IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Citation: Leuchtenberger,C., Di Martino, S., Distel,A., Greco, M., Longo, M., and Duplaix, N.(2023). New Confirmed Records of the Giant Otter (Pteronura brasiliensis, Gmelin, 1788) in Argentina. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 40 (3): 131 - 133

New Confirmed Records of the Giant Otter (Pteronura brasiliensis, Gmelin, 1788) in Argentina

Caroline Leuchtenberger1,2*, Sebastián Di Martino3, Augusto Distel3, Matías Greco3, Magalí Longo3, and Nicole Duplaix2

1Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology Farroupilha, Alameda Santiago do Chile, 195 Nossa Sra. das Dores, Santa Maria, RS, Brazil

2IUCN Species Survival Commission, Otter Specialist Group, Mauverney 28, 1196 Gland, Switzerland

3Rewilding Argentina Foundation, Scalabrini Ortiz 3355, Piso 4 Oficina “J”, CP 1425, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina

*Correspondance Email: caroleucht@gmail.com

Received 22nd March 2023, accepted 11th April 2023

Abstract: Here, we report two independent and confirmed observations of solitary giant otters (Pteronura brasiliensis) recorded in December 2021 and September 2022 in Argentina. The former observation, a male first seen in El Impenetrable National Park in May 2021, was recorded in Buenos Aires province, which lies outside the historical distribution known for giant otters. The latter observation, an adult of unknown sex, was recorded in the Iberá Park, Corrientes province, where giant otter vanished more than 30 years ago. These records highlight the urgency for management strategies directed to enhance the recovery of giant otter populations in their historical range.

Keywords:distribution range, Lutrinae, reintroduction, South America, wildlife conservation.

