IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group Bulletin

©IUCN/SCC Otter Specialist Group

Volume 41 Issue 5 (December 2024)

Citation: Mahamoud, A., Hilmi, M., Ondiba, M., El Agbani, M.A. and Qninba, A. (2024). Maintenance of the Eurasian Otter Lutra lutra in a Section of the Beht River (Khémisset Province, Morocco) in the face of Human Activity. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 41 (5): 280 - 295

Maintenance of the Eurasian Otter Lutra lutra in a Section of the Beht River (Khémisset Province, Morocco) in the face of Human Activity.

Abdallah Mahamoud1*, Mohammed Hilmi1, Melvin Ondiba2, Mohammed Aziz El Agbani1, and Abdeljebbar Qninba1

1Laboratory of Geo-Biodiversity and Natural Heritage (GEOBIO), Scientific Institute, Mohammed V University in Rabat, Morocco

2Laboratory of Biodiversity, Ecology and Genome, Faculty of Sciences, Mohammed V University in Rabat, Morocco

*Corresponding Author Email: naderi@guilan.ac.ir

Received 15th June 2024, accepted 19th August 2024

Abstract: The Eurasian Otter Lutra lutra is one of the threatened carnivorous mammals in Morocco. It is listed as Near Threatened and Largely Depleted by the IUCN. From 2020 to 2024, we carried out seasonal monitoring of an otter population living in a section of the lower valley of the Beht River, which is heavily exploited for agriculture, livestock farming and the extraction of building materials (quarries), with the aim of assessing the species’ tolerance to the pressures and changes affecting its habitat. Monitoring has been carried out in almost all seasons during these four years, during which we have noted the pervasive presence of the species in the section, despite the challenges and sometimes extreme conditions it faces. Our observations show that in the short term, the Eurasian Otter can resist substantial changes in the environment caused by anthropogenic activity.

Keywords: Eurasian otter, Human activities, Beht River, Morocco

INTRODUCTION

The Eurasian Otter Lutra lutra has a Palearctic distribution and occurs in Europe, Asia and North Africa. It is a semi-aquatic mustelid (family Mustelidae) that feeds mainly on fish, amphibians and insects (Cusin, 2003). It is closely associated with aquatic environments, and particularly rivers. It is therefore an excellent indicator of the quality of these environments (Lemarchand, 2007).

The Eurasian Otter is classified as near-threatened (NT A2c) on the IUCN red list on a global scale (Loy et al., 2022) and “Vulnerable” in Morocco (Cuzin, 1996). Delibes et al. (2012) reported in their studies that the species was observed to be absent from intensely populated and cultivated flat areas and experienced a decline in the Atlantic plains in Morocco.

In Morocco, there have been significant alterations to the hydrographic systems, particularly in the lowlands and plains. The water quality and the hydrological conditions in Moroccan rivers have been significantly changed due to prolonged drought, excessive pumping, increased use of pesticides and fertilizers, and increased damming with lack of environmental flow. These transformations have led to long periods of hydrological drought, leaving the river beds completely dry for considerable distances (Libois et al., 2012). Conversely, water pollution negatively affects the presence and the quality of the Eurasian Otter’s prey, namely fish.

From February 2020 to February 2024, we conducted seasonal monitoring of a population of otters in a section of the lower valley of the Beht river, heavily exploited by humans for agriculture, livestock and farming, and extraction of construction materials (quarries), in order to assess the tolerance of the species to anthropogenic pressure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Area

