Botero-Botero and Torres-Mejia, 2007). Although it has been reported that the otter tolerates water pollution, the Espejo River is one of the most polluted in the basin of the La Vieja River due to discharges of industrial and urban wastewater, along with local agricultural and livestock activities (Botero-Botero and Torres-Mejía, 2007; Londoño et al., 2007). This can affect the otter due to the loss of food resources and the deterioration of riparian habitats where it finds refuge.

Here we present a description of the diet of the Neotropical otter in the Espejo River (department of Quindío, Colombia) that can serve as baseline information for the protection of the food resources of this species in the study area.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Area

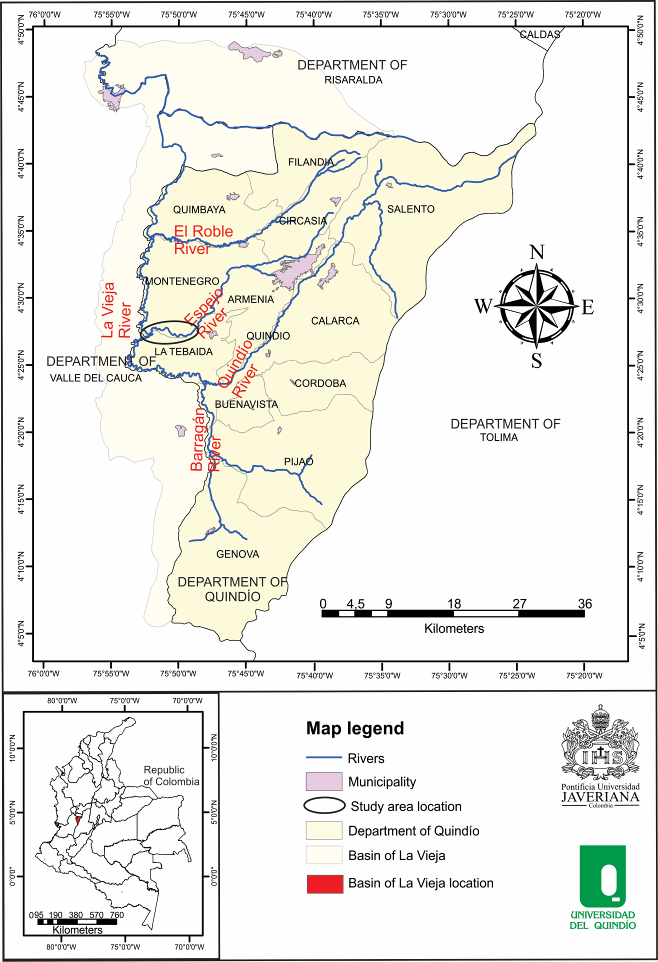

The Espejo River is located to the northeast of the department of Quindío, Colombia (Fig. 1). The river starts at an altitude of 1300 m at the bridge of Pantanillo (municipality of Montenegro) and flows into the La Vieja River, west of the municipality of La Tebaida. It is a tertiary class river of 40.1 km in length with a catchment area of 159 km2 and is fed by a large number of tributaries including La Coqueta, La Blanquita, El Vadeo and Anapoima, among others.

The river begins at the union of two streams: Hojas Anchas and Armenia. The Espejo River originally was a river of clean and crystalline waters but nowadays it contains high levels of organic contamination from wastewater from both urban and industrial sources. The pollution of the river is mainly due to the lack of enforcement and paucity of legal regulations on the quality of waters discharged into it (Londoño et al., 2007). The sector most affected by pollution is the central section, where the Armenia stream brings water from the municipality of the same name. From this point and downstream the color of the water changes, oxygen levels fall, the biochemical and chemical oxygen demand increase (BOD and COD), and turbidity levels are high (Londoño et al., 2007).

During our study, we observed that, although the river had an important degree of pollution, the riparian vegetation was well preserved. However, overall these changes represent an important decrease in the quality of the habitat and food resources for the otter.

We froze the samples until required for processing. In the laboratory, we separated each sample and gently washed it with water and liquid soap in a 2.4-micron sieve. We dried the food items found in each sample in a convection oven (Cole Parmer® Model 05015-58) at 250 °C and separated the identifiable fragments of the diet by food categories, dividing them into fish, mammals, birds, seeds, hairs, gastropods, larvae and plant remains.

