IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Citation: Balderas-Mancilla, U. d. J., Reyes-Martínez, P., Vázquez-Maldonado, L.E., Gallo-Reynoso, J.P., Medrano-Walt, M.de los Á., Azuara-Domínguez, A., Vilchis- Juárez, J.E., and Cervantes-Vázquez, M.L. (2023). Knowledge and Perception of the Neotropical Otter (Lontra longicaudis annectens) among Fishermen in the Champayán Lagoon System, Altamira, Tamaulipas, Mexico IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 40 (3): 117 - 130

Knowledge and Perception of the Neotropical Otter (Lontra longicaudis annectens) among Fishermen in the Champayán Lagoon System, Altamira, Tamaulipas, Mexico

Ulises De Jesús Balderas-Mancilla1, Patricia Reyes-Martínez2, Laura Elena Vázquez-Maldonado3*, Juan Pablo Gallo-Reynoso4, María de los Ángeles Medrano-Walt2, Ausencio Azuara-Domínguez1, Juan Ernesto Vilchis- Juárez2, and Martha Laura Cervantes-Vázquez2

1Instituto Tecnológico de Ciudad Victoria, División de Estudios de Posgrado e Investigación. Boulevard Emilio Portes Gil #1301 Pte. A.P. 175 C.P. 87010 Cd. Victoria, Tamaulipas, México

2Instituto Tecnológico de Altamira, Carretera Tampico -Mante, Km 24.5 C.P. 89600, Altamira, Tamaulipas, México

3Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Campus III, Universidad Autónoma del Carmen. Av. Central S/N Esq. con Fracc. Mundo Maya, Cd. del Carmen 24115, Campeche, México

4Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo A.C., Unidad Guaymas. Carretera al Varadero Nacional km 6.6, Las Playitas, 85480 Guaymas, Sonora, México.

*Correspondance Email: lauvamaster@gmail.com

Received 3rd August 2022, accepted 26th March 2023

Abstract: Not enough research has been conducted on the distribution and population density of the Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis annectens) in the state of Tamaulipas. Today, the inhabitants of villages near the Champayán Lagoon System have empirical knowledge of the biodiversity in adjacent areas from experiences in their daily activities. A study was conducted through 35 interviews about the knowledge and perception of the Neotropical otter applied in seven fishermen villages in the Champayán Lagoon System, Altamira, Tamaulipas. Interviews revealed that all of the interviewed fishermen reported knowing the Neotropical otter and having observed it at different spots across the lagoon system. It is reported that the otter is a social species that has been observed in pairs and with offspring. Fishermen mention that otters feed mainly on native and exotic fish and others preys as well as crustaceans, reptiles, and poultry. There is an interaction between fishermen and otters, where the latter steals fish from fishing nets; however, this does not represent an economic loss for fishermen. The 91.4% of fishermen interviewed reported having directly interacted with an otter, and 97.1% mentioned that they had never threatened or disturbed an otter, since they consider it a charismatic species. Only 5.7% mention the otter as a species of great importance for the lagoon system. This work highlighted the need to continue this research applying ethnobiology methodologies to work with local communities, as a first strategy to promote the conservation of the Neotropical otter and to carry out to long-term studies on the interaction of fishermen with otters when their populations may be threatened.

Keywords: Ethnobiology, Fishermen, Neotropical otter, Perception

INTRODUCTION

The Neotropical otter, Lontra longicaudis annectens (Major, 1897), is a semi-aquatic mammal belonging to the family Mustelidae (Gallo-Reynoso, 1989; De Almeida and Ramos Pereira, 2017; Rheingantz et al., 2017) that is closely linked to freshwater (Gallo-Reynoso,1989) and associated marine environments such as lakes, rivers, swamps, coastal islands, and lagoons located in dry and wet forests (Carvalho-Junior et al., 2012).

In Mexico, the subfamily Lutrinae comprises three species: “sea otter” (Enhydra lutris Linnaeus, 1758), “North American river otter or Nearctic otter” (Lontra canadensis Scheber, 1776), and “Neotropical river otter” or “long-tailed otter” (Lontra longicaudis annectens (Major, 1897) (Gallo-Reynoso and Casariego, 2005; Gallo Reynoso et al., 2019); the latter is widely distributed in the Americas, from northwest Mexico to South America (Gallo-Reynoso, 1989; De Almeida and Ramos Pereira, 2017; Rheingantz et al., 2017). In Mexico, this species is distributed from southern Tamaulipas bordering the Gulf of Mexico and part of the Mexican Caribbean in the Atlantic slope, and from the northern parts of Chihuahua and Sonora to the border with Guatemala on the Pacific slope (Gallo-Reynoso, 1997; Aranda, 2000).

The Neotropical otter is listed in the Near-Threatened category on the Red List of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (Rheingantz et al., 2021), as Endangered of Extinction in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES, 2021), and as Threatened in the Mexican Official Standard NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (SEMARNAT, 2010). To increase the knowledge and to contribute to L. longicaudis conservation is essential to conduct studies to determine the current distribution and human perceptions of Neotropical otter (Gallo-Reynoso, 1989, 1996, 2008; Macías-Sánchez and Aranda, 1999).

The lower part of the Guayalejo–Tamesí River basin in Tamaulipas forms a lagoon system of great hydrological, ecological, and social importance in the southern region of the state (Vera, 2004). This area is characterized by high availability of fishes, vegetation, and shelter (logs, roots), which make a suitable habitat for the Neotropical otter (Mayagoitia-González et al., 2013).

Ethno-biological studies have shown that local human populations possess a deep knowledge of the natural resources, including biological resources used by them or with which they interact (Souto et al., 2011; Alves and Rosa, 2013). These local populations are frequently involved in biodiversity monitoring (Harvey et al., 2003; Mejía-Correa, 2014), also called participatory monitoring (Evans and Guariguata, 2008) and could be the first step to integer natural resources political management with conservation strategies (Braga and Schiavetii, 2013). Some works have led to this type of study on the Neotropical otter, for example, Gallo-Reynoso (1989) conducted interviews with inhabitants of Sierra Madre del Sur to know about some aspects related to Neotropical otters. Macías-Sánchez (2003) also used interviews in adults and children to know about the relationship between humans and otters, and their biological and ecological aspects in central Veracruz, México. Vázquez-Maldonado et al. (2021) also conducted interviews with inhabitants of the Laguna de Términos, to find out the perception of the species in the area. These interviews with fishermen may be the first step to know about the relationships with the Neotropical otter in the Champayán Lagoon System. Local people have extensive knowledge of the natural environment and that is a potential habitat for the Neotropical otter. The lack of studies in the southern part of the state has made it impossible to know the role of the species in the ecosystem.

