IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Volume 36 Issue 1 (January 2019)

Citation: Medina-Barrios, O and Morales-Betancourt, D (2019). Notes on the Behaviour of Neotropical River Otter (Lontra longicaudis) in Palomino River (La Guajira, Colombia). IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 36 (1): 34 - 47

Notes on the Behaviour of Neotropical River Otter (Lontra longicaudis) in Palomino River (La Guajira, Colombia)

Oscar Medina-Barrios1 and Diana Morales-Betancourt2

1 Animal Care Coordinator, Fundación Botánica y Zoológica de Barranquilla, Cl. 77 #68-40 Barranquilla, Colombia, e-mail o.medina@zoobaq.org

2 Project coordinator, Omacha foundation. Corresponding author e-mail: dianamoralesb@yahoo.com

Received 8th October 2018, accepted 23rd January 2019

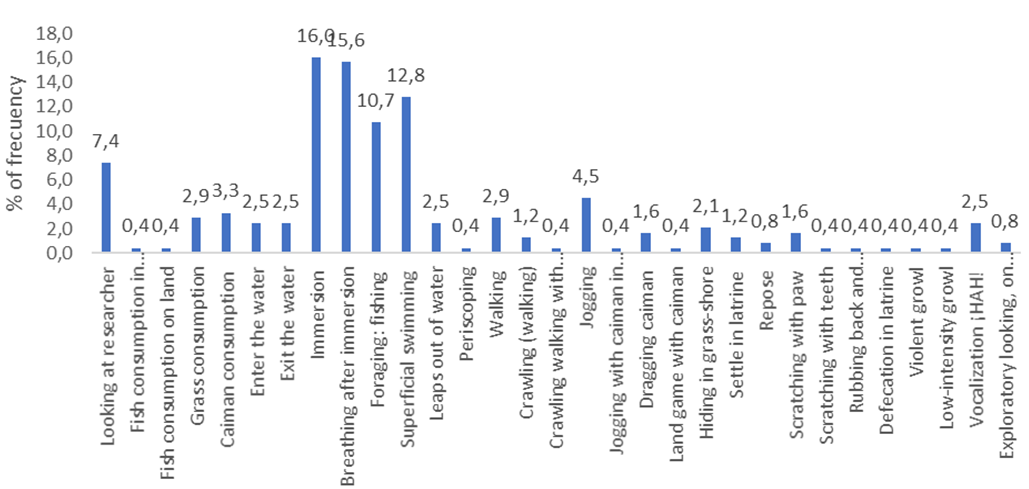

Abstract: The Neotropical river otter is a semiaquatic mammal that occupies a large geographic distribution. It habitually defecates in conspicuous areas on land; these indirect indicators are the focus of most of the studies that involve them, but little is known about species’ behaviour. In Colombia, the species is considered as Vulnerable and in the Northern area of the country (La Guajira) there are no studies focussed on it. In this paper, observations on L. longicaudis behaviour in the wild were made, as a first approach to it, while occurrence studies were carried out in the area. Observations were made in 2015 during the dry or non-raining season (February), in the middle and lower course of the Palomino River. Five observation sites were established along the river, and the observation method implemented was ad libitum sampling. As a result, a total of 31 different behaviours were recorded, from which immersion, breathing after immersion, superficial swimming and foraging were most frequent at 16%, 15.6%, 12.8%, and 10.7% respectively.

Keywords: Neotropical otter, otter behavior, Colombia endangered species, aquatic mammals.

INTRODUCTION

The Neotropical river otter Lontra longicaudis (Olfers, 1818), member of the Mustelidae family, is a semiaquatic mammal that occupies a wide geographical distribution, occurring from Mexico to the north of Argentina (Waldemarin and Colares, 2000; Arellano et al., 2012). The species is found in rivers and water bodies that can be fresh, marine or brackish water (Kasper et al., 2004). They are abundant in rivers where the riparian vegetation is dense and the root of the trees form galleries. Rivers with this kind of vegetation are usually clear water, flanked by large rocky blocks (Parera, 1996; Lariviére, 1999; Casariego-Madorell et al., 2006). Recently non-invasive molecular approaches estimated a linear density of one otter per km from in an Atlantic Forest area in Southern Brazil (Trinca et al., 2013) and radio-telemetry in a mangroves area showed a movement of 2.6 km (Nakano-Oliveira et al., 2004).

