IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Volume 42 Issue 4 (August 2025)

Citation: Moreno Barrera, P., Ramírez-Bravo, O.E., Hernandez-Romero, P., and Garabana Quintana, B. (2025). Relative Abundance and Habitat Use of the Neotropical Otter (Lontra annectens) in the Cuichat River, Central México. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 42 (4): 186 - 193

Relative Abundance and Habitat Use of the Neotropical Otter (Lontra annectens) in the Cuichat River, Central México

Paola Moreno Barrera1, Osvaldo Eric Ramírez-Bravo2*, Pablo Hernandez-Romero3,4, and Bernardo Garabana Quintana5

1Instituto Tecnológico Superior de Zacapoaxtla Puebla, Carretera Acuaco - Zacapoaxtla Km. 8, Col. Totoltepec, Zacapoaxtla Puebla, Mexico

2Centro de Agroecología, Instituto de Ciencias, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. Edificio Val 4, Eco campus Valsequillo, Carretera Puebla-Tetela, San Pedro, ZIP CODE: 72960 Zacachimalpa, Mexico

3Laboratorio de Biodiversidad y Cambio Global (LABIOCG), Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Tlalnepantla de Baz, 54090, México

4IUCN Species Survival Commission, Otter Specialist Group, Rue Mauverney, 28, 1196 Gland, Switzerland

5Motocle A. C., Avenida Maximino Ávila Camacho 1019 - 9, Barrio de Santiago Xicotenco, San Andrés Cholula, Puebla, 73240, Mexico

*Corresponding Author Email: osvaldoeric.ramirez@correo.buap.mx

Received 30th May 2025, accepted 18th July 2025

Abstract: The eastern-central region of Mexico has very few reports on the presence of the northern neotropical otter (Lontra annectens). In this work, we determined the relative abundance and habitat use of L. annectens in the Cuichat River in Cuetzalan, Puebla. We followed a 16 km river branch that we traveled once a month from September 2012 to February 2013. In each descent, we identified sites with otter presence, signs of presence such as faeces, latrines, tracks, feeding places, and dens. We estimated the density of usage of latrines along the river. We analyzed seven habitat variables that were evaluated using a χ2 analysis for habitat use. We obtained 31 sites with otter presence, with a relative abundance of 0.32 otters/km. When anthropogenic activity was absent, we found that otters were more active and occupied more shelters regardless of whether the site presented steeper slopes or abundant tree cover. Knowing the variables preferred by otters will allow us to make informed decisions to generate conservation programs related to the species in the Cuichat River, which can be applied to other areas occupied by the species.

Keywords: Cuetzalan, distribution, conservation, Mustelid, Puebla.

INTRODUCTION

One approach to habitat conservation is to utilize existing carnivores as flagship species to promote habitat protection, leveraging their specific requirements and position as top predators (Sergio et al., 2008). However, there is little information available on the ecological variables that affect them (Eizirik et al., 2001) and their dispersal capabilities (Waser et al., 2001), making planning conservation and management programs difficult.

This is the case of the neotropical otter (L. annectens), a species for which there is a surprising lack of ecological information before the fragmentation of its habitat (Macías-Sánchez and Aranda 1999). Another important situation is that new genetic evidence split the neotropical otter into two species, the formerly denominated L. longicaudis and the newest denomination of L. annectens (De Ferran et al. 2024), therefore, studies on L. longicaudis annectens must be adapted to fit the new classification.

Furthermore, modeling L. annectens distribution at the catchment level is difficult due to the need for precise information on the characteristics of the river. Several studies have determined the distribution of the ecologically similar species Lontra canadensis in Mexican rivers depends low slopes and riparian vegetation availability (Carrillo-Rubio and Lafón, 2004; Cirelli, 2005; Gallo-Reynoso et al., 2019), the presence of slopes (Carrillo-Rubio and Lafón, 2004; Hernández-Romero, 2011), and the amount of dissolved oxygen, and water quality (Macías-Sánchez, 2003). Thus, otter density seems to be related to habitat productivity (Guerrero et al, 2013), and abundance of prey (Gallo-Reynoso et al., 2019); varying from 0.34 otters per km in semi-arid habitats (Gallo-Reynoso,, 1996) to 2.45 otters per km and 6.26 otters per km in tropical areas (Macías-Sánchez, 2003). Due to these factors, the species is considered a reliable bioindicator for habitat quality modifications that could negatively impact its persistence and density in a given river (Owen, 1971; Malanson, 2009; Duque-Dávila et al., 2013).

