IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Citation: Correa, R. and Pizarro, J. (2023). Mortality of Lontra felina (Molina, 1782) in Chile (2009-2022) based on Reports. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 40 (3): 144 - 150

Mortality of Lontra felina (Molina, 1782) in Chile (2009-2022) based on Reports

Ricardo Correa1, and José Pizarro2*

1LAFKEN NGO, Chile

2OSG IUCN, Perú

Received 7th March 2023, accepted 1st May 2023

Abstract: This note reports 58 dead marine otters along the coast of North and central Chile during 2009-2022. The data was retrieved from a database of the Chilean National Service for Fisheries and Aquaculture (SERNAPESCA) and from observations of the authors. The main part of the otter mortality reports occurred in the Valparaíso region, which in turn would be consequence of a major effort to report mortality events by volunteers and scientists here. Seventeen (29%) cases of otter mortality were identified whereby interaction with thermal power plants cooled by seawater, attack of dogs, and interaction with small-scale fisheries are the main causes of mortality. But the cause of almost all the deaths remains unknown.

Keywords: Mortality, by-catch, habitat, invasive species

INTRODUCTION

The marine otter Lontra felina (Molina, 1782) is distributed mainly along the rocky shore of Peru and Chile and being classified as an Endangered species at global level (Mangel et al., 2022). Currently the species well-known as “chungungo” is legally protected in Chile as a hydrobiological resource according with the Decree N°430 from 31 January 2023 (Ministerio de Economía Fomento y Reconstrucción, 2023). Also, L. felina was recently classified in Chile as Endangered A4ce category (Ministerio del Medio Ambiente, 2023).

Habitat fragmentation, attack by dogs, entanglement in small-scale fishing gear as well as pollution are the main threats to the marine otter in Chile (Sielfeld and Castilla, 1999; Medina-Vogel et al., 2007; Duplaix and Savage, 2018). However, few instances of deaths as a consequence of these causes are documented (Rozzi and Torres-Mura, 1990; Pizarro, 2008; Mangel et al., 2011; Cursach et al., 2012; Pizarro et al., 2022).

Mortality events of L. felina in Chile during 2009-2022 are presented in this work using mainly the database of the National Service of Fishing and Aquaculture of Chile (SERNAPESCA by its acronym in Spanish).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

The study covers the regions of Arica y Parinacota, Tarapacá, Antofagasta, Atacama, Coquimbo, Valparaíso, Bio-Bio, and Los Ríos y Los Lagos. All localities from the analyzed database correspond to the Humboldtian, Chile Central and Araucarian ecoregions of the Warm-temperate Southeastern Pacific Province (Spalding et al., 2007).

Methods

The database of stranded marine fauna from the National Service of Fishing and Aquaculture of Chile for the period 2009-2022 (SERNAPESCA, 2023) was used to obtain data on live and dead marine otters. The database was filtered using the metadata species = Lontra felina and searching information about sex of the specimen, date and locality of the event and cause of the death. In this way, a new database of reports on dead marine otters in Chile (2009-2022) was built, which can be downloaded from https://figshare.com/s/f61e67db869a7e508b51. In addition, the authors searched for some cases not registered in the SERNAPESCA database, and then those reports were incorporated into the new database. The reports not registered by SERNAPESCA were supported by two reports of necropsies and photographs. Finally, mortality cases of anthropogenic origin were identified using the data shown in the SERNAPESCA database as well the results of necropsies and observations of the authors. The database of SERNAPESCA contains reports verified by the officials of this agency and therefore included in the data sheet as observations of each mortality event. Observations by the authors were verified with photographs as well as the two necropsy reports (Table 1).