Data Collection

During July 2009, we walked nine 5.6 km lengths along the lower section of the river. During each trip, we surveyed the area by searching for spraints (otter scats). When otter scats were located, we collected each one and stored it in a plastic zipper bag and labeled it with the following data: GPS coordinates, altitude (meters above sea level), time, date, collector’s name, level of desiccation, and the number of spraints found at each point.

We froze the samples until required for processing. In the laboratory, we separated each sample and gently washed it with water and liquid soap in a 2.4-micron sieve. We dried the food items found in each sample in a convection oven (Cole Parmer® Model 05015-58) at 250 °C and separated the identifiable fragments of the diet by food categories, dividing them into fish, mammals, birds, seeds, hairs, gastropods, larvae and plant remains.

The vertebrae and scales of the different fish were identified with the help of the fish guide for the region (Mayor-Victoria 2008).. The relative frequency of occurrence of each food item (FR) was calculated using the formula: FR= (ni/n).100, where: ni= number of fecal samples with the food item i and n= total fecal samples found (Anderson et al., 2008). We classified the items consumed by otters as constant items (FR>50%) accessory items (FR= 25-50%), or accidental items (FR< 25%), following the classification of Biffi and Iannacone (2010). We calculated the proportion of occurrence of each prey item in the samples using the formula: PA=fi/F.100 where: fi is the number of spraints in which species i appeared and F is the total number of occurrences of all prey types in all the droppings, and we calculated the total items by adding all the fi values (Casariego-Madorell et al., 2008).

RESULTS

The Espejo River otters showed evidence of a wide spectrum of food items. Fish predation dominated both in the number of species predated (S=7), and the percentage of their occurrence in stool samples (PA=69.1). These were followed by mammals (PA=6.2), birds (PA=3.7); and finally, other items such as seeds, gastropods, invertebrate larvae, insects and hairs that were pooled and considered in a single group (PA=2.7) (Table 1).

Otters showed a clear tendency to consume fish of the family Loricariidae, especially the specie Hypostomus niceforoi (FR=31.60; PA=22.6, classified as a constant dietary item), and the genus Ancistrus (FR=20.40; PA=14.5; classified as an accessory item). Consumption of fishes in the family Characidae was found to mainly involve medium-sized species, such as Sabaleta (Brycon henni, FR=29.22; PA=20.1; classified as a constant dietary item), and to a lesser proportion small fish such as Astyanax sp. (accidental prey) and Lebiasina sp. (accidental prey). Finally, the family Heptateridae was represented by the genus Rhamdia (accidental item) (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

The diet and distribution of the Neotropical otter populations are likely related to the ecological and behavioral habits of the fish species that form a major part of their diet (Lopes et al., 2012). This underlines the need to characterize species richness and abundance of the ichthyofauna in the area of study to determine the probability of each of these species being available as potential prey for the otter. In this way, it may be possible to understand the relationship between the different ecological and biological aspects of the fish species (e.g., habits, seasonal patterns, reproduction seasons, among others), with the prey selection behavior of the otters. This topic merits future research (Lopes et al., 2012).

Although many medium-sized predators consume a wide variety of resources, they generally prefer items based on their abundance, energy search costs and consumption risks (Begon et al., 2006). The preference for an item is reflected in the percentage of its prevalence in the diet; this reflects its use more than the percentage of occurrence in the environment (Begon et al., 2006).

Otters in the Espejo River mainly consume particular types of fish, as observed in previous studies in Colombia and elsewhere in Latin America (Macias-Sánchez and Aranda, 1999; Quadros and Monteiro-Filho, 2001; Gori et al., 2003; Kasper et al., 2004; Kruuk, 2006; Rosales, 2009; Mayor-Victoria and Botero-Botero, 2010a; Restrepo and Botero-Botero, 2012). The otter population in this river had a high tendency to prey on fish of the family Loricariidae, within which the species Hypostomus nicefori was the most frequently consumed. In the Espejo River the only species of Hypostomus present is Hypostomus nicefori, listed as a species introduced into the basin of the La Vieja River (com. pers. D. Taphorn). If the otters consume the prey according to their availability, it is probable that the remains found in the feces belong to this species. This suggests that the Neotropical otter acts as a biological controller of this introduced species as it is its main food source.