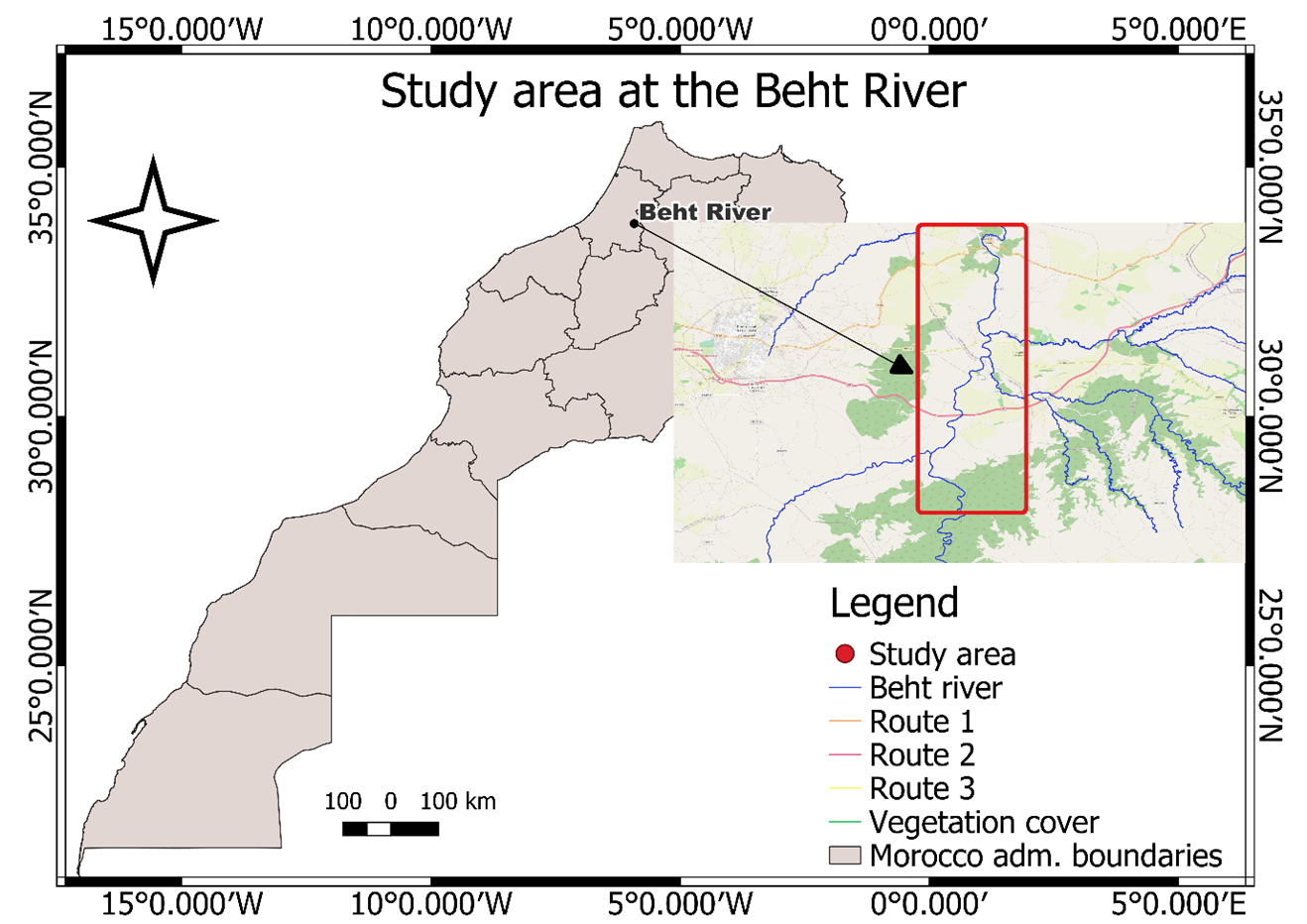

The study was carried out in the Beht River, one of the principal rivers of the Atlantic plains of Morocco. The Beht river flows through a diverse range of landscapes, encompassing plains and mountainous areas. The Beht begins its course in the western edge of the Middle Atlas Causse, and drains the northern edge of Central Morocco (Laabidi et al., 2016).

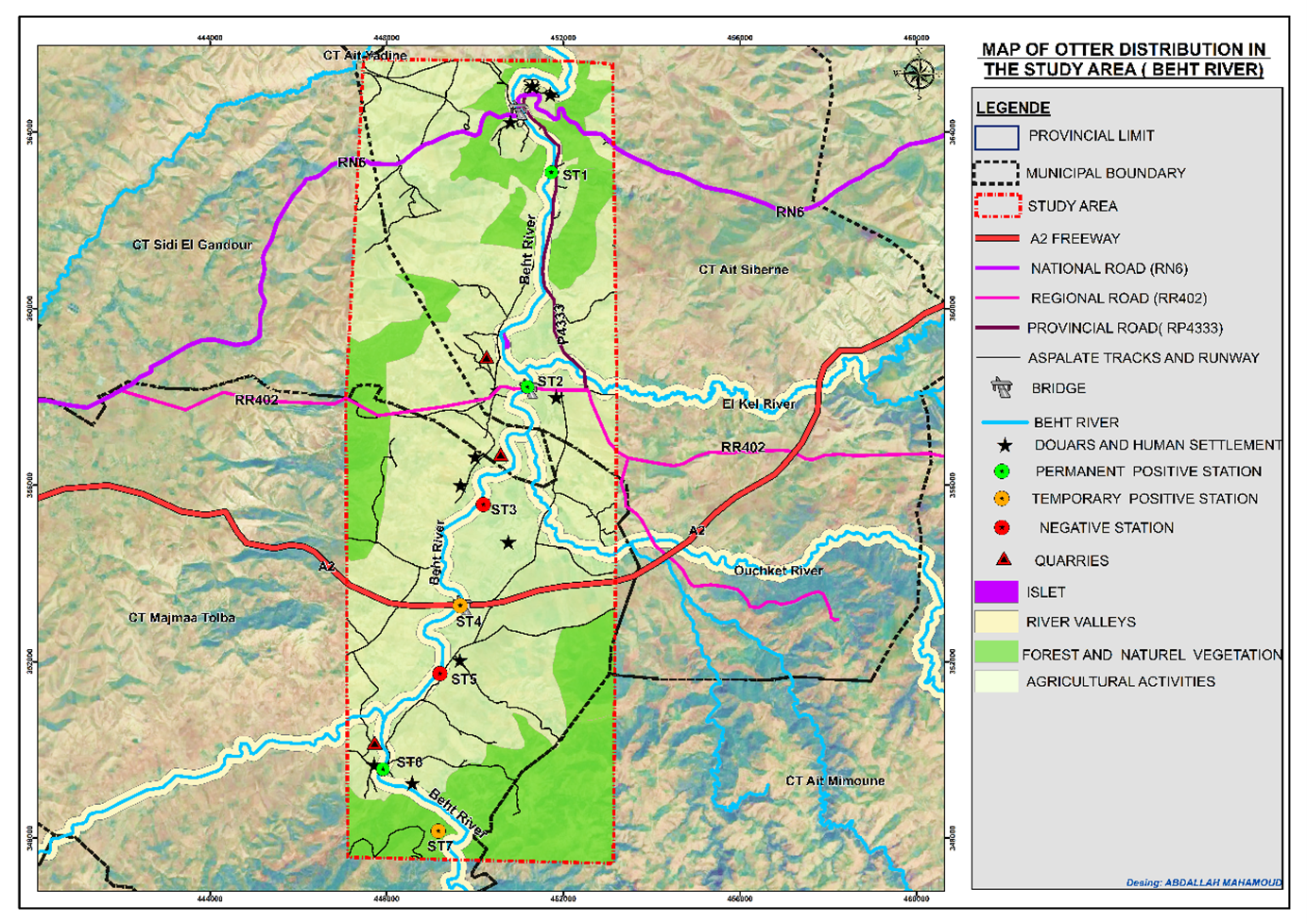

The study area is located in the north-east of the province of Khémisset in Morocco. It extends between the geographical coordinates 33°51'14.1"N - 5°55'26.3"W downstream to 33°44'00.4"N - 5°56'28"W upstream, and stretches for a distance of 25 kilometres. The altitude in the study area varies between 145 m and 152 m (Fig. 1).