We conducted a study based on semi-structured interviews with fishermen living in villages located adjacent to the Champayán Lagoon System in the municipality of Altamira, Tamaulipas, with the aim to collect information on the knowledge and perception of local inhabitants about the biological and ecological aspects of the Neotropical otter, as well as on the distribution of the species in this area and its interaction with fishermen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

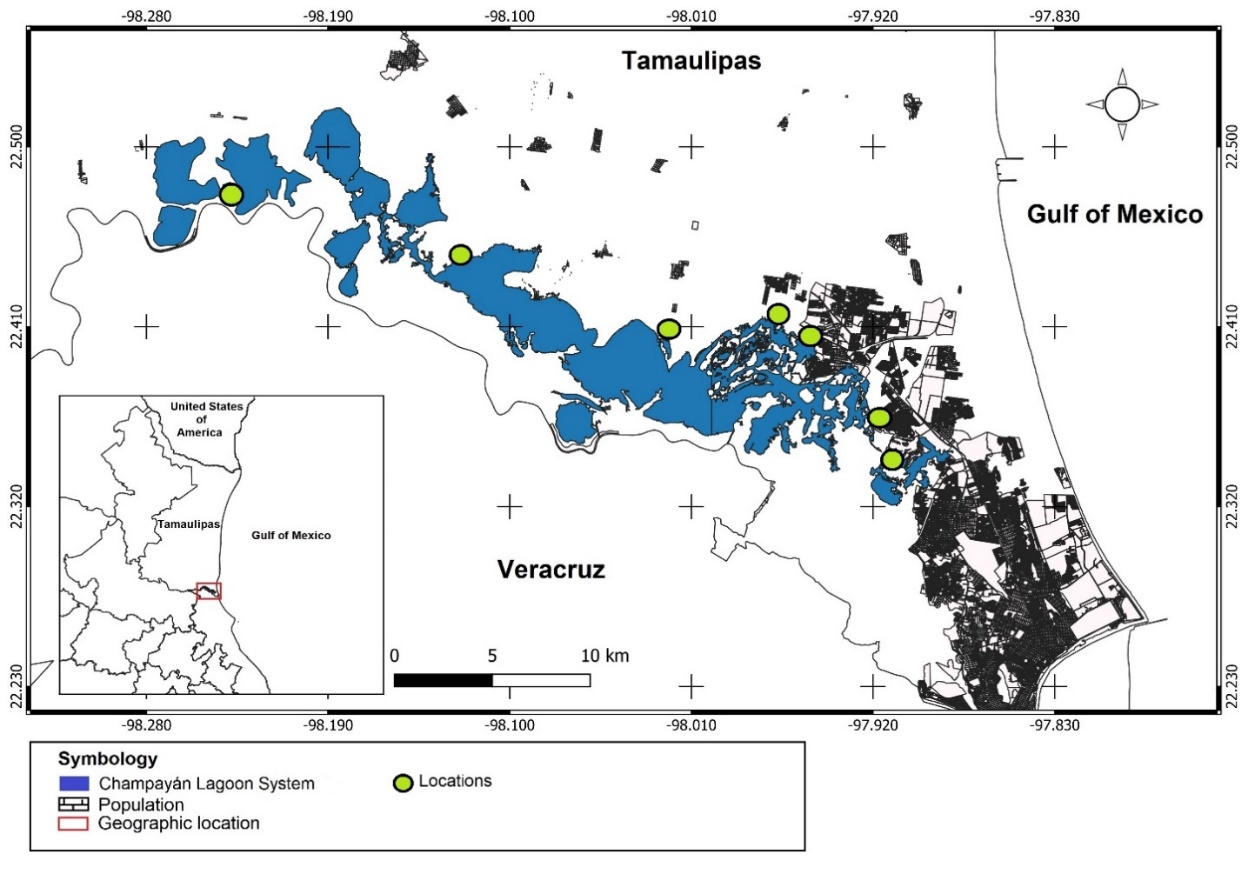

The Champayán Lagoon System is a freshwater body fed by the Guayalejo-Tamesi River with an area of approximately 213 km², a length of 38.4 km, and an average width of 5.6 km. The average depth recorded in the 2013-2016 surveys was 1.5 m, with a maximum depth of 5.9 m. The Champayán Lagoon System holds abundant vegetation (CONAGUA, 2012). This complex hydraulic network is used as a means of communication by fishing populations (Rolón-Aguilar et al., 2015). It also is the main source of water for domestic and industrial uses in the regional urban areas of Altamira, Ciudad Madero, and Tampico municipalities (Fig. 1; SEDUMA, 2015). The local wetland vegetation consists mainly of the southern cattail Typha domingensis that grows in the lagoon banks, and a transition area covered by the shrub Mimosa pigra; both species are also found in islets within the lagoons. Ceratophyllum demersum is a submerged aquatic species also present, along with extensive areas covered by populations of water hyacinth Pontederia crassipes and a narrow strip of riparian vegetation. These banks also harbor patches of trees including Humboldt’s willow Salix humboldtiana, ahuehuete Taxodium mucronatum, rosy trumpet tree Tabebuia rosea, ceiba Ceiba pentandra, and ear pod tree Enterolobium cyclocarpum (CONAGUA, 2012).

Dredging operations in the channels and the lagoon are regularly conducted to maintain an optimal water level at the entrance of the Altamira water treatment plants (Ulloa et al., 2018). The environmental services provided by this lagoon system to society include direct benefits such as the supply of drinking water and food through aquaculture and fisheries, and other services such as recreational activities (SEDUMA, 2015; Ulloa et al., 2018).