INTRODUCTION

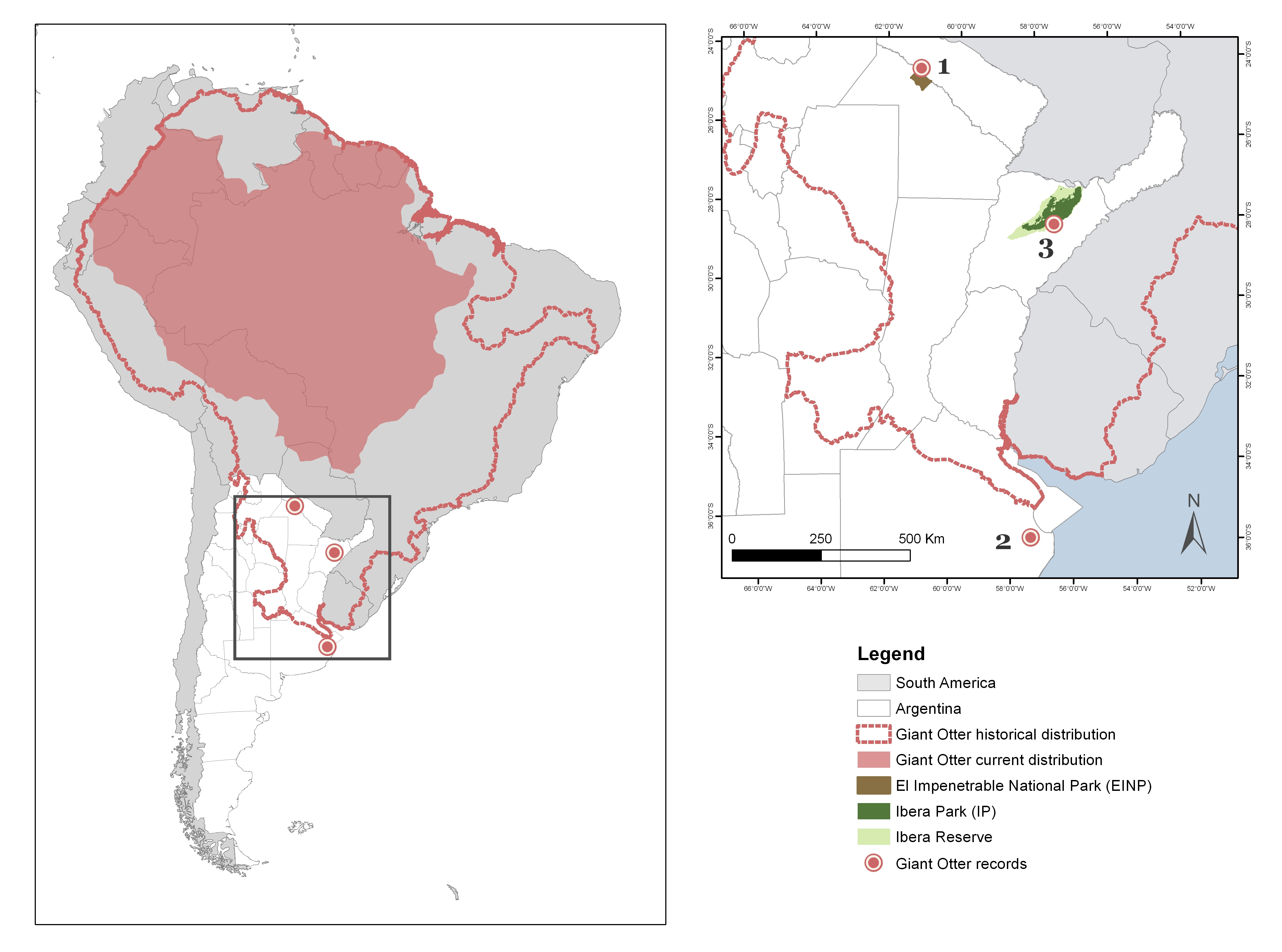

Giant otters (Pteronura brasiliensis) are globally endangered and regionally extinct in Argentina (Di Martino et al., 2019), where the last confirmed record of the species dates from 1986 (Chebez and Bertonatti, 1994). Afterwards and until 2010, a handful of observations, always of solitary individuals, have been reported in the northeastern region of the country but all these records lacked supporting evidence like signs (i.e., tracks and scats) and images. However, in May 2021 an adult male was first observed, then photographed, while swimming in a pond formed by old meanders of the Bermejo River in El Impenetrable National Park (EINP) in the Chaco region (Leuchtenberger et al., 2021). Further monitoring using camera traps found no evidence of other accompanying giant otters. No other report of a giant otter has been published for Argentina since then. Here, we present two new and confirmed observations of solitary giant otters in Argentina.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The first individual was recorded in the Pampas region, Buenos Aires province, near Villa Roch (Fig. 1). Here, land use is characterized by intensive cattle ranching and farming (Fig. 2). Small- to medium-sized lagoons (up to 300 to 400 hectares) and artificial channels, some of which connect with the La Plata River, can be found in the area. At this latitude (-36.2766°S) the La Plata River meets the Atlantic Ocean, resulting in brackish waters. This location lies outside the known historic distribution of the species.

The second individual was recorded in Ibera Park (IP), Corrientes province. This park, a complex of protected areas including the Iberá National Park and the Iberá Provincial Park (both IUCN Category II), encompasses 756,000 ha (Fig. 1) and conserves an extensive wetland characterized by swamps, bogs, lagoons, streams, grasslands, and patches of forests (Fig. 3). This location lies inside the known historic distribution of the species (Beccaceci and Waller, 2000), although giant otters vanished from Corrientes more than 30 years ago (Beccaceci et al., 1995).

RESULTS

The first individual was filmed and photographed with a smartphone by a farmer on December 1st and 2nd 2021, near Villa Roch, a town located in the Buenos Aires province (36.4836°S, 57.4170°W, 4 m above sea level). Photos and videos were sent in November 2022 to one of the authors (SD), who, in January 2023, visited the area and interviewed the farmer. According to the farmer’s account, the giant otter was first seen on Dec 1st 2021 during daylight. This individual was observed first running in the field and then lying down in a small patch of forest, where it stayed until the next day. The farmer speculated that the otter might have reached her property using irrigation canals that drain from the Río de la Plata to her farm.

Subsequent analysis of the otter’s throat marks revealed that they were identical to those observed in the solitary male spotted in May 2021 at EINP and surrounding area (Fig. 4). In November 21st, 2021 fresh signs were observed for the last time in the EINP area (eg. tracks, scats), but we didn’t get any photographic record of the animal. If these signs observed in November, 2021 at EINP correspond to the same solitary male observed in December, 2021 in Villa Roch, then this individual must have travelled over 2000 km, along the Bermejo, Paraná and La Plata rivers and artificial Canal Number 1, in only 10 days. Previous photographic records of this individual, after its first sighting in May 2021 at EINP, suggest that the maximum distance that it may have traveled was 200 km in, at most, 2 days.

The second individual, an adult giant otter of unknown sex (Fig. 5), was photographed on September 2nd, 2022, at 10:40 by one of the 28 camera traps (Browning Strike Force) that we deploy every year in an area of IP. This camera, located in the area known as Eulogio (28.5812°S, 57.2484°W, 88 m above sea level), took, in a period of 6 seconds, four photographs. Following this finding, we increased the number of camera traps in the area. However, we registered neither this nor other individuals to date. Similarly, and despite intensive searches, we found neither tracks nor scats in the location where the giant otter was photographed.

DISCUSSION

Here we presented the southernmost observation of a giant otter ever recorded and the first record for the Buenos Aires province. Moreover, the distance travelled by this individual represented the longest dispersal movement known for the species to date. This observation questions available information about the historical distribution of the species (Di Martino et al., 2019), and forces specialists to increase efforts to understand how early Spanish settlers might have affected southern populations of giant otters.