The monitored stretch of the river hosts different species of fish that are consumed by the otter, like Carasobarbus fritschii, Lusciobarbus maghrebensis, Lepomis microlophus, Oreochromis niloticus, and some unidentified carps (Hilmi et al., 2023). The study area also hosts a population of the freshwater crab Potamon algeriense (Hilmi et al., 2023), which has been found to be consumed by the Eurasian Otter in the study area (Mahamoud et al., 2024).

Methods

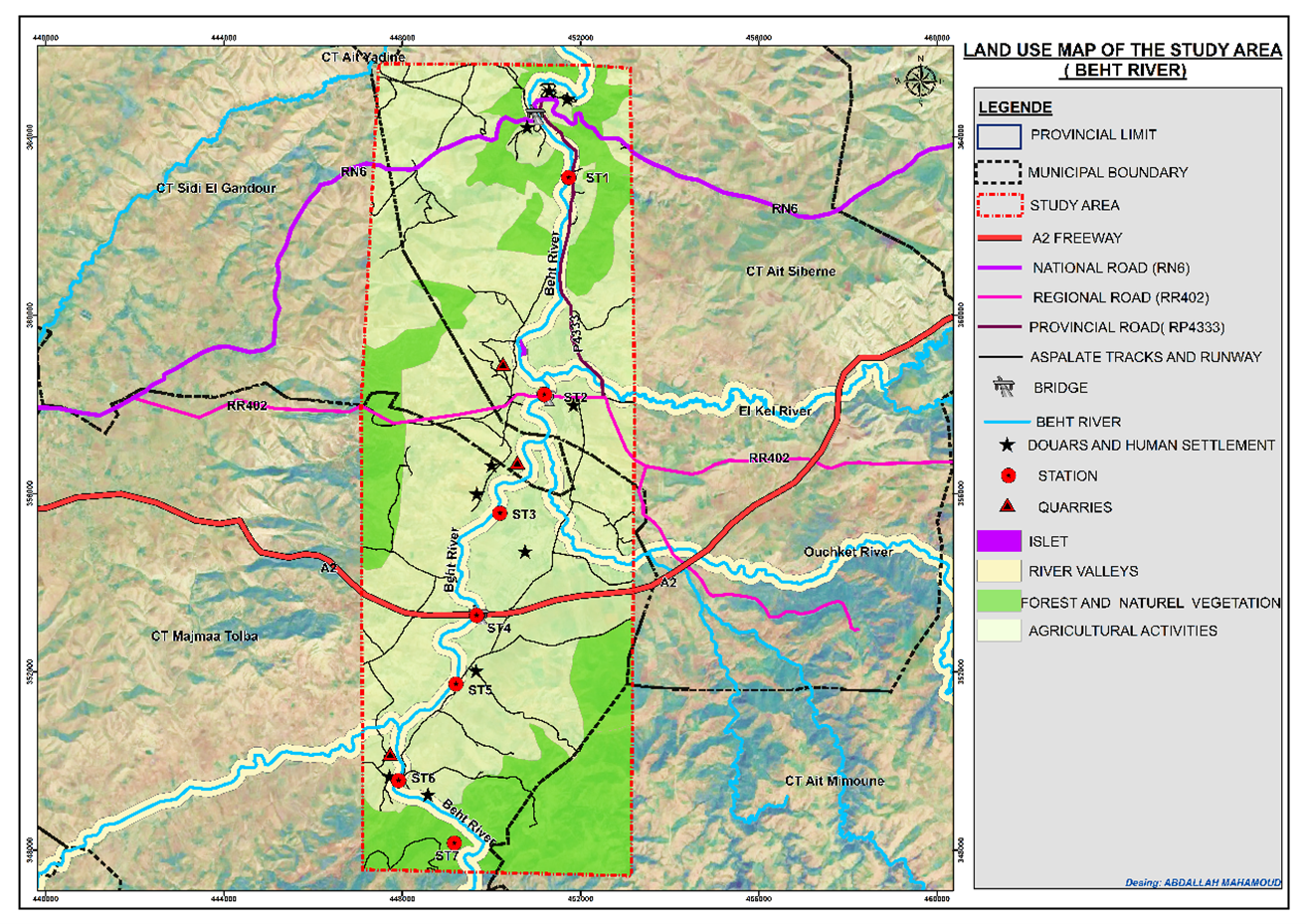

Development of the Land Use Map

A land use map was developed for the study area using ArcGIS software version 10.8 and visual observations carried out in the field.

Search for Signs of the Presence of the Otter

Due to the otter’s extreme discretion and distrust, the detection of its presence and the assessment of its distribution can only be achieved effectively by looking for presence clues in its environment (faeces and footprints). Indeed, the species is very difficult to observe directly, yet it leaves clear and distinctive marks that are relatively easy to spot.