In general, they have a habit of defecating in conspicuous places of the aquatic body, (Wemmer et al., 1996; Kasper et al., 2004) or in the adjacent terrestrial ecosystem. This behavior is the focus of most of the studies that involve them, and are being used for the definition of areas of occurrence (Chehébar, 1985; Chehébar et al., 1986; Blacher, 1987; Kasper et al., 2004) and diet studies (Beja, 1991; Brezinski et al., 1993; Passamani and Camargo, 1995; Pardini, 1998; Quadros and Monteiro-Filho 2000; Quadros and Monteiro-Filho, 2001; Kasper et al., 2004). However, the social behavior of this species has been slightly studied (Gorman and Trowbridge, 1989; Kasper et al., 2004).

This species is currently included in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora- CITES Appendix I (2017), it is catalogue as Vulnerable in the Red List of Threatened Species of Colombia (Rodriguez et al., 2006), and is Near Threatened on a global scale by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature - IUCN (Rheingantz and Trinca, 2015). Nevertheless, their populations have declined due to the influence of anthropogenic activities such as hunting (Morales-Betancourt and Medina Barrios, 2018), spilling of industrial, and urban waste, drainages, intensive water extraction, high concentrations of pollutants (Gallo-Reynoso 1989; Foster-Turley et al., 1990; Sierra and Vargas 2002; Cirelli, 2005; Arellano et al., 2012), legal and illegal mining (industrial and artisanal), that modify the physical and chemical conditions of the water, the riverbeds and increase of deposits of heavy metals (Trujillo et al., 2013). In addition, other risk factors such as parasites, diseases, natural deaths, among others exists (Arellano et al., 2012). In general, due to its strong dependency of an adjacent terrestrial environment to the water bodies, river otters can be affected for negative changes of the margins of the tributaries (Foster-Turley et al., 1990; Quadros and Monteiro-Filho, 2002; Kasper et al., 2004; Santos et al., 2012; Trujillo et al., 2013).

As a contribution to the species, La Guajira’s Environmental Authority – Corpoguajira subscribe with Omacha Foundation the contract “Otter (Lontra longicaudis) conservation at the La Guajira department, with focus on Forest Protective Reserve Montes de Oca” that focused on studies on occurrence and specific threats to the species in the area, as well as implementation of community awareness activities. Final objective of these studies were, to serve as inputs for the elaboration of the Conservation management plan of the Neotropical otter (L. longicaudis) in La Guajira.

METHODOLOGY

Area of study

The Palomino River is located between Magdalena and La Guajira, the Northern region of Colombia. Palomino headwater is 4600 meters above sea level in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and main course is about 70 km length until its mouth in the Caribbean Sea (Neuta et al., 2017). The river water is extremely transparent, and people use the river for different activities as recreational (tubing and swimming) (Figure 1), harpoon fishing, clothes watching and sand and gravel extraction. Palomino beach is one of the emerging destinations for millennial tourist in Colombia since it has a snow mountain view and many trails that connect to the indigenous communities, in front of it the sea with surfing waves and hostels by the beach were the river ends. Although, no tourism development plan or tourism land use order had been implemented yet.

During the dry season of the year 2015 (February), sampling was carried out in the middle and low areas of the Palomino River (municipality of Dibulla, La Guajira department) by the riverbeds and banks (Figure 2), for a total of 3 km segmented in six transects. Latrines were identified and those with fresh faeces were selected to locate, close by, sighting station to increase possibility of direct L. longicaudis observation. Methodology for detection through direct observation was implemented (Anguera, 1986), with an ad libitum method, annotating the behaviour observed over a designated period of time or frequency (Gras et al., 1990).

Five sighting stations were established, from P1 to P5, where P1 was the closest one to the river mouth and P5 the farthest from the sea. GPS references are shown in Table 1.

The observation was made for a period of nine days, with a sampling effort 41 hours at not less than 20 meters from the latrines, with 143,07 minutes of behaviour observations.

An observational chart was made for each sighting of L. longicaudis, specifying time and activity executed and grouped the behaviours found in categories, as implemented by Duplaix (1980) for Giant river otter (Pteronura brasiliensis). There was more observation time at some points given the better accessibility.