| Table 1: Mortality events of Lontra felina by anthropic source. Chile (2013-2022). | ||||

| N° | Dead Animals | Locality/Coordinates | Date |

Cause/Source |

| 1. | One individual. No sex identified0 | Yachting beach, Algarrobo, Valparaíso Region. 33°21´43.9¨S 71°40´19.5¨W | 24 January 2013 | Crushed by boat (SERNAPESCA, 2023). |

| 2. | One male individual. | San Vicente small-scale fishing town, Talcahuano, Bio-Bio Region. 36°43´33.8¨S 73°07´59.25¨W | 31 May 2013 | Otter crushed, presumably by boat (SERNAPESCA, 2023). |

| 3. | One individual. No sex identified | Quintero Bay, Valparaíso Region. 32°45´58.4¨S 71°29´31¨W | 24 September 2014 | Died impregnated by oil after oil spill (Supreme Court of Justice of Chile, 2019). |

| 4. | One cub without sex identification | Puchuncaví, Valparaíso Region. 32°44´43.3¨S 71°29´18¨W | 31 December 2016 | Attack of dogs (Ricardo Correa, Fig. 2) |

| 5. | One male individual. | Coquimbo, Coquimbo Region. 29°57´8.15¨S 71°20´7.94¨W | 3 October 2017 | Road-kill (SERNAPESCA, 2023) |

| 6. | One individual. No sex identified. | Maitencillo beach, Valparaíso Region. 32°39´19.15¨S 71°26´35.4¨W | 12 June 2018 | Attacked by dog (SERNAPESCA, 2023). |

| 7. | One male individual. | AES-Gener thermal power station, Las Ventanas, Valparaíso Region. 32°44´57.5¨S 71°29´17.7¨W | 5 September 2018 | Died by asphyxia within power station (Necropsy report translation by Ricardo Correa, 2023a) |

| 8. | One pup without sex identification. | Quintero Bay Valparaíso Region. 32°44´38.8¨S 71°29´28¨W | 5 March 2019 | Entangled in fishing gear (Ricardo Correa, Fig. 3) |

| 9. | One individual. No sex identified. | La Rinconada, Antofagasta Región. 23°28´0.48¨S 70°27´45.68¨W | 12 June 2019 | Crushed by boat (SERNAPESCA, 2023). |

| 10. | One male individual. | Small-scale fishing village of Tongoy. Coquimbo Region. 30°15´22.9¨ S 71°29´´58.13¨W | 27 February 2020 | Died in crustacean trap (SERNAPESCA, 2023). |

| 11. | One female individual. | Las Conchitas beach, Puchuncaví, Valparaíso Region. 32°44´9¨S 71°30´00¨W | 11 June 2020 | Attack of dog (Necropsy report translation by Ricardo Correa, 2023b). |

| 12. | One individual. No sex identified. | Playa Grande, Valdivia, Los Ríos Region. 39°51´41.15¨S 73°23´38.21¨W | 30 October 2020 | Died in crustacean trap (SERNAPESCA, 2023). |

| 13. | One individual. No sex identified. | AES-Gener thermal power station, Tocopilla, Antofagasta Region. 22°05´41¨S 70°12´38¨W | 24 November 2020 | Trapped at power station (SERNAPESCA, 2023). |

| 14. | One individual. No sex identified. | El Apolillado, La Higuera, Coquimbo Region. 29°12´29.6¨S 71°29´38.08¨W | 28 May 2021 | Entangled in artisanal fishing gear (SERNAPESCA, 2023). |

| 15. | One individual. No sex identified. | AES-Gener thermal power station, Tocopilla, Antofagasta Region. 22°05´43¨S 70°12´38¨W | 12 September 2021 | Wounded by propeller at power station (SERNAPESCA, 2023). |

| 16. | One male individual. | Antofagasta, Antofagasta Region. 23°30´24¨S 70°25´26¨W | 20 June 2022 | Attacked by dog (SERNAPESCA, 2023). |

| 17. | One individual. No sex identified. | AES-Gener thermal power station, Puchuncaví, Valparaíso Region. 32°44´S 71°29´W | 24 July 2022 | Died at power station (SERNAPESCA, 2023). |

