IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Citation: Vázquez-Maldonad, L., Delgado-Estrella, A. and Gallo-Reynoso, J.P. (2021). Knowledge and Perception of the Neotropical Otter (Lontra longicaudis annectens) by Local Inhabitants of a Protected Area in the State of Campeche, Mexico. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 38 (3): 155 - 172

Knowledge and Perception of the Neotropical Otter (Lontra longicaudis annectens) by Local Inhabitants of a Protected Area in the State of Campeche, Mexico

Laura Elena Vázquez-Maldonado1*, Alberto Delgado-Estrella1 and Juan Pablo Gallo-Reynoso2

1Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Campus III, Universidad Autónoma del Carmen. Av. Central S/N Esq. with Fracc. Mundo Maya, Cd. del Carmen 24115, Campeche, México

2Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo A.C., Unidad Guaymas. Carretera al Varadero Nacional km 6.6, Las Playitas, Guaymas 85480, Sonora, México

* Corresponding Author Email: lauvamaster@gmail.com

(Received 5th October 2020, accepted 5th December 2020)

Abstract: The Neotropical otter is a protected species under the Mexican General law of wildlife listed as threatened (NOM-059-ECOL-2010); it is listed as near-threatened by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and in Appendix I of CITES. The Neotropical otter is mentioned in the management program for the Laguna de Términos federal protected area but is seldom mentioned in other management programs of protected areas of Mexico. As very few scientific studies conducted in the State of Campeche make reference to the Neotropical otter, we conducted a survey among the inhabitants of the margins of the Laguna de Términos system to learn about their perceptions of this species. Data were gathered from June to October 2015 through an ad hoc questionnaire applied to 101 local inhabitants. We asked questions about their empirical knowledge of the biology of the Neotropical otter and their perception of the status of the species. Data were summarized in terms of percentages and subjected to statistical analyses (Kruskal-Wallis tests) for comparison and interpretation. We found that the local inhabitants are familiar with Neotropical otters and provided candid and consistent information. They showed some ambivalence with regard to the protection of the species: although they recognized the conservation status of the species, they also admitted that otters are occasionally exploited (hunting for their fur) as a source of revenue. Most respondents (94-100%) supported establishing a conservation plan. This information should be taken into account when planning and implementing eco-tourism activities in the Laguna de Términos protected area.

Keywords: Neotropical otter, Surveys, Laguna de Términos, protected area

INTRODUCTION

The Neotropical otter, Lontra longicaudis (Olfers, 1818), is widely distributed in Mexico, where it can be found in almost all streams, lakes, dams, lagoons and large rivers on the coastal plains of the Atlantic and Pacific slopes (Gallo-Reynoso 1989, 1991; Ramírez-Bravo, 2010). It is a versatile species that can easily adapt to a wide range of riparian habitats, from arid regions with thorny scrub vegetation, oak-pine forests, to evergreen and deciduous tropical forests (Gallo-Reynoso, 1989, 1997; Cirelli, 2005; Botello et al., 2006).

The Neotropical otter, locally known as perro de agua (literally, water dog), is a polytypic species. The subspecies L. l. annectens (Major, 1897) is listed as near-threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (Rheingantz and Trinca, 2015) and is included in Appendix I (endangered) of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES, 2018). In Mexico, it is listed as threatened by the official Mexican standard NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (SEMARNAT, 2010).

This species is well-known in Mexico. Efforts to study the Neotropical otter have been increasing since the year 2000. Santiago-Plata (2009) compiled the studies on this species carried out in Mexico. His results and those obtained in more recent studies show that most studies have focused on evaluating the habitat of the otter, as well as on biological and ecological aspects related to its food preferences (Table 1) and relative abundance (Table 2) in different parts of Mexico, including the States of Campeche, Chiapas, Colima, Guerrero, Jalisco, Michoacan, Nayarit, Oaxaca, Quintana Roo, Sonora, State of Mexico, Tabasco, and Veracruz.

| Table 1: Studies focused on food preferences of the Neotropical otter in Mexico. Modified from Mariano-Mendoza (2019). | |||||||||||||||

Author |

FN | Locality | Prey (%) | ||||||||||||

| Pla | Mo | Ins | Cr | Fis | Am | Re | Bi | Ma | |||||||

| Gallo-Reynoso (1989) | 35 | Sierra Madre del Sur (Nayarit, Jalisco, Colima, Michoacan, Guerrero, Oaxaca states) | + | - | 11,6 | 34,8 | 46,9 | 2,1 | 1,7 | 1,7 | 1,2 | ||||

| Gallo-Reynoso (1996) | - | Yaqui River, Sonora | - | - | - | - | 95,0 | - | - | - | - | ||||

| Macías-Sánchez and Aranda (1999) | 474 | Los Pescados River, Veracruz | - | - | 7,5 | 30,8 | 54,1 | - | 6,2 | 1,4 | - | ||||

| Ramón (2000) | 106 | San Cipriano River, Tabasco | - | - | 6,4 | 20,1 | 70,7 | - | 0,6 | - | 1,9 | ||||

| Arellanes-Licea and Briones- Salas (2003) | - | Zimatan River, Oaxaca | 2,4 | - | 3,9 | 55,6 | 37,1 | - | - | 0,2 | - | ||||

| Casariego- Madorell (2004) | 580 | Three rivers in the State of Oaxaca | - | - | 9,8 | 53,1 | 33,1 | 6,2 | - | - | - | ||||

| Soler-Frost (2004) | 524 | Four streams in the Lacandona tropical rian forest, State of Chiapas | 7,7* | 2,8 | 21,2 | 1,5 | 61,6 | - | 1,7 | - | 2,7 | ||||

| Díaz-Gallardo et al., (2007) | 186 | Ayuquila River, Jalisco | 0,5** | - | 23,1 | 35,1 | 36,1 | - | 1,6 | 1,6 | 1,8 | ||||

| Duque-Dávila (2007) | 161 | Grande River, Oaxaca | 0,2 | - | 4,1 | - | 89,6 | - | 4,3 | 1,7 | - | ||||

| Rangel-Aguilar and Gallo-Reynoso (2013) | 73 | Bavispe-Yaqui River, Sonora | - | 1,5 | 30,0 | - | 58,0 | - | 1,5 | 5,8 | 3,7 | ||||

| Grajales- García et al., (2019) | 67 | Coastal area of Tuxpan, Veracruz | - | 8,6 | 4,9 | 55,5 | 22,2 | 1,2 | - | 6,2 | 1,2 | ||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Table 2 : Studies focused on the relative abundance of the Neotropical otter in Mexico (in chronological order). Modified from Santiago-Plata (2009). | |||||||

| Number | Estimated abundance (otters/km) | Distance traveled (km) | Method used | Study area | Reference | ||

| 1 | 0.50 | 11.0 | DR (3 spraints per day) | Catemaco Lagoon, Veracruz | Ruiz-Betancourt (1992) | ||