The fish of Hypostomus shelter among tree roots and rocks in the water (Garavello and Garavello, 2004), and are easy prey for the otter. The slow movement and bentophage (bottom-feeding) habits of species within this genus facilitate their capture by the otter. These habits probably also imply lower energy expenditure in the process of pursuit and capture (Quadros and Monteiro-Filho, 2001; González et al., 2004; Mayor-Victoria and Botero-Botero, 2010a). This also explains the high occurrence of species in the genera Ancistus and Chaetostoma from the family Loricariidae, in which similar findings on the selection of slowmoving prey items were reported for otters in the La Vieja River (Restrepo and Botero-Botero, 2012), and the Roble River (Mayor-Victoria and Botero-Botero, 2010a; Lopes et al., 2012). These authors consider that L. longicudis engages in generalist and opportunistic feeding behavior, which favors the consumption of slow-moving prey, regardless of their size.

The fish species Brycon henni (Characidae) also occurred in scats samples at high frequencies. Fishes of this genus are characterized by their large sizes in Andean ecosystems, with individuals that exceed 115mm in length (Zuluaga-Gomez et al., 2014) and for their abundance in this region (García-Alzate et al., 2009; Botero-Botero and Ramírez-Castro, 2011). This would likely improve their detection by otters, for which they may represent valuable food resources that provide attractive returns on the energetic investment in the pursuit and capture of this type of prey. The presence of fish items of the genus Rhamdia (Heptapteridae) that are small fast-moving fishes with nocturnal habits such as Astyanax faciatus and Lebiasina sp. may reflect opportunistic predation events by the otters.

The presence of B. henni in the diet of the otter may explain the occurrence of several of the items detected in the food category of "others" (Table 1). In fact, these fishes can consume seeds and fruits as well as insect larvae, adult insects and small gastropods (Botero-Botero and Ramírez-Castro, 2011). The presence of seeds in the otter scat can be attributed to the fact that they form part of the diet of some fish consumed by the otters, and for this reason we do not consider them part of the diet.

A number of items classified as mammalian may correspond with small rodents related with bodies of water, as indicated by the type of hair registered in stool samples. However, the reference collection that we use does not allow us to obtain more precise mammal identifications; we need to improve the hair collection of small mammals in the area.

Although present at a very low proportion, we detected the consumption of birds in scat samples and we classified this as accidental. Although the consumption of birds by the otters has already been reported in other countries (Larivière, 1999), this constitute the first evidence for the consumption of birds by the Neotropical otter in Colombia. Gallo-Reynoso et al. (2008) reported the consumption of birds in the diet of L. longicaudis, mostly involving aquatic avian species. Similarly, Quadros and Monteiro-Filho (2001) reported that otters ate birds associated with the otter's habitat, underlining that the neotropical otter is a species with opportunistic feeding habits.

Despite its classification as accidental, we should investigate the importance of birds in the otter diet throughout its range in Colombia. Due to the elevated pollution levels on some rivers where they live, it is possible that the relative frequency of consumption of birds could increase relative to a decrease in the preferred fish resources due to river pollution.

As Botello says, (2004) in an evaluation on the state of the Neotropical otter in the Cauca river, “Factors such as the deterioration of riparian vegetation and alteration of water quality negatively influence the density of otter populations”. Because the Espejo River contains high levels of contamination from domestic, industrial and agricultural origins (Londoño et al., 2007), we believe that Neotropical otters in this river are at risk of decreasing. Thus, we propose the establishment of a monitoring program for both otters and their prey.

In comparison with other studies (that had longer sampling periods) we found a high number of spraints. This could be due to the high density of otters, or to the fact that a few otters are showing high activity (searching for food or marking territory). Our data and the sampling used in this study does not allow for an evaluation of these options, and we suggest a population analysis in later studies.

Despite being more abundant at sites with low human presence, the Neotropical otter quickly adapts to environmental changes (Larivière, 1999). Also, the behavior of Neotropical otter normally is diurnal in areas with low human access, but behavior becomes nocturnal in areas with a high degree of human disturbance (Lariviére, 1999). The otter is abundant in places with low human presence and quickly adapts to environmental changes (Larivière, 1999), the fact that the Espejo River has a significant degree of pollution and the riparian vegetation is well-preserved could favor the otter, since this vegetation could be a refuge for potential prey of the otter.