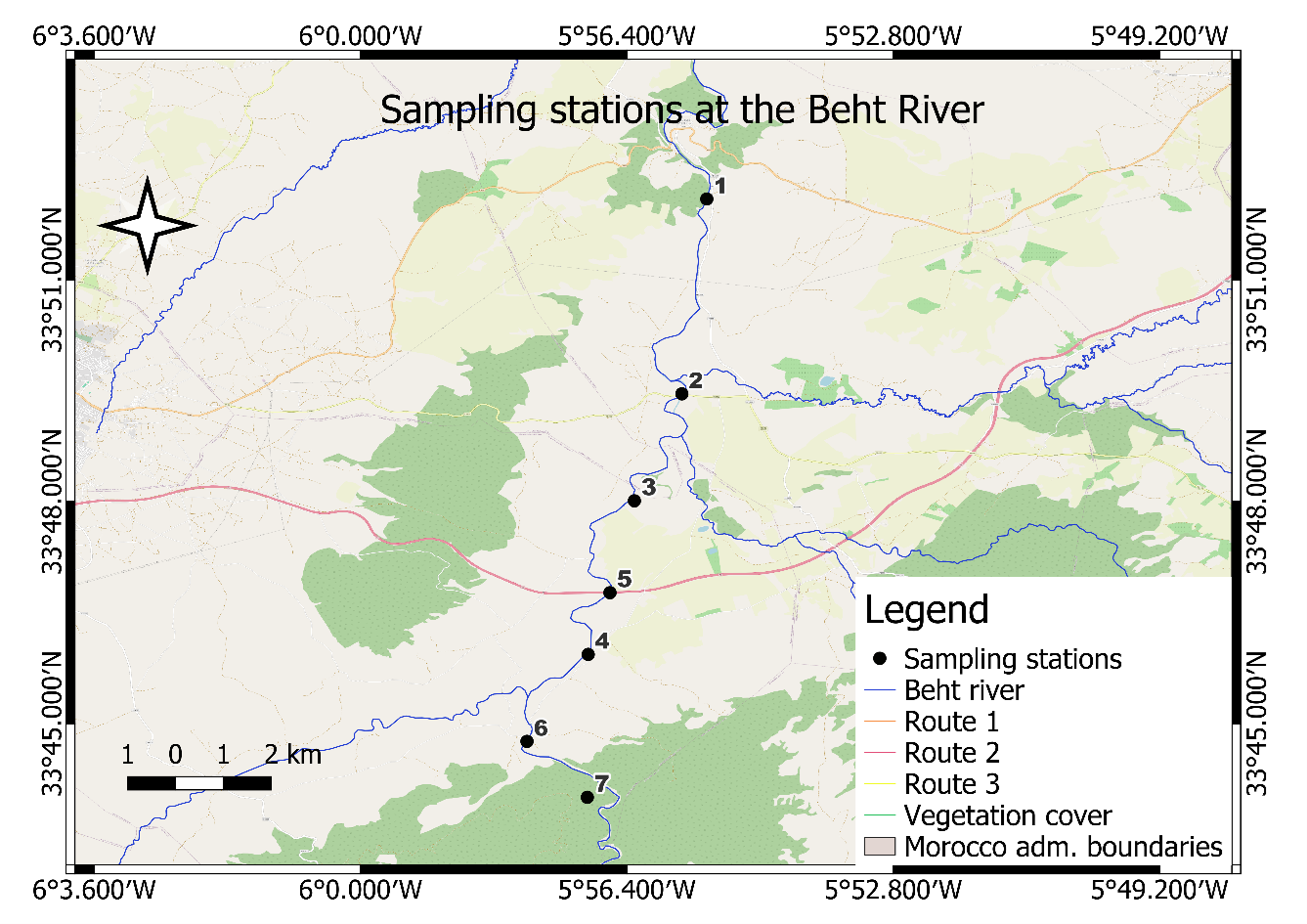

The initial selection of monitoring stations was made on the basis of their location along the section, with a spacing of 2.5 to 5 kilometers between them. The selection was based on the identification of locations that provide optimal habitat for the otter. This included areas with sufficient water depth, the presence of suitable shelter along the banks, and other factors conducive to presence of otters (Reuther et al., 2000; Richard-Mazet, 2005) (Fig. 2).

Research missions and presence index surveys were carried out from February 2020 to February 2024 with a frequency of one to nine missions per season, except for spring season in 2020 (due to the COVID19 pandemic). Mission durations varied from one to three days.

The surveys were carried out in the seven chosen stations in accordance with the IUCN survey protocol (Reuther et al., 2000), adapted to the context of the chosen study area. The protocol suggests searching by foot, on each of the study stations previously defined and distributed within the study area, for the most reliable indices of the Eurasian Otter’s presence, namely spraints (faeces) and imprints (paw marks) (Bouchardy et al., 2008) on 300 meters on either side of the reference point, on both banks when possible (Varanguin and Sirugue, 2008). A minimum of one visit was conducted at each station during each season, with the exception of spring 2020, during which surveys were not carried out at stations 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7. Additionally, surveys were not conducted at station 7 during the years 2023 and 2024. Some stations were surveyed on more than one occasion, given their potential for the species to become established (see Table 1). The signs of presence found were photographed as well as the surrounding environment; then, the spraints (faeces) were collected in freezer bags and transported to the laboratory for further analysis.

Use of Camera Trap

Camera traps (Browning Trial Cameras model BTC-8A) were set throughout the night during certain missions at the stations where we had detected the most signs of presence to try to observe the animal in activity and visually confirm the presence of the species. The parameters of the camera traps were set based on the study of Wright, 2023; the camera settings were set to image (12 MP), where 3 images were taken after the camera detected movement. An interval of one second was set between each image.

Station Characterisation

A detailed description of the environment was recorded at stations. The following environmental variables were considered:

- The riparian zone, with a description of the presence or absence of refuges and shelters.

- The presence or absence of water permeability.

- Average depth

- Dam releases

- The presence of gueltas (natural pools of water in the watercourse)

- The presence of large boulders in the bed of the river or on the bank.

- The presence/absence of human activities in the vicinity of the river (agriculture, quarrying, etc.) or artificial structures (bridges and culverts).

Analysis of Similarity between Stations.

A hierarchical ascending classification was employed to compare the presence of species indicators between stations within the study area. This statistical analysis was conducted using the PRIMER software package (Plymouth Routines in Multivariate Ecological Research).

DISTLM Analysis

A DISTLM (Distance-Based Linear Modelling) analysis was employed to evaluate the impact of the diverse environmental parameters observed in the field on the variability observed in the presence and absence of indices at the stations (Anderson and Mcardle, 2001).Sequential tests were utilised to ascertain which combinations of environmental variables most effectively explained the variability in presence (Legendre and Anderson, 1999).