Since this species is widely distributed in Mexico, it is necessary to produce information on the different habitats where it can be found. This is a priority in highly threatened habitats, such as the mountainous cloud forest, which has a restricted distribution in the country and has been drastically reduced (Challenger and Caballero, 1998). In addition, it is necessary to determine the factors that affect its presence in this habitat as it can serve as a reference for other similar areas. The Eastern Central Mexico presents this opportunity, as it has fragments of the cloud forests habitat, and the otter is present in several of these areas. Our main objective is to understand the otter ecology and distribution in these areas to improve conservation and management programs for the species, using as an example the basin of the Cuichat River.

METHODS

Study Area

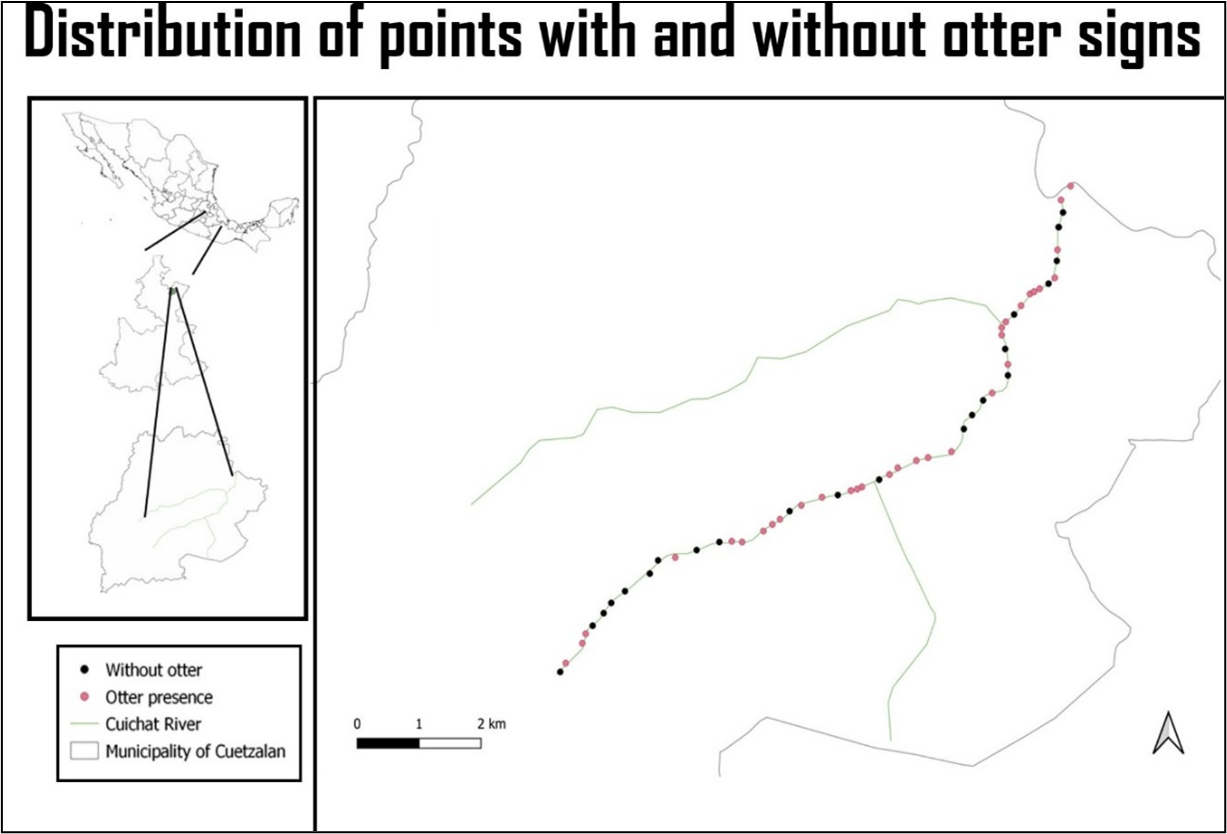

The Cuichat River is found in the municipality of Cuetzalan del Progreso, State of Puebla, in Eastern Central Mexico. The municipality has a semi-warm-subhumid climate, rainfall is present throughout the year, with the highest precipitation values at the national level, exceeding 4,000 mm of annual average (Vázquez, 1990). The river is 16 kilometers long and has a maximum height of 1,012 masl, descending to 157 masl (INEGI, 2009) (Fig. 1).