The predominant climate is warm sub-humid with rainfall in summer. The mean annual temperature exceeds 22 °C throughout the year; the highest temperatures are recorded from May to September, ranging between 25 °C and 28 °C, and occasionally exceeding 40 °C. The rainy season usually occurs from June to October, with an annual average of 1,043 mm. September is the rainiest month with an average of 250 mm, and the driest season spans from November to May. January and February are the driest months with an average of 21.1 mm and 28.0 mm respectively. These temperature and precipitation conditions produce a warm and humid summer and a dry and cold winter (SEDUMA, 2015).

Data collection and analysis

Thirty-five interviews were conducted in different locations around the Champayán Lagoon System in Altamira, Tamaulipas, during November and December 2020 (Table 1).

The interviews, data gathering, and fieldwork took place over 31 kilometers on the margins of the lagoon. Semi-structured interviews and informal talks were conducted with fishermen, mainly involving adult men and women living in villages along the lagoon. Interviews were based on the questionnaire arranged by Gallo-Reynoso (1989) and Macías-Sánchez (2003) to gather information on the knowledge and perception of respondents about the Neotropical otter in the Sierra Madre del Sur and the central zone of Veracruz, respectively. The interview consisted of 38 questions organized into four sections: 1. General information of the respondent (sex, age, education level, and socioeconomic status); 2. Respondent’s expertise as a fisherman in the area, so that they gain confidence with us and provide reliable information about otters; 3. Biological and ecological aspects of the otter; and 4. Threats, regulations, and conservation of the species.

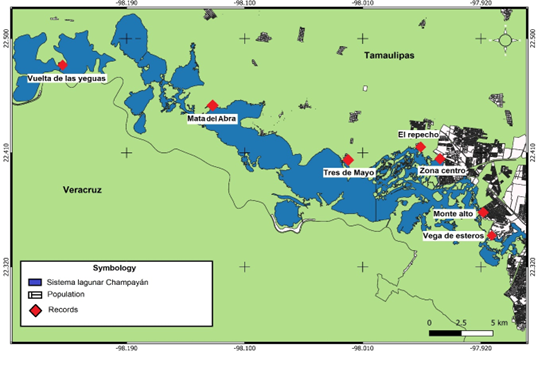

The data gathered from interviewed fishermen were qualitatively processed for analysis, we classified the answers according to the interview sections and presented the percentages obtained respectively. Additionally, we made a map with the distribution of the Neotropical otter in the Champayán Lagoon System based on the information from interviews in each locality.

RESULTS

The people interviewed (n=35) were between 30 and 60 years old and had lived in the area for more than 10 years. In six localities: Vega de Esteros, Monte Alto, Zona Centro, El Repecho, Tres de Mayo, and Mata del Abra, an 80% (n=28) of the interviewed persons were male. In a single town, Vuelta de las Yeguas, a 20% (n=7) of the respondents were female. Their responses evidenced that interviewed people were familiar and have had direct encounters with Neotropical otters. Fishing is the main economic activity for all the interviewed people, either full-time or on a seasonal basis, this activity has given them the opportunity to gain knowledge about the Neotropical otter, locally known as “perro de agua” (“aquatic dog”).

Distribution of the Neotropical otter

All the respondents mentioned that the Neotropical otter is distributed throughout the Champayán Lagoon System, from Vega de Esteros to Vuelta de las Yeguas. Most otters have been sighted in the canals that crosses vegetation patches and that connect with the Tamesí River, which are used for trading between villages. The localities El Repecho, Tres de Mayo, and Mata del Abra have reported a lower frequency of otter sightings, while sightings of Neotropical otters are more frequent in Vega de Esteros, Monte Alto, Zona Centro, and Vuelta de las Yeguas (Fig. 2).

Feeding Habits

94.2% (n=33) of respondents mention that they observed otter feeding preferentially on introduced fish such as tilapia (Oreochromis spp.) and carp (Cyprinus carpio), which are considered the major components of its diet in the area. The respondents observed otters stealing fish trapped in fishing nets and related observations of fish with otter bite marks. As a second food source, 17.1% (n= 6) of respondents mentioned the black bass (Micropterus salmoides) and the pearl scale cichlid or lowland cichlid (Herichthys carpintis).

Only 14.2% (n=5) of the surveyed fishermen mention the consumption of other taxa in the diet of the Neotropical otter, such as prawns, turtle eggs, and poultry. These records come from direct observations by fishermen on otters preying on and consuming wild and domestic animals. The respondents mentioned that domestic animals are easy prey for otters because there are poultry hatcheries in houses near the lagoon shores. Also, 17.1% (n=6) of the fishermen describe the crocodile (Crocodylus moreletii) as a potential predator of the Neotropical otter, and one of them described that there are currently less otters and more crocodiles, while the otters were dominant years ago.

Reproductive Behavior

The 28.5% (n=10) of the respondents mentioned that the breeding season of the Neotropical otter occurs in spring and summer, the interviewed fishermen had observed adult females with offspring in those seasons, and also by the sounds produced by offspring, that are they listen among aquatic vegetation. Regarding the number of offspring per female, 2.8% (n=1) of fishermen have observed an adult female accompanied by four to five pups; 5.7% (n=2), with three to four young; 11.4% (n=4), with two young; and 2.8% (n=1), with a single pup. The fishermen, describe otters as aggressive animals during the breeding season, mainly when boats come very close to their dens. Two fishermen mentioned that an otter nearly attacked them, and another described that an otter climbed onto their boat to attack him.

Activity and Sighting Frequency

Neotropical otters are most frequently observed by the 62.8% (n=22) of the fishermen, during spring, summer, and part of autumn (April to October), when the water level in the lagoon system is high and fish abundance increases, they also mention that otters are observed mainly when more fish are available in the lagoon. Otters can be seen all year round as 31.4% (n=11) of fishermen commented, and being less frequently observed in winter, as only 2.8% (n=1) mention otter sightings in winter.