| 2 | 0.34 | 73 000 * | DR (3 spraints per day) | Yaqui River, Sonora | Gallo- Reynoso (1996) | ||

| 3 | 0.21 | 107.5 | Traces, direct observations | Hondo River, Quintana Roo | Orozco-Meyer (1998) | ||

| 4 | 2.45- 6.26 | 20.0 | DR (3 spraints per day) | Los Pescados and Actopan rivers, Veracruz | Macías-Sánchez (2003) | ||

| 5 | 1.22- 3.10 | 20.0 | DR (6 cub spraints per day) | Los Pescados and Actopan rivers, Veracruz | Macías-Sánchez (2003) | ||

| 6 | 0.42 | 707.1 | Number of spraints or number of latrinas/km | Ayuta, Copalita and Zimatan rivers, coast of Oaxaca. | Casariego-Madorell (2004) | ||

| 7 | 1.26 | 707.1 | DR (3 spraints per day) | Ayuta, Copalita and Zimatan rivers, coast of Oaxaca. | Casariego-Madorell (2004) | ||

| 8 | 0.38 | 68.0 | DR (3 spraints per day) | Nayarit | Macías-Sánchez and Hernández (2007) | ||

| 9 | 1.89 | 39.0 | -Number of spraints/km | Tlacotalpan, Veracruz | Arellano-Nicolás (2008) | ||

| 0.38 | -Number of latrinas/km | ||||||

| 0.48 | -DR (3 spraints per day) | ||||||

| 10 | 0.52 | - | DR (3 spraints per day) | Yaqui River, Sonora | Rangel-Aguilar (2008) | ||

| 12 | 0.001-0.023 | 9.0 | DR (3 spraints per day) | Temascaltepec River, State of México | Guerrero-Flores et al. (2013) | ||

| 13 | 0.0005-0.011 | 9.0 | DR (6 cub spraints per day) | Temascaltepec River, State of Mexico | Guerrero-Flores et al. (2013) | ||

| 14 | 0.97 | 39.0 | DR (3 spraints per day) | Catemaco Lagoon, Veracruz | González-Christen et al. (2013) | ||

| 15 | 0.49 | 39.0 | DR (6 cub spraints per day) | Catemaco Lagoon, Veracruz | González-Christen et al. (2013) | ||

| 16 | 0.12 | 5.0 | -DR (3 spraints per day) (Number of spraints/ storage time of spraints*)/km | Pantanos de Centla, Biosphere Reserve, Tabasco (RBPC) (San Pedrito) | Jiménez-Domínguez and Olivera-Gómez (2018) | ||

| 17 | 0.4 | 5.0 | -DR (3 spraints per day) (Number of spraints/ storage time of spraints*)/km | RBPC (Tabasquillo Stream, Tabasco) | Jiménez-Domínguez and Olivera-Gómez (2018) | ||

| 18 | 0.93 | 5.0 | -DR (3 spraints per day) (Number of spraints/ storage time of spraints*)/km | RBPC (La Gloria Stream, Tabasco) | Jiménez- Domínguez and Olivera-Gómez (2018) | ||

| 19 | 0.02 | - | DR (3 spraints per day) | Tampamachoco Lagoon, Tuxpan, Veracruz | Grajales-García et al. (2019) | ||

| 20 | 0.14 | - | DR (3 spraints per day) | Tumilco Stream, Tuxpan, Veracruz | Grajales-García et al. (2019) | ||

| 21 | 0.94 | - | DR (3 spraints per day) | Jácome Stream, Tuxpan, Veracruz | Grajales-García et al. (2019) | ||

| DR= Defecation rate | * Distance traveled (l m-wide line) | ||||||

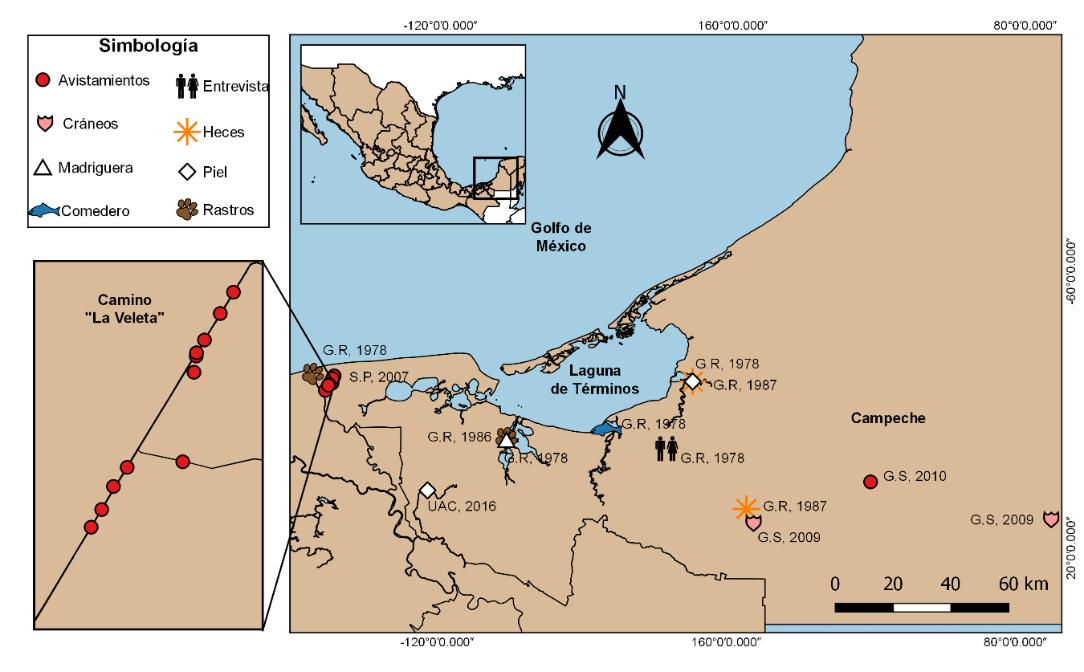

The population of L. l. annectens (Major, 1897) in the State of Campeche is likely to have a wider distribution and higher abundance than what has been reported in the literature to date. However, the paucity of biological and ecological data collected in the State made it impossible to confirm this assumption. Fewer than 30 studies have been published since 1989, and some of those remained as gray literature (i.e., dissertations, thesis, technical reports and others), with limited distribution, or confirming the presence of the species in the State. Therefore, we first conducted an extensive review of the literature for the State of Campeche and found few scientific papers have been produced. The earliest report was by Gallo-Reynoso (1989) who in 1978 found indirect records (footprints and spraints) of the presence of the Neotropical otter in the Usumacinta River delta and in the upper areas of the Candelaria, Samaria, Chumpan, and Palizada rivers and Del Este Lagoon, whose waters flow into the Laguna de Términos (Términos Lagoon). Other records of the presence of the Neotropical otter were reported by Santiago-Plata (2009) and Santiago-Plata et al. (2013) for the Laguna de Términos federal protected area (APFFLT, for its acronym in Spanish). They found indirect records and documented sightings of L. l. annectens on the San Pedro-San Pablo River, which marks the boundary between the Campeche and Tabasco states, additional evidence of the presence of the otter was found subsequently (Table 3).