Acknowledgements: The authors gratefully acknowledge the Laboratory of Functional Ecology, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation through the Colombia Program at WCS, and the Neotropica-Colombia foundation for providing equipment. We also thank Carlos A. Restrepo, Guillermo A. Cardenas and John D. Garcia for collaboration in fieldwork and Trevor Williams (INECOL, México) for his comments.

REFERENCES

Anderson, D.R., Sweeney, D.J., Williams, T.A. (2008). Estadística para Administración y Economía. Cengage Learning Editores, S.A., México. 1056 pp. [in Spanish]

Begon, M., Townsend, C.R., Harper, J.L. (2006). Ecology: From individuals to Ecosystems. Fourth edition. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, England. 750 pp.

Botello, J.C. (2004). Evaluación del estado de la nutria de río Lontra longicaudis (Olfers, 1818) en el río Cauca, zona de influencia del municipio de Cali – Departamento del Valle del Cauca. CVC. Fundación Natura Colombia. 44 pp. [in Spanish]

Botero-Botero, A., Ramírez-Castro, H.M. (2011). Ecología trofica de la Sabaleta Brycon henni (Pisces: Characidae) en el río Portugal de Piedras, Alto Cauca, Colombia. Rev. MVZ Córdoba, 16 (1): 2349-2355. [in Spanish]

Botero-Botero, A., Torres-Mejía, A.M. (2007). Distribución y abundancia relativa de Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora, Mustelidae) en la cuenca del río La Vieja, Alto Cauca, Colombia. Informe presentado a la Fundación Ecoandina/WCS Colombia, Cali. [in Spanish]

Casariego-Madorell, M.A., List, R., Ceballos, G. (2008). Tamaño poblacional y alimentación de la nutria de río (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en la costa de Oaxaca, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (n.s.), 24 (2): 179-200. [in Spanish]

Gallo–Reynoso, J.P., Ramos–Rosas, N.N., Rangel-Aguilar, O. (2008). Depredación de aves acuáticas por la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en el río Yaqui, Sonora, México. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 79: 275-279. [in Spanish]

Garavello, J.C., Garavello, J.P. (2004). Spatial distribution and interaction of four species of the catfish genus Hypostomus Lacépède with bottom of rio São Francisco, Canindé do São Francisco, Sergipe, Brazil (Pisces, Loricariidae, Hypostominae). Braz. J. Biol. 64 (3B): 591-598.

García-Alzate, R., García, C., Botero-Botero, A. (2009). Composición, estacionalidad y hábitat de los peces de la quebrada Cristales, afluente del río La Vieja, Alto Cauca, Colombia. Revista de Investigaciones Universidad del Quindío, 19: 115-121. [in Spanish]

González, I., Utrera, A., Castillo, O. (2004). Dieta de la nutria Lontra longicaudis en el río Ospino, estado Portuguesa, Venezuela. En: Puertas P., Verdi, L. (Eds.). Libro de resúmenes del VI congreso internacional de manejo de fauna silvestre en la Amazonía y Latinoamérica. Universidad Nacional de la Amazonía Peruana (UNAP), Iquitos. [in Spanish]

Gori, M., Carpaneto, G.M., Ottino, P. (2003). Spatial distribution and diet of the neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis in the Ibera Lake (northern Argentina). Acta Theriol. 48: 495-504.

Kasper, C.B., Feldens, M.J., Salvi J.A., Grillo, H.C. (2004). Estudo preliminar sobre a ecología de Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora, Mustelidae) no Vale do Taquaria, sul do Brasil. Rev. Bras. Zool. 21 (1): 61-72. [in Portuguese]

Kruuk, H. (2006). Otters: Ecology, Behavior and Conservation. Oxford University Press, England.

Larivière, S. (1999). Lontra longicaudis. Mammalian Species, 609: 1-5.

Londoño, A., Rojas, A., Gomez, A., Torres, D. (2007). Determinación de la residualidad de plaguicidas organoclorados y organofosforados por cromatografía de gases, variación en los parámetros fisicoquímicos e identificación de macroinvertebrados bentónicos en el río Espejo del departamento del Quindío como indicadores de la calidad del agua. Revista de la Asociación Colombiana de Ciencias Biológicas, 19 (1): 82- 93. [in Spanish]

Lopes, R.M., Oliveira-Santos, L.G., Caramaschi, E.P., Waldemarin, H.F. (2012). Are otter’s generalists or do they prefer larger, slower prey? Feeding flexibility of the Neotropical Otter Lontra longicaudis in the atlantic forest. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 29 (2): 80-94.