RESULTS

Observation stations methodology for the direct observation using an ad libitum sample, made possible to register L. longicaudis four times, in four different days, three of them in the same latrine, observation station P1 located in the Global Positioning System- GPS Coordinates N 11o 14’ 54.7”; W 073o 34’ 05.4”. Fourth sighting occurred during the morning in observation station P2, GPS Coordinates N 11 o 14 ' 46.6 "; W 073° 34’ 04.1”, which is approximately 200 m from observation station P1.

RESULTS

The observation station methodology for the direct observation using an ad libitum sample resulted in recording L. longicaudis four times, on four different days. Three of the records were at the same latrine, at observation station P1, located at GPS Coordinates N 11o 14’ 54.7”; W 073o 34’ 05.4”. The fourth sighting occurred during the morning at observation station P2, GPS Coordinates N 11 o 14 ' 46.6 "; W 073° 34’ 04.1”, which is approximately 200 m from observation station P1.

In these four events, 31 different behaviours were recorded, of which immersion, respiration after immersion, surface swimming and foraging occupied the highest rate of frequencies with 16%, 15.6%, 12.8%, and 10.7% respectively (Figure 3). To group behaviors according to common characteristics (Table 2), variables described by Duplaix (1980) for Pteronura brasiliensis were used, since behavioural descriptors for L. longicaudis do not exist. Behaviors were clustered in groups and subgroups by Duplaix (1980) in order to facilitate the reading and to improve the understanding of the relations between behaviours.

| Table 2: Groups, subgroup and behaviour unit observed in wild L. longicaudis in Palomino river, La Guajira, Colombia. | ||||

| Characteristics of the behaviours* | Behaviour | % of frequency | ||

| Group | Subgroup | |||

| Senses | Observation | Looking at researcher (Figure 4) |

7.4 | |

| Maintenance activities | Feeding | Fish consumption in surface swimming | 0.4 | |

| Fish consumption on land | 0.4 | |||

| Grass consumption | 2..9 | |||

| Caiman consumption (Figure 5) |

3.3 | |||

| Locomotion | Aquatic locomotion | Enter the water | 2.5 | |

| Exit the water | 2.5 | |||

| Immersion | 16 | |||

| Breathing after immersion | 15.6 | |||

| Foraging: fishing (Figure 6) |

10.7 | |||

| Superficial swimming (Figure 7) | 12.8 | |||

| Leaps out of water | 2.5 | |||

| Periscoping | 0.4 | |||

| Terrestrial locomotion and postures | Walking | 2.9 | ||

| Crawling (walking) | .1.2 | |||

| Crawling walking with caiman in mouth (Figure 8) | 0.4 | |||

| Jogging (Figure 9) | 4.5 | |||

| Jogging with caiman in mouth (Figure 10) | 0.4 | |||

| Dragging caiman (Figure 11) | 1.6 | |||

| Land game with caiman | 0.4 | |||

| Hiding in grass-shore | 2.1 | |||

| Settle in latrine

(Figure 12) |

1.2 | |||

| Comfort Activities | Resting and sleeping postures - Rest | Repose (Figure 13) | 0.8 | |

| Cleaning - Scratching | Scratching with paw (Figure 14) | 1.6 | ||

| Cleaning - Skin biting | Scratching with teeth | 0.4 | ||

| Cleaning – Rolling and rubbing | Rubbing back and abdomen (Figure 15) | 0.4 | ||

| Elimination - Defecation | Defecation in latrine | 0.4 | ||

| Social activities | Communication/Vocalization | Violent growl | 0.4 | |

| Low-intensity growl | 0.4 | |||

| /Communication/Investigation and alarm - Alarm | Vocalization ¡HAH! (Figure 16) |

2.5 | ||

| Investigation and alarm - Investigation | Exploratory looking, on land (Figure 17) |

0.8 | ||

| *Based on groupings made by Duplaix (1980) for P. brasiliensis. | ||||

In Figures 4 to 17, images of behaviours referred to in Table 2 are shown with descriptions.

DISCUSSION

From the observed behaviours, it was possible to identify juvenile spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus fuscus) being taken in riparian vegetaion on the riverbank (Medina-Barrios and Morales-Betancourt, 2015) and fish consumption in the water with the head raised out of the water, confirming that during the dry season in the lower Palomino river, this species behaves as an opportunistic predator, as had been previously documented in other areas of the continent.