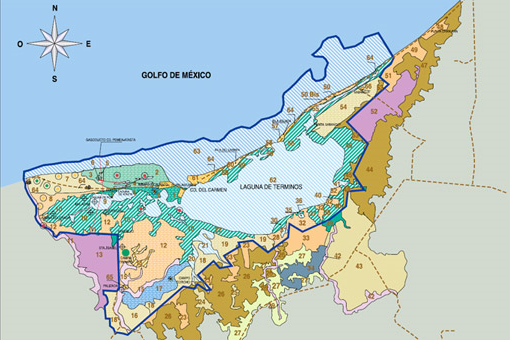

The Centro de Estudios de Desarrollo Sustentable y Aprovechamiento de la Vida Silvestre (Center for Studies on Sustainable Development and Use of Wildlife, CEDESU for its acronym in Spanish) at Universidad Autónoma de Campeche (UAC), hold three records of Neotropical otters: two skulls and one sighting in their mammal collection (Guzmán-Soriano et al., 2013). In addition, we visited Palizada Town in January 2015 to corroborate the presence of the Neotropical otter in the area; this was confirmed by Mr. J. Carvallo (Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas, National Commission for Protected Areas, CONANP for its acronym in Spanish) and by managers of the San Román Ranch located near Palizada Town. Finally, we accessed at Unidad Informática para la Biodiversidad, specificaly the database of the Colección Nacional de Mastozoología (National Mammalogy Collection) of the Instituto de Biología, UNAM. We found a single record of this species for the State of Campeche, dated in 1986, with incomplete location data for the point of collection (Table 3) (Fig. 1).

The presence at least one of the two species of river otters, Lontra canadensis and L. longicaudis, has been recorded in 23 of the protected areas of Mexico (Gallo-Reynoso et al., 2019). However, the management programs of most of those protected areas do not make any reference to otters. This is not the case of the Laguna de Términos protected area; its management program (INE, 1997) includes the Neotropical otter in the list of vertebrates inhabiting the reserve (p. 27) and describes its distribution in the fluival-lagoon and estuarine systems such as the Sabancuy, Panlao, Balchacah, and Puerto Rico lagoons and the Chumpan and Palizada rivers; the information included therein was provided by one of us (Gallo-Reynoso). The document also called for studies on the population dynamics of this species in order to support decisions regarding its protection and management (p. 43): "Formulate and implement special protection measures for habitats of threatened, vulnerable, or endangered species including, among others: jabiru, manatee, otter, crocodile, sea turtles and fresh water tortoises". Unfortunately, no follow-up on the management program has been documented and, thus, the progress or implementation status of such actions is unknown.

It is essential to design and implement strategies and policies for the study, protection, and monitoring of Neotropical otters. Information needs include determining their regional population trends; identify and evaluate the pressures affecting them; and, based on that, design actions to promote their conservation. Several surveys have shown that people, in general, regard otters as charismatic animals (Gallo-Reynoso, 1997; Macías-Sánchez, 2003; Kruuk 2006; Guerrero-Flores, 2007). This perception is advantageous, as it can facilitate public participation in conservation efforts for Neotropical otters. As otters are intimately linked to wetlands, such efforts would also result in the conservation of entire habitats, many of which are currently threatened and, consequently, of many other species inhabiting the same area and habitats (Guerrero-Flores et al., 2013).

There is a clear need to conduct further research to provide the necessary knowledge on the current situation of the Neotropical otter in the Laguna de Términos protected area, encompassing all the fluvial-lagoon systems therein. Part of this information can be gathered through more extensively surveys of local residents to learn about their views on this species; such information would provide the basis for designing and implementing applied research aimed to the conservation of this species.

STUDY AREA

The Laguna de Términos protected area for flora and fauna (APFFLT) is located in the Southwest part of the State of Campeche. It includes the entire Laguna de Términos Lagoon, and parts of the municipalities of Carmen, Champoton and Palizada (Fig. 2). The APFFLT is one of the largest protected areas of Mexico; it incorporates a total area of 706.147 ha, with 351.582 ha of terrestrial and 353.434 ha of aquatic areas, of which 200.108 ha correspond to the lagoon-estuarine ecosystems (INE, 1997). The coastal plain is part of the complex deltaic plain of the Grijalva-Usumacinta River, whose freshwater discharges is the largest in Mexico, and encompasses a variety of biodiversity-rich ecosystems that harbor a number of species listed as threatened, endangered, or under special protection by the Mexican official standard NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (SEMARNAT, 2010).

The prevailing climate in the area is humid tropical, with three well-marked seasons along the year (Yáñez-Arancibia and Day, 1988): 1. dry season (February to May), 2. rainy season (June to September) and 3. “nortes” or northern wind season (October to January); with February and May as transitional months when occasional “nortes” and rains occur, respectively (Villalobos-Zapata et al., 2002; Guerra-Santos and Kahl, 2018).

Freshwater inputs from rivers throughout the year play an important role in the dynamics of the lagoon system due to the mixing of water and the natural circulation of Laguna de Términos. Tides are semi-diurnal, with a 50-60 cm tidal range (Ramos-Miranda et al., 2006).

The main economic activities carried out within the protected area (as of 2017) are related to fisheries. There are fishermen (fishing being a men-only activity), fishing permit holders, president of fishing cooperative, government manager, and company manager; women participate in the last two activities (Crespo-Guerrero, 2017). Other activities that are carried out in the protected area, although to a lesser extent, include those related to the oil industry as well as commercial, services, and agricultural activities (INEGI, 2016). However, the 2015-2021 Development Plan of the State of Campeche stresses that the main economic activities in Campeche and in the Laguna de Términos protected area relate to the oil industry.

It is important to bear in mind that fishing activities in coastal wetlands of the Gulf of Mexico had a high economic impact in the past, when they accounted for up to 30% of the total catch of the country (Yáñez-Arancibia and Day, 2004). However, the activity declined from 2010 to 2015, with sporadic peaks when fishermen were hired on a temporary basis, depending on the fishing season (Secretaría de Pesca y Acuacultura, 2015). Coastal fisheries contribute with approximately 80% of the local economy in coastal towns. However, fisheries resources of the Gulf of Mexico have been overexploited and wetlands have been either destroyed or degraded by urban expansion and the construction of channels diverting water for irrigating crops (Yáñez-Arancibia and Day, 2004). The major issues affecting riverine fisheries in Mexico include illegal fishing, insufficient and unsupervised inspection, lack of organization and administrative order, poor practices in the sales and marketing of products (Secretaría de Pesca y Acuacultura, 2015). There is an urgent need for a comprehensive management program of the coastal areas of the reserve. Integrating cultural, economic, and ecological values, as well as reaching a balance between environmental protection and economic development, are key for a successful management program for the Laguna de Términos protected area.