However, 91.4% (n= 32) of otter records are related to direct sightings of otters swimming, feeding, or interacting with fishermen in the proximity of boats; only 8.5% (n= 3) of the interviewed fishermen have observed spraints among aquatic vegetation on floating islets.

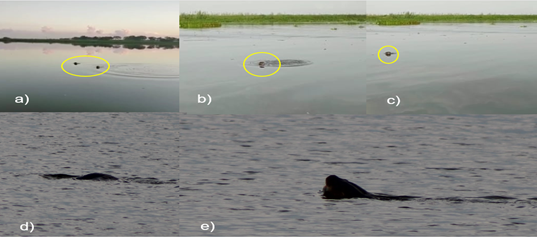

Regarding the activity period of otters, 88.5% (n=31) interviewed fishermen mentioned that Neotropical otters are most active in the morning and in the afternoon, with the greatest activity observed in the early morning hours (07:00 to 09:00 h), while others 11.4% (n=4) comment that otters are active until noon. Literature reports describe that the Neotropical otter is active during twilight hours, feeding mainly in the afternoon. Regarding direct observations, 54.2% (n=19) of fishermen reported having observed otters stealing fish from fishing gear placed by them. Other reported activities of otters include swimming and diving 40.0% (n=14), with the head slightly protruding above the water surface and then immersing in search for food. Other fishermen 5.7% (n=2) reported having interacted with otters swimming on one side of their boats (Fig. 3).

Group Composition, Habitat, and Indirect Evidence

Fishermen interviewed describe otters as social animals frequently observed in groups of two or three individuals, with occasional observations of solitary individuals. However, 57.1% (n=20) of fishermen have frequently observed otters in pairs, describing them as “couples”. Fishermen in the Champayán Lagoon System describe that the Neotropical otter prefers to swim in water 1 m to 2 m deep, and the lagoon maintains this depth level most of the year. Sightings of otters become less frequent in the dry season when the water level is below 1 m depth. This might be due to the fact that there are fewer fish available for both, fishermen and otters; an alternative explanation is that boats cannot go fishing because the water level is too shallow, thus there are fewer observations of otters.

Otters had been rarely seen on the lagoon banks, as described by 91.4% (n=32) of the fishermen, they also say that otters prefer floating islets of vegetation (named cabezales by fishermen). These floating islets include plants such as the cattail (Typha domingensis), reed (Phragmites australis), and water hyacinth (Pontederia crassipes), forming networks of islets interconnected through channels. The 5.7% (n=2) fishermen stated that otters have dens and breeding nests in these sites. Dens are described as structures built between cattail plants, formed by stems, and bent branches to which otters can access through underwater tunnels. Fishermen have observed traces of otter spraints on the vegetation in floating islets, and only one fisherman mentioned otter spraints on the shore of the lagoon system.

Anthropogenic Threats

The relationship between Neotropical otters and fishermen is unavoidable since both feed on almost the same resources. Otters tend to forage for food in easily accessible sources, in this case, fish caught by fishing gear and nets set by fishermen. A 5.7% (n=2) said that occasionally, this has caused the death of some otters when they get entangled in the net. A fisherman mentioned the sale of a young otter, but this was an isolated case that has not been reported again. The 97.1% (n=34) of fishermen stated that they have never threatened or disturbed otters and, conversely, they protect both otters and their environment.

Importance and Conservation

Concerning its ecological importance, 8.5% (n=3) of fishermen highlighted its relevance as a predator living in its natural habitat. Fishermen also mentioned not having hunted otters; on the contrary, when coming across a nearby otter, they only watch it because they stand out for being charismatic organisms. Indeed, 40% (n=14) of the interviewed fishermen indicate that when otters are spotted stealing fish from fishing gear, they just scare them away. Only 5.7% (n=2) of the respondents mentioned being aware of regulations protecting the Neotropical otter; the vast majority are not familiar with any protection measures but are convinced that killing otters is detrimental to the environment.

DISCUSSION

Interactions between humans and otters are well known at all seven fishing locations and have not been documented before. This turns out to be crucial information for designing an efficient effort to conserve the otters in the Champayán Lagoon System. Otters are threatened according to the official norm NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (SEMARNAT, 2010), and in international laws, almost threatened, according to the International Union for Nature Conservation (Rheingantz et al., 2021). In Appendix I of the International Convention on Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES, 2021), they are classed as threatened. This study sought knowledge about, perception of, and experiences of fishermen with Neotropical otters, especially in regard to daily fishing.

The presence of otters is well documented in the southern part of Tamaulipas (Gallo-Reynoso, 1997), the latest records are found in Vega Escondida, recently named a protected natural area in Tampico City (Mayagoitia-González et al., 2013), including the body of water near to Champayán Lagoon System. Fishermen mention the presence of otters to the north and south of the Champayán Lagoon System, their presence in the south of Tamaulipas could be influenced by riparian vegetation cover (CONAGUA, 2012; Mayagoitia-González et al., 2013), as well as the availability of refuge and food, and fish with a length from 0-20 cm that are more available in channels that connect the lagoons with the Tamesí River, where commercial fishing is great (Mayagoitia-González et al., 2013) as well in the trade water-way between localities (Rolón-Aguilar et al., 2015).

Neotropical otter feeding habits from Neotropical otter sprain analyzes in the Champayán Lagoon System are based on exotic (commercial) and native fish, and various other taxa (mollusks, crustaceans, insects, amphibians, birds, and mammals), this is similar to the results found by Rangel-Aguilar and Gallo-Reynoso (2013), Carvalho-Junior et al. (2013), Grajales-García et al. (2019) and Vázquez- Maldonado and Delgado-Estrella (2022). In the Champayán Lagoon System and other water bodies in southern Tamaulipas, the swamp crocodile (Crocodylus moreletii) is an important player inside the ecosystem (Cedillo-Leal et al., 2011), and is probably a predator of Neotropical otter, due to an overpopulation of crocodiles and a decline in the otter population according to the fishermen interviewed.