In a 3 km length of river length, close to the active latrines, the most common behaviours were related to aquatic locomotion, and were only observed in the morning (from 6:58 am to 9:04 am). Tourist activity, such as tubing, occurs from 9 am to 6 pm. This could indicate that later in the day, the otters are engaged in other activities far from latrines, or it could be that human activities cause a reduction in activity, or temporal displacement to, for example, night time. Obviously, more behavioural studies are needed to complete the information on Neotropical otter habitat use in this type of rivers with the active presence of humans.

The environment of the latrine at which the four sets observations were made presented features that made it suitable (without being ideal) for the observing the activities of the otters, with bushes and herbaceous plants on the riverbank adjacent to water (Figure 2). This vegetation type was also reported by Santos and Reis (2012), and guaduales (Guadua angustifolia) vegetation was mentioned by Waldemarin (2004). For this reason, the conservation of bankside vegetation is crucial for the presence of the otter in the Palomino River.

Acknowledgements: The authors want to thank all the colleagues at the Omacha Foundation and at Corpoguajira; and the local community of Palomino, specially to Ms. Patricia Muñoz, for her hospitality, also the Afro Descendent Group Negro Mandela, Horticulture woman group of the Sierra, Union of Forest Savers of the Sierra, Group of turtle conservation, and the communities of the Neighborhood Sierrita; to all of you, thank you for your collaboration. Special thanks to Mr. Miguel Barrios from Riohacha, a kind adviser that transported us in this beautiful land of La Guajira. Many thanks to the Dr. Arno Gutleb for all his work in the IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin.

REFERENCES

Anguera, M. T. (1986). La investigación cualitativa. Educar, 10: 23-50. [In Spanish]

Arellano, E. Sánchez Núñez, E., Mosqueda Cabrera, M.A. (2012). Distribución y Abundancia De La Nutria Neotropical (Lontra longicaudis annectens) En Tlacotalpan, Veracruz, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana, 28 (2): 270-279. [In Spanish]

Beja, P.R. (1991). Diet of otters (Lutra lutra) in closely associated freshwater, barckish and marine hábitat in south-west Portugal. Journal of Zoology, 225: 141-152

Blacher C. (1987). Ocorrência e preservaçâo de Lutra longicaudis (Mammalia: Mustelidae) no litoral de Santa Catarina. Boletim de fundaçâo brasileira para conservaçâo da natureza, 22: 105-117. [In Portuguese]

Brezinski, M., Jedrezejewski, W., Jedrezejewska, B. (1993). Diet of otters (Lutra lutra) inhabiting small rivers in the Bialowieza National Park, eastern Poland. Journal of Zoology, 230: 495-501.

Casariego-Madorell, M.A., List, R., Ceballos, G. (2006). Aspectos básicos sobre la ecología de la nutria de río (Lontra longicaudis annectens) para la costa de Oaxaca. Revista Mexicana De Mastozoología, 10:71-74. [In Spanish]

Cirelli, V.V. (2005). Restauración ecológica en la cuenca Apatlaco-Tembembe. Estudio de caso: Modelado de la distribución de la nutria de río, Lontra longicaudis annectens. Tesis de Maestría en Ciencias Biológicas. Instituto de Biología. UNAM. México. [In Spanish]

CITES (2017). Appendices I, II and III. http://www.cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php.

Chehébar, C.E. (1985). A survey of the southern river otter Lutra provocax Thomas in Nahuel Huapi National Park, Argentina. Biological Conservation, 32: 299-307.

Chehébar, C.E., Gallur, A., Giannico, G., Gotelli, M.D., Yorio, P. (1986). A survey of the southern river otter Lutra provocax in Lanin, Puelo and los Alerces National Parks, Argentina, and evaluation of its conservation status. Biological Conservation, 38: 293-304.

Duplaix, N. (1980). Observations of the ecology and behavior of the giant river otter Pteronura brasiliensis in Suriname. Revue d'Écologie,: 34

http://hdl.handle.net/2042/55014.

Foster-Turley, P., Macdonald, S., Mason, C.F., (1990). (eds.) Otters: An action plan for their conservation. IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group, Gland, Switzerland. 126p.

Gallo-Reynoso, J.P. (1989). Distribución y estado actual de la nutria o perro de agua (Lutra longicaudis annectens Major, 1897) en la sierra Madre del Sur, México. Tesis, maestría Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México, D.F. 236 p.