RESULTS

Land Use Mapping of the Study Area

Using ArcGIS 10.8 software, we mapped land use based on field observations we made in the field (Fig. 3). The map shows that both sides of almost the entire section is devoted to agriculture. Harmful agricultural practices in the study area that affect the river’s hydrology and riparian habitats include excessive pumping from the river to irrigate crops, and bulldozing riverbanks (and associated plant cover) to acquire more agricultural land (Hilmi et al., 2024). In addition to agriculture, local people practice extensive livestock farming on both banks of the river throughout the study area.

The map also shows human settlements in and around the study area. We note the presence of quarries for the extraction of construction materials. Aggregate mining companies extract their materials directly from the bed of the river (Libois et al., 2012).

At both ends of the study area, there are also remnants of natural vegetation.

Distribution of the Otter in the Study Area

The table below provides a detailed account of the number of visits made to each station per season and per year.

Several signs of otter presence were observed in the study area in all of our visits over the four years. Fresh and/or dry tracks were the most frequently observed, even during the summer, which is characterised by prolonged drought of certain parts of the river (Fig. 4). On the other hand, Eurasian Otter tracks were mainly observed on the exposed muddy riverbed during the rainy seasons, especially in

autumn and winter, and during periods when the riverbed was well filled (Figure 5).

The examination of Station 7 yielded positive results during the spring, winter, and autumn seasons of the first two years. However, it was not explored in the final two years due to access difficulties. It is at stations 1, 2, and 6 that we noted the most otter sign during all four seasons of each year. Station 4 was only positive when water was present: during periods of drought, the water flow at this station ceased, especially during the summer seasons (Table 2, Fig. 6).

Only a single footprint was ever seen at station 3. Station 5, in contrast, never exhibited the slightest indication of the presence of the otter (Table 2). Based on these results, a distribution map of the species in the study area was constructed (Fig. 7).

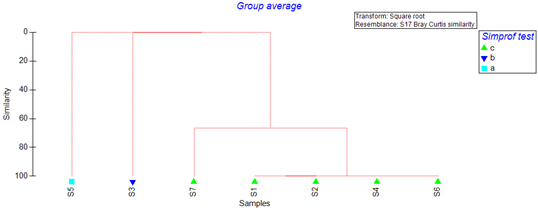

The dendrogram (Fig. 8) obtained by hierarchical ascending classification (HAC) analysis, combined with a SIMPROF test, applied to otter presence/absence data at seven stations, revealed a main group (C) comprising stations S1, S2, S4, S6 and S7, while isolating two stations (S3 and S5) from the four years of index research carried out. Within group C, stations S1, S2, S4 and S6 are 100% similar, while station S7 is 66.67% similar. On the other hand, the two isolated stations (S3 and S5) share no similarity either with each other or with the other stations.

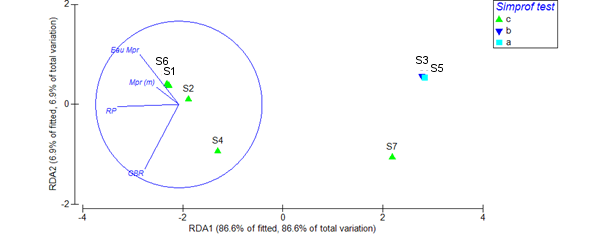

The non-parametric distance-based linear regression (DISTLM) analysis of the influence of environmental variables on otter presence (Fig. 9) indicates that, considering all 7 stations over the four years, there is a significant correlation between the presence of otter signs and 4 environmental parameters. The data analysis identified several environmental variables influencing the presence of the Eurasian otter. Dense riparian vegetation had an influence of 84.5% (Pseudo-F=27.281; P=0.035), Average depth (Mpr) 76.7% (Pseudo-F = 7.6246; p = 0.051), water permanence (Water Mpr) 60.4% (Pseudo-F=16. 495; P=0.007) and the presence of large boulders in the bed or on the banks (GBR) 54.9% (Pseudo-F=6.1032; P=0.049). These results show that otters are highly dependent on the presence of dense riparian vegetation and permanent water, as well as on the presence of large boulders in the river.

The non-parametric distance-based linear regression (DISTLM) analysis of the influence of environmental variables on otter presence (Fig. 9) indicates that, considering all 7 stations over the four years, there is a significant correlation between the presence of otter signs and 4 environmental parameters. The data analysis identified several environmental variables influencing the presence of the Eurasian otter. Dense riparian vegetation had an influence of 84.5% (Pseudo-F=27.281; P=0.035), Average depth (Mpr) 76.7% (Pseudo-F = 7.6246; p = 0.051), water permanence (Water Mpr) 60.4% (Pseudo-F=16. 495; P=0.007) and the presence of large boulders in the bed or on the banks (GBR) 54.9% (Pseudo-F=6.1032; P=0.049). These results show that otters are highly dependent on the presence of dense riparian vegetation and permanent water, as well as on the presence of large boulders in the river.

In 2020 and 2024, camera traps set overnight captured specimens. One individual was probably female, given its small size (Fig. 10), and was observed walking up the river on the bank downstream of station 2. Another individual was probably male given its large size, and was observed swimming upstream of the station 6 culvert pipe (Fig. 11).

DISCUSSION

Our results show that the Eurasian Otter permanently resides in the studied section of Beht river, even though some stretches completely dry up during the summer. Footprints were often only observed on mud during winter seasons and periods when the water level was high. Photos were taken by camera traps the first year and the last year, which reinforced the certainty of the permanent presence of the species in the study area.

