IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Citation: Claverie, A. Ñ., and Valenzuela, A.E.J..(2023). New Records for the Marine Population of Southern River Otter Lontra provocax: Confirming Huillín Presence on Mitre Peninsula, Tierra Del Fuego, Argentina. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 40 (3): 137 - 143

New Records for the Marine Population of Southern River Otter Lontra provocax: Confirming Huillín Presence on Mitre Peninsula, Tierra Del Fuego, Argentina

Alfredo Ñ. Claverie1*, and Alejandro E.J. Valenzuela1,2

1Wildlife Conservation, Research and Management Group (CIMaF). Institute of Polar Science, Environment and Natural Resources (ICPA), National University of Tierra Del Fuego (UNTDF) and National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET)

2Lontra provocax Species Coordinator, Otter Specialist Group, Species Survival Commission, International Union for Conservation of Nature

*Correspondance Email: aclaverie@untdf.edu.ar

Received 21st March 2023, accepted 25th April 2023

Abstract: The southern river otter (Lontra provocax), known as huillín in Spanish, is an endangered otter that is endemic to Patagonia. Argentina has two populations separated by 1,500 km: a freshwater one in northern Patagonia, and a coastal marine one in Tierra del Fuego province. This last population was categorized as critically endangered, and until now only presents two stable subpopulations inside protected areas (Tierra del Fuego National Park and Staten Island Provincial Reserve). Several sporadic records of this species were known for Mitre Peninsula (Tierra del Fuego), a difficult area to access. The goal of this study was to evaluate the status of the southern river otter on Mitre Peninsula. In 2018, 2021, 2022 and 2023, we systematically surveyed the southern coasts of this area (the only with suitable habitat), looking for otter presence through signs (e.g., spraints, tracks, dens). Additionally, camera traps were set in areas with high activity. We found new records and also confirm a stable presence of the species in the area. Camera trap records also confirm presence throughout the year and the first known confirmation of reproduction. Additionally, introduced species, like American mink (Neogale vison) and free-range dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) were identified, which are potential threats to the otter. We believe that this evidence of huillín presence on Mitre Peninsula implies there is a stable subpopulation, which would also mean that Mitre Peninsula represents a potential biological corridor between Staten Island and the rest of the archipelago.

Keywords: Endangered; Endemic; Mitre Peninsula; Patagonia

INTRODUCTION

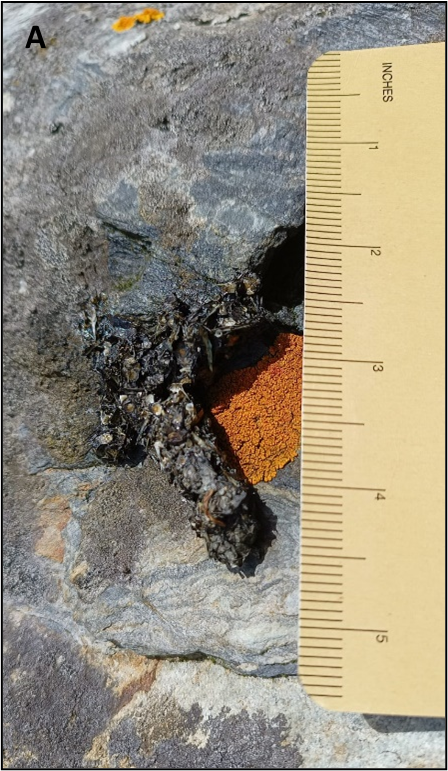

The southern river otter (Lontra provocax), also called huillín in Spanish, is a semiaquatic carnivore that is endemic to Argentine and Chilean Patagonia (Chehébar, 1985; Kruuk, 2006). It is one of the otter species with most restricted range in the world (Chehébar et al., 1986) and inhabits both freshwater river and lake shores in northern Patagonia and marine coasts along the channels and fjords of southern Patagonia (Sepúlveda et al., 2015; 2019). In general, this species uses natural cavities between rocks, tree trunks or shrubs in areas with high vegetation cover to establish it dens, resting places, latrines, etc. (Valenzuela et al., 2013).