RESULTS

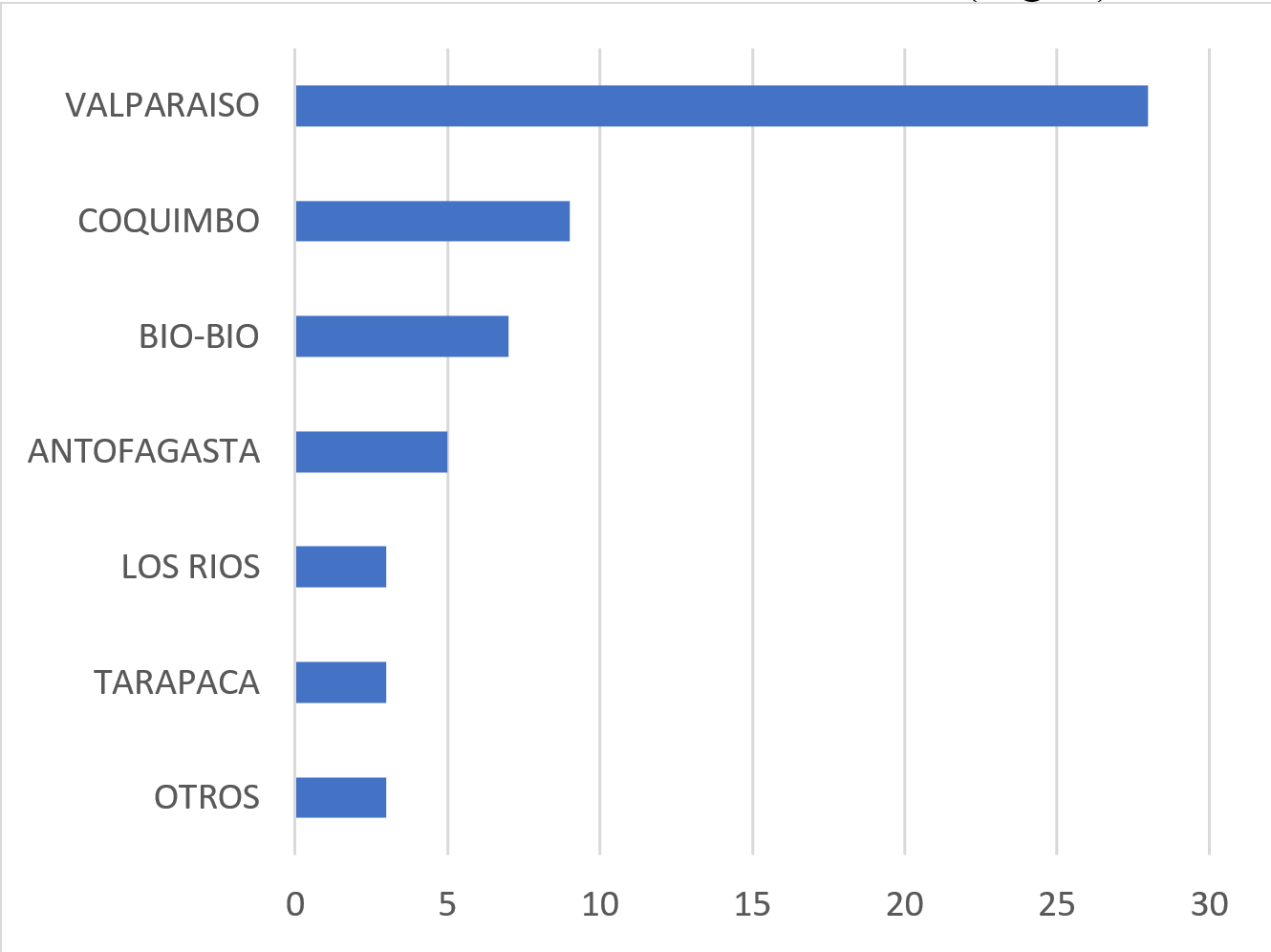

We found 58 reported cases of dead marine otters in Chile during 2009-2022. 48 (83%) cases were finding out in the database of SERNAPESCA, as well as nine (16%) additional cases based in archives of the authors and one documented in a court ruling (Supreme Court of Justice of Chile, 2019). Valparaíso was the region of Chile with most reports of dead marine otters between 2009 and 2022 (Fig. 1).