The study was carried out over a 25 km stretch of river. The distribution patterns observed during the surveys reveal the presence of at least three individuals in the area, including one male (identified by a photo showing a large individual) and two females (photos of smaller individuals, taken downstream). The home ranges of these individuals appear to overlap, as an intermediate area between downstream and upstream shows little evidence. This could indicate that one female occupies the area downstream of station 4, while another is upstream.

The detection of indices of the species’ presence at the various selected stations revealed notable variations. In all instances, and throughout the whole course of our surveys, stations 1, 2 and 6 consistently yielded positive results, whether in the form of footprints, imprints or prey remains. The consistent occurrence of otters at these stations can be attributed to the sustained presence of conditions that are conducive to their survival. Indeed, at these three stations, water was consistently present, although at variable flow rates throughout the year, providing a habitat supporting the presence of fish, which constituted the primary food source for the otter. Furthermore, the discontinuous riparian plant cover along the watercourse provides the otter with shelter and refuge, enabling it to maintain its discretion and stealth qualities. The presence of artificial structures, which create refuge areas for fish populations (Simonnet and Gremillet, 2009) also contributed to the availability of food for the otter.

The presence of large boulders enabled individuals to mark their territory in a conspicuous manner. These observations are consistent with the findings of Lafontaine and de Alencastro (2002), who demonstrated that the presence or absence of the otter is influenced by a multitude of factors, including the availability of fish, the nature of the banks, and the quality of water. Furthermore, Reuther et al. (2000) point out that otters use their spraints on obstacles to demarcate their territory. The present study is distinguished from previous research in that it considers the impact of human activities on the persistence of the species in question, despite the presence of serious disturbances such as excessive water pumping, quarrying, and damming without implementing environmental flow.

Conversely, at stations 3 and 5, water was not a constant feature; for instance, the stream flow ceased entirely during the summer months. Furthermore, the banks were largely devoid of vegetation, providing minimal refuge for the species. The absence of permanent water, coupled with the lack of water pools in the vicinity of these stations, does not foster favourable conditions for the presence of the otter, as indicated by the findings of Simonnet and Gremillet (2009). Additionally, intensive human activities such as agriculture (Libois et al., 2012) exert a detrimental impact on the species’ presence.

Station 7 was not surveyed in any of the four years due to access difficulties but, as with Station 4, conditions are favourable for the presence of otters subject to the presence of water. Water is temporarily present at these stations, especially during the wetter seasons or during large releases from the Ouljet Essoltane dam upstream of the study area. This suggests that the otter is strongly tied to its environment; when it encounters unfavourable conditions it may migrate to survive but always returns to its original habitat when conditions improve.

In Morocco, according to Broyer et al. (1988), a large rural population is located wherever water is easy to access, especially along the edges of most rivers. Traditional pastoral practices, particularly strong in the mountains, contrasts with the intensive agriculture which affects all the northern plains (Broyer et al., 1988). This is true and clearly visible in our study area, as it is almost entirely exploited for agriculture, which in turn affects the river by excessive and direct pumping for irrigation.

The works of Aulagnier et al. (2015); Delibes et al. (2012); Étienne (2005) and Kruuk (2013) show that this species tends to desert heavily deforested, populated and intensively cultivated rural areas where river banks had little or no vegetation. It is also threatened by excessive use of water and possibly by pollution.

A study on the evolution of the distribution of the species in Morocco (Libois et al., 2012) has demonstrated that the drying up of wadi beds may potentially constitute a significant ecological barrier for the otter. This could result in the partitioning and isolation of mountain and lowland populations over time, with detrimental consequences for genetic variability. We observed that the otter exhibits considerable behavioural plasticity in response to the various pressures it encounters, including water scarcity and habitat disruption due to drought, and the non-compliance with the environmental requirements of dams, as evidenced by the Ouljet Essoltane dam, situated upstream of the study area. Additionally, human activities such as intensive agriculture, extensive livestock farming, and the extraction of building materials, with all the associated disturbances, also exert a considerable impact. This demonstrates that the species in question is capable of tolerating extreme conditions to a certain extent, provided that its fundamental needs are not entirely negated.

From upstream to downstream of the study area, there are human settlements on either side of the banks, including douars (villages), hamlets, and farmhouses; an important human presence which does not seem to cause the ottersto avoid an area.

Our observations confirm those of Cuzín (2003) who showed that the species is very frequently observed near irrigated crops and proves that its cohabitation with humans, in highly anthropized environments, is possible. These results also match those of Étienne (2005), Kuhn and Jacques (2011), Simonnet and Gremillet (2009), Sordello (2012) which showed that the otter demonstrates a capacity to occupy habitats co-inhabited by humans, particularly during its phases of colonization of new territories. This phenomenon is manifested in this species by its ability to cross human-occupied at night without being detected, or even to establish its presence in the immediate vicinity of intense human activities, subject to finding adequate food resources as well as places suitable for shelter.

We focused on the presence/absence of indices, which did not allow us to evaluate the density of the otter population in the study area. Otters have fairly large home ranges that can overlap (Étienne, 2005, Kuhn and Jacques, 2011), despite being territorial animals that mark their territories by depositing spraints in specific areas of the home range (Étienne, 2005).

These results demonstrate a permanent presence of otters in the river section despite the challenges it faces, namely the temporary drying out of certain parts of the river and anthropogenic activities. This study highlights the fidelity of the Eurasian Otter to its natural habitat and its remarkable capacity to adapt to various environmental challenges. Our research demonstrates that this species can tolerate extreme conditions, and that human presence does not necessarily seem to lead to its disappearance. It is possible for the otter to coexist with humans while retaining its natural discretion.

CONCLUSION

Our work shows that, despite the challenges it faces, especially the absence of water over long periods, the otter demonstrates consistent fidelity to its territory, and adapts to extreme conditions. Our observations show the ability of the Eurasian Otter to adapt but also underline the importance of taking into account the ecological needs of the otter in the management and conservation of its habitat, in order to ensure cohabitation between this species and humanity.