During the last century, this species was hunted for its fur leading to a severe decline of its populations and driving this otter to its present endangered status (Sielfeld and Castilla, 1999; Cassini et al., 2010). Moreover, despite a ban on hunting, to date the species has not recovered, mainly because it continues to be threatened by degradation, fragmentation and loss of riparian and coastal habitats, unplanned urbanizations, unregulated human activities, and interaction with invasive introduced carnivores, such as feral dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) and American mink (Neogale vison) (Valenzuela et al., 2012; Valenzuela, 2019; Sepúlveda et al., 2019; Barbe et al., 2023; Claverie et al., 2023). For these reasons, currently the southern river otter is categorized as Endangered internationally (Sepúlveda et al., 2015) and in Argentina (Valenzuela et al., 2019). In particular, in 2019 the Argentine Society for the Study of Mammals (SAREM in Spanish) together with the Argentine Ministry of Environment, and following the IUCN rules to categorize species conservation status at a regional level, classified the Argentine coastal marine population of southern river otters as Critically Endangered, estimating that only 50 individuals remain in the Argentine portion of Tierra del Fuego (Valenzuela et al., 2019).

The southern river otter’s distribution in Argentina represents the extremes of the species’ global distribution, with two populations separated for more than 1,500 km: a freshwater population in Nahuel Huapi National Park in northern Patagonia, and a coastal marine population in the Argentine portion of the Tierra del Fuego Archipelago (Chehébar, 1985; Centrón et al., 2008; Valenzuela et al., 2013). This latter population has two relatively stable sub-populations in Tierra del Fuego National Park (TFNP; Schiavini and Bugnest, 1994; Malmierca et al., 2006; Rocha and Valenzuela, 2015) and Staten Island Provincial Reserve (Valenzuela et al., 2017). Historical data suggest that the species was present all along the Beagle Channel and on Mitre Peninsula (MP) (Valenzuela et al., 2019). During a preliminary field trip to the MP’s Aguirre Bay, performed in 2016, an otter spraint was found (Valenzuela et al., 2021), evidencing the need for further research. However, no systematic survey for otter presence has been performed on MP until now, mainly due to it being an isolated and logistically complicated area to visit and work in. Yet, MP was recognized as a priority area for otter research and conservation by both the Binational (Argentina-Chile) Meeting for Conservation of Southern River Otter (Valenzuela, 2019) and the Global Otter Strategy (Sepulveda et al., 2019). Additionally, this area represents a potential biological corridor that connects the otters of Staten Island (southeast extreme of the world-wide range of this species) with the rest of its distribution.

In this publication, we present the results of the first systematic prospection for southern river otter on Mitre Peninsula, performed during 2018, 2021, 2022 and 2023, providing new otter records for the area.