There is evidence of anthropogenic causes of the death of marine otters in at least seventeen cases. However, there is no information available on the cause of death from the other 41 reported cases (Table 1).

Another result of interest is that the months with more deaths reported are January, February, and June. Likewise, the reports of dead marine otters have increased in the last years, from one report in 2009 to 16 cases in 2022.

DISCUSSION

Most dead otters were found in the Valparaíso region. Valparaíso and other regions such as Coquimbo and Atacama are within the ecoregion Chile Central, which is characterized by being a transitional zone between the very productive Humboldtian and the coldest Araucanian ecoregion, but is impacted by coastal pollution from industries and ports as well (Sullivan Sealey and Bustamante, 1999). Currently, the Valparaíso region is the second largest urban agglomeration in Chile and its coastal population has increased at an average rate of 25% during the last three decades, an extreme urbanization process, and has several tourism facilities, industrial plants and the three most important ports in the country: Valparaíso, San Antonio and Port Quintero-Ventanas (Rangel-Buitrago et al., 2018).

Although only four cases of dead otters were found at power stations, the Chilean Institute for Fisheries Development (IFOP by its acronym in Spanish) indicates that it is a threat for marine otters in Chile (IFOP, 2016). Thermal power stations are considered a threat to marine otters because these animals could die when attempt to enter the plants, suffering asphyxia in the suction ducts or wounds produced by propellers that suck seawater. Cases of interaction of otters with these plants have been reported in Tocopilla, Antofagasta Region and in Puchuncaví, Valparaíso.

In the SERNAPESCA database, it also appears that some marine otters died entangled in fishing gear, such as fishing nets and crustacean traps (Table 1). This situation is recurrent in Peru, where individuals died by asphyxia when they are entangled in artisanal fishing nets (Pizarro, 2008). Marine otters crushed by boats could be a consequence of the opportunistic foraging of the species over fish discards obtained at the small fishing villages wherein they currently arrive to feed and live (Cursach et al., 2012; Badilla and George-Nascimento, 2009).

Another mortality cause reported is the attack of dogs on marine otters (Table 1), which confirms how serious this threat for the otters is in Chile, as has also been mentioned by other authors (Cursach et al., 2012; Sepúlveda et al., 2014). The deaths caused by dogs recorded in this study occurred on open beaches, disturbed by human presence and where marine otters are exposed to attack by dogs (Medina-Vogel et al., 2008). The only reported death of an otter due to road-kill did not occur on a highway as happens in Europe with the Eurasian otter (Kruuk and Conroy, 1991), but within a port because marine otters live mainly on coastal and their refuges are associated with the availability of food and the protection of their dens against the waves, which can be near fishing towns or ports (Medina-Vogel et al., 2007).

CONCLUSIONS

The cause of death for marine otters is unknown in most cases. Deaths of anthropogenic origin were identified for only seventeen marine otters. It is probable that a greater number of interactions with otters and a greater effort to report otter mortality events may be the reasons why Valparaíso is the region of Chile with most reports of dead marine otters in Chile during the last 13 years. Furthermore, interaction with power stations cooled by seawater, attack by dogs and incidental death during small-scale fishing activities are the main human-made mortality causes identified in the present work.

REFERENCES

Badilla, M., George-Nascimento, M. (2009). Conducta diurna del Chungungo Lontra felina (Molina, 1782) en dos localidades de la costa de Talcahuano, Chile: ¿efectos de la exposición al oleaje y de las actividades humanas?. Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía 44: 409-415. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-19572009000200014 [In Spanish, with abstract in English].