Fieldwork

We conducted a total of six field trips with a duration of six days each, per month, from September 2012 to February 2013, getting a total of 36 days at the end of the study. When weather conditions allowed, we covered as much of the 16 km area along the river as possible over the six days. Weather patterns were important since during the rains the terrain becomes unstable, and the level of the river increases greatly, making it dangerous for researchers. Also it has to be clear that there is a seasonal vias that has to be address, changes on the level of the river due to the rain may wash away otter tracks or completely force otters to move to other sites, as sites like shelters may flood; so future research should consider this factors.

During the field trips of January and February we walked the whole river, in November and December we covered 12 km, and during September and October, we only covered 8 km due to river conditions due to the rainy season. During each trip, we looked for L. annectens sites by identifying their presence through faeces, latrines, footprints, feeders, and probable burrows using Aranda's (2000) field guide. Burrows are cavities near water formed by rocks or by tree roots. usually, otter burrows have two entrances, one from the water and the other from dryland; to completely define them as occupied by otters should have some faeces inside (Macías-Sánchez, 2003). Feeders are sites where otters usually feed, and it is possible to find remains of eaten prey and otter faeces. Latrines are sites with the presence of faeces as well as other secretions like urine; these sites are used by otters to mark territory and as a means of communication (Gallo-Reynoso et al, 2019).

We recorded environmental variables within a radius of 25 m at each site since most monitoring projects by CONANP (Commission on Protected Natural Areas) record variables using these measures; this way, data can be comparable to similar studies by CONANP. While looking for and recording the presence of otter tracks at sites during the six-day field trip. In cases of sites with more than one sign, a circumference that englobed all signs was considered as a reference to measuring the variables within a 25 m radius. In the study area, human activities consisted of livestock production and agriculture, which are common around the river. We also registered indications of urbanization (presence of roads, crop fields, livestock, and houses), which were measured by their presence/absence within the established 25 m radius, as a preliminary evaluation of human impact on otter populations in the Cuichat river, as further studies are required in the future.

Habitat Characteristics

We determined habitat use by describing seven environmental variables: 1) Vegetation type (arboreal, shrubby, mixed, null), 2) Riverbed characteristics (sandy, stony, rocky), 3) shelter availability, 4) anthropogenic activity (presence, absence), 5) trail location (in the middle of the river, in the shore), 6) riverbank characteristics (slope, sandy shore, stony shore, rocky shore) and 7) Channel characteristics (high-deep zone, medium-high depth zone, medium-low depth zone, low-depth zone). Vegetation type is among the most important characteristic, since it directly influences otter habitat preferences (Mayor-Victoria and Botero-Botero, 2010), in “observed sites” which were those with otter signs (faeces, footprint, burrow), and in “expected sites” which were sites obtained by setting and numbering squares along the river and using a random number generator with Microsoft Excel 2010 to select some of this squares. If any of these random sites for habitat characterization fell near an otter site, it was moved 50 m downstream, obtaining a total of 53 sites; the number was just based on the maximum number of points that could be established along the river, avoiding sites with previously confirmed otter presence. We compared results for both sites using a χ2 analysis (Hernández-Romero, 2011). In case there was a significant difference, we used a Bonferroni confidence interval test with a 95% confidence to determine differences among values. We selected the Bonferroni analysis since not all variables were measurable, and it is a recommended confidence interval for comparing availability and usage (Byers et al., 1984). Furthermore, it helped to make our results comparable with previously published data.

RESULTS

We found 31 sites with otter signs along the 16 km traveled of the Cuichat River, with 25 sites presenting one or more faeces and 6 sites with footprints. The highest number of tracks was obtained on the riverbank at the lower altitudes of 157 masl. The lowest presence of tracks was found at higher altitudes of 1,012 masl (Figure 1).

The results showed there are significant differences between the expected and observed values of all variables (Table 1). Bonferroni intervals explained that the species prefers areas with low slopes, pools, rocky beds, good tree cover, high shelter availability, and little anthropogenic activity.

The expected values presented in Table 1, obtained from sites without signs of otters, serve as a control for comparison with the sites that exhibit signs of otters.

DISCUSSION

This study in mountain cloud forests can help identify priority conservation zones throughout this ecosystem. The obtained results are like those obtained through other sampling methods, such as photo-trapping, the most widely used technique for population and habitat use studies of otters in other regions of Mexico (Gallo-Reynoso et al. 2019).