STUDY AREA

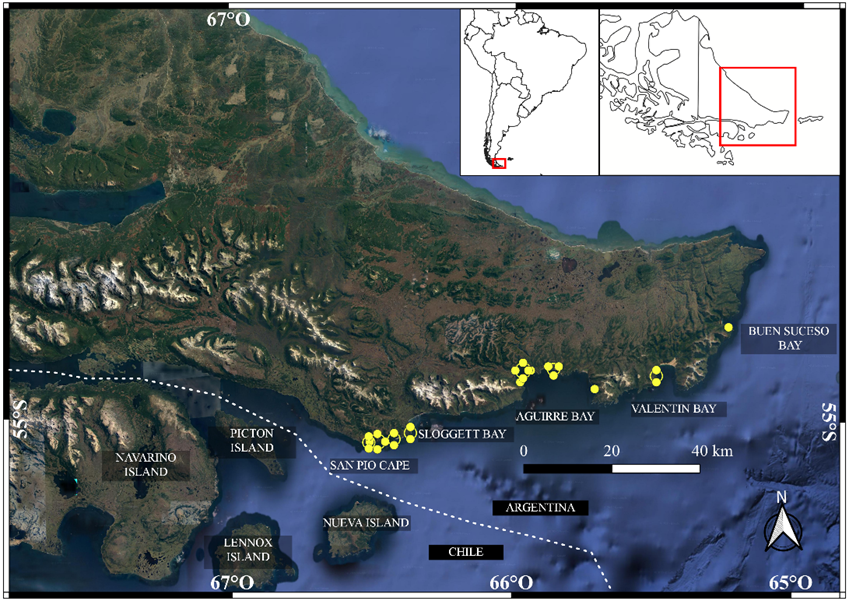

Mitre Peninsula constitutes the eastern extreme of the Tierra del Fuego Island (between 54°30’–55°03’S and 65°06’–66°44’ O; Fig. 1). The climate of this region is characterized by two main seasons: a long cold winter and a short cool summer (Tuhkanen et al., 1989). The vegetation along the peninsula’s southern coast is dominated by Nothofagus trees (Pisano, 1977). Its southern coast also is characterized by the presence of cliffs, formed by the Andes Mountain Range, which plunge into the sea, unlike the northern coast, which is made up mainly of low-slope bays (Isla, 1994).

METHODOLOGY

Based on the southern river otter habitat suitability model for Tierra del Fuego presented by Valenzuela et al. (2013) and using satellite images (Google Earth Pro 7.3.4), a total of 130 km of coastline were considered apt for otters, taking into account inherent environmental characteristics like vegetation, slope, orientation, etc. Based on presence of suitable habitat and logistical feasibility, a total of 71 km of the coastline were surveyed by foot between the summer seasons of 2018, 2021, 2022 and 2023, including all main bays in the area (Sloggett, Aguirre, Valentín and Buen Suceso), San Pio Cape and associated exposed coasts (Fig. 1). This sampling effort represents 54% of the coastline described as suitable, and it is comparable, or even exceeds, the efforts carried out for otter research in both Patagonia and Europe (Chehebar, 1985; Bonesi and Macdonald, 2004; Fasola et al., 2009). In each sector, otter signs, such as spraints, tracks, latrines or dens, were recorded. Additionally, in three sites with high otter activity (large amount of scats and/or recognizable dens), digital sensor motion camera traps with non-invasive black flash (Bushnell Trophy Cam HD) were set (Fig. 2). Cameras were active continuously, taking one photo and one video for 15 seconds upon being triggered (and a period of at least one hour between triggering events).

RESULTS

Numerous signs of southern river otter were found in all sites surveyed (Sloggett, Aguirre, Valentín, Buen Suceso Bays and San Pio Cape), which confirms the presence of the species along the PM’s southern coasts (Fig. 1). A total of 124 spraints were found, distributed as follows by site: 60 in San Pio Cape, 37 in Aguirre Bay, 22 in Sloggett Bay, four in Valentín Bay and one in Buen Suceso Bay. Depending on the level of activity, the camera traps were placed, two in Aguirre Bay, and one in Sloggett Bay (Fig. 2). Cameras registered 503 records of the species, detecting its presence all year long, and also documenting reproduction activity in both sites, with eight different records of juveniles in the dens. Also, an individual was sighted near San Pio Cape during the last survey in 2023 (Fig. 2). In addition to spraints, the cameras and other sign evidence, we documented invasive introduced American mink (Neogale vison) and free-range dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) in the entire study area.