We also reported a second confirmed record of a giant otter in Argentina within an interval of 16 months (Leuchtenberger et al., 2021) and after 36 years of the last confirmed observation in the country (Chebez and Bertonatti, 1994). Like the individual observed first in EINP and then in Buenos Aires province, the origin of the giant otter photographed in IP is unknown, perhaps a migrant from a population in Paraguay being the most plausible, albeit untested, explanation.

Regardless of their origin, the presence of these individuals in Argentina highlights the importance of (1) establishing protected areas such as EINP and IP to conserve suitable habitat and maintaining corridors for dispersing giant otters from stronghold populations, (2) maintaining and increasing survey efforts to detect isolated individuals and even relict populations and (3) conservation translocation actions, whenever possible, to improve the recovery of the species to its indigenous range. Furthermore, the translocation of isolated individuals to current founding nuclei of giant otters, such as those that are being stablished by the Giant Otter Reintroduction Program at EINP and IP (Zamboni et al., 2018) could reinforce the establishment of a viable population (IUCN/SSC, 2013).

Acknowledgements: To Cipriana Aristegui and Claudia Curi who provided the record of the solitary male in Buenos Aires province. To Viviana Benesovsky who made the map.

REFERENCES

Beccaceci, M. D., and Waller, T. (2000). Presence of the Giant Otter, Pteronura brasiliensis, in the Corrientes Province, Argentina. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull, 17: 31 - 33. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume17/Beccaceci_Waller_2000.html

Beccaceci, M.D., and García Rams, M. (1995). Comentarios sobre la extinción de grandes mamíferos correntinos en la segunda mitad del siglo XX. Resúmenes X Jornadas Argentinas de Mastozoología, pp.6-7. Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos, La Plata, Argentina.

Chebez, J.C., Bertonatti, C. (1994). Los que se van: especies argentinas en peligro. Editorial Albatros. ISBN 978-9502406237

Di Martino, S., Zamboni, T., Valenzuela, A.E.J., and Gil, G. E. (2019). Pteronura brasiliensis. En: SAyDS–SAREM (eds.) Categorización 2019 de los mamíferos de Argentina según su riesgo de extinción. Lista Roja de los mamíferos de Argentina. http://cma.sarem.org.ar/es/especie-nativa/pteronura-brasiliensis

IUCN/SSC (2013). Guidelines for Reintroductions and Other Conservation Translocations. Version 1.0. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN Species Survival Commission, 57 pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1609-1 https://portals.iucn.org/library/efiles/documents/2013-009.pdf

Leuchtenberger, C., Di Martino, S., Cerón, G., Serrano-Spontón, A., and Donadio, E. (2021). Hope for an apex predator: giant otters rediscovered in Argentina. Oryx, 55, 810-811. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605321001071

Zamboni, T., Peña, J., Di Martino, S., and Leuchtenberger, C. (2018). Experimental reintroduction of the giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) in the Iberá Park (Corrientes, Argentina). CLT The Conservation Land Trust. https://docplayer.net/160028688-Experimental-reintroduction-of-the-giant-otter-pteronura-brasiliensis-in-the-ibera-park-corrientes-argentina.html

Résumé: Nouveaux Enregistrements Confirmés de Loutre Géante (Pteronura brasiliensis, Gmelin, 1788) en Argentine

Nous rapportons ici deux observations indépendantes et confirmées de loutre géante solitaire (Pteronura brasiliensis) enregistrées en décembre 2021 et septembre 2022 en Argentine. La première observation, un mâle vu pour la première fois dans le parc national d'El Impenetrable en mai 2021, a été enregistrée dans la province de Buenos Aires, qui se situe en dehors de la répartition historique connue des loutres géantes. La deuxième observation, un adulte de sexe inconnu, a été enregistrée dans le parc Iberá, province de Corrientes, où la loutre géante a disparu il y a plus de 30 ans. Ces enregistrements soulignent l'urgence de stratégies de gestion visant à améliorer le rétablissement des populations de loutres géantes dans leur aire de répartition historique.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Nuevos Registros Confirmados de Nutria Gigante (Pteronura brasiliensis, GMELIN, 1788) en Argentina

Aquí, informamos dos observaciones independientes y confirmadas de nutrias gigantes (Pteronura brasiliensis) solitarias, registradas en Diciembre de 2021 y Septiembre de 2022 en Argentina. La primer observación, un macho que había sido visto en el Parque Nacional El Impenetrable en Mayo de 2021, fue registrada en la provincia de Buenos Aires, que está fuera de la distribución histórica conocida de la nutria gigante. La segunda observación, un adulto de sexo desconocido, fue registrada en el Parque Iberá, provincia de Corrientes, donde la nutria gigante desapareció hace más de 30 años. Éstos registros destacan la urgencia de tener estrategias de manejo dirigidas a reforzar la recuperación de las poblaciones de nutria gigante en su área de distribución histórica.

Vuelva a la tapa