Correa, R. (2023) a. Transcript and translation of the preliminary necropsy report of chungungo (Lontra felina) Valparaíso region (09/13/2018) by Ricardo Gonzalo Correa. [figshare. Dataset]. https://figshare.com/s/1aa673d887b83b24cfee

Correa, R. (2023) b. Transcript and translation of the preliminary necropsy report of chungungo (Lontra felina) Valparaíso region (06/16/2020) by Ricardo Gonzalo Correa. [figshare. Dataset]. https://figshare.com/s/05274948d5141cd0c64b

Corte Suprema de Justicia de Chile-Tribunal ambiental (2019). Sentencia de Reemplazo. Sentencia Rol N° 41.790 – 2016 de la Corte Suprema, de 7 de agosto de 2017. https://www.tribunalambiental.cl/wpcontent/uploads/2020/03/CS_13177-2018_2TA_D-13-2014_Sentenciareemplazo.pdf

Cursach, J.A., Rau, J.R., Ther, F., Vilugrón, J., Tobar, C.N. (2012). Sinantropía y conservación marina: el caso del chungungo Lontra felina en el sur de Chile. Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía, 47(3), 593-597. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-19572012000300022 (In Spanish, with abstract in English).

Duplaix, N., Savage, M. (2018). The Global Otter Conservation Strategy. Salem, Oregon, USA: IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group. https://www.otterspecialistgroup.org/osg-newsite/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/IUCN-Otter-Report-DEC%2012%20final_small.pdf

IFOP (2016). Informe Final “Determinación de los impactos en los recursos hidrobiológicos y en los ecosistemas marinos presentes en el área de influencia del derrame de hidrocarburo de Bahía Quintero, V Región”. Subsecretaria de Pesca y Acuicultura. Santiago; División de Investigación Pesquera, Instituto de Fomento Pesquero. 711 p. https://www.subpesca.cl/portal/618/articles-97154_documento.

Jefferson, T.A., Webber, M.A., Pitman, R.L. (2015). Marine Mammals of the World. Comprehensive guide to their identification, Second edition. Jefferson. London, San Diego, Waltham, Oxford: Academic Press-Elsevier.

Kruuk, H., Conroy, J.W.H. (1991). Mortality of otters (Lutra lutra) in Shetland. Journal of Applied Ecology 28: 83-94. https://doi.org/10.2307/2404115

Mangel, J., Alfaro-Shigueto, J., Verdi, R., Rheingantz, M.L. (2022). Lontra felina. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2022: e.T12303A215395045. Accessed on 11 February 2023.

Mangel, J.C., Whitty, T., Medina‐Vogel, G., Alfaro‐Shigueto, J., Cáceres, C., Godley, B.J. (2011). Latitudinal variation in diet and patterns of human interaction in the marine otter. Marine Mammal Science, 27(2): E14-E25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00414.x

Medina-Vogel, G., Boher, F., Flores, G., Santibañez, A., Soto-Azat, C. (2007). Spacing behavior of marine otters (Lontra felina) in relation to land refuges and fishery waste in central Chile. Journal of Mammalogy, 88: 487-494. https://doi.org/10.1644/06-MAMM-A081R1.1

Medina‐Vogel, G., Merino, L.O., Monsalve Alarcón, R., Vianna, J.D.A. (2008). Coastal-marine discontinuities, critical patch size and isolation: implications for marine otter conservation. Animal Conservation, 11: 57-64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-1795.2007.00151.x

Ministerio de Economía, Fomento y Reconstrucción (2023). Decreto 430 fija el texto refundido, coordinado y sistematizado de la ley n° 18.892, de 1989 y sus modificaciones, ley general de pesca y acuicultura. https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=13315

Ministerio del Medio Ambiente (2023). Inventario Nacional de Especies de Chile. Lontra felina. http://especies.mma.gob.cl/CNMWeb/Web/WebCiudadana/ficha_indepen.aspx?EspecieId=9&Version=1

Pizarro, J. (2008). Mortality of the marine otter (Lontra felina) in southern Peru. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin 25: 94-99. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume25/Pizarro_2008.html

Pizarro, J., Cabezas, G.C., Cruz, L.A.J. (2022). Nuevas observaciones de Lontra felina (Molina, 1782) en el litoral de Lima y Callao, Perú. Biotempo, 19: 259-264. https://doi.org/10.31381/biotempo.v19i2.5029 (In Spanish, with abstract in English).

Ralls, K., Sinif, D.B. (1990). Sea Otters and Oil: Ecological Perspectives. In: Geraci, J.R., St. Austin, D.J. (eds.). Sea Mammals and Oil: Confronting the Risks, p. 199-210. San Diego: Academic Press.