DISCUSSION

These results represent the first systematic survey of southern river otters on MP. To our knowledge this study involved the first use of camera traps in the area, as well. A relatively stable otter presence was observed throughout the year and between years, and there was documentation of reproductive events. These results imply that there is an established subpopulation of otters on MP that should be taken into account in future research, management and conservation decisions regarding this species. However, despite being isolated, this population does not escape the general threats to otter conservation, such as invasive introduced mink and dogs and unregulated human activities (Valenzuela et al., 2019). On the other hand, our results also support the hypothesis that MP is a potential biological corridor between the Staten Island subpopulation and the rest of the distribution. Additionally, the higher activity in San Pio Cape and Sloggett Bay highlights the importance of this sector. This area is located adjacent to several channels between the Chilean islands of Navarino, Picton, Nueva and Lennox, suggesting a possible connection with these areas from the south of Navarino Island, and both subpopulations of the Argentine Beagle Channel in the south of Tierra del Fuego Island, TFNP and MP. Furthermore, individuals from San Pio Cape and MP eventually connect the rest of these subpopulations with the most extreme eastern portion of this species range on Staten Island. In general, these results highlight the important value of MP for the southern river otter, which was recently declared a provincial natural monument (Provincial Law #1346) and also reinforces the need to include this species in decision-making and the future management plan of the recently passed law that declares MP as Provincial Natural Protected Area. Further research is needed to understand the situation of the species in MP, including long-term monitoring, studies of habitat use, estimations of relative abundance, quantification of diet and genetic analysis, etc. This information will be important to develop effective conservation strategies taking into account the critical situation of the southern river otter in Argentina generally and Tierra del Fuego specifically.

REFERENCES

Barbe, I., Claverie, A.Ñ., Valenzuela, A.E.J. (2023). Canis lupus familiaris Domestic feral dog, perro doméstico asilvestrado. In: Valenzuela, A.E.J., Anderson, C.B., Ballari, S.A., Ojeda, R.(Eds). Introduced Invasive Mammals of Argentina. Serie A, Mammalogical Research (Investigaciones Mastozoológicas). Volumen 3. 1ª edición. Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos SAREM, Buenos Aires, Argentina. pp. 243-248.

Bonesi, L., Macdonald, D.W. (2004). Differential habitat use promotes sustainable coexistence between the specialist otter and the generalist mink. Oikos. 106: 509-519. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2004.13034.x

Cassini, M.H., Fasola, L., Chehébar, C., Macdonald, D.W. (2010). Defining conservation status using limited information: the case of Patagonian otters Lontra provocax in Argentina. Hydrobiologia, 652: 389-394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-010-0332-6

Centron, D., Ramirez, B., Fasola, L., Chehebar, C., Schiavini, A., Cassini, M. (2008). Diversity of mtDNA in Southern River Otter (Lontra provocax) from Argentinean Patagonia. Journal of Heredity 99: 198-201. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esm117

Chehébar, C. (1985). A survey of the Southern river otter Lutra provocax Thomas in Nahuel Huapi National Park, Argentina. Biological Conservation 32: 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(85)90020-5

Chehébar, C.E., Gallur, A., Giannico, G., Gottelli, M.D., Yorio, P. (1986). A survey of the Southern river otter Lutra provocax in Lanin, Puelo and Los Alerces National Parks, Argentina, and evaluation of its conservation status. Biological Conservation 38: 293-304. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(86)90056-X

Claverie, A.Ñ., Barbe, I., Villagra, L.A., Valenzuela, A.E.J. (2023). Neogale vison : American mink, visón americano. In: Valenzuela, A.E.J., Anderson, C.B., Ballari, S.A., Ojeda, R. (Eds). Introduced Invasive Mammals of Argentina. Serie A, Mammalogical Research (Investigaciones Mastozoológicas). Volumen 3. 1ª edición. Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos SAREM, Buenos Aires, Argentina. pp. 323-328.

Fasola, L., Chehébar, C., Macdonald, D.W., Porro, G., Cassini, M.H. (2009). Do alien North American mink compete for resources with native South American river otter in Argentinean Patagonia? Journal of Zoology. 277: 187-195. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.2008.00507.x

Isla, F.I. (1994). Evolución comparada de bahías de la península Mitre, Tierra del Fuego. Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina. 49: 197-205. [in Spanish with English abstract]

Kruuk, H. (2006). Wild otters, predation and populations. Oxford University press, United Kingdom. ISBN 978-0198540700

Malmierca, L., Gallo, E., Calvi, M., Ferrari, N.L. (2006). Monitoreo y uso de cuevas del huillín en el Parque Nacional Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. In: Cassini, M. and Sepúlveda, M. (Eds.). El huillín | Lontra provocax. Investigaciones sobre una nutria patagónica amenazada de extinción. Buenos Aires. Organización Profauna pp 127-132.