METHODS

The management program of the Laguna de Términos protected area for flora and fauna (INE, 1997), describes the presence of the Neotropical otter on the margins of the fluvio-lagoon system of the protected area. However, the perception and knowledge of local residents about Neotropical otters were largely unknown. Thus, we conducted a perception survey among 101 local inhabitants in five localities within the Laguna de Términos protected area over a five-month period (Table 4).

The questionnaire included 40 questions covering various aspects, from personal data such as gender, age, education level, and social-economic situation; knowledge about basic aspects of the biology of the Neotropical otter such as behavior and habitat use; and questions about their perception of the economic importance and conservation of the Neotropical otter.

The information thus gathered was sorted, percent frequencies of the responses were calculated, and statistical analyses (Kruskal-Wallis tests) were carried out for interpretation using Statistica Software version 7.0, p-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Overall, most respondents (62%) were men age 40 to 60 years old. Although several jobs or trades were mentioned, fishing was their primary economic activity. Most fishermen have basic educational level only, but a few of them (4% in Atasta and 8% at La Puntilla) have completed higher-level studies. All respondents had heard of the Neotropical otter, referring to it as perro de agua (literally, water dog).

Sightings of otters were frequent (50% of the respondents in Atasta and 56% in Palizada); the most recent sighting occurred less than one month before the survey in Palizada. Elsewhere, sightings of Neotropical otters had been sporadic, separated by at least one year. Respondents from all the localities surveyed have the perception that sightings used to be more frequent in the past than they are now.

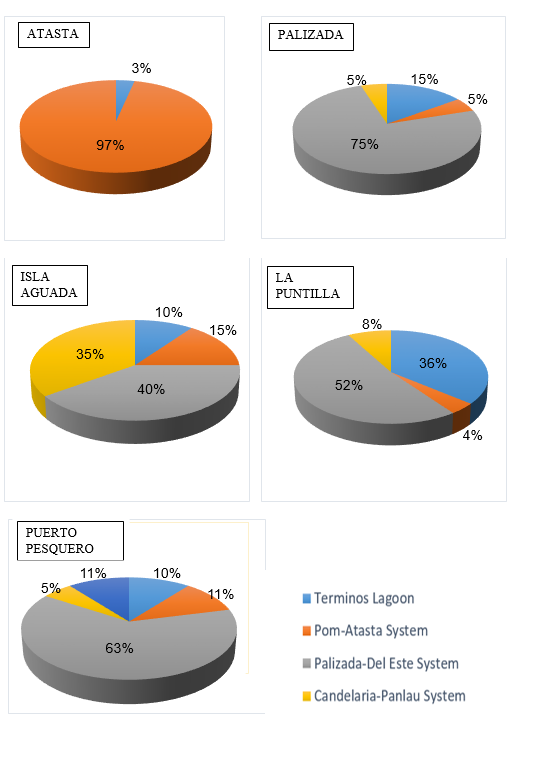

Most sightings occurred in areas around households or in fishing grounds. For instance, anglers from La Puntilla and Puerto Pesquero spotted otters at Palizada; fishermen of Isla Aguada saw otters in the Candelaria-Panlao lagoon system and the Palizada River (Fig. 3). Sightings were most frequent during the dry season. The respondents demonstrated a fairly extensive knowledge of the species and were able to identify all the activities of Neotropical otters (swimming and feeding), the time of day when the otters are active (during the morning until noon) and what they eat (fish and crustaceans).

In most cases (56 to 73%), single otters were seen. Although groups of two or three individuals have been observed, in most cases females with calves were observed. Atasta (79%) and Palizada (62%) are the locations where group sightings have been recorded more frequently; there was a significant difference with the rest of the localities (H>0.05). Group sightings were recorded during the dry season.

Not all respondents were able to differentiate between otter sexes; however, those who were able (42%) took into account the following two criteria: body size and fur coloration, males are larger and darker than females (consistent with the criteria used by Gallo-Reynoso, 1989).

Respondents claimed to detect the presence of otters by their tracks (spraints and footprints) and by the location of the dens. This is consistent with reports in the literature describing that dens are usually constructed at the base of trunks (Gallo-Reynoso, 1989; Pardini and Trajano, 1999; Macías-Sánchez, 2003), in this case: mangrove swamp areas, amid the aerial roots of mangroves trees (Fig. 4).

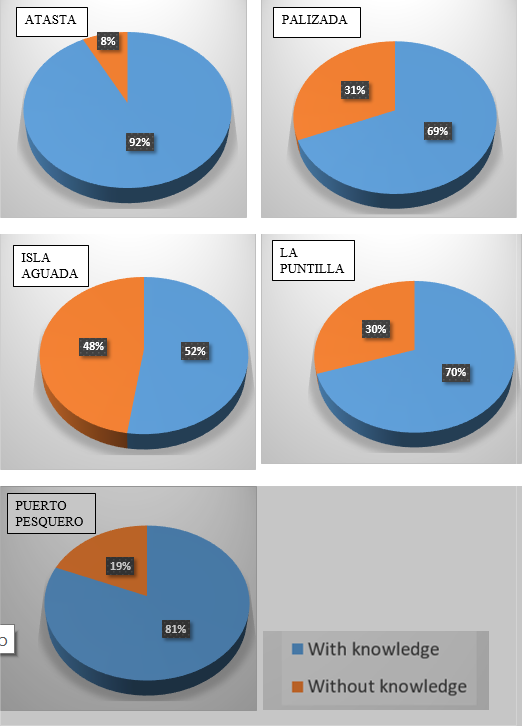

The majority of respondents (62% in Palizada, 96% in Atasta) live within the federal protected area and most of them (52% in Isla Aguada, 92% in Atasta) and are aware that the Neotropical otter is a species protected under the Mexican Ley General de Vida Silvestre (General Wildlife Law) for being a threatened species. However, there was a significant difference (H>0.05) between Isla Aguada and the other localities, where fewer people were aware of the conservation status of the otter (Fig. 5).

There was an ambivalent position on this regard, as this species is exploited as a resource to some extent in all localities. The respondents mentioned using the otter fur (94% in Palizada), having otters as pets (21 to 33 %), consuming the meat, or trading entire specimens (7% in La Puntilla and 11% in Puerto Pesquero). There are records of otter hunting, usually by shooting or setting traps with bow and bait hook.