Gorman, M. L., Trowbridge, B. J. (1989). The role of odour in the social lives of Carnivores, p. 57-88. In: Gittleman, J. L. (Ed.). Carnivore behaviour, ecology and conservation. New York, Cornell University Press, 620 p.

Gras, J.A., Anguera, M.T., Gómez, J. (1990). Metodología de la investigación en ciencias del comportamiento. Universidad de Murcia, 310 p. [In Spanish]

Harris, C.J. (1968). Otters: a study of the recent Lutrinae. Weinfield and Nicholson, London, 397 pp.

Kasper, C.B., Feldens, M.J., Salvi, J., Zanardi Grillo, H.C. (2004). Estudo preliminar sobre a ecología de Lontra longicaudis (Olfers) (Carnivora, Mustelidae) no Vale do Taquari, Sul do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Zoología. 21 (1): 65-72. [In Portuguese]

Lariviére, S. (1999). Lontra longicaudis. Mammalian Species, 609: 1-5.

Medina-Barrios, O.D., Morales-Betancourt, D. (2015). Evento de depredación de Caimán Crocodilus fuscus por Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora: Mustelidae) en el río Palomino, departamento de La Guajira, Colombia. Mammalogy Notes - Notas Mastozoológicas, 2 (1): 19-21. [In Spanish]

Morales-Betancourt, D., Medina Barrios, O.D. (2018). Notes on Neotropical Otter (Lontra longicaudis) hunting, a possible underestimated threat in Colombia. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 35(4): 196-202.

Nakano-Oliveira, E., Fusco, R., dos Santos, E.A.V., Monteiro-Filho, E.L.A. (2004). New information about the behavior of Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora: Mustelidae) by radio-telemetry. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull, 21(1): 31 - 35

Neuta, I., Reyes, C., Romero, L., Serpa, L., Vasquez, S. (2017). Cuenca hidrográfica río Palomino. Universidad del Magdalena, Facultad de Ingeniería, Programa de Ingeniería Ambiental y Sanitaria, Hidrología. Santa Marta-Colombia. [In Spanish]

Pardini, R. (1998). Feeding ecology of the neotropical river otter Lontra longicaudis in an Atlantic Forest Stream, south-eastern Brazil. Journal of Zoology 245:385-391.

Parera, A. (1993). The neotropical river otter Lutra longicaudis in Iberá lagoon, Argentina. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin, 8: 13-16.

Parera, A. (1996). Estimating river otter Lutra longicaudis population in Iberá lagoon using a direct sightings methodology. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin, 13:77-83.

Passamani, M., Camargo, S.L. (1995). Diet of the river otter Lontra longicaudis in Furnas Reservoir, soutu-eastern Brazil. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin, 12: 32-34.

Quadros, J., Monteiro-Filho, L.A. (2000). Fruit occurrence in the diet of the Neotropical otter, Lontra longicaudis in southern Brazilian Atlantic forest and its implication for seed dispersion. Mastozoología Neotropical, 7:33-36

Quadros, J., Monteiro-Filho, E.L.A. (2001). Diet of the neotropical otter, Lontra longicaudis, in Atlantic Forest area, Santa Catarina State, Southern Brazil. Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment, 36 (1): 15-21.

Quadros, J., Monteiro-Filho, E.L.A. (2002). Sprainting sites of the Neotropical otter, Lontra longicaudis, in an Atlantic Forest area of Southern Brazil. Mastozoologia Neotropical, 9 (1): 39-46.

Rheingantz, M.L., Trinca, C.S. (2015). Lontra longicaudis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T12304A21937379. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T12304A21937379.en.

Rodríguez-Mahecha, J., Alberico, M., Trujillo F., Jorgenson, J. (Eds). (2006). Libro rojo de los mamíferos de Colombia. Serie libros rojos de especies amenazadas de Colombia. Conservación Internacional Colombia & Ministerio de Ambiente, Viviendo y Desarrollo Territorial. Bogotá, Colombia. 433 pp.

Santos, L.B., Reis, N.R. (2012). Use of shelters and marking sites by Lontra longicaudis (Olfers, 1818) in lotic and semilotic environments. Biota Neotropica, 12 (1): 199-205 http://www.biotaneotropica.org.br/v12n1/en/abstract?article+bn02512012012

Santos, L.B., Dos Reis, N.R., Orsi Iheringia, M.L. (2012). Trophic ecology of Lontra longicaudis (Carnivora, Mustelidae) in lotic and semilotic environments in southeastern Brazil. Série Zoologia, 102 (3): 261-268.