Pisano, E. (1977). Fitogeografía de Fuego-Patagonia Chilena. I. Comunidades vegetales entre las latitudes 52° y 56°S. Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia. 8: 121-250. [in Spanish with English abstract].

Rocha, D., Valenzuela, A.E.J. (2015). Patrones de actividad en madrigueras de huillín en la costa del Parque Nacional Tierra del Fuego. Technical report. Argentine National Parks Administration. Ushuaia. [in Spanish]

Schiavini, A., Bugnest, F. (1994). Status y conservación de las nutrias (Lutra sp.) en el Parque Nacional Tierra del Fuego. Technical report. Argentine National Parks Administration. Ushuaia. [in Spanish]

Sepúlveda, M., Pozzi, C., Chehébar, C., Fasola, L., Valenzuela, A.E.J. (2019). Southern river otter (Lontra provocax). In: Duplaix, N y Savage M (Eds) The Global Otter Conservation Strategy. IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group. Oregon, USA. pp. 96-100.

Sepúlveda, M.A., Valenzuela, A.E.J, Pozzi, C., Medina-Vogel, G., Chehébar, C. (2015). Lontra provocax. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T12305A95970485.en

Sielfeld, W., Castilla, J. C. (1999). Estado de conservación y conocimiento de las nutrias en Chile. Scientific. Estud. Oceanol. 18: 69-79. [in Spanish with English abstract]

Tuhkanen, S., Kuokka, I., Hyvonen, J., Stenroos, S., Niemela, J. (1989). Tierra del Fuego as a target for biogeographical research in the past and present. Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia. 19(2): 5-107.

Valenzuela A.E.J., Fasola, L., Pozzi, C., Chehébar, C., Ferreyra, N., Gallo, E., Massaccessi, G. (2019). Lontra provocax. Recategorización de Mamíferos Argentinos. Lista Roja de Mamíferos de Argentina. SAREM y SAyDS. https://cma.sarem.org.ar/es/especie-nativa/lontra-provocax

Valenzuela, A.E.J, Gallo, E., Pozzi, C., Fasola, L., Chehébar, C. (2012). Lontra Provocax., In: Ojeda, R.A., Chillo, V., Díaz Isenrath, G.B. (Eds.). Libro Rojo de Mamíferos Amenazados de la Argentina. Ediciones SAREM, Buenos Aires, Argentina, pp. 105-107. [in Spanish with English abstract]

Valenzuela, A.E.J. (2019). Informe Reunión Binacional (Argentina-Chile) para la conservación del huillín (Lontra provocax), Ushuaia, Julio 2018. Informe Técnico para la Secretaría de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sustentable y el Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto. Ushuaia, Argentina. 7 pp más anexos. [in Spanish with English abstract]

Valenzuela, A.E.J., Anderson, C.B., Smith, L.K.O., Guerrero, F. (2017). Estudios preliminares de huillín (Lontra provocax) en la Reserva Natural Silvestre Isla de los Estados, Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. XXX Jornadas Argentinas de Mastozoología. Bahía Blanca, Argentina. [in Spanish]

Valenzuela, A.E.J., Claverie A.Ñ., Anderson, C.B. (2021). El huillín (Lontra provocax) en Península Mitre (Tierra del Fuego, Argentina): un refugio para la conservación de esta nutria endémica amenazada. Jornadas Argentinas de Mastozoología, E-JAM. [in Spanish]