Among the most significant finding of this surveys is that the majority of respondents (94 to100%) would support establishing a program for the conservation of the Neotropical otter, and they also expressed (45 to 92%) their willingness to attend workshops informing on otter conservation These findings can inform decision-making and actions to be taken for the protected area (APFFLT) to protect otters and their habitat. The respondents were also in favor (45 to 96%) of disseminating information so that the species can be protected in their locality and were willing (45 to 95%) to participate in the outreach efforts.

Isla Aguada was the locality that yielded the lowest percentages in all the aspects addressed in the questionnaire. When asked why they were in favor, the local respondents pointed out that there are a few otters (this locality is in a more coastal zone) and they cause no harm.

One of the factors assessed was whether the local community perceives a conflict of interest between their activities and the Neotropical otter. Interestingly, perception on conflict of interest ranged from nil to minor, with the highest percentage in Puerto Pesquero (25%). Some respondents mentioned that otters steal fish (37 to 50%) or break nets or traps (25 to 60%). In contrast, respondents from Isla Aguada reported 0% conflicts.

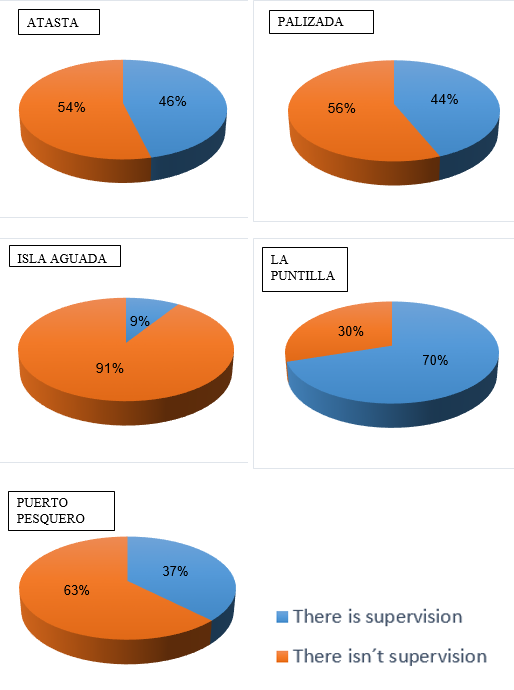

Another factor addressed that caught our attention was the perception of local residents on the actions to protect the Neotropical otter by the federal, state, or municipal authorities. In four of the five localities surveyed, it was mentioned that there is insufficient supervision (Atasta 54%; Palizada 56%; Isla Aguada 91%, and Puerto Pesquero 63%); Isla del Carmen-La Puntilla was the only location where 70% of respondents expressed that there is adequate supervision (Fig. 6). This information should be important for the authorities in charge of the reserve.

It is also important to know the characteristics of the local inhabitants, as these should be properly taken into account when designing strategies for the conservation of the Neotropical otters, particularly if environmental education activities are to be carried out as part of the otter conservation strategy. Most respondents have only elementary education; therefore, any documents to be used as part of environmental education activities should be easy to read and written in simple terms.

Since fishing is the main economic activity of the respondents and both humans and otters coexist in the same area, human interactions with otters are common. These interactions should be taken into account when updating the management program of the Laguna de Términos protected area, since both humans and otters exploit the same natural resources in the same fishing grounds.

One particular aspect that we aimed to investigate through the survey was whether there is any conflict of interest between humans and the Neotropical otter, as reported by Guerrero-Flores et al. (2013). This is an important aspect that should be addressed in any otter conservation program, as respondents consider that otters should be protected because they cause neither harm nor damages.

From the responses to the survey, it is clear that local inhabitants have a fair knowledge of otters; they provided candid responses and consistent information on the species. Many of them know some aspects of the otter biology: activities carried out by otters, time of the day when they perform them, what they eat, and places where they can be observed; local inhabitants are also able to detect the presence of otters through tracks (footprints). All the information provided was consistent with data reported by other authors for other regions within the distribution range of the Neotropical otter (Gallo-Reynoso, 1991, 1996, 1997; Casariego-Madorell, 2004; Briones et al., 2008; Briones-Salas et al., 2013; Duque-Dávila et al., 2013; Guerrero-Flores et al, 2013; Mayagoitia-González et al., 2013; Santiago-Platas et al., 2013). However, otter groups with more than two individuals were rarely seen.

Gathering information on the Neotropical otter (L. l. annectens) in the Laguna de Términos protected area for flora and fauna by surveying local inhabitants helped to set the bases to formulate a comprehensive management program that strengthens the local conservation of the species and affects the conditions that should occur in the Laguna de Términos protected area to be considered for developing economic activities. Since 2003, the local government has been promoting tourism as a development economic activity alternative to oil production (Pat-Fernández and Calderón-Gómez, 2012).

The conditions in the Laguna de Términos protected area for developing ecotourism activities (such as boating, wildlife sighting, and kayaking) are very similar to those found in other areas such as the La Vega Escondida protected area in the State of Tamaulipas. In the latter, the approach proposed in the management program for conserving the Neotropical otter was to regard it as an “umbrella species” (Mayagoitia-González et al., 2013), emphasizing the functional links between otters and other species in the same ecosystem (Bifolchi and Lodé, 2005), because their presence is indicative of high energy availability and high biodiversity (Gallo- Reynoso et al., 2008). Mayagoitia-González et al. (2013) also highlighted the importance of convening outreach workshops to raise awareness on the importance of wetlands.

Macías-Sánchez (2003) mentions that otters are a bioindicator species of the ecosystems that can be used as tools for ecosystem conservation. In other words, a comprehensive management program should be formulated including the local inhabitants, where ecological benefits should include a viable habitat for the otter and social awareness on the Neotropical otter as an umbrella species for the conservation of entire ecosystems.

The Neotropical otter is also a charismatic species, attractive for zoos and considered as a keystone or flagship species (Soler, 2002). Flagship species enjoy sympathy of the general public; the intrinsic appeal of otters facilitate raising awareness about the importance for their conservation. The giant panda, seals, quetzals, and big cats are typical examples of flagship species. They are often included in the logos of organizations dedicated to wildlife conservation (INECC, 2013). A similar study carried out in the State of Veracruz focused on elucidating the conservation status of the species and proposed a program for the management of otter populations (Arellano-Nicolás, 2008).

The uses of the Neotropical otter in Campeche are mostly unknown. The few data available indicate that it has ornamental use (Gallo-Reynoso, 1997); there is also evidence of its use as pets, and its fur is used for manufacturing accessories such as wallets or belts (obs. pers.). Basic studies such as the one reported here provide useful information for planning and conducting further research on this species in the Laguna de Términos protected area.