The results on habitat use show that despite differences in habitat, the characteristics sought by the species are like those previously recorded in other sites. An example of this is the use of large rocks on the banks of rivers as latrines (Mayor-Victoria and Botero-Botero, 2010), the use of slopes as resting, shelter, and breeding sites (Cirelli, 2005; Hernández-Romero, 2011). Similarly, there was a preference for sites with rocky banks because they are associated with pools and deep areas of the river, indicating a higher probability of prey availability, mainly during the dry season (Gallo-Reynoso, 1996; Cirelli 2005; Hernández-Romero, 2011). In addition, we observed that, as in other areas, the otter prefers areas with extensive vegetation cover (Gallo-Reynoso, 1996; Calmé and Sanvicente, 2009), although the species seems to prefer shrubs rather than dense tree populations.

Regarding human presence, other studies have shown that it is not a factor that affects the presence of the otters (López-Martín et al., 1998; Briones-Salas et al., 2008), but only when it is low intensity of use of common areas. However, sewage discharge and garbage deposits can cause otters to move to sites with better water quality (Gallo-Reynoso, 1996; Macías-Sánchez, 2003; Hernández-Romero 2011). As has been observed with otter tracks have been found in areas without human activities, although some sites with slight human presence reported higher densities of otters than completely undisturbed areas, showing that possible anthropogenic activity may benefit otter populations slightly, being an interesting contrast to what previous studies report. However, it is necessary to determine the effects of human activity on otters' presence. Still, the results obtained helped us determine some key preferences in the habitat for neotropical otters: preferred vegetation coverage, presence of slopes and large rocks and none or slight human presence

Ethics Statement: We applied indirect methods, so no permits were required; however, we followed the ethical and legal standards in Mexico, including asking for permission from local authorities.

REFERENCES

Aranda, J. M. (2000). Huellas y otros rastros de los mamíferos grandes y medianos de México [ Footprints and other traces of large and medium-sized mammals of Mexico]. Instituto de Ecología (INECOL). Comisión Nacional para el conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO). México. 121-137. ISBN: 9789687863627

Briones-Salas, M., Cruz, J., Gallo-Reynoso, J. P. And Sánchez-Cordero, V. (2008). Abundancia relativa de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) en el río Zimatán en la costa de Oaxaca, México [Relative abundance of the Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis annectens) in the Zimatán River on the coast of Oaxaca, Mexico]. Pp. 355-376 in Lorenzo, C., E. Espinoza and J. Ortega, (Eds.), Avances en el estudio de los mamíferos de México II [Advances in the Study of Mexican Mammals II] . México D.F.: Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología, A.C. https://mamiferosmexico.org/books/Avances_Estudio_Mamiferos_Mexico_II.pdf

Byers, C.R., Steinhorst, R. K., and Krausman, P. R. (1984). Clarification of a Technique for Analysis of Utilization-Availability Data. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 48 (3): 1050-1053 https://doi.org/10.2307/3801467

Calmé, S., and M. Sanvicente. (2009). Distribución, uso de hábitat y amenazas para la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens): un enfoque etnozoológico.[ Distribution, habitat use, and threats to the Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis annectens): an ethnozoological approach.] In: Espinoza A. J., G. A. Islebe and H. A. Hernández (Eds.). (2009). El Sistema Ecológico de la Bahía de Chetumal/Corozal: Costa Occidental del Mar Caribe [The Ecological System of Chetumal/Corozal Bay: Western Coast of the Caribbean Sea]. El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR).

Carrillo-Rubio, E and Lafón, A. (2004) Neotropical River Otter Micro-Habitat Preference In West-Central Chihuahua, Mexico. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 21(1): 10 – 15 https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume21/Carillo_Rubio_Lafon_2004.html

Challenger, A. and Caballero, J. (1998). Utilización y conservación de los ecosistemas terrestres de México: Pasado, presente y futuro [Utilization and conservation of Mexico's terrestrial ecosystems: Past, present, and future]. CONABIO-Instituto de Biología, UNAMA grupación Sierra Madre, México. 848. ISBN: 9789709000023

Cirelli, V. V. (2005). Restauración ecológica de la cuenca Apatlaco-Tembembe. Estudio de caso: Modelado de la distribución de la nutria Lontra longicaudis annectens [Ecological restoration in the Apatlaco-Tembembe basin: a modeled case study of the distribution of the river otter, Lontra longicaudis annectens]. M. Sc. Thesis., Universidad Autónoma de Morelos, Morelos, México. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14330/TES01000347296