The reproductive season of Neotropical otters is associated with otter territoriality as mentioned by fishermen: spring and summer (dry season) is when they observe reproductive behavior, according to Gallo-Reynoso (1989). Winter and Spring are the reproductive seasons with higher birth rates, due to the lower river water, but it can occur at any time of the year (Parera, 1996). Interviewed people mention that the number of pups is variable, with sightings of one to five pups, two pups being the most common. Larivière (1999) affirms that two to three pups is usual for the species, although it can be from one to five pups, and usually is two pups (Reid, 1997).

The highest frequency of direct otter sightings was highly associated with fish abundance and availability to both fishermen and otters, occurring in spring, summer and fall. And less frequent during winter. Fishermen rarely observe spraints (Santiago-Plata et al., 2013) by the dirt road to La Veleta, in Campeche State, but report more frequent footprints and sightings during the rainy season (June-October) than in the dry season (March-May), which contrasts with the observations reported by González-Christen et al. (2013) in the Catemaco Lagoon, Veracruz State, where the abundance of otter’s records increases after the rainy season at the beginning of the dry season (November to January).Similarly, Duque-Dávila et al. (2013) reported a higher number of otters in the dry season and a lower number in the rainy season in Río Grande, Biosphere Reserve of Tehuacán-Cuicatlán, Oaxaca State.

The daily activity of the otters and the activity of the fishermen coincide early in the morning (07:00-09:00 am). It is known that the Neotropical otter displays crepuscular habits, having greater foraging activity at dusk and dawn. However, it is known to adopt more nocturnal habits in areas with greater human activity (Wilson and Mittermeier, 2009; Rheingantz et al., 2016; Gallo-Reynoso et al., 2019).

Otters are described as elusive and social animal by fishermen, with groups of one to three individuals, two being the most common. This coincides with that described by Aranda (2000), where the behavior of the Neotropical otter is described as mainly solitary, but it can be observed in pairs and in family groups. Orozco (1998) records that 64% of the otters seen in Río Hondo, Quintana Roo were solitary; Vázquez-Maldonado et al. (2021) in Laguna de Términos Campeche, reported that 56 to 73% of sightings were of solitary individuals, although groups of two and three individuals have been observed, mostly females with cubs. Localities such as Atasta (79%) and Palizada (62%) are the places where groups have been observed most frequently.

Fishermen report that vegetation has an important influence on the behavior and daily life of the species, floating islands being used as shelter sites dens; they are mainly composed of herbaceous plants, bushes and aquatic plants with riparian and aquatic vegetation prevailing (CONAGUA, 2012). This agrees with the findings of several authors in which the presence of otter is highly associated with vegetation cover (García and Quintana, 2005; Arellano-Nicolás et al., 2012); such habitat is composed of dense forests, rapid flow of water and associated riparian vegetation in lentic environments (Aceituno et al., 2015).

Regarding human - otter conflict, the information collected suggests that these events are isolated and sporadic, and there is no major threat to the otters. Fish stealing from nets is a behavior that does not cause any large economic loses according to several fishermen. This might be due to the increase in availability of prey in areas where there are human activities; nevertheless, a bad perception of the otter’s presence might in future generate conflict between fishermen and otters (Hernández-Romero et al., 2018). Such interactions should be thoroughly evaluated with long term studies when the otter populations might be threatened (Andrade et al., 2019).

Hernández-Romero et al. (2018) describe a conflict between trout farmers and Neotropical otters in Tonalaco, Veracruz, where a negative perception of otters has caused hunting to eliminate the threat to their fish. Barbieri et al. (2012) analyzed the perception of otters in two fishing localities in Brazil: in Tramandaí, the fishing activities affected were less, while in Imbé, where the effect of otters on fish is greater, the fishermen had a greater negative perception about otters.

Otters are not generally seen as a problematic species for fisherman in the Champayán Lagoon System, since otters are a charismatic species. A large number of interviewed persons showed a positive attitude towards the existence of laws that protect otters. We also detected some ecological awareness: when we asked for some reasons to protect otters, a large majority highlighted their importance as predators and that they are part of the environment. The fishing communities in the Champayán Lagoon System have extensive empirical knowledge of the surrounding environment, which is a potential habitat for otters. Based on this type of knowledge, there are multiple ethno-biological studies in other parts of the world carried out with fishermen and their contact with a wide a range of organisms (Begossi et al., 2016). In developing countries, where there is a great need for data and resources, collecting empirical local ecological knowledge to expand our understanding of the environment has been a relevant issue (Berkström et al., 2019) and the use of tools such as interviews and questionnaires have been used to assess possible damage and loss of biodiversity related to species under some degree of threat. This can represent a first step to integrate political management of natural resources and conservation strategies together with the response from local communities (Braga and Schiavetii, 2013).

CONCLUSIONS

The Neotropical otter is a well-known species to fishermen in all fishing localities of the Champayán Lagoon System, Altamira, Tamaulipas, where it is distributed through most of the lagoon complex; there is, however, a lack of knowledge about the status of its population. Sightings were reported at all surveyed locations, and respondents described frequent interactions between fishermen and otters. Otters have been observed to feed on fish caught in fishing nets, this being their main source of food; apparently, this behavior was been developed by otters a long time ago. The fishermen mentioned that this feeding behavior of the otters does not cause problems for their fishing activities, and their presence does not generate economic losses. However, it can be dangerous for otters, as they occasionally become entangled in the nets and die. Otter sightings have been incidental as fishermen carry out their activities; however, they mentioned that these sightings have become less and less frequent in this lagoon system. The fishermen have a deep empirical knowledge about the biological and ecological aspects of the Neotropical otter, describing it as a friendly species that does not represent any danger to them. Consequently, they try to protect it and know that otters are an important element of the lagoon´s ecosystem.

Acknowledgements: We deeply thank all respondents from the different locations for the valuable information provided. María Elena Sánchez-Salazar translated the manuscript into English.