Acknowledgements: We deeply thank all team members, students of the Marine Biology EP at UNACAR: A. Rodríguez Moreno (Pom-Atasta); C.S. Montes de Oca Moreno and G. Arriola Ramírez (Isla Aguada); J.A. Ramírez Yáñez and P.R. Chandoqui Chame (Cd. del Carmen); K.L. Naranjo Ruiz, T.A. Cárdenas Acosta, V.G. Mariano Mendoza, D.M. Montero Flores, P.R. Chandoqui Chame, C.S. Montes de Oca Moreno; and I.A. Gómez Evia (Palizada-Este). We also thank Mr. O.G. Retana Guiascón of the scientific collection of the Centro de Estudios de Desarrollo Sustentable y Aprovechamiento de la Vida Silvestre (CEDESU-Universidad de Campeche). We also thank Mr. U.M. Samper-Palacios and Ms. J. Vargas that kindly granted access to the database of the Colección Nacional de Mastozoología. M. E. Sánchez-Salazar edited the English manuscript. This work was carried out under SEMARNAT permits No. SGPA/DGVS/09059/15 and SGPA/DGVS/15249/15.

REFERENCES

Arellanes-Licea, E. L., Briones-Salas, M. (2003). Hábitos alimentarios de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en el río Zimatán, Costa de Oaxaca, México. Mesoamericana 7: 1-7.

Arellano-Nicolás, E. (2008). Estado de Conservación y Propuesta de Plan de Manejo para las Poblaciones de Lontra longicaudis en Tlacotalpan, Veracruz. Informe Final de Servicio Social. División de Ciencias Biológicas y de la Salud. UAM. México, D.F.

Arellano, N.E., Sánchez, E., Mosqueda, M.A. (2012). Distribución y abundancia de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en Tlacotalpan, Veracruz, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana 28: 270-279.

Bifolchi, A., Lodé, T. (2005). Efficiency of conservation shortcuts: an investigation with otters as umbrella species. Biological Conservation 126: 523-527.

Botello, F., Salazar, J.M., Illoldi-Salazar, P., Linaje, M., Monrroy, G., Duque, D., Sánchez-Cordero, V. (2006). Primer registro de la nutria de río neotropical (Lontra longicaudis) en la Reserva de la Biósfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán, Oaxaca, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 77: 133-135.

Briones, S.M., Cruz, J.A., Gallo-Reynoso, J.P., Sánchez-Cordero, V. (2008). Abundancia de la nutria neotropical de río (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897) en el Río Zimatan en la Costa de Oaxaca México. In: Lorenzo, C., Medinilla, E., Ortega, J. (Eds.). Avances en el Estudio de los Mamíferos de México II. Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología, A. C. (AMMAC), Cd. de México, México, pp. 354-376.

Briones-Salas, M., Peralta-Pérez, M.A., Arellanes, E.(2013). Análisis temporal de los hábitos alimentarios de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis) en el rio Zimatán en la costa de Oaxaca, México. Therya. 4:311-326

Carrillo-Rubio, E. (2002). Uso, características y modelación del hábitat de la nutria de río neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major 1897) en el Bajo Río San Pedro, Chihuahua. Master's thesis. Facultad de Zootecnia, Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua, México.

Casariego-Madorell, M.A. (2004). Abundancia relativa y hábitos alimentarios de la nutria de río (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en la costa de Oaxaca, México. Master's thesis. Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México.

Cirelli, V. (2005). Restauración ecológica en la cuenca Apatlaco-Tembembe. Estudio de caso: modelado de la distribución de la nutria de río. Master's thesis. UNAM, México.

CITES (Convención sobre el Comercio Internacional de Especies Amenazadas de Fauna y Flora Silvestres). (2018). Apéndice I, II y III, en vigor a partir del 04 de octubre de 2017. Abril 09, 2019. http://www.cites.org/esp/app/appendices.shtml

Crespo-Guerrero, J.M. (2017). El trabajo de campo en la investigación geográfica de la pesca comercial riberaña en las Áreas Naturales Protegidas del estado de Campeche, México. Investigaciones geográficas, Instituto de Geografía, UNAM, Agosto (93): 1-11.

Cruz-Alfaro, J. (2000). Abundancia relativa de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) del río Zimatán, Costa de Oaxaca, México. Bachelor's thesis. Instituto Tecnológico Agropecuario de Oaxaca, Mexico.

Díaz-Gallardo, N., Iñiguez-Dávalos, L.I., Santana, E. (2007). Ecología y conservación de la nutria (Lontra longicaudis) en la Cuenca Baja del Río Ayuquila, Jalisco. In: Sánchez-Rojas, G., Rojas-Martínez, A. (Eds.). Tópicos en sistemática, biogeografía, ecología y conservación de mamíferos. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, Instituto de Ciencias Básicas e Ingeniería, Pachuca, México, pp. 165-182.

Duque-Dávila, D.L. (2007). Distribución, abundancia y hábitos alimentarios de la nutria (Lontra longicaudis annectens MAJOR, 1897) en el Río Grande, Reserva de la Biosfera Tehuacan-Cuicatlán, Oaxaca, México. Bachelor's thesis. Facultad de Estudios Superiores. UNAM. México.

Gallo-Reynoso, J.P. (1989). Distribución y estado actual de la nutria o perro de agua (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897) en la Sierra Madre del Sur, México. Master´s thesis. Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México.

Gallo-Reynoso, J.P. (1991). The status and distribution of rivers otters (Lutra longicaudis annectens, Major, 1897), in México. Habitat 6: 57-62.

Gallo-Reynoso, J. P. (1996). Distribution of the neotropical river otters (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897) in the Río Yaqui, Sonora, México. IUCN Otter Specialists Group Bulletin 13(1): 27-31.

Gallo-Reynoso, J.P. (1997). Situación y distribución de las nutrias en México, con énfasis en Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología 2: 10-32.

Gallo-Reynoso, J.P., Ramos-Rosas, N.N., Rangel-Aguilar, O. (2008). Depredación de aves acuáticas por la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens), en el río Yaqui, Sonora, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 79: 275-279.

Gallo-Reynoso, J.P., Macías-Sánchez S., Núñez-Ramos V.A., Loya-Jacquez A., Barba-Acuña I.D., Aremnta-Mendez L. del C., Guerrero-Flores J.J., Ponce-García G., Gardea-Bejar A.A. (2019). Identity and distribution of the Nearctic otter (Lontra canadensis) at the Río Conchos Basin, Chihuahua, México. Revista Therya 10: 243-253.

González-Christen, A., Delfín-Alfonso, C.A., Sosa-Martínez, A. (2013). Distribución y abundancia de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897), en el Lago de Catemaco Veracruz, México. Revista Therya 4: 201-217.

Grajales-García, D., Serrano A., Capistrán-Barradas A., Naval-Ávila C., Pech-Canché J.M., Becerril-Gómez C. (2019). Hábitos alimenticios de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) (Carnivora: Mustelidae) en la zona costera de Tuxpan, Veracruz. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 90: e902502

Guerra-Santos, J.J., Kahl, J.D.W. (2018). Redefining the seasons in the Terminos Lagoon Region of Southeastern Mexico: May is a transition Month, Not a Dry Month. Journal of Coastal Research 34: 193-201.