Acknowledgments - We express our gratitude to the Potasse de Khémisset company for its financial support for our field work and the purchase of equipment for our study, as part of their scientific cooperation with the Scientific Institute (Mohammed V University of Rabat). We would like to express our gratitude to the residents of Oued Beht for their cooperation, their valuable advice and their generosity. We also extend our thanks to all those who contributed to the production of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

Anderson, M. J., and Mcardle, B. H. (2001). Fitting multivariate models to community data : A comment on distance-based redundancy analysis. Ecology, 82(1), 290‑297. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[0290:FMMTCD]2.0.CO;2

Aulagnier, S., Bayed, A., Cuzin, F., and Thévenot, M. (2015). Mammals of Morocco: extinctions and declines during the XX the century. Travaux de l’Institut Scientifique, Série Générale, 8: 53-67. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309122190

Bouchardy, C., Boulade, Y., and Lemarchand, C. (2008). Natura 2000 en Auvergne. Connaître et gérer le patrimoine pour le bien-être des hommes. DIREN Auvergne – Catiche Productions 96p. https://side.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/CENT/doc/SYRACUSE/176981/natura-2000-en-auvergne-connaitre-et-gerer-le-patrimoine-naturel-pour-le-bien-etre-des-hommes?_lg=fr-FR

Broyer, J., Aulagnier, S., and Destre, R. (1988). La loutre Lutra lutra angustifrons Lataste, 1885 au Maroc. Mammalia, 52(3). https://doi.org/10.1515/mamm-1988-0306

Cusin.F, (2003). Les grands mammiferes du Maroc meridional (Haut Atlas, Anti Atlas et Sahara) : Distribution, écologie et conservation. 347P 182-189. https://theses.fr/2003MON2A001

Cuzin F., (1996). Répartition actuelle et statut des grands Mammifères sauvages du Maroc (Primates, Carnivores, Artiodactyles).Mammalia. 60(1), 101‑124. https://doi.org/10.1515/mamm.1996.60.1.101

Delibes, M., Calzada, J., Clavero, M., Fernández, N., Gutiérrez-Expósito, C., Revilla, E., & Roman, J. (2012). The Near Threatened Eurasian otter Lutra lutra in Morocco: No sign of recovery. Oryx, 46. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605311001517

Étienne P. (2005). La Loutre d’Europe – Description, répartition, habitat, moeurs, observation. Editions Delachaux & Niestlé. Collection Les sentiers du naturaliste. Paris. 192p. ISBN: 978-2603014608

Haring, C., Weier, S. and Linden, B. (2023). Distribution and Habitat Preference of Cape Clawless Otters (Aonyx capensis) and Water Mongooses (Atilax paludinosus) in the Soutpansberg, South Africa. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 40 (1) : 26—38. https://www.iucnosgbull.org/Volume40/Haring_et_al_2023.html

Hilmi, M., Mahamoud, A., El, M., and Qninba, A. (2023). Biodiversity and ecological values of a part of the lower valley of Oued Beht located between the dams of El Kansera and Ouljet Essoltane (Province of Khemisset – Morocco). Bulletin de l’Institut Scientifique, Rabat, Section Sciences de la Vie, 44: 7‑17. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372159390

Hilmi, M., Mahamoud, A., Taouali, O., Mhammdi, N., Fernandes, P., Agbani, M. A. E., and Qninba, A. (2024). Nesting habitat of the Brown-throated Martin Riparia paludicola mauritanica in Morocco. Ostrich. Journal of African Ornithology, 95(1), 10 - 20. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ostrich/article/view/269995

Kruuk H. (2013). Lutra lutra Common otter. In : J. Kingdon J. & M. Hoffmann (eds). Mammals of Africa. Carnivores, pangolins, equids ans rhinoceroses. Bloomsbury Publ., London,. Volume V, 111‑113. ISBN : 9781399420358

Kuhn R., & Jacques H. (2011). La Loutre d’Europe Lutra lutra (Linnaeus, 1758). Encyclopédie des carnivores. Société française pour l’étude et la protection des mammifères (SFEPM).Fascicule 8. 72. ISBN : 978-2905216434

Laabidi, A., El Hmaidi, A., Gourari, L., & El Abassi, M. (2016). Apports Du Modele Numerique De Terrain Mnt A La Modelisation Du Relief Et Des Caracteristiques Physiques Du Bassin Versant Du Moyen Beht En Amont Du Barrage El Kansera (Sillon Sud Rifain, Maroc) Lahcen Gourari, PES. European Scientific Journal, 12, 1857‑7881. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2016.v12n29p258

Lafontaine, L., and de Alencastro, L. (2002). Statut de la loutre d’Europe (Lutra lutra) et contamination des poissons par les polychlorobiphényles (PCBs) : Éléments de synthèse et perspectives. L’étude et la conservation des carnivores, 113‑119. https://infoscience.epfl.ch/handle/20.500.14299/214884

Legendre, P., and Anderson, M. J. (1999). Distance-based redundancy analysis: Testing multispecies responses in multifactorial ecological experiments. Ecological Mongraphs, 69(1): 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9615(1999)069[0001:DBRATM]2.0.CO;2

Lemarchand, C. (2007). Etude de l’habitat de la loutre d’Europe (Lutra lutra) en région Auvergne (France) : Relations entre le régime alimentaire et la dynamique de composés essentiels et d’éléments toxiques. These de doctorat, Clermont-Ferrand 2. https://www.theses.fr/2007CLF21746

Libois, R., Rosoux, R., and Fareh, M. (2012). Evolution de la répartition de la loutre d’Europe (Lutra lutra) au Maroc. https://hdl.handle.net/2268/125633

Loy, A., Kranz, A., Oleynikov, A., Roos, A., Savage, M. and Duplaix, N. (2022). Lutra lutra (amended version of 2021 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. e.T12419A218069689. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-2.RLTS.T12419A218069689.en

Mahamoud, A., Hilmi, M., Ondiba, M., El Agbani, M.A., and Qninba, A. (2024). Freshwater Crab (Potamon algeriense) in the Diet of the Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra) in the Lower Valley of Beht River in Morocco. IUCN Otter Spec. Group Bull. 41 (2): 115 - 123.