Rangel-Buitrago, R., Contreras-López, M., Martínez, C., Williams, A. (2018). Can coastal scenery be managed? The Valparaíso region, Chile as a case study. Ocean and Coastal Management, 136: 383-400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.07.016

Rozzi, R., Torres-Mura, J.C. (1990). Observaciones de nutria marina o chungungo (Lutra felina) al sur de la Isla Grande de Chiloé: Antecedentes para su Conservación. Revista Medio Ambiente, 11(1): 24-28. [In Spanish, with abstract in English].

Sepúlveda M.A, Singer R.S., Silva-Rodriguez E., Stowhas P., Pelican, K. (2014). Domestic dogs in rural communities around protected areas: conservation problem or conflict solution?. PLoSONE 9: e86152. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086152

SERNAPESCA (2023). Registro de varamientos desde el año 2009 a diciembre de 2022. Servicio Nacional de Pesca y Acuicultura. http://www.sernapesca.cl/informacion-utilidad/registro-de-varamientos

Sielfeld, W., Castilla, J.C. (1999). Estado de conservación y conocimiento de las nutrias en Chile. Estudios Oceanológicos, 18: 69-79. https://repositorio.uc.cl/handle/11534/17272 [In Spanish, with abstract in English].

Spalding, M.D., Fox, H.E., Allen, G.R., Davidson, N., Ferdaña, Z.A., Finlayson, M.A.X., Halpern B.S., Jorge, M.A., Lombana, A.L., Lourie, S.A., Martin, K.D., McManus E., Molnar, J., Recchia, C.A., Robertson, J. (2007). Marine ecoregions of the world: a bioregionalization of coastal and shelf areas. BioScience, 57: 573-583. https://doi.org/10.1641/B570707

Sullivan Sealey, K., Bustamante, G. (1999). Setting geographic priorities for marine conservation in Latin America and the Caribbean. Arlington, VA: The Nature Conservancy.https://bvearmb.do/bitstream/handle/123456789/3108/Pnach523.pdf?sequence=1

Valqui, J. (2012). The marine otter Lontra felina (Molina, 1782): A review of its present status and implications for future conservation. Mammalian Biology, 77: 75-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mambio.2011.08.004

Résumé: Mortalité de Lontra felina (Molina, 1782) au Chili (2009-2022) sur Base des Rapports

Cette note fait état de 58 loutres marines mortes le long de la côte du nord et du centre du Chili entre 2009 et 2022. Les données ont été extraites d'une base de données du Service National Chilien de la Pêche et de l’Aquaculture (SERNAPESCA) et les observations des auteurs. La majeure partie des rapports de mortalité de loutres a eu lieu dans la région de Valparaíso, ce qui serait une conséquence d’un effort majeur destiné à signaler les faits de mortalité par des volontaires et des scientifiques locaux. Les principales causes de mortalité, soit dix-sept loutres identifiées (29%), sont liées aux centrales thermiques refroidies par eau de mer, à l’attaque de chiens et à la pêche artisanale. Cependant, la cause de la majorité des décès reste inconnue.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Mortalidad de Lontra felina (Molina, 1782) en Chile (2009-2022) en Base a Reportes.

Ésta nota reporta 58 nutrias marinas muertas a lo largo de la costa de Chile Norte y Central, durante 2009-2022. Los datos fueron extraídos de una base de datos del Servicio Nacional de Pesca y Acuicultura de Chile (SERNAPESCA) y de observaciones de los autores. La parte principal de los reportes la mortalidad de nutrias ocurrió en la región de Valparaíso, lo que a su vez sería consecuencia de un importante esfuerzo para reportar los eventos de mortalidad por parte de voluntarios y científicos allí. Fueron identificados diecisiete casos (29%) de mortalidad de nutrias en los que las principales causas de la mortalidad fueron interacción con plantas térmicas de energía con enfriamiento mediante agua de mar, ataque por perros, e interacción con pesquerías de pequeña escala. Pero la causa de casi todas las muertes permanece desconocida.

Vuelva a la tapa