Sierra-Huelsz, J.A., Vargas-Contreras, J.A. (2002). Registros notables de Lontra longicaudis annectens (Carnivora: Mustelidae) en el río Amacuzac en Morelos y Guerrero. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología 6:129-135

Trinca, C.S., Jaeger, C.F., Eizirik, E. (2013). Molecular ecology of the Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis): non-invasive sampling yields insights into local population dynamics. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 109: 932–948.

Trujillo, F., Gärtner, A., Caicedo, D., Diazgranados, M.C. (Eds.). (2013). Diagnóstico del estado de conocimiento y conservación de los mamíferos acuáticos en Colombia. Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible, Fundación Omacha, Conservación Internacional y WWF. Bogotá, 312 p. [In Spanish]

Waldemarin, H.F., Colares E.P. (2000). Utilisation of Resting Sites and Dens by the Neotropical River Otter (Lutra longicaudis) in the South of Rio Grande do Sul State, Southern Brazil. IUCN Otter Specialist Group Bulletin, 17 (1): 14 – 19.

Waldemarin, H.F. (2004). Ecologia da Lontra neotropical (Lontra longicaudis), no Trecho Inferior Da Bacia Do Rio Mambucaba, Angra Dos Reis. Tesis doctoral Universidade Do Estado Do Rio De Janeiro, Instituto De Biologia Roberto Alcântara Gomes, Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Biología Área De Concentração Em Ecología. [In Portuguese]

Wemmer, C., Kuns, T.H., Lundie-Jenkins, G., Mcshea, W.J. (1996). Mammalian sign. In: Wilson, D. E. Cole, F. R. Nichols, J. D. Rudan, R. Foster, M. S. (Eds). Measuring and monitoring biological diversity, standard methods for mammals. pp. 157-176. Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press.

Notes sur le Comportement de la Loutre à Longue Queue (Lontra longicaudis) sur la Rivière Palomino (La Guajira, Colombie)

La loutre à longue queue est un mammifère semi-aquatique qui a une large répartition géographique. Elle a l’habitude d’épreindre dans des zones visibles en dehors des plans d’eau ; ces indices de présence indirects sont au centre de la plupart des études les concernant, mais le comportement des espèces reste mal connu. En Colombie, l’espèce est considérée comme vulnérable et dans le nord du pays (La Guajira), aucune étude n’a été menée. Dans ce schéma, des observations sur le comportement de L. longicaudis dans la nature ont été répertoriées, en tant que première approche, tandis que des études d’occurrence ont été réalisées dans la région. Des observations ont été effectuées en 2015 pendant la saison sèche ou en l’absence de pluie (février), dans les cours moyen et inférieur de la rivière Palomino. Cinq sites de repérage ont été définis le long de la rivière avec une méthode d’observation par échantillonnage ad libitum. En conséquence, 31 comportements différents ont été observés, parmi lesquels l’immersion, la respiration après immersion, la nage superficielle et la recherche de nourriture qui ont obtenu le taux le plus élevé de fréquence, avec respectivement 16%, 15,6%, 12,8% et 10,7%.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Notas sobre el Comportamiento de Nutria Neotropical (Lontra Longicaudis) en el Río Palomino (La Guajira, Colombia)

La nutria neotropical es un mamífero semiacuático que ocupa una amplia distribución geográfica. Tiene el habito de defecar en áreas conspicuas fuera de los cuerpos de agua, por lo que este rastro indirecto es el foco de la mayoría de estudios sobre la especie, pero poco es conocido sobre su comportamiento. En Colombia es considerada Vulnerable y, en la zona norte del país (La Guajira), no se han realizado estudios. En este marco, se realizaron observaciones de comportamiento de L. longicaudisen vida silvestre, como una primera aproximación, mientras se llevaban a cabo estudios de presencia en el área. Las observaciones fueron realizadas en 2015 durante la estación seca o de no lluvias (febrero) en la parte media y baja del río Palomino. Cinco estaciones de observación fueron establecidas y se implementó el método de muestreo ad libitum.Como resultado, un total de 31 comportamientos diferentes fueron registrados, en los cuales inmersión, respirar tras la inmersión, nado y forrajeo tuvieron las frecuencias más altas con 16%, 15.6%, 12.8% y 10.7%, respectivamente.

Vuelva a la tapa