De Ferran, V., H. V. Figueiró, C. S. Trinca, P. C. Hernández-Romero, G. P. Lorenzana, C. Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, K. Koepfli, and E. Eizirik. (2024). Genome-wide data support recognition of an additional species of neotropical river otter (Mammalia, Mustelidae, Lutrinae). Journal of Mammalogy, 105(3): 534-542. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyae009

Duque-Dávila, D. L., E. Martínez-Ramírez , F. J. Botello-López, and V. Sánchez-Cordero. (2013). Distribución, abundancia y hábitos alimentarios de la nutria (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897) en el Río Grande, Reserva de la Biosfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán, Oaxaca, México [Distribution, abundance and feeding habits of the otter (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897) in the Rio Grande, Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve, Oaxaca, Mexico]. Therya, 4(2): 281-296. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-13-128

Eizirik, E., J. H. Kim, M. Menotti-Raymond, P. G. Crawshaw, S. J. O’Brien, and W. E. Johnson. (2001). Phylogeography, population history and conservation genetics of jaguars (Panthera onca, Mammalia, Felidae). Molecular ecology. 10(1):65–79. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294X.2001.01144.x

Gallo-Reynoso, J. P. (1996). Distribution of the Neotropical River Otter (Lutra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897) in the Rio Yaqui, Sonora, Mexico. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 13 (1): 27 – 31 https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume13/Gallo_1996.html

Gallo-Reynoso, J. P., S. Macías-Sánchez, V. A. Nuñez-Ramos, A. Loya, I. D. Barba-Acuña, J. Guerrero-Flores, G. Ponce-García, A. A. Gardea-Bejar. (2019). Identity and distribution of the Nearctic otter (Lontra canadensis) at the Rio Conchos Basin, Chihuahua, México. Therya 10(3):243-253. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-19-894

Guerrero-Flores, F. J., S. Macías-Sánchez, V. Mundo-Hernández and F. Méndez-Sánchez. (2007). Ecología de la nutria (Lontra longicaudis) en el municipio de Temascaltepec, estado de México: estudio de cason [Ecology of the otter (Lontra longicaudis) in the municipality of Temascaltepec, State of Mexico: a case study]. Therya, 4(2): 231-242. https://doi.org/10.12933/therya-13-127

Hernández-Romero, P. C. (2011). Abundancia poblacional y preferencia de hábitat de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897) en el Río Grande, Cuicatlán, Oaxaca [Population abundance and habitat preference of the Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897) in the Río Grande, Cuicatlán, Oaxaca]. M. Sc. Thesis. Instituto de Ecología (INECOL), México, Veracruz, Mexico.

INEGI. (2009). Prontuario de información geográfica municipal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos [Municipal Geographic Information Handbook of the United Mexican States]. https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=702825293109

López-Martín, J.M., J. Jiménez, and J. Ruiz-Olmo. (1998). Caracterización y uso del hábitat por parte de la nutria (Lutra lutra) en un río de tipo mediterráneo. Galemys 10:175-190. https://gruponutria.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/1720-20lf3pez-martedn20175-190.pdf

Macías-Sánchez, S. (2003). Evaluación del hábitat de la nutria neotropical (Lontra longicaudis Olfers, 1818) en dos ríos de la zona centro de Veracruz, México [Habitat assessment of the Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis Olfers, 1818) in two rivers in central Veracruz, Mexico] M. Sc. Thesis. Instituto de Ecología (INECOL), Veracruz, México. https://www.academia.edu/106815725/Evaluaci%C3%B3n_del_h%C3%A1bitat_de_la_nutria_neotropical_Lontra_longicaudis_Olfers_1818_en_dos_r%C3%ADos_de_la_zona_centro_del_Estado_de_Veracruz

Macías-Sánchez, S., and M. Aranda. (1999). Análisis de la alimentación de la nutria Lontra longicaudis (Mammalia: Carnivora) en un sector del río Los Pescados, Veracruz, México [Analysis of the diet of the otter Lontra longicaudis (Mammalia: Carnivora) in a sector of the Los Pescados River, Veracruz, Mexico]. Acta Zoológica Mexicana Nueva Serie 76: 49–57. https://doi.org/10.21829/azm.1999.76761699

Malanson, G. P. (2009). Species dynamics. Chapter 6 pp 178-203 in Malanson, G.P. Riparian Landscapes. Cambridge Studies in Ecology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN:

9780511565434 https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511565434