REFERENCES

Aceituno, F, Trochez, D, and Nuñez, C (2015). Recent Record of the Neotropical River Otter (Lontra longicaudis) in the Choluteca River Tegucigalpa, Honduras. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 32 (1): 25 – 29. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume32/Aceituno_et_al_2015.html

Alves, R.R.N. and Rosa, L.L. (2013). Animals in Traditional Folk Medicine: Implications for Conservation. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, Berlin. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-29026-8

Andrade, A.M., Arcoverde, D.L. , and Albernaz, A.L. (2019). Relationship of Neotropical otter vestiges with environmental and anthropogenic factors. Acta Amazonica, 49: 183-192. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-4392201801122

Aranda, S.M. (2000). Huellas y otros rastros de los mamíferos grandes y medianos de México. Instituto de Ecología, A. C., Xalapa, México. ISBN 9789687863627

Arellano-Nicolás, E., Sánchez, E. , and Mosqueda, M.A. (2012). Distribución y abundancia de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en Tlacotalpan, Veracruz, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (n.s.) 28: 270-279. https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0065-17372012000200002

Barbieri, F., Machado, R., Zappes, C.A. , and de Oliveira, L.R. (2012). Interactions between the Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis) and gillnet fishery in the southern Brazilian coast. Ocean & Coastal Management. 63:16-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.03.007

Begossi, A., Salivonchyk, S., Lopes, P.F. , and Silvano, R.A. (2016). Fishers’ knowledge on the coast of Brazil. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 12:1-34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-016-0091-1

Berkström, C., Papadopoulos, M., Jiddawi, N. S. , and Nordlund, L.M. (2019). Fishers’ local ecological knowledge (LEK) on connectivity and seascape management. Frontiers in Marine Science. 6: 130. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00130

Braga, H.D.O. , and Schiavetti, A. (2013). Attitudes and local ecological knowledge of experts fishermen in relation to conservation and bycatch of sea turtles (reptilia: testudines), Southern Bahia, Brazil. Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine.9: 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-9-15

Carvalho-Junior, O., Fillipini, A. and Salvador, C. (2012). Distribution of Neotropical Otter, Lontra longicaudis (Olfers, 1818) (Mustelidae) in Coastal Islands of Santa Catarina, Southern Brazil IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 29 (2): 95 - 108 https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume29/Carvalho_et_al_2012.html

Carvalho-Junior, O., Macedo-Soare, L., Bez Birolo, A. and Snyder, T. (2013). A Comparative Diet Analysis of the Neotropical Otter in Santa Catarina Island, Brazil. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 30 (2): 67 - 77 https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume30/Carvalho_et_al_2013.html

Cedillo-Leal, C., Martínez-González, J.C., Briones-Ercinia, F., Cienfuegos-Rivas, E., García-Grajales, M.C. (2011). Importance of the crocodile (Crocodylus moreletii) in the coastal wetlands of Tamaulipas, México. CienciaUat, 21: 18-23. https://revistaciencia.uat.edu.mx/index.php/CienciaUAT/article/view/71

CITES (Convención sobre el Comercio Internacional de Especies Amenazadas de Fauna y Flora Silvestres). (2021). Apéndices I, II y III en vigor a partir del 22 de junio de 2021. https://cites.org/sites/default/files/eng/app/2021/E-Appendices-2021-02-14.pdf

CONAGUA. (2012). Primer informe de validación en campo estero del Tamesí, Tamaulipas. Fondo Sectorial de Investigación y Desarrollo sobre el Agua. Proyecto 84369. CONACyT-CONAGUA. Ciudad Universitaria. https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/102187/Estero_del_Tames_.pdf

De Almeida, L.R., Ramos Pereira, M.J. (2017). Ecology and biogeography of the Neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis: existing knowledge and open questions. Mammal Research. 62: 313-32 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13364-017-0333-1

Duque-Dávila, D.L., Martínez-Ramírez, E., Botello-López, F.J., Sánchez-Cordero, V. (2013). Distribución, abundancia y hábitos alimentarios de la nutria (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897) en el Río Grande, Reserva de la Biosfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán, Oaxaca, México. Therya, 4(2): 281-296. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-13-128

Evans, K., Guariguata, M.R. (2008). Monitoreo participativo para el manejo forestal en el trópico: una revisión de herramientas, conceptos y lecciones aprendidas. Centro para la Investigación Forestal Internacional (CIFOR), Bogor, Indonesia. https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/Books/BGuariguata0801S.pdf

Gallo-Reynoso, J.P. (1989). Distribución y estado actual de la nutria o perro de agua (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897) en la sierra Madre del Sur, México.Master's thesis. Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México, D.F https://repositorio.unam.mx/contenidos/distribucion-y-estado-actual-de-la-nutria-o-perro-de-agua-lutra-longicaudis-annectens-major-1897-en-la-sierra-madre-del-s-90196?c=62D9gD&d=true&q=*:*&i=1&v=1&t=search_0&as=0

Gallo-Reynoso, J.P. (1996). Distribution of neotropical river otter (Lutra longicaudis annectens Major, 1987) in the rio Yaqui, Sonora, México. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin. 13(1):27-31. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume13/Gallo_1996.html

Gallo-Reynoso, J.P. (1997). Situación y distribución de las nutrias en México, con énfasis en Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1987. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología. 2:10-32. https://doi.org/10.22201/ie.20074484e.1997.2.1.70

Gallo-Reynoso, J.P. (2008). Nutria de río. Especies Revista sobre Conservación y Biodiversidad. 24:613.

Gallo-Reynoso, J.P., Casariego, M.A. (2005). Lontra longicaudis (Olfers, 1818). In: Ceballos, G., Oliva G. (Eds.). Los mamíferos silvestres de México. FCE, CONABIO. Ciudad de México, México, pp. 374-376. ISBN: 970-9000-30-6

Gallo-Reynoso, J.P., Macías-Sánchez S., Nuñez-Ramos, V.A., Loya-Jaquez, A., Barba-Acuña, L.D., Guerrero-Flores, J., Ponce-García G., Gardea-Bejar, A.A. (2019). Identity and distribution of the Nearctic otter (Lontra canadensis) at the Rio Conchos Basin, Chihuahua, Mexico. Therya. 10(3):243-253. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-19-894

García, C.M., Quintana, R.D. (2005). Uso de canales deforestación por el lobito de río (Lontra longicaudis) en el bajo delta del Paraná en relación a sus características fisicoquímicas. Poster presentado en las XX Jornadas Argentinas de Mastozoología en noviembre de 2005.