Macias-Sánchez, S., Aranda, M. (1999). Análisis de la alimentación de la nutria Lontra longicaudis (Mammalia: Carnivora) en un sector del río Los Pescados, Veracruz, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (n.s.) 76: 49-57. [in Spanish]

Mayor-Victoria, R., Botero-Botero, A. (2010a). Dieta de la nutria neotropical Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora: Mustelidae) en el río Roble, alto Cauca, Colombia. Acta biológica Colombiana 15 (1): 237-244. [in Spanish]

Mayor-Victoria, R., Botero-Botero, A. (2010b). Uso del hábitat por la nutria neo-tropical Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora: Mustelidae) en el río Roble, Alto Cauca, Colombia. Bol. Cient. Mus. Hist. Nat. 14(1):121-130. [in Spanish]

Mayor-Victoria, R. (2008). Hábitat y dieta de la nutria neotropical Lontra longicaudis (Carnívora, Mustelidae) en el río Roble, Alto Cauca, Colombia. Biology Thesis. Universidad del Quindío, Programa de Licenciatura en Biología y Educación Ambiental, Armenia-Colombia.

Quadros, J., Monteiro-Filho, E. (2001). Diet of the Neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis in an Atlantic forest area, Santa Catarina state, southern Brazil. Stud. Neotrop. Fauna E. 36(1): 15-21.

Restrepo, C., Botero-Botero, A. (2012). Ecología trófica de la nutria neotropical Lontra longicaudis (Carnívora, Mustelidae) en el río La Vieja, alto Cauca, Colombia. Bol. Cient. Mus. Hist. Nat. 16(1): 207-214. [in Spanish]

Rosales, Y. (2009). Dieta de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis) en la vertiente sur andina venezolana. MSc. Thesis. Universidad Nacional Experimental de los Llanos Occidentales “Ezequiel Zamora” UNELLEZ, Venezuela. [in Spanish]

Waldemarin H.F. (2004). Ecologia da lontra neotropical (Lontra longicaudis), no Trecho Inferior Da Bacia Do Rio Mambucaba, Angra Dos Reis. PhD. Thesis. Universidade Do Estado Do Rio De Janeiro, Brasil. [in Portuguese]

Zuluaga-Gómez, A., Giarrizzo, T., Andrade, M., Arango-Rojas, A. (2014). Length–weight relationships of 33 selected fish species from the Cauca river basin, trans-Andean region, Colombia. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 30(5): 1077-1080.

Resumé: Le Régime Alimentaire De Lontra Longicaudis Dans La Rivière Espejo, Quindio, Colombie

Nous avons étudié le régime alimentaire de la loutre à longue queue, Lontra longicaudis, dans la rivière Espejo (département de Quindío, Colombie). Cette rivière a les plus hauts niveaux de pollution du bassin versant de la rivière La Vieja. Nous avons parcouru une section de la rivière de 5,6 km à neuf reprises au cours du mois de juillet 2009 et avons recueilli 131 épreintes. Les échantillons de matières fécales ont été lavés, tamisés et leur contenu examiné. Les échantillons d’excréments ont indiqué que le régime alimentaire de la loutre dans cette rivière est principalement composé de poissons comprenant sept espèces capturées. Les proies les plus courantes étaient Hypostomus sp. (31.6 % des échantillons) et Brycon henni (29.22 % des échantillons).

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Dieta de Lontra Longicaudis en el Río Espejo, Quindío, Colombia

Estudiamos la dieta de la nutria Netropical, Lontra longicaudis, en el Río Espejo (Departamento del Quindío, Colombia). Este río presenta los más altos niveles de contaminación en la Cuenca del Río la Vieja en esta región. 5.6 km del río fueron muestreados en nueve ocasiones durante el mes de Julio de 2009, donde se colectaron 131 muestras fecales de las nutrias. Las muestras fueron lavadas, tamizadas y analizadas. La dieta de la nutria en el río Espejo se compone principalmente de siete especies de peces depredadas. Las presas más comunes fueron Hypostomus sp. (31% del total de muestras) y Brycon henni (29% del total de muestras).

Vuelva a la tapa