Mayor-Victoria, R., and A. Botero-Botero. (2010). Uso del hábitat por la nutria neotropical Lontra longicaudis (Carnívora: Mustelidae) en la zona baja del río Roble, alto Cauca, Colombia [Habitat use by the Neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora: Mustelidae) in the lower Roble River, Upper Cauca, Colombia]. Boletín Científico Museo de Historia Natural, 14:121-130 http://ref.scielo.org/jfy727

Owen, O. S. (1971). Natural resource conservation. 2 ed. The Macmillian Company, New York. Pp 457-460. ISBN: 9780023900204

Sergio, F., T. Caro, D. Brown, B. Clucas, J. Hunter, J. Ketchum, K. McHugh, and F. Hiraldo. (2008). Top Predators as Conservation Tools: Ecological Rationale, Assumptions, and Efficacy. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 39: 1–19.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173545

Vázquez, G. J. H. (1990). El conocimiento ecológico en las prácticas agrícolas tradicionales entre los totonacos de una comunidad de la Sierra Norte de Puebla [Ecological knowledge in traditional agricultural practices among the Totonac people of a community in the Sierra Norte of Puebla]. Degree Thesis, Facultad de Filosofía y letras. Colegio de Geografía. UNAM. México. https://tesiunamdocumentos.dgb.unam.mx/pmig2017/0115602/0115602.pdf

Waser, P.M., C. Strobeck, and D. Paetkau. (2001). Estimating inter-population dispersal rates. Chapter 22 pp 484–497 in Gittleman JL, Funk SM, Macdonald DW, Wayne RK, (Eds). Carnivore conservation. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge. ISBN: 978-0521662321

Résumé: Abondance Relative et Utilisation de l’Habitat de la Loutre Néotropicale (Lontra annectens) dans la Rivière Cuichat, au Centre du Mexique

La région Centre Est du Mexique possède très peu de données sur la présence de la loutre néotropicale du nord (Lontra annectens). Dans ce travail, nous avons déterminé l’abondance relative et l’utilisation de l’habitat de L. annectens le long de la rivière Cuichat à Cuetzalan, dans l’État de Puebla. Nous avons parcouru un bras de rivière de 16 km que nous avons prospecté une fois par mois de septembre 2012 à février 2013. À chaque descente, nous avons identifié des lieux de présence de loutres, ainsi que des indices de présence tels que des épreintes, des latrines, des traces, des aires d’alimentation et des catiches. Nous avons estimé la densité d’utilisation des latrines le long de la rivière. Nous avons analysé sept variables d’habitat, qui ont été évaluées par une analyse du χ2 de l’utilisation de l’habitat. Nous avons obtenu 31 sites de présence de loutres, avec une abondance relative de 0,32 loutre/km. En l’absence d’activité anthropique, nous avons constaté que les loutres étaient plus actives et occupaient davantage d’abris, liés à la présence de pentes raides ou à un couvert forestier abondant. Connaître les variables de prédilection des loutres nous permettra de prendre des décisions judicieuses afin de générer des programmes de conservation liés à l’espèce de la rivière Cuichat. Ces programmes pourront être appliqués à d’autres zones occupées par l’espèce.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Abundancia Relativa y Uso de Hábitat de la Nutria Neotropical (Lontra annectens) en el Río Cuichat, en el Centro de México

La zona centro-oriental de México presenta muy pocos reportes de presencia de nutria neotropical (Lontra annectens). En este estudio, determinamos la abundancia relativa y uso de hábitat de L. annectens en el Río Cuichat en Cuetzalan, Puebla. Recorrimos un brazo del río de 16 km de largo una vez al mes durante el periodo de septiembre 2012 a febrero 2013. En cada descenso identificamos sitios con presencia de nutrias, como lo son heces fecales, letrinas, rastros, alimentadores y madrigueras. Estimamos la densidad de uso de letrinas a lo largo del río. Analizamos siete variables de hábitat que fueron evaluadas usando análisis χ2 para uso de hábitat. Obtuvimos 31 sitios con presencia de nutria, con una abundancia relativa de 0.32 nutrias/km. Cuando hubo ausencia de actividad antropogénica, descubrimos que las nutrias son más activas y ocupan más madrigueras, independientemente de si el sitio presentaba pendientes pronunciadas o cobertura abundante de árboles. Conocer las variables preferidas por las nutrias, nos permitirá tomar decisiones mejor informadas para generar programas de conservación para la especie en el Río Cuichat, qué pueda ser aplicado a su vez a otras áreas ocupadas por esta especie.

Vuelva a la tapa