González-Christen, A., Delfín-Alfonso, C.A., Sosa-Martínez, A. (2013). Distribución y abundancia de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897), en el Lago de Catemaco, Veracruz, México. Therya, 4(2): 201-217. https://www.revistas-conacyt.unam.mx/therya/index.php/THERYA/article/view/52

Grajales-García, D., Serrano, A., Capistrán-Barradas, A., Naval-Ávila, C., Pech-Canché, J.M., Becerril-Gómez, C. (2019). Hábitos alimenticios de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) (Carnivora: Mustelidae) en la zona costera de Tuxpan, Veracruz. Revista mexicana de Biodiversidad. 90: e902502. https://doi.org/10.22201/ib.20078706e.2019.90.2502

Harvey, C.A., González, J., Sánchez, V. (2003). ¿Cómo involucrar a la población local en el monitoreo de la biodiversidad? Ideas de Talamanca, Costa Rica. Agroforestería en las Américas. 10: 18-23. https://repositorio.catie.ac.cr/handle/11554/6947

Hernández-Romero, P.C., Botello López, F.J., Hernández García, N., and Espinoza Rodríguez, J. (2018). New Altitudinal Record of Neotropical Otter (Lontra longicaudis Olfers, 1818) and Conflict with Fish Farmers in Mexico. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 35 (4): 193 – 197. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume35/HernandezRomero_et_al_2018.html

Larivière, S. (1999). Lontra longicaudis. Mammalian Species, 609: 1-5. https://doi.org/10.2307/3504393

Macías-Sánchez, S.S. (2003). Evaluación del hábitat de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis Olfers, 1818) En dos ríos de la zona centro del Estado de Veracruz, México. Master's thesis. Instituto de Ecología. A.C. Xalapa. México. https://docplayer.es/46117753-Evaluacion-del-habitat-de-la-nutria-neotropical-lontra-longicaudis-olfers-1818-en-dos-rios-de-la-zona-centro-del-estado-de-veracruz-mexico.html

Macías-Sánchez, S.S., Aranda, M. (1999). Análisis de la alimentación de la nutria neotropical Lontra longicaudis (Mammalia: Carnívora) en el sector del río pescados, Veracruz, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana, 76: 49 - 57. https://biblat.unam.mx/hevila/Actazoologicamexicana/1999/no76/4.pdf

Mayagoitia-González, P.E., Fierro-Cabo, A., Valdez, R., Andersen, M., Cowley, D.,Steiner, R. (2013). Uso de hábitat y perspectivas de Lontra longicaudis en un área protegida de Tamaulipas, México. Therya, 4: 243-256. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-13-130

Mejía-Correa, S. (2014). Monitoreo participativo de mamíferos grandes y medianos en el Parque Nacional Natural Munchique, Colombia. Mesoamericana. 18: 39-53. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277551226_MONITOREO_PARTICIPATIVO_DE_MAMIFEROS_GRANDES_Y_MEDIANOS_EN_EL_PARQUE_NACIONAL_NATURAL_MUNCHIQUE_COLOMBIA

Orozco, M.A. (1998). Tendencia de la distribución y abundancia de la nutria de río (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1987), en la ribera del río Hondo, Quintana Roo, México. Bachelor's thesis. Instituto Tecnológico de Chetumal.

Parera, A. (1996) Las Nutrias Verdaderas de la Argentina. Boletin Técnico de la Fundacion Vida Silvestre Argentina. 21: 1-31.

Rangel-Aguilar, O., Gallo-Reynoso, J.P. (2013). Hábitos alimentarios de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en el río Bavispe-Yaqui, Sonora, México. Therya. 4: 297-309. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-13-135

Reid, F. (1997). A Field guide to the mammals of Central America and Southeast Mexico. Oxford University Press, New York. ISBN: 9780195343236

Rheingantz, M.L., Leuchtenberger, C., Zucco,. C.A., Fernandez, F.A. (2016) Differences in activity patterns of the Neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis between rivers of two Brazilian ecoregions. J Trop Ecol. 32: 170-174. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467416000079

Rheingantz, M.L., Santiago‐Plata, V.M., Trinca, C.S. (2017). The Neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis: a comprehensive update on the current knowledge and conservation status of this semiaquatic carnivore. Mammal Review. 47:291-305. https://doi.org/10.1111/mam.12098

Rheingantz, M.L., Rosas-Ribeiro, P., Gallo-Reynoso, J.P., Fonseca da Silva, V.C., Wallace, R., Utreras, V and Hernández-Romero, P. (2021). Lontra longicaudis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e. T12304A164577708.ICUCN https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T12304A219373698.en

Rolón-Aguilar, J.C., Galván-Vega, E., Pichardo-Ramírez, R., Tobías-Jaramillo, R., Treviño-Trujillo, J., Vargas-Castilleja, R.C. (2015). Análisis de las afectaciones del agua en la Laguna de Champayán como fuente de abastecimiento de agua para el municipio de Altamira, Tamaulipas. In: Rolón-Aguilar, J.C., Cabrera-Cruz, R.B.E., Rolón-Aguilar, E., Pichardo-Ramírez, R., Tobías Jaramillo, R., Treviño-Trujillo, J. (Eds). Investigaciones Actuales en Medioambiente, Tomo II. Science Associated Editors L.L.C., Cheyenne. pp, 101-113. ISBN 978-1-944162-04-7

Santiago-Plata, V.M., Valdez-Leal, J.D., Pacheco-Figueroa C.J., De la Cruz Burelo, F., Moguel-Ordóñez, E.J. (2013). Aspectos ecológicos de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en el camino La Veleta en la Laguna de Términos, Campeche, México. Therya. 4: 265-280. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-13-131

SEDUMA (Secretaría de Desarrollo Urbano y Medio Ambiente De Tamaulipas). (2015). Perspectivas del Ambiente y Cambio Climático en el Medio Urbano: ECCO Zona Conurbada del Sur de Tamaulipas. México: Secretaría de Desarrollo Urbano y Medio Ambiente, Programa de Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente en México. ISBN 978-9978-67-272-3