Guerrero-Flores, J. (2007). Evaluación del hábitat de la nutria (Lontra longicaudis) en tres ríos de Temascaltepec, Estado de México. Bachelor's thesis. Universidad Autónoma del estado de México, Toluca, México.

Guerrero-Flores J.J., Macías-Sánchez, S., Mundo-Hernández, V., Méndez-Sánchez, F. (2013). Biología de la nutria (Lontra longicaudis) en el municipio de Temascaltepec, estado de México: estudio de caso. Revista Therya 4: 231-242.

Guzmán-Soriano, D., Vargas-Contreras, J.A., Cú-Vizcarra, J.D., Escalona- Segura, G., Retana-Guiascón, O.G., González-Christen, A., Benítez- Torres, J.A., Arroyo-Cabrales, J., Puc-Cabrera, C., Victoria-Chán, E. (2013). Registros notables de mamíferos para Campeche, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana 29: 269-286.

INE. (1997). Programa de manejo del Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna “Laguna de Términos”. 1ª ed. Coord. de Publicaciones y Participación Social del INE.

INECC. (2013). Instituto Nacional de Ecología y Cambio Climático, Glosario. April 02, 2017. http://www.inecc.gob.mx/con-eco-biodiversidad/363-coneco-glosario

INEGI. (2016). Encuesta intercensal: Principales resultados de le encuesta intercensal 2015. Campeche, México.

Jiménez-Domínguez, D., Olivera-Gómez, L.D. (2018). Abundancia de la nutria de río en tres sitios de la Reserva de la Biósfera de Pantanos de Centla, con apuntes sobre sus presas. In: Memorias XXXVI Reunión internacional para el estudio de mamíferos marinos. Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco. Villahermosa, Tabasco, México, May 27 – 31, 2018.

Kruuk, H. (2006). Otters: ecology, behaviour and conservation. Oxford University Press Inc. Nueva York, EE.UU.

Macías-Sánchez, S. (2003). Evaluación del hábitat de la nutria neotropical de río (Lontra longicaudis Olfers, 1818) en dos ríos de la zona centro del estado de Veracruz, México. Master's thesis. Instituto de Ecología, A. C. Xalapa, México.

Macías-Sánchez, S., Aranda, M. (1999). Análisis de la alimentación de la nutria neotropical de río Lontra longicaudis (Mammalia: Carnívora) en el sector del río Los Pescados, Veracruz, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana 76: 49-57.

Macías-Sánchez, S., Hernández, A. (2007). Distribución y abundancia de la nutria neotropical, Lontra longicaudis en el río Santiago, Nayarit, México. Mesoamericana 11(3): 93.

Mariano-Mendoza, V.G. (2019). Aspectos ecológicos de la nutria de río (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897) en la laguna “La Lagartera”, Campeche. Bachelor's thesis, FCN-UNACAR. Cd. del Carmen, Campeche, México.

Martínez-Gallardo, R., Sánchez-Cordero, V. (1997). Lista de mamíferos Terrestres. In: González, S.E., Dirzo, R., Vogt, R. C. (Eds.), Historia Natural de Los Tuxtlas, México. Instituto de Biología Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México, pp. 625-628.

Mayagoitia-González P.E., Fierro-Cabo, A., Valdez, R., Andersen, M., Cowley, D., Steiner, R. (2013). Uso de hábitat y perspectivas de Lontra longicaudis en un área protegida de Tamaulipas, México. Revista Therya 4: 243-256.

Morales, M.J.E., Villa, J.T. C. (1998). Notas sobre el uso de la fauna silvestre en Catemaco, Veracruz México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana 73: 127-144.

Orozco-Meyer, A. (1998). Tendencia de la distribución y abundancia de la nutria de río (Lontra longicaudis annectens, Major 1897) en la ribera del río Hondo, Quintana Roo, México. Bachelor's thesis. Instituto Tecnológico de Chetumal, México.

Pardini, R., Trajano, E. (1999). Use of shelters by the neotropical river otter (Lontra longicaudis) in an Atlantic forest stream, southeastern Brazil. J. Mamm. 80: 600-610.

Pat-Fernández, L.A., Calderón-Gómez, G. (2012). Caracterización del perfil turístico en un destino emergente, caso de estudio de ciudad del Carmen, Campeche, México. Gestión Turística 18: 47-70.

Plan Estatal de Desarrollo 2015-2011. Gobierno del estado de Campeche. October 06, 2019. www.campeche.gob.mx/ped2015-2021

Ramírez-Bravo, O.E. (2010). Neotropical Otter (Lontra longicaudis) records in Puebla, Central Mexico. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 27: 134-136.

Ramírez-Pulido. J., Britton, M.C., Perdomo, A., Castro, A. (1986). Guía de los mamíferos de México. Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Iztapalapa, México.

Ramón, C.J. (2000). Hábitos alimentarios de la nutria o perro de agua (Lutra longicaudis, Major) en una fracción del río San Cipriano del Municipio de Nacajuca, Tabasco, México. Bachelor's thesis. Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco, Villahermosa, Tabasco, México.

Ramos-Miranda, J., Flores-Hernández, D., Ayala-Pérez, L.A., Rendón-von Osten, J., Villalobos-Zapata, G., Sosa-López, A. (2006). Átlas hidrológico e ictiológico de la laguna de Términos. Universidad Autónoma de Campeche. San Francisco de Campeche, Campeche, México.

Ramos-Rosas, N.N., Valdespino, C., García-Hernández, J., Gallo-Reynoso, J.P., Olguín, E.J. (2013). Heavy metals in the habitat and throughout the food chain in the Neotropical otter, Lontra longicaudis, in protected Mexican wetlands. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 18: 1163-1173.

Rangel-Aguilar, O. (2008). Abundancia relativa de la nutria y caracterización del hábitat de la nutria de río neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major 1897), en el sector sur del río Yaqui, Sonora, México. In: Memorias del IX Congreso Nacional de Mastozoología, Autlán, Jalisco. September 22 – 26, 2008.

Rangel-Aguilar, O., Gallo-Reynoso, J.P. (2013). Hábitos alimentarios de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en el Río Bavispe-Yaqui, Sonora, México. Revista Therya 4: 297-310.

Rheingantz, M.L., Trinca, C.S. (2015). Lontra longicaudis. Lista roja de la UICN de Especies Amenazadas 2015. November 06, 2018. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/12304/ 21937379#assessment-information

Ruiz-Betancourt, D. (1992). Contribución al conocimiento de algunos aspectos de la biología de la nutria tropical o perro de agua (Lutra longicaudis annectens Mayor 1897) en un trayecto en el Lago de Catemaco, Veracruz, México. Bachelor's thesis. Universidad Veracruzana, Facultad de Biología, Córdoba, Veracruz, Mexico.