Reuther, C., Dolch, D., Green, R., Jahrl, J., Jefferies, D., Krekemeyer, A., Kucerova, M., Madsen, A. B., Romanowski, J., & Roche, K. (2000). Habitat: Surveying and monitoring distribution and population trends of the Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra). GN-Gruppe Naturschutz GmbH Sudendorffallee, 1. https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/7962

Richard-Mazet, A. (2005). Etude écotoxicologique et environnementale de la rivière Drôme : Application à la survie de la loutre. PhD Thesis, Sciences du Vivant [q-bio]. Université Joseph-Fourier - Grenoble I. https://theses.hal.science/tel-00275129

Simonnet, F., and Gremillet X. (2009). Préservation de la Loutre d’Europe en Bretagne : Prise en compte de l’espèce dans la gestion de ses habitats. Le Courrier de la nature. 247: 25‑33. https://bretagne-environnement.fr/notice-documentaire/preservation-loutre-europe-bretagne-prise-compte-espece-gestion-ses-habitats

Sordello R. (2012). Synthèse bibliographique sur les traits de vie de la Loutre d’Europe (Lutra lutra) (Linnaeus, 1758)) relatifs à ses déplacements et à ses besoins de continuités écologiques. Service du patrimoine naturel du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle. Paris. 19p. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/276275804

Varanguin.N, & Sirugue.D. (2008). Vers une reconquête des rivières par la Loutre en Bourgogne. Bourgogne-Nature, 8: 205‑227. https://observatoire.shna-ofab.fr/fichiers/bn-8-pages-205-227-web_1397745386.pdf

Résumé: Maintien De La Loutre d’Europe Lutra lutra dans un Secteur de l’Oued Beht (Province de Khémisset Maroc) face à des Activites Anthropiques

La Loutre d’Europe Lutra lutra fait partie des mammifères carnivores de la faune sauvage dulçaquicole du Maroc et elle est inscrite dans la liste rouge de l’IUCN. De 2020 à 2024, nous avons effectué un suivi saisonnier d’une population de Loutre présente dans un tronçon de la basse vallée du cours principal de l’Oued Beht fortement exploité par l’homme pour l’agriculture, l’élevage et l’extraction des matériaux de construction (carrières) dans le but d’évaluer la tolérance de l’espèce face aux pressions et aux changements que subit son habitat. Des missions de suivi ont été réalisées dans la quasi-totalité des quatre saisons pendant ces quatre années au cours desquelles nous avons noté une présence permanente de l’espèce dans l’aire d’étude malgré les défis et parfois les conditions extrêmes auxquelles elle est confrontée. De plus la présence humaine ne semble pas nécessairement entraîner la disparition de l’espèce qui continue de cohabiter avec l’homme tout en conservant sa discrétion naturelle.

Revenez au dessus

Resumen: Mantenimiento de la Nutria Europea Lutra lutra en una Sección del Río Beht (Provincia de Khémisset, Marruecos) de Cara a la Actividad Humana

La nutria Europea (Lutra lutra) es uno de los mamíferos carnívoros que forman parte de la fauna silvestre de agua dulce de Marruecos, y está incluida en la Lista Roja de UICN. Entre 2020 y 2024 llevamos a cabo el monitoreo estacional de una población de nutrias que vive en una sección del valle inferior del cauce principal del Río Beht, que está intensamente explotado por el ser humano para agricultura, ganadería y extracción de materiales para construcción (canteras), con el objetivo de evaluar la tolerancia de la especie a las presiones y cambios que afectan su hábitat. El monitoreo se llevó a cabo durante las cuatro (4) estaciones del año durante éstos 4 años -cubriendo casi todas las estaciones. Hemos notado una extendida presencia de la especie en ésta sección de río, a pesar de las condiciones desafiantes y a veces extremas. Es más, la presencia del ser humano no necesariamente parece causar que la especie desaparezca o se desplace, en lugar de ello parece mantener una co-habitación con el hombre, aunque mantenniendo su natural discreción.

Vuelva a la tapa

ص

استمرار تواجد القضاعة الأوراسية في جزء من وادي بهت (إقليم الخميسات المغرب) أمام الضغط الكبير للأنشطة البشرية

القضاعة الأوراسية هي أحد الثدييات آكلة اللحوم المهددة بالانقراض في المغرب. وقد أدرجها الاتحاد الدولي لحفظ الطبيعة والموارد الطبيعية على قائمة الحيوانات القريبة من خطر الانقراض. في الفترة من 2020 إلى 2024، أجرينا مراقبة موسمية لمجموعة من القضاعات الأوراسية التي تعيش في الجزء السفلي لوادي بهت، الذي يعرف استغلالا بشريا كبيرا يتمثل خاصة في الفلاحة واستخراج مواد البناء (المقالع)، بهدف تقييم مدى تحمل القضاعة للضغوط والتغيرات التي تؤثر على موائلها. تم إجراء الرصد تقريبا في جميع فصول هذه السنوات الأربع، حيث لاحظنا خلالها انتشارا واسعا لهذا النوع في هذا الجزء من الوادي، على الرغم من التحديات والظروف القاسية التي يواجهها في بعض الأحيان. تظهر ملاحظاتنا أن القضاعة الأوراسية تستطيع على المدى القصير مقاومة تغيرات مهمة ناجمة عن النشاط البشري في بيئته.

العودة إلى البداية