Valenzuela, A.E.J., Raya Rey, A., Fasola, A., Schiavini, A. (2013). Understanding the inter-specific dynamics of two co-existing predators in the Tierra del Fuego Archipelago: the native southern river otter and the exotic American mink. Biological Invasions. 15: 645-656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-012-0315-9

Résumé: Nouveaux Enregistrements de la Population Marine de Loutre du Chili Lontra Provocax : Confirmation de la Présence de l’« Huillín » sur la Péninsule de Mitre, Tierra Del Fuego, en Argentine

La loutre du Chili (Lontra provocax), connue sous le nom de l’Huillín en espagnol, est une espèce de loutre en voie de disparition endémique en Patagonie. L’Argentine compte deux populations séparées de 1.500 km : l’une d’eau douce dans le nord de la Patagonie et l’autre marine, côtière dans la province de Tierra del Fuego. Cette dernière population a été classée en danger critique d’extinction et ne présente jusqu’à présent que deux sous-populations stables à l’intérieur des aires protégées (parc national Tierra del Fuego et réserve provinciale de l’île de Staten). Plusieurs signalements sporadiques de cette espèce étaient connus dans la péninsule de Mitre (Tierra del Fuego), une région difficile d’accès. Le but de cette étude était d’évaluer la situation de la loutre du Chili dans la péninsule de Mitre. En 2018, 2021, 2022 et 2023, nous avons parcouru de manière systématique les côtes sud de la région (la seule ayant un habitat correct) et avons recherché des indices de présence de loutres (par exemple : épreintes, pistes, tanières). De plus, des pièges photographiques ont été installés dans des zones à forte activité. Nous avons réalisé de nouveaux enregistrements et confirmons également la présence durable de l’espèce dans la région. Les enregistrements de pièges photographiques confirment aussi la présence tout au long de l’année et la première confirmation connue de reproduction. Par ailleurs, des espèces introduites, comme le vison d’Amérique (Neogale vison) et les chiens errants (Canis lupus familiaris) qui ont été identifiés, constituent des menaces potentielles pour la loutre. Nous pensons que cette preuve de la présence de l’Huillín dans la péninsule de Mitre implique la présence d’une sous-population stable, ce qui signifierait également que la péninsule de Mitre représente un corridor biologique potentiel entre l’île de Staten et le reste de l’archipel.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Nuevos Registros para la Población Marina de Huillín (Lontra provocax): Confirmando la Presencia de esta Nutria en Península Mitre, Tierra Del Fuego, Argentina.

El huillín (Lontra provocax), una nutria endémica de Patagonia en peligro de extinción, presenta en Argentina dos poblaciones separadas por 1.500 km: una dulceacuícola en Patagonia norte, y una costera en la provincia de Tierra del Fuego (TDF). Esta última fue categorizada como en peligro crítico, y hasta ahora sólo presentaba dos subpoblaciones estables en áreas protegidas (Parque Nacional Tierra del Fuego y la Reserva Provincial Isla de los Estados). Varios registros esporádicos de esta especie habían sido reportados en Península Mitre (TDF), un área de díficl acceso. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar el estado de los individuos de huillín en Península Mitre. En 2018, 2021, 2022 y 2023, muestreamos sistemáticamente las costas sur de esta área (las únicas con hábitat adecuado), en búsqueda de signos que confirmaran la presencia de la nutria (e.g., fecas, huellas, madrigueras). Además, se colocaron cámaras trampa en las áreas con mayor nivel de actividad. Se confirmaron nuevos registros y también la presencia estable de la especie en esta área. Las cámaras también confirmaron la presencia a lo largo de todo el año y las primeras actividad reproductivas. También se identificaron especies introducidas como el visón americano (Neogale vison) y perros asilvestrados (Canis lupus familiaris), las cuales son amenazas potenciales para la nutria. Consideramos que esta evidencia de presencia de huillín en Península Mitre demuestra la existencia de una subpoblación estable, lo cual implica que esta área representaría un potencial corredor biológico entre Isla de los Estados y el resto del archipiélago.

Vuelva a la tapa