Santiago-Plata, V.M. (2009). Abundancia relativa y hábitos alimenticios de la nutria de río (Lontra longicaudis) en la zona de uso intensivo denominada “La Veleta” en el Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Laguna de Términos, Campeche. Bachelor's thesis. Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco. Villahermosa, Tabasco, Mexico.

Santiago-Plata V.M., Valdez-Leal, J.D., Pacheco-Figueroa, C.J, De la Cruz-Burelo, F., Moguel-Ordoñez, E.J. (2013). Aspectos ecológicos de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en el camino La Veleta en la Laguna de Términos, Campeche, México. Revista Therya 4: 265-280.

Secretaría de Pesca y Acuacultura. (2015). Programa de Pesca y acuacultura 2016-2021. Gobierno del estado de Campeche, México.

SEMARNAT. (2010). Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-ECOL-2010, Protección ambiental-Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres- Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio- Lista de especies en riesgo. Diario Oficial de la Federación (Segunda Sección). pp.1-78, Thursday, December 30. Mexico City, Mexico.

Silva-López, G. (2009). Records for the Neotropical River Otter in landscapes of the Ramsar Site Alvarado Lagoon System, México. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 26: 44-49.

Silva-López, G., Mendoza-López, M.R., Cruz-Sánchez, J.S., García-Barradas, O., López- Suárez, G.A, Abarca-Arenas, L.G., Gutiérrez-Mendieta, F., Martínez-Chacón, A. (2012). A qualitative assessment of Lontra longicaudis annectens aquatic habitats in Alvarado, México. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 29: 70-120.

Soler, A. (2002). Nutrias por todo México. Biodiversitas, Boletín bimestral de la Comisión Nacional para el conocimiento y uso de la Biodiversidad Año 7 (43): 13-15.

Soler-Frost, A.M. (2004). Cambios en la abundancia relativa y dieta de Lontra longicaudis en relación a la perturbación de la Selva Lacandona, Chiapas, México. Bachelor's thesis. Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM, México.

UNEP-WCMC. (2013). UNEP-WCMC Species Database: CITES-Listed Species on the World Wide Web. Agost 15, 2019. http://www.unep-wcmc- apps.org/isdb/CITES/Taxonomy/tax-speciesresult.cfm/isdb/CITES/Taxonomy/tax-speciesresult.cfm?source=animals&displaylangua ge=eng&genus=Lontra&species=longicaudis

Villalobos-Zapata, G.J., Guillén, H.A., Reda, D.A., Zetina, T.R., González, J.M., Cu, E.A.D., Del Ángel, T.O., Borges, S.G.N., Ordoñes, S.J. (2002). Ecología del Paisaje y diagnóstico ambiental del ANP “Laguna de Términos”. Informe Final SISIERRA. Clave P/SISIERRA20000706030.

Yáñez-Arancibia, A., Day, J.W. (1988). Ecology of Coastal Ecosystems in the Southern Gulf of Mexico: The Terminos Lagoon Region. Inst. Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, UNAM. Coast. Ecol. Inst. LSU Editorial Universitaria, México.

Yáñez-Arancibia, A., Day, J.W. (2004). Environmental sub-regions in the Gulf of Mexico coastal zone: the ecosystem approach as an integrated management tool. Ocean and Coastal Management 47: 727-757.

Résumé: Connaissance et Perception de la Loutre à Longue Queue (Lontra longicaudis annectens) par les Habitants locaux d’une Réserve Naturelle dans l’État de Campeche au Mexique

La loutre à longue queue est une espèce protégée en vertu de la loi Générale Mexicaine sur la faune sauvage des espèces menacées (NOM-059-ECOL-2010); elle est considérée comme presque menacée sur la Liste rouge de l'IUCN des espèces menacées et reprise à l'Annexe I de la CITES. La loutre à longue queue est mentionnée dans le programme de gestion de la réserve naturelle fédérale de Laguna de Términos mais est rarement mentionnée dans d'autres programmes de gestion des réserves naturelles du Mexique. Comme très peu d'études scientifiques menées dans l'État de Campeche font référence à la loutre à longue queue, nous avons mené une enquête auprès des habitants proches du réseau de la Laguna de Términos afin de connaître leurs avis sur cette espèce. Les données ont été récoltées de juin à octobre 2015 grâce à un questionnaire ad hoc appliqué à 101 habitants locaux. Nous avons posé des questions sur leurs connaissances empiriques de la biologie de la loutre à longue queue et leur perception du statut de l'espèce. Les données ont été résumées en termes de pourcentages et soumises à des analyses statistiques (tests de Kruskal-Wallis) comparatives et interprétatives. Nous avons constaté que les habitants locaux connaissent les loutres à longue queue et ont fourni des informations sincères et cohérentes. Ils ont montré une certaine ambivalence quant à la protection de l'espèce: bien qu'ils aient reconnu l'état de conservation de l'espèce, ils ont également admis que la loutre est parfois exploitée (chassée pour sa fourrure) comme source de revenus. La plupart des personnes interrogées (94-100%) ont soutenu le concept d'un plan de conservation. Ces informations devraient être prises en compte lors de la planification et de la mise en œuvre des activités d'écotourisme dans la réserve naturelle de la Laguna de Términos.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Conocimiento y Percepción de la Nutria Neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) por los Habitantes Locales de un Área Protegida en el Estado de Campeche, México

La nutria neotropical es una especie protegida por la Ley General de Vida Silvestre en la NOM-059-ECOL-2010 y está incluida en la Lista Roja de Especies Amenazadas de la UICN y en el Apéndice I de la CITES. Esta especie se menciona en el Programa de Manejo del Área de Protección Flora y Fauna Laguna de Términos, a diferencia de otros programas de manejo del país en que raramente se menciona. Una exhaustiva revisión bibliográfica para el Estado de Campeche mostró que hay poca investigación de esta especie, por lo que se hizo una encuesta entre los habitantes de las márgenes de la Laguna de Términos. La encuesta recopiló información sobre el conocimiento empírico de los residentes locales sobre la nutria neotropical, así como la percepción sobre su estado actual. La encuesta se aplicó de junio a octubre de 2015 a 101 residentes locales; los resultados se expresaron en términos de porcentajes y se hicieron análisis estadísticos (pruebas de Kruskal-Wallis) para su interpretación. Se encontró que los pobladores conocen ampliamente esta especie y proporcionaron datos verídicos y congruentes. Se detectó una posición ambivalente en cuanto a la protección de la especie, ya reconocen su estatus de conservación, pero ocasionalmente aprovechan la nutria neotropical como recurso (caza por piel). Sin embargo, la gran mayoría (94-100%) de los pobladores están a favor de establecer un plan para su conservación. Es importante considerar esta información al planificar e implementar actividades ecoturísticas dentro del Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Laguna de Términos.

Vuelva a la tapa