SEMARNAT (Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recusos Naturales) (2010). Norma Oficial Mexicana Nom-059-Semarnat-2010, Protección ambiental-Especies nativas de México de flora y fauna silvestres-Categorías de riesgo y especificaciones para su inclusión, exclusión o cambio-Lista de especies en riesgo. Diario Oficial de la Federación (Segunda Sección). pp.1-78. https://www.dof.gob.mx/normasOficiales/4254/semarnat/semarnat.htm

Souto, W.M.S., Mourão, J.S., Barboza, R.R.D., Alves, R.R.N. (2011). Parallels between zootherapeutic practices in Ethnoveterinary and Human Complementary Medicine in NE Brazil. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 134: 753-767 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2011.01.041

Ulloa, M., Vargas, R., Rolón, J. (2018). Hacia la evaluación del estado trófico de la Laguna de Champayán en Tamaulipas: condiciones de primavera y otoño 2006-2016. In Investigaciones actuales en medio ambiente I, Pearson Educación de México. Pages 45-52. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320556776_Hacia_la_evaluacion_del_estado_trofico_de_la_Laguna_de_Champayan_en_Tamaulipas_condiciones_de_primavera_y_otono_2006-2016

Vázquez-Maldonad, L., Delgado-Estrella, A. and Gallo-Reynoso, J.P. (2021). Knowledge and Perception of the Neotropical Otter (Lontra longicaudis annectens) by Local Inhabitants of a Protected Area in the State of Campeche, Mexico. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 38 (3): 155 - 172 https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume38/Vasquez-Maldonado_et_al_2021.html

Vázquez-Maldonado, L. E., Delgado-Estrella, A. (2022). Diet of Lontra longicaudis in La Sangría Lagoon, México. Therya Notes, 3: 125-132. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya_notes-22-83

Vera, V.R. (2004). Calidad del agua. La cuenca del río Guayalejo-Tamesí, situación actual, políticas públicas y perspectivas. México: El colegio de Tamaulipas. 75–88. ISBN 9789709860009

Wilson, D.E., Mittermeier, A.R. (2009) Handbook of the mammals of the world: carnivores. Lynx Editions, Barcelona. ISBN 978-8496553491

Résumé: Connaissance et Perception de la Loutre à Longue Queue (Lontra longicaudis annectens) par les Pêcheurs dans le Système Lagunaire de Champayán, Altamira, Tamaulipas, Mexique

La recherche sur la distribution et la densité de population de la loutre à longue queue (Lontra longicaudis annectens) n’est pas assez documentée dans l'état de Tamaulipas. Aujourd'hui, les habitants des villages proches du système lagunaire de Champayán ont une connaissance empirique de la biodiversité dans les zones adjacentes à partir d'expériences dans leurs activités quotidiennes. Une étude comportant 35 entretiens a été menée sur la connaissance et la perception de la loutre à longue queue appliquée à sept villages de pêcheurs du système lagunaire de Champayán, Altamira, Tamaulipas. Les entretiens ont révélé que tous les pêcheurs interrogés ont déclaré connaître la loutre à longue queue et l'avoir observée à différents endroits du système lagunaire. Il est rapporté que la loutre est une espèce sociale qui a été observée en couple et avec sa progéniture. Les pêcheurs mentionnent que les loutres se nourrissent principalement de poissons indigènes et exotiques et d'autres proies ainsi que de crustacés, de reptiles et de volailles. Il existe une interaction entre pêcheurs et loutres, ces dernières volant du poisson dans les filets de pêche ; cependant, cela ne représente pas une perte économique pour les pêcheurs. Certains pêcheurs interrogés (8,5%) ont déclaré avoir interagi directement avec une loutre, et 97,1% mentionnent n'avoir jamais menacé ou dérangé une loutre, car ils la considèrent comme une espèce charismatique. Seuls 5,7% mentionnent la loutre comme une espèce de grande importance pour le système lagunaire. Ce travail a mis en évidence la nécessité de poursuivre cette recherche en appliquant des méthodologies ethno-biologiques visant à travailler avec les communautés locales, comme première stratégie afin de promouvoir la conservation de la loutre à longue queue et de mener à bien des études à long terme sur l'interaction entre pêcheurs et loutres lorsque leurs populations peuvent être menacées..

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Conocimiento y Percepción sobre la Nutria Neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) por Pescadores en el Sistema Lagunar Champayán, Altamira, Tamaulipas, México

Son insuficientes las investigaciones realizadas sobre la distribución y densidad poblacional de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en el estado de Tamaulipas. Actualmente, los habitantes de los poblados cercanos al Sistema Lagunar Champayán poseen un conocimiento empírico de la biodiversidad en las zonas adyacentes a partir de las experiencias vividas en sus actividades cotidianas. En siete poblados de pescadores del Sistema Lagunar Champayán, Altamira, Tamaulipas se realizó un estudio sobre el conocimiento y percepción de la nutria neotropical a través de 35 entrevistas. Las entrevistas revelaron que todos los pescadores encustados conocen a la nutria neotropical y mencionan haberla observado en diferentes puntos del sistema lagunar. Ellos informan que la nutria es una especie social que ha sido observada en parejas y con crías. Los pescadores mencionan que las nutrias se alimentan principalmente de peces nativos y exóticos y de otras presas como de crustáceos, reptiles y aves de corral. Existe una interacción entre pescadores y nutrias, donde estas últimas roban pescado de las redes de pesca; sin embargo, esto no representa una pérdida económica para los pescadores. El 91.4% de los pescadores entrevistados registraron haber interactuado directamente con una nutria, y el 97.1% mencionan que nunca han amenazado o molestado a una nutria, ya que la consideran una especie carismática. Sólo el 5.7% menciona a la nutria como una especie de gran importancia para el sistema lagunar. Este trabajo resaltó la necesidad de continuar esta investigación aplicando metodologías de etnobiología para trabajar con las comunidades locales, como una primera estrategia para promover la conservación de la nutria neotropical y realizar a largo plazo estudios sobre la interacción de los pescadores con las nutrias cuando sus poblaciones puedan estar amenazadas.

Vuelva a la tapa